Prague

| Prague Praha | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital city | |||

| Hlavní město Praha | |||

|

Montage of Prague, clockwise from top: Old Town Hall, Charles Bridge, Old Town Square, the Malá Strana, the Dancing House, St. Vitus Cathedral | |||

| |||

|

Motto: "Praga Caput Rei publicae" (Latin)[1] | |||

| |||

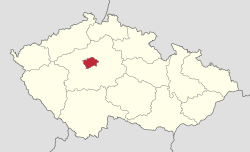

| Coordinates: 50°05′N 14°25′E / 50.083°N 14.417°ECoordinates: 50°05′N 14°25′E / 50.083°N 14.417°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Founded | 6th century | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Adriana Krnáčová (ANO) | ||

| Area[3] | |||

| • Urban | 496 km2 (192 sq mi) | ||

| Highest elevation | 399 m (1,309 ft) | ||

| Lowest elevation | 177 m (581 ft) | ||

| Population (2017)[4] | |||

| • Capital city | 1,282,496 | ||

| • Metro | 2,156,097 [5] | ||

| Demonym(s) | Praguer | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 100 00 – 199 00 | ||

| Vehicle registration | A | ||

| NUTS code | 2012 | ||

| – Total | €40 billion | ||

| – Per capita | €32,000() | ||

| Website | praha.eu | ||

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |||

| Official name | Historic Centre of Prague | ||

| Criteria |

Cultural: (ii), (iv), (vi) | ||

| Reference | 616 | ||

| Inscription | 1992 (16th Session) | ||

| Extensions | 2012 | ||

| Endangered | – | ||

Prague (/ˈprɑːɡ/; Czech: Praha, [ˈpraɦa], German: Prag) is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. It is the 14th largest city in the European Union.[6] It is also the historical capital of Bohemia. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.4 million people, while its larger urban zone is estimated to have a population of 2.2 million.[7] The city has a temperate climate, with warm summers and chilly winters.

Prague has been a political, cultural, and economic centre of central Europe with waxing and waning fortunes during its history. Founded during the Romanesque and flourishing by the Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque eras, Prague was the capital of the kingdom of Bohemia and the main residence of several Holy Roman Emperors, most notably of Charles IV (r. 1346–1378).[8] It was an important city to the Habsburg Monarchy and its Austro-Hungarian Empire. The city played major roles in the Bohemian and Protestant Reformation, the Thirty Years' War, and in 20th-century history as the capital of Czechoslovakia, during both World Wars and the post-war Communist era.[9]

Prague is home to a number of famous cultural attractions, many of which survived the violence and destruction of 20th-century Europe. Main attractions include the Prague Castle, the Charles Bridge, Old Town Square with the Prague astronomical clock, the Jewish Quarter, Petřín hill and Vyšehrad. Since 1992, the extensive historic centre of Prague has been included in the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

The city has more than ten major museums, along with numerous theatres, galleries, cinemas, and other historical exhibits. An extensive modern public transportation system connects the city. Also, it is home to a wide range of public and private schools, including Charles University in Prague, the oldest university in Central Europe.[10]

Prague is classified as a "Alpha-" global city according to GaWC studies.[11] Prague ranked sixth in the Tripadvisor world list of best destinations in 2016.[12] Its rich history makes it a popular tourist destination, and the city receives more than 6.4 million international visitors annually, as of 2014. Prague is the fifth most visited European city after London, Paris, Istanbul and Rome.[13]

History

During the thousand years of its existence, the city grew from a settlement stretching from Prague Castle in the north to the fort of Vyšehrad in the south, becoming the capital of a modern European country, the Czech Republic, a member state of the European Union.

Early history

The region was settled as early as the Paleolithic age.[14] Around the fifth and fourth century BC, the Celts appeared in the area, later establishing settlements including an oppidum in Závist, a present-day suburb of Prague, and giving name to the region of Bohemia, "home of the Boii".[14][15] In the last century BC, the Celts were slowly driven away by Germanic tribes (Marcomanni, Quadi, Lombards and possibly the Suebi), leading some to place the seat of the Marcomanni king Maroboduus on the southern Prague's site Závist.[16][17] Around the area where present-day Prague stands, the 2nd century map of Ptolemaios mentioned a Germanic city called Casurgis.[18]

In the late 5th century AD, during the great Migration Period following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, the Germanic tribes living in Bohemia moved westwards and, in the 6th century, the Slavic tribes settled Central Europe and the area of present-day Prague. In the following century, the Czech tribes built several fortified settlements in the area, most notably in Levý Hradec, Butovice and in the Šárka valley.[14]

The construction of what came to be known as the Prague Castle began near the end of the 9th century, with a fortified settlement already existing on the site in the year 800.[19] The first masonry under Prague Castle dates from the year 885 at the latest.[20] The other prominent Prague fort, the Přemyslid fort Vyšehrad, was founded in the 10th century, some 70 years later than Prague Castle.[21] Prague Castle is dominated by the cathedral, which was founded in 1344, but completed in the 20th century.

The legendary origins of Prague attribute its foundation to the 8th century Czech duchess and prophetess Libuše and her husband, Přemysl, founder of the Přemyslid dynasty. Legend says that Libuše came out on a rocky cliff high above the Vltava and prophesied: "I see a great city whose glory will touch the stars." She ordered a castle and a town called Praha to be built on the site.[14]

A 17th century Jewish chronicler David Solomon Ganz, citing Cyriacus Spangenberg, claimed that the city was founded as Boihaem in c. 1306 BC by an ancient king, Boyya.[17]

The region became the seat of the dukes, and later kings of Bohemia. Under Roman Emperor Otto II the area became a bishopric in 973. Until Prague was elevated to archbishopric in 1344, it was under the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Mainz.

Prague was an important seat for trading where merchants from all of Europe settled, including many Jews, as recalled in 965 by the Hispano-Jewish merchant and traveller Ibrahim ibn Ya'qub. The Old New Synagogue of 1270 still stands. Prague contained an important slave market.[22]

At the site of the ford in the Vltava river, King Vladislaus I had the first bridge built in 1170, the Judith Bridge (Juditin most), named in honour of his wife Judith of Thuringia. This bridge was destroyed by a flood in 1342. Some of the original foundation stones of that bridge remain.

In 1257, under King Ottokar II, Malá Strana ("Lesser Quarter") was founded in Prague on the site of an older village in what would become the Hradčany (Prague Castle) area. This was the district of the German people, who had the right to administer the law autonomously, pursuant to Magdeburg rights. The new district was on the bank opposite of the Staré Město ("Old Town"), which had borough status and was bordered by a line of walls and fortifications.

The era of Charles IV

Prague flourished during the 14th-century reign (1346–1378) of Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and the king of Bohemia of the new Luxembourg dynasty. As King of Bohemia and Holy Roman Emperor, he transformed Prague into an imperial capital and it was at that time the third-largest city in Europe (after Rome and Constantinople).

He ordered the building of the New Town (Nové Město) adjacent to the Old Town and laid out the design himself. The Charles Bridge, replacing the Judith Bridge destroyed in the flood just prior to his reign, was erected to connect the east bank districts to the Malá Strana and castle area. On 9 July 1357 at 5:31 am, Charles IV personally laid the first foundation stone for the Charles Bridge. The exact time of laying the first foundation stone is known because the palindromic number 135797531 was carved into the Old Town bridge tower having been chosen by the royal astrologists and numerologists as the best time for starting the bridge construction.[23] In 1347, he founded Charles University, which remains the oldest university in Central Europe.

