Bastrop, Louisiana

| Bastrop, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

North entrance to Bastrop City Hall, designed by local architect Hugh G. Parker, Jr. | |

| Motto: The City of Spirit, Pride, and Progress | |

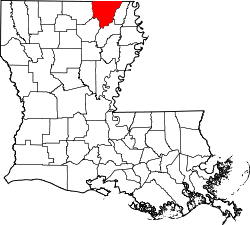

Location of Bastrop in Morehouse Parish, Louisiana. | |

.svg.png) Location of Louisiana in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 32°46′40″N 91°54′54″W / 32.77778°N 91.91500°WCoordinates: 32°46′40″N 91°54′54″W / 32.77778°N 91.91500°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Morehouse |

| City Charter | 1852 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor and Board of Aldermen/City Council |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 8.90 sq mi (23.04 km2) |

| • Land | 8.90 sq mi (23.04 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 167 ft (51 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 11,365 |

| • Estimate (2016)[2] | 10,578 |

| • Density | 1,189.07/sq mi (459.08/km2) |

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 71220 |

| Area code(s) | 318 |

| FIPS code | 22-04685 |

Bastrop is the largest city in and the parish seat of Morehouse Parish, Louisiana.[3] The population was 11,365 at the 2010 census, a decrease of 1,623 from the 12,988 tabulation of 2000. The population of Bastrop is 73 percent African American.[4] It is the principal city of and is included in the Bastrop, Louisiana Micropolitan Statistical Area, which is included in the Monroe-Bastrop, Louisiana Combined Statistical Area.

History

Bastrop was founded by the Baron de Bastrop (born Felipe Enrique Neri), a Dutch businessman accused as an embezzler. He had fled to the then Spanish colony of Louisiana to escape prosecution, and became involved in various land deals. In New Spain, he falsely claimed to be a nobleman. He received a large grant of land, provided that he could settle 450 families on it over the next several years. However, he was unable to do this, and so lost the grant. Afterwards, he moved to Texas, where he claimed to oppose the sale of Louisiana to the United States, and became a minor government official. He proved instrumental in Moses Austin's plan (and later, that of his son, Stephen F. Austin) to bring American colonists to what was then northern Mexico.

Bastrop formally incorporated in 1857, and is the commercial and industrial center of Morehouse Parish. In the 19th century, it was notable as the western edge of the great north Louisiana swamp, but more favorable terrain resulted in the antebellum rail line connecting to Monroe, Louisiana, further to the south.

Bastrop was a Confederate stronghold during the American Civil War until January 1865, when 3,000 cavalrymen led by Colonel E.D. Osband of the Third U.S. Colored Cavalry, embarked from Memphis, Tennessee, for northeastern Louisiana. Landing first in southeastern Arkansas, Osband and his men began foraging for supplies into Louisiana and established headquarters at Bastrop. They brought in a large number of horses, mules, and Negroes, according to the historian John D. Winters in The Civil War in Louisiana. When Osband learned that Confederate Colonel A.J. McNeill was camped near Oak Ridge in Morehouse Parish with 800 men, he sent a brigade into the area. The Union troops found fewer than 60 Confederates, most of whom fled into the swamps, leaving behind horses and mules.*[5]

During the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, Bastrop was the site of a relief camp for refugees. During World War II, it was the site of German prisoner-of-war camp.

Bastrop is also the parish seat of Morehouse Parish and is within an area marketed to tourists as the Sportsman's Paradise Region of Louisiana. It is a Main Street Community and has received Transportation Enhancement funding for improvements in its historic district.[6]

Celebrations and concerts are held in the historic downtown at the restored 1914 Morehouse Parish Courthouse and Rose Theater. Bastrop is home to the Snyder Museum and Creative Arts Center, housed in the circa 1929 home of a local family. Volunteers lead heritage appreciation tours for children and interpret the history of the parish using local artifacts.[6]

Economics

The Bastrop area economy is largely based on forestry, cotton and rice farming, and potato shipping. Hunting, camping, and fishing are pastimes in the many bayous and river. Shopping is also a popular tourist attraction in the area. The Snyder Museum keeps information relating to local history and displays furniture typical of fine homes from the Civil War and early 20th century periods.

