Power amplifier classes

Power amplifier classes are, in electronics, a letter symbol applied to different types of power amplifier. The amplifier classes give a broad indication of the characteristics and performance of different types of amplifier. The classes are related to the time period that the active amplifier device is passing current, expressed as a fraction of the period of a signal waveform applied to the input. A class A amplifier is conducting all though the period of each signal; Class B only for one-half the input period, class C for much less than half the input period. A Class D amplifier operates its output device in a switching manner; the fraction of the time that the device is conducting is adjusted so a pulse width modulation output is obtained from the stage.

Additional letter classes are defined for special purpose amplifiers, with additional active elements or particular power supply improvements; sometimes a new letter symbol is used by a manufacturer to promote its proprietary design.

Power amplifier classes

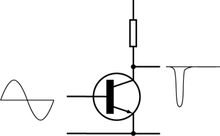

Power amplifier circuits (output stages) are classified as A, B, AB and C for analog designs—and class D and E for switching designs. The classes are based on the proportion of each input cycle (conduction angle) during which an amplifying device passes current.[1] The image of the conduction angle derives from amplifying a sinusoidal signal. If the device is always on, the conducting angle is 360°. If it is on for only half of each cycle, the angle is 180°. The angle of flow is closely related to the amplifier power efficiency.

In the illustrations below, a bipolar junction transistor is shown as the amplifying device. However the same attributes are found with MOSFETs or vacuum tubes.

Class A

In a Class A amplifier, 100% of the input signal is used (conduction angle Θ = 360°). The active element remains conducting[2] all of the time.

Amplifying devices operating in class A conduct over the entire range of the input cycle. A class-A amplifier is distinguished by the output stage devices being biased for class A operation. Subclass A2 is sometimes used to refer to vacuum-tube class-A stages that drive the grid slightly positive on signal peaks for slightly more power than normal class A (A1; where the grid is always negative[3][4]). This, however, incurs higher signal distortion.

Advantages of class-A amplifiers

- Class-A designs can be simpler than other classes insofar as class -AB and -B designs require two connected devices in the circuit (push–pull output), each to handle one half of the waveform whereas class A can use a single device (single-ended).

- The amplifying element is biased so the device is always conducting, the quiescent (small-signal) collector current (for transistors; drain current for FETs or anode/plate current for vacuum tubes) is close to the most linear portion of its transconductance curve.

- Because the device is never 'off' there is no "turn on" time, no problems with charge storage, and generally better high frequency performance and feedback loop stability (and usually fewer high-order harmonics).

- The point where the device comes closest to being 'off' is not at 'zero signal', so the problems of crossover distortion associated with class-AB and -B designs is avoided.

- Best for low signal levels of radio receivers due to low distortion.

Disadvantage of class-A amplifiers

- Class-A amplifiers are inefficient. A maximum theoretical efficiency of 25% is obtainable using usual configurations, but 50% is the maximum for a transformer or inductively coupled configuration.[5] In a power amplifier, this not only wastes power and limits operation with batteries, but increases operating costs and requires higher-rated output devices. Inefficiency comes from the standing current that must be roughly half the maximum output current, and a large part of the power supply voltage is present across the output device at low signal levels. If high output power is needed from a class-A circuit, the power supply and accompanying heat becomes significant. For every watt delivered to the load, the amplifier itself, at best, uses an extra watt. For high power amplifiers this means very large and expensive power supplies and heat sinks.

Class-A power amplifier designs have largely been superseded by more efficient designs, though their simplicity makes them popular with some hobbyists. There is a market for expensive high fidelity class-A amps considered a "cult item" among audiophiles[6] mainly for their absence of crossover distortion and reduced odd-harmonic and high-order harmonic distortion. Class A power amps are also used in some "boutique" guitar amplifiers due to their perceived tonal qualities.