He began construction of the Gothic Saint Vitus Cathedral, within the largest of the Prague Castle courtyards, on the site of the Romanesque rotunda there. Prague was elevated to an archbishopric in 1344, the year the cathedral was begun.

The city had a mint and was a centre of trade for German and Italian bankers and merchants. The social order, however, became more turbulent due to the rising power of the craftsmen's guilds (themselves often torn by internal fights), and the increasing number of poor people.

The Hunger Wall, a substantial fortification wall south of Malá Strana and the Castle area, was built during a famine in the 1360s. The work is reputed to have been ordered by Charles IV as a means of providing employment and food to the workers and their families.

Charles IV died in 1378. During the reign of his son, King Wenceslaus IV (1378–1419), a period of intense turmoil ensued. During Easter 1389, members of the Prague clergy announced that Jews had desecrated the host (Eucharistic wafer) and the clergy encouraged mobs to pillage, ransack and burn the Jewish quarter. Nearly the entire Jewish population of Prague (3,000 people) perished.[24][25]

.jpg)

Jan Hus, a theologian and rector at the Charles University, preached in Prague. In 1402, he began giving sermons in the Bethlehem Chapel. Inspired by John Wycliffe, these sermons focused on what were seen as radical reforms of a corrupt Church. Having become too dangerous for the political and religious establishment, Hus was summoned to the Council of Constance, put on trial for heresy, and burned at the stake in Constanz in 1415.

Four years later Prague experienced its first defenestration, when the people rebelled under the command of the Prague priest Jan Želivský. Hus' death, coupled with Czech proto-nationalism and proto-Protestantism, had spurred the Hussite Wars. Peasant rebels, led by the general Jan Žižka, along with Hussite troops from Prague, defeated Emperor Sigismund, in the Battle of Vítkov Hill in 1420.

During the Hussite Wars when the City of Prague was attacked by "Crusader" and mercenary forces, the city militia fought bravely under the Prague Banner. This swallow-tailed banner is approximately 4 by 6 feet (1.2 by 1.8 metres), with a red field sprinkled with small white fleurs-de-lis, and a silver old Town Coat-of-Arms in the centre. The words "PÁN BŮH POMOC NAŠE" (The Lord is our Relief) appeared above the coat-of-arms, with a Hussite chalice centred on the top. Near the swallow-tails is a crescent shaped golden sun with rays protruding.

One of these banners was captured by Swedish troops in Battle of Prague (1648), when they captured the western bank of the Vltava river and were repulsed from the eastern bank, they placed it in the Royal Military Museum in Stockholm; although this flag still exists, it is in very poor condition. They also took the Codex Gigas and the Codex Argenteus. The earliest evidence indicates that a gonfalon with a municipal charge painted on it was used for Old Town as early as 1419. Since this city militia flag was in use before 1477 and during the Hussite Wars, it is the oldest still preserved municipal flag of Bohemia.

In the following two centuries, Prague strengthened its role as a merchant city. Many noteworthy Gothic buildings[27][28] were erected and Vladislav Hall of the Prague Castle was added.

Habsburg era

_102.jpg)

In 1526, the Bohemian estates elected Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg. The fervent Catholicism of its members was to bring them into conflict in Bohemia, and then in Prague, where Protestant ideas were gaining popularity.[29] These problems were not pre-eminent under Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, elected King of Bohemia in 1576, who chose Prague as his home. He lived in the Prague Castle, where his court welcomed not only astrologers and magicians but also scientists, musicians, and artists. Rudolf was an art lover too, and Prague became the capital of European culture. This was a prosperous period for the city: famous people living there in that age include the astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, the painter Arcimboldo, the alchemists Edward Kelley and John Dee, the poet Elizabeth Jane Weston, and others.

In 1618, the famous second defenestration of Prague provoked the Thirty Years' War, a particularly harsh period for Prague and Bohemia. Ferdinand II of Habsburg was deposed, and his place as King of Bohemia taken by Frederick V, Elector Palatine; however his army was crushed in the Battle of White Mountain (1620) not far from the city. Following this in 1621 was an execution of 27 Czech leaders (involved in the uprising) in Old Town Square and the exiling of many others. The city suffered subsequently during the war under Saxon (1631) and Battle of Prague (1648).[30] Prague began a steady decline which reduced the population from the 60,000 it had had in the years before the war to 20,000. In the second half of the 17th century Prague's population began to grow again. Jews have been in Prague since the end of the 10th century and, by 1708, they accounted for about a quarter of Prague's population.[31]

In 1689, a great fire devastated Prague, but this spurred a renovation and a rebuilding of the city. In 1713–14, a major outbreak of plague hit Prague one last time, killing 12,000 to 13,000 people.[32]

In 1744 Frederick the Great of Prussia invaded Bohemia and obtained possession of Prague after a severe and prolonged bombardment, in the course of which a large part of the town was destroyed.[33] In the Battle of Prague in 1757 Prussian bombardment[33] destroyed more than one quarter of the city and heavily damaged St. Vitus Cathedral. However next month after the Battle of Kolín, Frederick the Great lost and had to retreat from Bohemia.

The economic rise continued through the 18th century, and the city in 1771 had 80,000 inhabitants. Many of these were rich merchants and nobles who enriched the city with a host of palaces, churches and gardens full of art and music, creating a Baroque style renowned throughout the world.

In 1784, under Joseph II, the four municipalities of Malá Strana, Nové Město, Staré Město, and Hradčany were merged into a single entity. The Jewish district, called Josefov, was included only in 1850. The Industrial Revolution had a strong effect in Prague, as factories could take advantage of the coal mines and ironworks of the nearby region. A first suburb, Karlín, was created in 1817, and twenty years later the population exceeded 100,000.

The revolutions in Europe in 1848 also touched Prague, but they were fiercely suppressed. In the following years the Czech National Revival began its rise, until it gained the majority in the town council in 1861. Prague had a German-speaking majority in 1848, but by 1880 the number of German speakers had decreased to 14% (42,000), and by 1910 to 6.7% (37,000), due to a massive increase of the city's overall population caused by the influx of Czechs from the rest of Bohemia and Moravia and also due to return of social status importance of the Czech language.

20th century

First Czechoslovak Republic

World War I ended with the defeat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the creation of Czechoslovakia. Prague was chosen as its capital and Prague Castle as the seat of president Tomáš Masaryk. At this time Prague was a true European capital with highly developed industry. By 1930, the population had risen to 850,000.

Second World War

Hitler ordered the German Army to enter Prague on 15 March 1939, and from Prague Castle proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate. For most of its history, Prague had been a multi-ethnic city with important Czech, German and (mostly native German-speaking) Jewish populations. From 1939, when the country was occupied by Nazi Germany, and during the Second World War, most Jews were deported and killed by the Germans. In 1942, Prague was witness to the assassination of one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany – Reinhard Heydrich – during Operation Anthropoid, accomplished by Czechoslovak national heroes Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš. Hitler ordered bloody reprisals.

At the end of the war, Prague suffered several bombing raids by the US Army Air Forces. 701 people were killed, more than 1,000 people were injured and some of buildings, factories and historical landmarks (Emmaus Monastery, Faust House, Vinohrady Synagogue) were destroyed.[34] Many historic structures in Prague, however, escaped the destruction of the war and the damage was small compared to the total destruction of many other cities in that time. According to American pilots, it was the result of a navigational mistake.