Barham's Drugs on the courthouse square in Bastrop was formerly owned and operated by Henry Alfred Barham, Jr. (1919-1993), and his wife, the former Ann Jocelyn Heres (1929-2015). Mrs. Barham, originally educated in home economics at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, was the first woman pharmacist in Morehouse Parish and a graduate of the pharmacy school at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. She was a two-term member of the Morehouse Parish School Board.[7] Alfred Barham was an older brother of Mack Barham, a justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, and a distant cousin of State Senators Robert J. Barham and Edwards Barham. Both Alfred and Mack Barham had wives named "Ann".

IPC mill closing

On November 21, 2008, International Paper Company, the largest area employer, announced the cessation of operations of its Bastrop mill. The company first said that the closure is "indefinite" and subsequently confirmed that the exodus is "permanent".[8] At least 550 workers lost their jobs. Another two thousand employees in auxiliary businesses, some 17 percent of the area workforce, faced layoffs or downsizing. Clarence Hawkins, then the Bastrop mayor, predicted that the impact of the closure would be felt throughout northeastern Louisiana and southern Arkansas because employees and suppliers come from all over the region.[9]

Then Governor Bobby Jindal deployed a Louisiana Work Force Commission team to open an information center in Bastrop. Jindal indicated that he will pursue an economic transition plan for Morehouse Parish. The governor explained that the closure resulted because is "simply no market for [pulp] produced at this mill. I don't want to sugarcoat this. There would have to be a dramatic change in the world economy for it to reopen, and it would have to strengthen as quickly as it weakened." Jindal said the state offered "more direct assistance to International Paper than we have to any other company since I've been governor." The company, however, explained that the issue was no longer one of inducements to stay but the vanished market. The largest customer of the Louisiana mill was China, where orders ceased with international economic downturns and the tightening of credit markets.[10]

Poultry plant shutdowns affect Bastrop

Three months after the announcement of the International Paper mill closing, Pilgrim's Pride, a poultry company, confirmed the closure of operations in nearby Arcadia in Bienville Parish, Athens in Claiborne Parish, Choudrant in Lincoln Parish, and Farmerville in Union Parish. The closings will cost this section of mid-North Louisiana a combined 1,300 jobs.[11]

Robert C. Eisenstadt (born 1954), an economics professor at the University of Louisiana at Monroe, told The Shreveport Times that the closures, unlike previous exits of State Farm Insurance and International Paper, will have a disproportionate impact on lower-income workers: "This is our largest employer of low- to medium-skilled workers. In our area, there aren't a lot of good alternative opportunities for them and they don't have as many resources to leave the area for opportunity as did the workers at those other companies."[11]

Then Bastrop Mayor Clarence Hawkins estimated about five hundred, or nearly half of the Pilgrim's Pride processing plant workers in Farmerville commuted from Bastrop, many in vans running on a regular schedule.[11]

Meanwhile, Governor Jindal and the legislature, in a bid to save the jobs at stake, moved to subsidize with $50 million from the state's megafund the incoming owner of the poultry plant, Foster Farms of California.[12]

With Louisiana state assistance, Foster Farms did procure the former Pilgrim's Pride company, which also closed plants in Farmerville, Louisiana, and El Dorado, Arkansas. Foster Farms expected that when the plant reached full capacity, it would employ at least 1,100 persons with a corresponding annual payroll of more than $24 million.[13]

DG Foods based in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, opened a poultry processing plant at Bastrop to served the poultry industry in June 2011. The company currently employs around 380 workers and serve customers with custom processing of products and sized portions for retail sales and restaurants. The poultry industry continues to be an important employer for low to medium skilled workers.

Drax Biomass

On December 17, 2012, Governor Jindal and Drax Biomass International Inc. CEO Chuck Davis traveled to Morehouse Parish, Louisiana to announce plans to build a wood pellet facility in Bastrop and a storage-and-shipping facility at the Port of Greater Baton Rouge. The project was completed and the plant was commissioned in 2015 adding 79 new direct jobs, with 64 of the jobs located at the Bastrop wood pellet facility. LED estimates the project generated an additional 150 indirect jobs in the state. Drax' budget for the Morehouse mill was about $120 million. Drax says the average pay plus benefits averages more than $35,000 annually at the pellet mill. Drax is shipping wood pellets formed in Morehouse Parish to its U.K. Energy facilities for use in generating renewable power. July, 2013, Drax Biomass started work on clearing the area for the new wood-based pellet facility in Bastrop.[14] [15]