On 5 May 1945, two days before Germany capitulated, an uprising against Germany occurred. Four days later, the 3rd Shock Army of the Red Army liberated the city. The majority (about 50,000 people) of the German population of Prague either fled or were expelled by the Beneš decrees in the aftermath of the war.

Cold War

Prague was a city in the territory of military and political control of the Soviet Union (see Iron Curtain). The biggest Stalin Monument was unveiled on Letná hill in 1955 and destroyed in 1962. The 4th Czechoslovakian Writers' Congress held in the city in June 1967 took a strong position against the regime. On 31 October 1967 students demonstrated at Strahov. This spurred the new secretary of the Communist Party, Alexander Dubček, to proclaim a new deal in his city's and country's life, starting the short-lived season of the "socialism with a human face". It was the "Prague Spring", which aimed at the renovation of institutions in a democratic way. The other Warsaw Pact member countries, except Romania and Albania, reacted with the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the capital on 21 August 1968 by tanks, suppressing any attempt at reform. Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc committed suicide by self-immolation in January and February 1969 to protest against the "normalization" of the country.

After Velvet Revolution

In 1989, after the riot police beat back a peaceful student demonstration, the Velvet Revolution crowded the streets of Prague, and the Czechoslovak capital benefited greatly from the new mood. In 1993, after the split of Czechoslovakia, Prague became the capital city of the new Czech Republic. From 1995 high-rise buildings began to be built in Prague in large quantities. In the late 1990s, Prague again became an important cultural centre of Europe and was notably influenced by globalisation. In 2000, IMF and World Bank summits took place in Prague. In 2002, Prague suffered from widespread floods that damaged buildings and its underground transport system.

Prague launched a bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics,[35] but failed to make the candidate city shortlist. In June 2009, as the result of financial pressures from the global recession, Prague's officials also chose to cancel the city's planned bid for the 2020 Summer Olympics.[36]

Name

The Czech name Praha is derived from an old Slavic word, práh, which means "ford" or "rapid", referring to the city's origin at a crossing point of the Vltava river.[37] The same etymology is associated with the Praga district of Warsaw.[38]

Another view to the origin of name is also related to the Czech word práh (in the mean of a threshold) and a legendary etymology connects the name of the city with princess Libuše, prophetess and a wife of mythical founder of the Přemyslid dynasty. She is said to have ordered the city "to be built where a man hews a threshold of his house". The Czech práh might thus be understood to refer to rapids or fords in the river, the edge of which could have acted as a means of fording the river – thus providing a "threshold" to the castle.

Another derivation of the name Praha is suggested from na prazě, the original term for the shale hillside rock upon which the original castle was built. At that time, the castle was surrounded by forests, covering the nine hills of the future city – the Old Town on the opposite side of the river, as well as the Lesser Town beneath the existing castle, appeared only later.[39]

The English spelling of the city's name is borrowed from French. Prague is also called the "City of a Hundred Spires", based on a count by 19th century mathematician Bernard Bolzano, today's count is estimated by Prague Information Service at 500.[40] Nicknames for Prague have also included: the Golden City, the Mother of Cities and the Heart of Europe.[41]

Geography

Prague is situated on the Vltava river, at 50°05"N and 14°27"E.[42] in the centre of the Bohemian Basin. Prague is approximately at the same latitude as Frankfurt, Germany;[43] Paris, France;[44] and Vancouver, Canada.[45]

Population

According to the 2011 census, about 14% of the city inhabitants were foreigners, the highest proportion in the country.[46]

Development of the Prague population since 1378:[47][48][49]

| Year | 1378 | 1500 | 1610 | 1798 | 1880 | 1930 | 1961 | 1980 | 1995 | 2005 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 40,000 | 30,000 | 60,000 | 79,000 | 350,000 | 950,000 | 1,130,000 | 1,190,000 | 1,210,000 | 1,180,000 | 1,267,449 |

| Foreign residents in the city (2016)[50] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Population | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47,332 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28,973 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22,156 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12,179 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,517 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Climate

The city of Prague lies between oceanic climate and humid continental climate (Köppen Cfb/Dfb). The winters are relatively cold with average temperatures at about freezing point, and with very little sunshine. Snow cover can be common between mid-November and late March although snow accumulations of more than 20 cm (8 in) are infrequent. There are also a few periods of mild temperatures in winter. Summers usually bring plenty of sunshine and the average high temperature of 24 °C (75 °F). Nights can be quite cool even in summer, though. Precipitation in Prague (and most of the Bohemian lowland) is rather low (just over 500 mm [20 in] per year) since it is located in the rain shadow of the Sudetes and other mountain ranges. The driest season is usually winter while late spring and summer can bring quite heavy rain, especially in form of thundershowers. Temperature inversions are relatively common between mid-October and mid-March bringing foggy, cold days and sometimes moderate air pollution. Prague is also a windy city with common sustained western winds and an average wind speed of 16 km/h (9.9 mph) that often help break temperature inversions and clear the air in cold months.

| Climate data for Prague (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.5 (90.5) |

37.2 (99) |

37.8 (100) |

37.4 (99.3) |

33.1 (91.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

37.8 (100) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

18.9 (66) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.1 (61) |

18.2 (64.8) |

17.8 (64) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

0.0 (32) |

2.9 (37.2) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.5 (−17.5) |

−27.1 (−16.8) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

−8 (18) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.9 (35.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

6.4 (43.5) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−24.8 (−12.6) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 23.5 (0.925) |

22.6 (0.89) |

28.1 (1.106) |

38.2 (1.504) |

77.2 (3.039) |

72.7 (2.862) |

66.2 (2.606) |

69.6 (2.74) |

40.0 (1.575) |

30.5 (1.201) |

31.9 (1.256) |

25.3 (0.996) |

525.8 (20.701) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 17.9 (7.05) |

15.9 (6.26) |

10.3 (4.06) |

2.9 (1.14) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0 (0) |

0.1 (0.04) |

8.4 (3.31) |

15.9 (6.26) |

71.4 (28.11) |

| Average precipitation days | 6.8 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 7.3 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 90.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 83 | 77 | 69 | 70 | 71 | 70 | 71 | 76 | 81 | 87 | 88 | 77 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 50.0 | 72.4 | 124.7 | 167.6 | 214.0 | 218.3 | 226.2 | 212.3 | 161.0 | 120.8 | 53.9 | 46.7 | 1,667.9 |

| Source #1: Pogoda.ru.net[51] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: NOAA[52] | |||||||||||||

Culture

The city is traditionally one of the cultural centres of Europe, hosting many cultural events. Some of the significant cultural institutions include the National Theatre (Národní Divadlo) and the Estates Theatre (Stavovské or Tylovo or Nosticovo divadlo), where the premières of Mozart's Don Giovanni and La clemenza di Tito were held. Other major cultural institutions are the Rudolfinum which is home to the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and the Municipal House which is home to the Prague Symphony Orchestra. The Prague State Opera (Státní opera) performs at the Smetana Theatre.

The city has many world-class museums, including the National Museum (Národní muzeum), the Museum of the Capital City of Prague, the Jewish Museum in Prague, the Alfons Mucha Museum, the African-Prague Museum, the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, the Náprstek Museum (Náprstkovo Muzeum), the Josef Sudek Gallery and The Josef Sudek Studio, the National Library and the National Gallery, which manages the largest collection of art in the Czech Republic.