Top ten employers

1. Morehouse Parish School Board - 700 [16]

2. DG Foods - 380 [16]

3. Morehouse General Hospital - 250 [16]

4. Wal-Mart - 200 [16]

5. City of Bastrop - 175 [16]

6. Morehouse Parish Sheriff's Office - 145 [16]

7. Oakwood Home For the Elderly - 120 [16]

8. Lagniappe Rehab Hospital - 110 [16]

9. Cherry Ridge Guest Care LLC - 100 [16]

10. Legrand Health Care - 100 [16]

Geography

Bastrop is located at 32°46′40″N 91°54′54″W / 32.77778°N 91.91500°W (32.777855, −91.914944).[17] It is situated at the crossroads of U.S. Highway 425 and U.S. Highway 165. La. Highway 2 and Louisiana Highway 139 also runs through the town.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 8.9 square miles (23 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 481 | — | |

| 1870 | 521 | 8.3% | |

| 1880 | 822 | 57.8% | |

| 1900 | 787 | — | |

| 1910 | 854 | 8.5% | |

| 1920 | 1,216 | 42.4% | |

| 1930 | 5,121 | 321.1% | |

| 1940 | 6,626 | 29.4% | |

| 1950 | 12,769 | 92.7% | |

| 1960 | 15,193 | 19.0% | |

| 1970 | 14,713 | −3.2% | |

| 1980 | 15,527 | 5.5% | |

| 1990 | 13,916 | −10.4% | |

| 2000 | 12,988 | −6.7% | |

| 2010 | 11,365 | −12.5% | |

| Est. 2016 | 10,578 | [2] | −6.9% |

As of the 2010 census Bastrop had a population of 11,365. The racial makeup of the population was 65% African-American, 30 % White, 0.4% Asian, 0.1% NativeAmerican, 0.2% from some other race and 1.1% reporting more than one race. 0.8% of the population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.[19]

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 12,988 people, 4,723 households, and 3,301 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,543.9 people per square mile (596.3/km²). There were 5,292 housing units at an average density of 629.1 per square mile (243.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 34.67% White, 64.50% African American, 0.13% Native American, 0.15% Asian, 0.04% from other races, and 0.51% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.69% of the population.

There were 4,723 households out of which 33.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.0% were married couples living together, 28.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.1% were non-families. 27.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.25.

In the city, the population was spread out with 30.1% under the age of 18, 10.1% from 18 to 24, 25.6% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females there were 82.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $20,418, and the median income for a family was $26,250. Males had a median income of $30,477 versus $15,813 for females. The per capita income for the city was $10,769. About 29.6% of families and 35.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 46.2% of those under age 18 and 30.5% of those age 65 or over.

National Guard

1023rd Engineer Company (Vertical) of the 528th Engineer Battalion of the 225th Engineer Brigade is located in Bastrop.

Government

Bastrop is governed by a mayor and board of aldermen. In the nonpartisan blanket primary held on April 4, 2009, Betty Alford-Olive upset incumbent Mayor Clarence Hawkins. Alford-Olive polled 58 percent of the ballots. Her fellow Democrat Hawkins, received 29 percent, and a third candidate, Troy L. Downs, garnered the remaining 12 percent. Alford-Olive, who completed two terms on the city council, called her victory a sign that people want change in municipal government. "We hope to get small businesses to grow and involve the banking industry. We have to look at where the economy is emerging. We have to make sure we have a trained work force." Hawkins had been the first African-American to serve in the top municipal position in Bastrop history.[21]

In 2013, Arthur Jones, the former long-term Bastrop municipal recreation director, narrowly unseated Alford-Olive. In his first days on the job in July, he spent much of his time reopening the large East Madison swimming pool. The facility has a capacity of 450,000 gallons of water and can accommodate three hundred persons. Jones said that his interest in the pool is a reflection of his concern about idle youth. Jones will seek to attract new smaller industries to Bastrop to fill part of the void left by the closing in 2008 of the International Paper mill.[22]

J.D. DeBlieux, a former state senator from Baton Rouge who spent his later years in the Bastrop area, was among the first white politicians in Louisiana to support the civil rights agenda.

The Bastrop City Hall and Police Station were designed by native son Hugh G. Parker (1934–2007), who overcame childhood polio to become a significant architect in Louisiana. The original City Hall dates to 1927 under the Mayor A. G. Bride.

Media

Bastrop and Morehouse Parish are served by a daily newspaper, the Bastrop Daily Enterprise.

Education

School District

The Morehouse Parish School Board operates all public schools within the City of Bastrop and Morehouse Parish.

Elementary Schools

- Beekman Charter Elementary

- Delta Magnet Elementary

- Henry Victor Adams Elementary

- Pine Grove Elementary

- Westside Morehouse Magnet Elementary

Middle Schools

- Beekman Charter Junior High School

- Delta Magnet Junior High School

- Morehouse Junior High School

- Westside Morehouse Magnet Junior High School

High Schools

- Bastrop High School

- Beekman Charter High School

Alternative Schools

- Bastrop Learning Academy - an Alternative School for students that prepares them for Career and Workforce Training

Private Schools

- Prairie View Academy - the only Private School in Bastrop and Morehouse Parish serving grades PreK 3 through 12th Prairie View Academy

Public Libraries

The City of Bastrop is home to two public libraries. The Main Branch which is Morehouse Parish Library and Dunbar Library. Morehouse Parish Public Library System

Post Secondary Schools

Louisiana Delta Community College (Bastrop Campus & Bastrop Airport Campus) The City of Bastrop offers its citizens and parish with two campuses of its Region Community and Technical College System. The Main Branch is on Kammell St. and the other branch is on Airport Rd. adjacent to the City's and Parish Main Airport which is the Morehouse Memorial Airport. [23]

Colleges and Universities within a 65 mile radius

- University of Louisiana at Monroe(about 20 miles; Monroe, LA; FT enrollment: 8,526)[24]

- Louisiana Delta Community College (Main campus about 20 miles; Monroe, LA; FT enrollment: 2,587)[25]

- Career Technical College (about 20 miles; Monroe, LA; FT enrollment: 1,036)

- Northeast Louisiana Technical College Delta Ouachita Main Campus (about 23 miles; West Monroe, LA; FT enrollment: 1,536)

- Unitech Trainning Academy (about 23 miles; West Monroe, LA; FT enrollment: 115)

- Louisiana Tech University (about 60 miles; Ruston, LA; FT enrollment: 11,271)[26]

- Grambling State University (about 64 miles; Grambling, LA; FT enrollment: 4,504)[25]

- University of Arkansas at Monticello (about 57 miles; Monticello, AR; FT enrollment: 3,483)[25]

Bastrop High School Prayer Controversy

In 2011, graduating senior Damon Fowler objected to prayer at the Bastrop High School graduation exercises, claiming a looming violation of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.[27] The American Civil Liberties Union of Louisiana asked the school not to include a prayer in the May 20 graduation.[27] At the Thursday night rehearsal for the graduation, senior Sarah Barlow included a prayer that explicitly mentioned Jesus Christ, and during the graduation, student Laci Mattice led people in the Lord's Prayer before a moment of silence. The school says that Mattice was told not to include a prayer.[27] Fowler stated that after his objections became public he was ostracized by other students.[28]

Gallery

- Historic First United Methodist Church dates to 1826 in Bastrop; the current downtown sanctuary was completed in 1924.

- First Baptist Church of Bastrop

- The unusually configured First Church of God in Bastrop is located across the street from the Morehouse Parish Library.

- Rose Theatre at rear of the Morehouse Parish Courthouse.

- Farmers Market in Bastrop

- Central Fire Station in Bastrop

- Bastrop has two branches of Louisiana Technical College.

- Bastrop welcome sign

Neighborhoods

Park Place

White Star

Gladney Park Estates

Morehouse Country Club Estates

Morehouse Country Club Extension Estates

Ralph George Park Estates

Downtown

Austin Village

Naff Estates

South Point

Hill View

Emily Clark Park Estates

Everglade Estates

Arrowhead Estates

Airport Estates

Cleveland Estates

Space Estates

Cooperlake Estates

Marlett Estates

Uptown Estates

United Estates

Rusty Acres Estates

Cherry Ridge Estates

Madison Place

Sugar Hill

Suburbs

Wardville

Uscarco

Shelton

Rogers

Point Pleasant

Perryville

Newhlock

Log Cabin

Collinston

Gum Ridge

Marcarco

Spyker

Upland

Windsor

Oak Ridge

Bordenax

Mer Rouge

Galion

Stampley

Bonita

Haynes Landing

Jones

Laark

McGinty

New Land Grove Landing

Oak Landing

Beekman

Vaughn

Stevenson

Robinson

Naff

Humphreys

Gedddie

Couters Neck

Notable people

- Keith Babb, KNOE-TV personality prior to 1971; principal auctioneer of American Quarter Horse, reared in Bastrop

- Stephen A. Caldwell, Louisiana educator, was Morehouse Parish school superintendent from 1915 to 1922.