There are hundreds of concert halls, galleries, cinemas and music clubs in the city. It hosts music festivals including the Prague Spring International Music Festival, the Prague Autumn International Music Festival, the Prague International Organ Festival and the Prague International Jazz Festival. Film festivals include the Febiofest, the One World Film Festival and Echoes of the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. The city also hosts the Prague Writers' Festival, the Prague Folklore Days, Prague Advent Choral Meeting the Summer Shakespeare Festival,[53] the Prague Fringe Festival, the World Roma Festival, as well as the hundreds of Vernissages and fashion shows.

Many films have been made at Barrandov Studios and at Prague Studios. Hollywood films set in Prague include Mission Impossible, xXx, Blade II, Alien vs. Predator, Doom, Chronicles of Narnia, Hellboy, Red Tails, Children of Dune and Van Helsing.[54] Other Czech films shot in Prague include Empties, EuroTrip, Amadeus and The Fifth Horseman is Fear. Also, the romantic music video "Never Tear Us Apart" by INXS, "Diamonds from Sierra Leone" by Kanye West was shot in the city, and features shots of the Charles Bridge and the Astronomical Clock, among other famous landmarks. Rihanna's "Don't Stop the Music" video was filmed at Prague's Radost FX Club. The city was also the setting for the film Dungeons and Dragons in 2000. The music video "Silver and Cold" by AFI, an American rock band, was also filmed in Prague. Many Indian films have also been filmed in the city including Yuvraaj, Drona and Rockstar.

Forbes Traveler magazine and TripAdvisor listed Prague Zoo among the world's best zoos.[55]

With the growth of low-cost airlines in Europe, Prague has become a popular weekend city destination allowing tourists to visit its many museums and cultural sites as well as try its famous Czech beers and hearty cuisine.

The city has many buildings by renowned architects, including Adolf Loos (Villa Müller), Frank O. Gehry (Dancing House) and Jean Nouvel (Golden Angel).

Recent major events held in Prague:

- International Monetary Fund and World Bank Summit 2000

- NATO Summit 2002

- International Olympic Committee Session 2004

- IAU General Assembly 2006 (Definition of planet)

- EU & USA Summit 2009

- Czech Presidency of the Council of the European Union 2009

- USA & Russia Summit 2010 (signing of the New START treaty)

Cuisine

In 2008 the Allegro restaurant received the first Michelin star in the whole of the post-Communist part of Central Europe. It retained its star until 2011. As of 2016 there are three Michelin-starred restaurants in Prague: Alcron, La Degustation Bohême Bourgeoise and Field.

In Malá Strana, Staré Město, Žižkov and Nusle there are hundreds of restaurants, bars and pubs, especially with Czech beer. Prague also hosts the Czech Beer Festival (Český pivní festival), which is the largest beer festival in the Czech Republic, held for 17 days every year in May. At the festival, more than 70 brands of Czech beer can be tasted.

Prague is home to many breweries including:

- Pivovary Staropramen (Praha 5)

- První novoměstský restaurační pivovar (Praha 1)

- Pivovar U Fleků (Praha 1)

- Klášterní pivovar Strahov (Praha 1)

- Pivovar Pražský most u Valšů (Praha 1)

- Pivovarský Hotel U Medvídků (Praha 1)

- Pivovarský dům (Praha 2)

- Jihoměstský pivovar (Praha 4)

- Sousedský pivovar U Bansethů (Praha 4)

- Vyukový a výzkumný pivovar – Suchdolský Jeník (Praha 6)

- Pivovar U Bulovky (Praha 8)

Economy

Prague's economy accounts for 25% of the Czech GDP[56] making it the highest performing regional economy of the country. According to the Eurostat, as of 2007, its GDP per capita in purchasing power standard is €42,800. Prague ranked the 5th best-performing European NUTS two-level region at 172 percent of the EU-27 average.[57]

The city is the site of the European headquarters of many international companies.

Prague employs almost a fifth of the entire Czech workforce, and its wages are significantly above average (~+25%). In December 2015, average salaries available in Prague reached 35,853 CZK, an annual increase of 3.4%, which was nevertheless lower than national increase of 3.9% both in nominal and real terms. (Inflation in Prague was 0.5% in December, compared with 0.1% nationally.)[57][58] Since 1990, the city's economic structure has shifted from industrial to service-oriented. Industry is present in sectors such as pharmaceuticals, printing, food processing, manufacture of transport equipment, computer technology and electrical engineering. In the service sector, financial and commercial services, trade, restaurants, hospitality and public administration are the most significant. Services account for around 80 percent of employment. There are 800,000 employees in Prague, including 120,000 commuters.[56] The number of (legally registered) foreign residents in Prague has been increasing in spite of the country's economic downturn. As of March 2010, 148,035 foreign workers were reported to be living in the city making up about 18 percent of the workforce, up from 131,132 in 2008.[59] Approximately one-fifth of all investment in the Czech Republic takes place in the city.

Almost one-half of the national income from tourism is spent in Prague. The city offers approximately 73,000 beds in accommodation facilities, most of which were built after 1990, including almost 51,000 beds in hotels and boarding houses.

%2C_Vltava_River%2C_Prague%2C_2015.jpg)

From the late 1990s to late 2000s, the city was a popular filming location for international productions such as Hollywood and Bollywood motion pictures. A combination of architecture, low costs and the existing motion picture infrastructure have proven attractive to international film production companies.

The modern economy of Prague is largely service and export-based and, in a 2010 survey, the city was named the best city in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) for business.[60]

In 2005, Prague was deemed among the three best cities in Central and Eastern Europe according to The Economist's livability rankings.[61] The city was named as a top-tier nexus city for innovation across multiple sectors of the global innovation economy, placing 29th globally out of 289 cities, ahead of Brussels and Helsinki for innovation in 2010 in 2thinknow annual analysts Innovation Cities Index.[62] Na příkopě in New Town is the most expensive street in the whole of Central Europe.[63]

In the Eurostat research, Prague ranked fifth among Europe's 271 regions in terms of gross domestic product per inhabitant, achieving 172 percent of the EU average. It ranked just above Paris and well above the country as a whole, which achieved 80 percent of the EU average.[64][65]

Companies with highest turnover in the region in 2014:[66]

| Name | Turnover, mld. Kč |

|---|---|

| ČEZ | 200.8 |

| Agrofert | 166.8 |

| RWE Supply & Trading CZ | 146.1 |

Prague is also the site of some of the most important offices and institutions of the Czech Republic.

- President of the Czech Republic

- The Government and both houses of Parliament

- Ministries and other national offices (Industrial Property Office, Czech Statistical Office, National Security Authority etc.)

- Czech National Bank

- Czech Television and other major broadcasters

- Radio Free Europe – Radio Liberty

- Galileo global navigation project

- Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic

Tourism

| Country | Number |

|---|---|

| | 877,352 |

| | 453,105 |

| | 410,527 |

| | 302,278 |

| | 280,641 |

| | 280,479 |

| | 236,449 |

| | 228,833 |

| | 226,105 |

| | 225,890 |

Since the fall of the Iron Curtain, Prague has become one of the world's most popular tourist destinations. Prague suffered considerably less damage during World War II than some other major cities in the region, allowing most of its historic architecture to stay true to form. It contains one of the world's most pristine and varied collections of architecture, from Romanesque, to Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Gothic, Art Nouveau, Cubist, Neo-Classical and ultra-modern.