- Ronnie Coleman, professional bodybuilder

- Bill Dickey, Major League Baseball player

- Denzel Devall, College Football Player three-year starter for The University of Alabama at outside linebacker; part of two national championship teams (2012 & 2015); played from 2012-2015

- Stump Edington, Major League Baseball player who died in Bastrop

- David 'Bo' Ginn, state senator from Morehouse Parish from 1980 to 1988

- Luther E. Hall, Governor of Louisiana

- Sam Hanna, Sr., newspaper publisher began his journalism career at the Bastrop Daily Enterprise.

- Ed Head, Major League Baseball player who died in Bastrop.

- The Hemphills, Eight-time winning GMA Dove Award winners; founded former gospel music singing group in Bastrop in 1967[29]

- William Kennon Henderson, Jr., founder of radio station KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana, was born in Bastrop in 1880.[30]

- Mable John, Motown Records singer, was born in Bastrop.

- Sam Little, member of Louisiana House of Representatives from Bastrop from 2008 to 2012

- Bob Love, NBA Basketball Player

- Jim Looney, NFL player

- Charles McDonald, member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1991 to 2008

- Calvin Natt, National Basketball Association player who was born in Monroe, but attended Bastrop High School, later NLU and was an NBA All-Star with the Denver Nuggets.

- Kenny Natt, National Basketball Association younger brother of Kenny Natt, Drafted by Indiana Pacers in 1980

- Hugh G. Parker, Jr., American architect; designed many public and private buildings in North Louisiana

- Willie Parker, NFL and WFL player

- Rueben Randle, LSU Tigers football, Wide Receiver, and led Bastrop High School to a State Championship, was drafted by the New York Giants in the 2012 draft

- Shane Reynolds, Major League Baseball player[31]

- John Wesley Ryles, Country singer was born in Bastrop in 1950.

- Talance Sawyer, was also born in Bastrop and later played for the Minnesota Vikings.

- Dylan Scott, country music singer-songwriter

- Dorothy Garrett Smith, first woman president of the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, 1989 to her death in 1990[32]

- Pat Williams, NFL player who was born in Bastrop and played for the Minnesota Vikings.

References

- ↑ "2016 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 2, 2017.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "Bastrop (city), Louisiana". quickfacts.census.gov. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ↑ John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, pp. 413–414

- 1 2 http://www.preserveamerica.gov/PAcommunity-bastropLA.html

- ↑ "Ann Barham obituary". The Monroe News-Star. December 11, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ↑ Greg Hilburn, "Jindal visits region" Archived August 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., The Monroe News-Star, December 13, 2008

- ↑ Greg Hilburn, "Bastrop mill closes; 550 lose jobs" Archived August 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., Monroe News Star, November 22, 2008, p. 1

- ↑ Greg Hilburn, "Jindal: Bastrop is a top priority: State will do all it can to prop up community" Archived August 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine., Monroe News Star, November 25, 2008

- 1 2 3 "Greg Hilburn and Robbie Evans, "Pilgrim's Pride decision a bombshell: Sites closing in Arcadia, Athens, Choudrant, Farmerville". Shreveport Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2009.

- ↑ "BRAC in the News: Blanco argues against use of megafund". Brac.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 19, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-28.

- ↑ http://www.thepineywoods.com/PelletsJan13.html/%5B%5D

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ 2010 census report for Bastrop, Louisiana

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Matthew Hamilton, "Alford-Olive unseats Hawkins in Bastrop upset", Monroe News-Star, April 5, 2009

- ↑ "Cole Avery, "New Bastrop mayor sets goals for first term"". Monroe News-Star, July 3, 2013. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ http://www.ulm.edu/upa/

- 1 2 3 http://www.city-data.com/city/Bastrop-Louisiana.html

- ↑ http://www.latech.edu/ir/assets/fact-book-2007-2011.pdf

- 1 2 3 Southwell, Zack (May 21, 2011). "Prayer sparks controversy in Bastrop". The Star. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ↑ Lebo, Lauri. "Student Says He’s Ostracized for Objecting to Graduation Prayer". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- ↑ "LaBreeska Hemphill". The Monroe News-Star. December 13, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Henderson, William Kennon". Louisiana Historical Association, A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (lahistory.org). Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Shane Reynolds Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved February 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Heart Attack Claims Dorothy Smith", Minden Press-Herald, August 9, 1990, p. 1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bastrop, Louisiana. |

- City of Bastrop

- Bastrop Progress Community Progress Site for Bastrop, LA

- Bastrop Daily Enterprise

- (http://www.mpsb.us)