Prague is classified as an "Alpha-" global city according to GaWC studies, comparable to Vienna, Seoul and Washington, D.C. Prague ranked sixth in the Tripadvisor world list of best destinations in 2016.[12] Its rich history makes it a popular tourist destination, and the city receives more than 6.4 million international visitors annually, as of 2014. Prague is the fifth most visited European city after London, Paris, Istanbul and Rome.[13] Prague's low cost of living makes it a popular destination for expats relocating to Europe.[68]

Hradčany and Lesser Town (Malá Strana)

- Prague Castle with the St. Vitus Cathedral which stores the Czech Crown Jewels

- The picturesque Charles Bridge (Karlův most)

- The Baroque Saint Nicholas Church

- Church of Our Lady Victorious and Infant Jesus of Prague

- Písek Gate, one of the last preserved city gate of Baroque fortification

- Petřín Hill with Petřín Lookout Tower, Mirror Maze and Petřín funicular

- Lennon Wall

- The Franz Kafka Museum

- Kampa Island, an island with a view of the Charles Bridge[69]

Old Town (Staré Město) and Josefov

- The Astronomical Clock (Orloj) on Old Town City Hall

- The Gothic Church of Our Lady before Týn (Kostel Matky Boží před Týnem) from the 14th century with 80 m high towers

- The vaulted Gothic Old New Synagogue (Staronová Synagoga) of 1270

- Old Jewish Cemetery

- Powder Tower (Prašná brána), a Gothic tower of the old city gates

- Spanish Synagogue with its beautiful interior

- Old Town Square (Staroměstské náměstí) with gothic and baroque architectural styles

- The art nouveau Municipal House, a major civic landmark and concert hall known for its Art Nouveau architectural style and political history in the Czech Republic.

- Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague, with an extensive collections including glass, furniture, textile, toys, Art Nouveau, Cubism and Art Deco

- Clam-Gallas Palace, a baroque palace from 1713

New Town (Nové Město)

- Busy and historic Wenceslas Square

- The neo-renaissance National Museum with large scientific and historical collections

- The National Theatre, a neo-Renaissance building with golden roof, alongside the banks of the Vltava river

- The deconstructivist Dancing House (Fred and Ginger Building)

- Charles Square, the largest medieval square in Europe (now turned into a park)

- The Emmaus monastery and WW Memorial "Prague to Its Victorious Sons" at Palacky Square (Palackého náměstí)

- The museum of the Heydrich assassination in the crypt of the Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius

- Stiassny's Jubilee Synagogue is the largest in Prague

- The Mucha Museum, showcasing the Art Nouveau works of Alphonse Mucha

Vinohrady and Žižkov

- National Monument in Vitkov with a large bronze equestrian statue of Jan Žižka in Vítkov Park, Žižkov – Prague 3

- The neo-Gothic Church of St. Ludmila at Náměstí Míru (Peace Square) in Vinohrady

- Žižkov Television Tower with sculptures of crawling babies

- New Jewish Cemetery in Olšany, location of Franz Kafka's grave – Prague 3

- The Roman Catholic Sacred Heart Church at George of Poděbrady Square (Jiřího z Poděbrad)

- The Vinohrady grand Neo-Renaissance, Art Nouveau, Pseudo Baroque, and Neo-Gothic buildings in the area between Náměstí Míru (Peace Square), Jiřího z Poděbrad square and Havlíčkovy sady park[70]

Other places

- Vyšehrad Castle with Basilica of St Peter and St Paul, Vyšehrad cemetery and Prague oldest Rotunda of St. Martin

- The Prague Metronome at Letná Park, a giant, functional metronome that looms over the city

- Prague Zoo in Troja, selected as one of the world's best zoos by Forbes magazine[55]

- Industrial Palace (Průmyslový palác), Křižík's Light fountain, funfair Lunapark and Sea World Aquarium in Výstaviště compound in Holešovice

- Letohrádek Hvězda (Star Villa) in Liboc, a renaissance villa in the shape of a six-pointed star surrounded by a game reserve

- National Gallery in Prague with large collection of Czech and international paintings and sculptures by artists such as Mucha, Kupka, Picasso, Monet or Van Gogh

- Anděl, a busy part of the city with modern architecture and a shopping mall

- The large Nusle Bridge, spans the Nusle Valley, linking New Town to Pankrác, with the Metro running underneath the road

- Strahov Monastery, an old Czech premonstratensian abbey founded in 1149 and monastic library

The Charles Bridge is a historic bridge from the 14th century

The Charles Bridge is a historic bridge from the 14th century Prague Castle is the biggest ancient castle in the world

Prague Castle is the biggest ancient castle in the world

- St. Nicholas Church in Malá Strana is the best example of the Baroque style in Prague

Vyšehrad fortress contains Basilica of St Peter and St Paul, the Vyšehrad Cemetery and the oldest Rotunda of St. Martin

Vyšehrad fortress contains Basilica of St Peter and St Paul, the Vyšehrad Cemetery and the oldest Rotunda of St. Martin- View of Pařížská st. from Letná Park

National Theatre offers opera, drama, ballet and other performances

National Theatre offers opera, drama, ballet and other performances

Old New Synagogue is Europe's oldest active synagogue. Legend has Golem lying in the loft

Old New Synagogue is Europe's oldest active synagogue. Legend has Golem lying in the loft- National Monument on Vítkov Hill, the statue of Jan Žižka is the third largest bronze equestrian statue in the world

- Prague Zoo, selected as the fourth best zoo in the world by TripAdvisor

Historic Centre of Prague was declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1992.

Historic Centre of Prague was declared World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1992.

Education

Twelve universities, and a number of colleges and schools are located in the city, including:

Public universities

- Charles University founded in 1348, the oldest university in Central Europe

- Czech Technical University (ČVUT) founded in 1707

- Institute of Chemical Technology (VŠCHT) founded in 1920

- University of Economics (VŠE) founded in 1953

- Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (ČZU) founded in 1906/1952

Public arts academies

- Academy of Fine Arts (AVU) founded in 1800

- Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design (VŠUP) founded in 1885

- Academy of Performing Arts (AMU) founded in 1945

Private schools

- University of New York in Prague (UNYP) founded in 1998

- International School of Prague (ISP) founded in 1948

- Anglo-American University (AAU) founded in 1990

- University of Northern Virginia in Prague (UNVA) founded in 1998

- Architectural Institute in Prague (ARCHIP) founded in 2010

- The University of Finance and Administration (VSFS) founded in 1999

- Metropolitan University Prague (MUP) founded in 2001

- Prague College founded in 2004

International institutions

Science, research and hi-tech centres

The region city of Prague is an important centre of research. It is the seat of 39 out of 54 institutes of the Czech Academy of Sciences, including the largest ones, the Institute of Physics, the Institute of Microbiology and the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry. It is also a seat of 10 public research institutes, four business incubators and large hospitals performing research and development activities such as the Institute for Clinical and Experimental Medicine in Prague or the Motol University Hospital. Universities seated in Prague (see section Colleges and Universities) also represent important centres of science and research activities.

As of 2008, there were 13,000 researchers (out of 30,000 in the Czech Republic, counted in full-time equivalent), representing 3% share of Prague's economically active population. Gross expenditure on research and development accounted for €901.3 million (41.5% of country's total).[71]

Some well-known multinational companies have established research and development facilities in Prague, among them Siemens, Honeywell and Sun Microsystems.

Prague was selected to host administration of the EU satellite navigation system Galileo. It started to provide its first services in December 2016 and full completion is expected by 2020.

Transport

Public transportation

The public transport infrastructure (PID, Pražská integrovaná doprava) consists of a heavily used integrated transport system of Prague Metro (lines A, B, and C – its length is 65 km (40 mi) with 61 stations in total), Prague tram system, Prague buses, funiculars, and six ferries. Prague has one of the highest rates of public transport usage in the world, with 1.2 billion passenger journeys per year. Prague has about 130 bus lines (numbers 100–299) and 22 tram lines (numbers 1–26). There are also three funiculars, one on Petřín Hill, one on Mrázovka Hill and a third at the Zoo in Troja.

The Prague tram system now operates various types of trams: still popular classic Tatra T3, newer Tatra KT8D5, T6A5, Škoda 14 T (designed by Porsche), newest modern Škoda 15 T and nostalgic tram lines 23 and 41. Although Melbourne, Australia has the longest total tram system length in the world, Prague's tram network is one of the largest in the world by other measures.

The Prague tram rolling stock consists of over 900 individual cars, of those around 400 are the modernized T3 class, which are typically operated coupled together in pairs. The system carries more than 356 million passengers annually, the highest tram patronage in the world after Budapest. On a per capita basis, Prague has the second highest tram patronage after Zürich.

All services have a common ticketing system, and are run by the Prague Public Transport Company (Dopravní podnik hl. m. Prahy, a. s.) and several other companies. Recently, the Regional Organiser of Prague Integrated Transport (ROPID) has franchised operation of ferries on the Vltava river, which are also a part of the public transport system with common fares. Taxi services make pick-ups on the streets or operate from regulated taxi stands.

Prague Metro

The Metro has three major lines extending throughout the city: A (green), B (yellow) and C (red). A fourth Metro line is planned, which would connect the city centre to southern parts of the city.[72] The Prague Metro system served 589.2 million passengers in 2012,[73] making it the fifth busiest metro system in Europe and the most-patronised in the world on a per capita basis. The first section of the Prague metro was put into operation in 1974. It was the stretch between stations Kačerov and Florenc on the current line C. The first part of Line A was opened in 1978 (Dejvická – Náměstí Míru), the first part of line B in 1985 (Anděl – Florenc).

In April 2015, construction finished to extend the green line A further into the northwest corner of Prague closer to the airport.[74] A new interchange station for the bus in the direction of the airport is now the station Nádraží Veleslavín. The final station of the green line is Nemocnice Motol (Motol Hospital), giving people direct public transportation access to the largest medical facility in the Czech Republic and one of the largest in Europe. A railway connection to the airport is planned.

In operation there are currently two kinds of units: "81-71M" which is modernized variant of the Soviet 81-71 (completely modernized between 1995 and 2003) and new "Metro M1" trains (since 2000), manufactured by consortium consisting of Siemens, ČKD Praha and ADtranz. The minimum interval between two trains is 90 seconds.

The original Soviet vehicles "Ečs" were excluded in 1997, but one vehicle is placed in public transport museum in depot Střešovice.[75] The Náměstí Míru metro station is the deepest station and is equipped with the longest escalator in European Union. The Prague metro is generally considered very safe.

Roads

The main flow of traffic leads through the centre of the city and through inner and outer ring roads (partially in operation).

Inner Ring Road (The City Ring "MO"): Once completed it will surround the wider central part of the city. The longest city tunnel in Europe with a length of 5.5 kilometres (3.4 miles) and five interchanges has been completed to relieve congestion in the north-western part of Prague. Called Blanka tunnel complex and part of the City Ring Road, it was estimated to eventually cost – after several increases – 43 billion CZK. Construction started in 2007 and, after repeated delays, the tunnel was officially opened in September 2015. This tunnel complex completes a major part of the inner ring road. The entire City Ring is estimated to be finished after 2020.

Outer Ring Road (The Prague Ring "D0"): This ring road will connect all major motorways and speedways that meet each other in Prague region and provide faster transit without a necessity to drive through the city. So far 39 km (24 mi), out of a total planned 83 km (52 mi), is in operation. The year of full completion is unknown due to incompetent, constantly changing, leadership of Czech Road and Motorway Directorate, lack of administrative preparations, and insufficient funding of road constructions. Most recently, the southern part of this road (with a length of more than 20 km (12 mi)) was opened on 22 September 2010.[76]

Rail

The city forms the hub of the Czech railway system, with services to all parts of the country and abroad. The railway system links Prague with major European cities (which can be reached without transfers), including Berlin, Munich, Hamburg and Dresden (Germany); Vienna (Austria); Warsaw (Poland); Bratislava and Košice (Slovakia); Budapest (Hungary); Zürich (Switzerland); Split (Croatia); Belgrade (Serbia) and Moscow (Russia). Travel times range between 4.5 hours to Berlin and 27 hours to Moscow.[77]

Prague's main international railway station is Hlavní nádraží,[78] rail services are also available from other main stations: Masarykovo nádraží, Holešovice and Smíchov, in addition to suburban stations. Commuter rail services operate under the name Esko Praha, which is part of PID (Prague Integrated Transport).

Air

Prague is served by Václav Havel Airport, the largest airport in the Czech Republic and one of the largest airports in central and eastern Europe. The airport was named after the first Czech President, Vaclav Havel. Vaclav Havel was also the ninth and last president of Czechoslovakia.[79] The airport is the hub of the flag carrier, Czech Airlines,[80] as well as of the low-cost airlines SmartWings and Wizz Air operating throughout Europe. Other airports in Prague include the city's original airport in the north-eastern district of Kbely, which is serviced by the Czech Air Force, also internationally. The runway (9–27) at Kbely is 2 km (1 mi) long. The airport also houses the Prague Aviation Museum. The nearby Letňany airport is mainly used for private aviation and aeroclub aviation. Another airport in the proximity is Aero Vodochody aircraft factory to the north, used for testing purposes, as well as for aeroclub aviation. There are a few aeroclubs around Prague, such as the Točná airfield.

Sport

Prague is the site of many sports events, national stadiums and teams.

- Sparta Prague (Czech First League) – football club

- Slavia Prague (Czech First League) – football club

- Dukla Prague (Czech First League) – football club

- Bohemians 1905 (Czech First League) – football club

- Viktoria Žižkov (Czech 2. Liga) – football club

- HC Sparta Praha (Czech Extraliga) – ice hockey club

- HC Slavia Praha (1st Czech Republic Hockey League) – ice hockey club

- O2 Arena – the second largest ice hockey arena in Europe. It hosted 2004 and 2015 Ice Hockey World Championship, NHL 2008 and 2010 Opening Game and Euroleague Final Four

- Strahov Stadium – the largest stadium in the world

- Prague International Marathon

- Prague Open – Tennis Tournament held by the I. Czech Lawn Tennis Club

- Sparta Prague Open – Tennis Tournament held in Prague 7

- Josef Odložil Memorial – Athletics meeting

- Mystic SK8 Cup – World Cup of Skateboarding venue takes place at the Štvanice skatepark

- Gutovka – sport area with a large concrete skatepark, the highest outside climbing wall in Central Europe, four beach volleyball courts and children’s playground[81]

- World Ultimate Club Championships 2010[82]

International relations

The city of Prague maintains its own EU delegation in Brussels called Prague House.[83]

Prague was the location of U.S. President Barack Obama's speech on 5 April 2009, which led to the New START treaty with Russia, signed in Prague on 8 April 2010.[84]

The annual conference Forum 2000, which was founded by former Czech President Václav Havel, Japanese philanthropist Yōhei Sasakawa, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel in 1996, is held in Prague. Its main objective is "to identify the key issues facing civilization and to explore ways to prevent the escalation of conflicts that have religion, culture or ethnicity as their primary components", and also intends to promote democracy in non-democratic countries and to support civil society. Conferences have attracted a number of prominent thinkers, Nobel laureates, former and acting politicians, business leaders and other individuals like: Frederik Willem de Klerk, Bill Clinton, Nicholas Winton, Oscar Arias Sánchez, Dalai Lama, Hans Küng, Shimon Peres and Madeleine Albright.

Twin towns

Berlin, Germany

Berlin, Germany Bratislava, Slovakia

Bratislava, Slovakia.svg.png) Brussels, Belgium

Brussels, Belgium Budapest, Hungary

Budapest, Hungary Chicago, United States

Chicago, United States Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Frankfurt am Main, Germany Guangzhou, China

Guangzhou, China Hamburg, Germany

Hamburg, Germany Jerusalem, Israel

Jerusalem, Israel Kyoto, Japan

Kyoto, Japan Luxembourg, Luxembourg

Luxembourg, Luxembourg Miami-Dade, United States

Miami-Dade, United States Moscow, Russia

Moscow, Russia Nuremberg, Germany

Nuremberg, Germany Phoenix, United States

Phoenix, United States Riga, Latvia

Riga, Latvia Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, South Korea Shanghai, China

Shanghai, China Taipei, Taiwan

Taipei, Taiwan

Namesakes

A number of other settlements are derived or similar to the name of Prague. In many of these cases, Czech emigration has left a number of namesake cities scattered over the globe, with a notable concentration in the New World.

|

Additionally, Kłodzko is traditionally referred to as "Little Prague" (German: Klein-Prag). Although now in Poland, the city was the capital of the Bohemian kraj of the County of Kladsko.[89]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Václav Vojtíšek, Znak Hlavního Města Prahy / Les Armoires de la Ville de Prague (1928), cited after nakedtourguideprague.com (2015).

- ↑ Milan Ducháček, Václav Chaloupecký: Hledání československých dějin (2014), cited after abicko.avcr.cz.

- ↑ "Demographia World Urban Areas" (PDF). Demographia.com. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Nejnovější údaje o kraji" [Latest data on the region]. Regional Office of the Czech Statistical Office in the Capital City of Prague (in Czech). 17 October 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Van Ermengem, Kristiaan. "Prague Facts & Figures, Population". aviewoncities.com. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "Czech Republic Facts". World InfoZone. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Eurostat. "Urban Audit 2004". Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ↑ "Czech Republic". Worldatlas.com. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Short History of Bohemia, Moravia and then Czechoslovakia and Czech Republic". hedgie.eu. 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "Charles University Official Website".

- ↑ "The World According to GaWC 2016". GaWC.

- 1 2 "Best Destinations in the World – Travelers' Choice Awards – TripAdvisor". tripadvisor.com. 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- 1 2 Bremner, Caroline (2016). "Top 100 City Destinations Ranking". Euromonitor International. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Demetz, Peter (1997). "Chapter One: Libussa, or Versions of Origin". Prague in Black and Gold: Scenes from the Life of a European City. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-7843-0. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Kenety, Brian. "Unearthing Bohemia's Celtic heritage ahead of Samhain, the 'New Year'". Czech Radio.

- ↑ Kenety, Brian. "Atlantis české archeologie" (in Czech). Czech Radio.

- 1 2 Dovid Solomon Ganz, Tzemach Dovid (3rd edition), part 2, Warsaw 1878, p. 71, 85 (available online )

- ↑ "Praha byla Casurgis" [Prague was Casurgis] (in Czech). cs-magazin.com. February 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "Slované na Hradě žili už sto let před Bořivojem –". Novinky.cz. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "Archaeological Research – Prague Castle". Hrad.cz. 8 July 2005. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "TOP MONUMENTS – VYŠEHRAD". praguewelcome.cz. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ↑ "The Cambridge Economic History of Europe: Trade and industry in the Middle Ages". Michael Moïssey Postan, Edward Miller, Cynthia Postan (1987). Cambridge University Press. p. 417. ISBN 0-521-08709-0.

- ↑ Stone, Andrew. A Hedonist's Guide to New York.

- ↑ "The Prague Pogrom of 1389". Everything2. April 1389. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ "The former Jewish Quarter in Prague". prague.cz. April 1389. Retrieved 16 June 2009.

- ↑ This swallow-tailed banner is approximately 4 by 6 feet (1.2 by 1.8 metres), with a red field sprinkled with small white fleurs-de-lis, and a silver old Town Coat-of-Arms in the centre. The words PÁN BŮH POMOC NAŠE (The Lord God is our Help) appeared above the coat-of-arms, with a Hussite "host with chalice" centred on the top. Near the swallow-tails is a crescent shaped golden sun with rays protruding. One of these banners was captured by Swedish troops in Battle of Prague (1648), when they captured the western bank of the Vltava river and were repulsed from the eastern bank, they placed it in the Royal Military Museum in Stockholm; although this flag still exists, it is in very poor condition. They also took the Codex Gigas and the Codex Argenteus. The earliest evidence indicates that a gonfalon with a municipal charge painted on it was used for Old Town as early as 1419. Since this city militia flag was in use before 1477 and during the Hussite Wars, it is the oldest still preserved municipal flag of Bohemia.

- ↑ "Architecture of the Gothic". Old.hrad.cz. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Old Royal Palace with Vladislav Hall – Prague Castle". Hrad.cz. 16 December 2011. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Religious conflicts". Prague.st. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "The Kingdom of Bohemia during the Thirty Years' War". Family-lines.cz. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "Prague". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ M. Signoli, D. Chevé, A. Pascal (2007)."Plague epidemics in Czech countries". p.51.

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Prague". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–250.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Prague". Encyclopædia Britannica. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 248–250. - ↑ "Looking Back at the Bombing of Prague". The Prague Post. 14 February 1945. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ↑ "Prague Assembly Confirms 2016 Olympic Bid". Gamesbids.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "It's Official – Prague Out of 2020 Bid". GamesBids. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "What's in a name? Prague History lesson". praguesummer.com. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Lucy S. Dawidowicz – The Golden Tradition: Jewish Life and Thought in Eastern Europe 1996 p. 351 "Then you surely knew also Reb Shmuel on the other side of the Vistula, in Praga! Praga, the threshold of Warsaw—the aroma of the country, with its broad fields, so many times desolated by wars and fires and rebuilt, ..."

- ↑ "drexler blog". Drexler, novinky.cz. 11 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 October 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ↑ "Kolik věží má "stověžatá" Praha? Nadšenci jich napočítali přes pět set". idnes.cz (in Czech). Mladá fronta DNES. 5 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- ↑ "Visit Prague, the City of a Hundred spires.". prague.fm. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ "Basic Prague and Czech Republic Info". prague.cz. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Latitude and Longitude of World Cities: Frankfurt". Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Latitude and Longitude of World Cities". Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Latitude and Longitude of Vancouver, Canada". Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Census shows population rise in Prague". Prague Daily Monitor. Czech News Agency (ČTK). 24 January 2012. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Historický lexikon obcí České republiky 1869–2005

- ↑ "Pohyb obyvatelstva v Českých zemích" (in Czech). Czso.cz. 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ "Počet obyvatel v obcích České republiky k 1.1.2013" (in Czech). 1 January 2013. Archived from the original (XLS) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ "Cizinci 3. zemí se zaevidovaným povoleným pobytem na území České republiky a cizinci zemí EU + Islandu, Norska, Švýcarska a Lichtenštejnska se zaevidovaným pobytem na území České republiky k 30. 11. 2016". Ministry of the Interior. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ "The Climate of Prague 1981–2010 (Temperatures, Humidity)" (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ "Praha Climate Normals 1961–1990 (Precipitation, Precipitation days, Snow, Sunhours)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Lubor Mrazek. "O SLAVNOSTECH, Letní shakespearovské slavnosti 2013, Agentura SCHOK, Praha". Shakespeare.cz. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Prague Studios Credits: Movies shot at Prague Studios". Prague Studios. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Forbes Magazine: Prague Zoo the 7th Best in the World". Abcprague.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- 1 2 "Prague Strategic Plan, 2008 Update" (PDF). Official site. City Development Authority Prague. 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- 1 2 "Regional GDP per inhabitant in 2007" (PDF). Official site. Eurostat. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2010.

- ↑ "Prague has highest average monthly salary at CZK 35,853".

- ↑ Hold, Gabriella (21 April 2010). "Foreign Resident Numbers Stable". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Contiguglia, Cat (13 October 2010). "Prague Is Best CEE City for Business – Survey". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "EIU Media Directory". Eiuresources.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "2thinknow Innovation Cities Top 100 Index". 2thinknow Innovation Cities Program. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

- ↑ "Nejdražší ulice ve střední Evropě? Bezkonkurenčně vedou Příkopy". Mladá fronta DNES. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Pop, Valentina (18 February 2010). "EUobserver / Prague Outranks Paris and Stockholm Among EU's Richest Regions". EUobserver. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ "ESTAT-2002-05354-00-00-EN-TRA-00 (FR)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- ↑ Filipová, Hana (11 October 2015). "Které firmy vládnou krajům? Týdeník Ekonom zmapoval podnikání v regionech" [Which firms dominate the regions? 'The Weekly Ekonom' mapped out entrepreneurship in the regions] (in Czech). Economics news. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑

- ↑ "Pros and Cons of Moving to Czech Republic". ExpatArrivals.

- ↑ "Kampa Island". YourCzechRepublic.cz. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ↑ "Vinohrady sights". myCzechRepublic.

- ↑ J. Pechlát (2010)."Prague as a knowledge city-region" In: Teorie vědy, XXXI/3-4 2009, The Institute of Philosophy of the AS CR, p. 247-267.

- ↑ "Prague Metro, Czech Republic". railwaytechnology.com. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2012" (PDF). Public Transport Company of the Capital City of Prague. 2012. p. 66. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Hold, Gabriella (30 June 2010). "Metro Extension on the Right Track". The Prague Post. Czech Republic. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "Historická souprava Ečs". Metroweb.cz. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ↑ "Opening of Prague's Outer Ring (Czech only)". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 18 Dec 2014.

- ↑ "České dráhy". Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ↑ "Czech Transport". Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ↑ "Václav Havel". Wikipedie (in Czech). 2016-12-10.

- ↑ "Czech Airlines: Company Info". Czech Airlines. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "Gutovka". Praha.eu. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- ↑ "Prague, Czech Republic to host the WFDF World Ultimate Club Championships 2010". WFDF. Retrieved 10 September 2008.

- ↑ "Prague House: Mission and representational activities". prague-house.eu. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ Ratification of the START treaty is a step towards Obama's goal of a nuclear weapons-free world. (Official White House Photo) by Pete Souza Dec. 2010.

- ↑ "| Texas State Historical Association (TSHA)". Tshaonline.org. 10 November 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "The History of Prague". cityofpragueok.org. 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "CASDE | Prague – Saunders County". Casde.unl.edu. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Visitor Information". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Klodzko: Dolnośląskie – Poland". International Jewish Cemetery Project. 24 October 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

Further reading

- Jekova, Alena. 77 Prague Legends. Prague: Prah, 2006. ISBN 80-7252-139-X

- Prague Legends (Think Prague Magazine) (2002) Legend's of Prague

- Prague (Eyewitness Travel Guide by DK Publishing) (2009) excerpt and text search 2006 edition

- Prague (City Guide) by Neil Wilson (2009) excerpt and text search

- Praha – Prague and environs (by Čedok) (1926) city guide from 1920s

- Rick Steves' Prague and The Czech Republic by Rick Steves and Honza Vihan (2009) excerpt and text search

- Wilson, Neil. Lonely Planet Prague (2007) excerpt and text search

- Wilson, Paul. Prague: A Traveler's Literary Companion (1995)

- Prague Top 10 (2011) Prague Top 10

Culture and society

- Becker, Edwin et al., ed. Prague 1900: Poetry and Ecstasy. (2000). 224 pp.

- Boehm, Barbara Drake; et al. (2005). Prague : the Crown of Bohemia, 1347-1437. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 1588391612.

- Burton, Richard D. E. Prague: A Cultural and Literary History. (2003). 268 pp. excerpt and text search

- Cohen, Gary B. The Politics of Ethnic Survival: Germans in Prague, 1861–1914. (1981). 344 pp.

- Fucíková, Eliska, ed. Rudolf II and Prague: The Court and the City. (1997). 792 pp.

- Holz, Keith. Modern German Art for Thirties Paris, Prague, and London: Resistance and Acquiescence in a Democratic Public Sphere. (2004). 359 pp.

- Iggers, Wilma Abeles. Women of Prague: Ethnic Diversity and Social Change from the Eighteenth Century to the Present. (1995). 381 pp. online edition

- Kleineberg, A., Marx, Ch., Knobloch, E., Lelgemann, D.: Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios`"Atlas der Oikumene". WBG 2010. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9.

- Porizka, Lubomir; Hojda, Zdenek; and Pesek, Jirí. The Palaces of Prague. (1995). 216 pp.

- Sayer, Derek. Prague, Capital of the Twentieth Century: A Surrealist History (Princeton University Press; 2013) 595 pages; a study of the city as a crossroads for modernity.

- Sayer, Derek. "The Language of Nationality and the Nationality of Language: Prague 1780–1920." Past & Present 1996 (153): 164–210. in Jstor

- Spector, Scott. Prague Territories: National Conflict and Cultural Innovation in Kafka's Fin de Siècle. (2000). 331 pp. online edition

- Svácha, Rostislav. The Architecture of New Prague, 1895–1945. (1995). 573 pp.

- Wittlich, Peter. Prague: Fin de Siècle. (1992). 280 pp.

External links

| Look up prague in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Official Tourist Website for Prague

Media related to Praha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Praha at Wikimedia Commons Prague travel guide from Wikivoyage

Prague travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Atlas of Europe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Atlas of Europe at Wikimedia Commons