Single-ended and triode class-A amplifiers

Some hobbyists who prefer class-A amplifiers also prefer the use of thermionic valve (tube) designs instead of transistors, for several reasons:

- Single-ended output stages have an asymmetrical transfer function, meaning that even-order harmonics in the created distortion tend to not cancel out (as they do in push–pull output stages). For tubes, or FETs, most distortion is second-order harmonics, from the square law transfer characteristic, which to some produces a "warmer" and more pleasant sound.[7][8]

- For those who prefer low distortion figures, the use of tubes with class A (generating little odd-harmonic distortion, as mentioned above) together with symmetrical circuits (such as push–pull output stages, or balanced low-level stages) results in the cancellation of most of the even distortion harmonics, hence the removal of most of the distortion.

- Historically, valve amplifiers were often used a class-A power amplifier simply because valves are large and expensive; many class-A designs use only a single device.

Transistors are much cheaper, and so more elaborate designs that give greater efficiency but use more parts are still cost-effective. A classic application for a pair of class-A devices is the long-tailed pair, which is exceptionally linear, and forms the basis of many more complex circuits, including many audio amplifiers and almost all op-amps.

Class-A amplifiers may be used in output stages of op-amps[9] (although the accuracy of the bias in low cost op-amps such as the 741 may result in class A or class AB or class B performance, varying from device to device or with temperature). They are sometimes used as medium-power, low-efficiency, and high-cost audio power amplifiers. The power consumption is unrelated to the output power. At idle (no input), the power consumption is essentially the same as at high output volume. The result is low efficiency and high heat dissipation.

Class B

In a class-B amplifier, the active device conducts for 180 degrees of the cycle. This would cause intolerable distortion, so two devices are used, each conducts for one half (180°) of the signal cycle, and the device currents are combined so that the load current is continuous.[10]

At radio frequency, if the load of the class-B amplifier is a tuned circuit, a single device in class B can be used. These are used in linear amplifiers, so called because the radio frequency output power is proportional to the square of the input excitation voltage. This characteristic prevents distortion of amplitude-modulated or frequency-modulated signals passing through the amplifier. Such amplifiers have an efficiency around 60%.[11]

Class-B amplifiers amplify the signal with two active devices, each operating over one half of the cycle. Efficiency is much improved over class-A amplifiers.[12] Class-B amplifiers are also favoured in battery-operated devices, such as transistor radios. Class B has a maximum theoretical efficiency of π/4 (≈ 78.5%).[13]

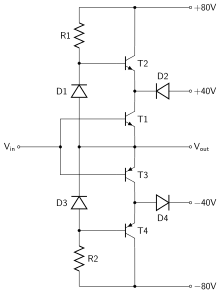

A practical circuit using class-B elements is the push–pull stage, such as the very simplified complementary pair arrangement shown at right. Complementary devices are each used for amplifying the opposite halves of the input signal, which is then recombined at the output. This arrangement gives good efficiency, but usually suffers from the drawback that there is a small mismatch in the cross-over region – at the "joins" between the two halves of the signal, as one output device has to take over supplying power exactly as the other finishes. This is called crossover distortion. An improvement is to bias the devices so they are not completely off when they are not in use. This approach is called class AB operation.

Class AB

In a class-AB amplifier, the conduction angle is intermediate between class A and B; the two active elements conduct more than half of the time. Class AB is widely considered a good compromise for amplifiers, since much of the time the music signal is quiet enough that the signal stays in the "class-A" region, where it is amplified with good fidelity, and by definition if passing out of this region, is large enough that the distortion products typical of class B are relatively small. The crossover distortion can be reduced further by using negative feedback.

In class-AB operation, each device operates the same way as in class B over half the waveform, but also conducts a small amount on the other half.[14] As a result, the region where both devices simultaneously are nearly off (the "dead zone") is reduced. The result is that when the waveforms from the two devices are combined, the crossover is greatly minimised or eliminated altogether. The exact choice of quiescent current (the standing current through both devices when there is no signal) makes a large difference to the level of distortion (and to the risk of thermal runaway, that may damage the devices). Often, bias voltage applied to set this quiescent current must be adjusted with the temperature of the output transistors. (For example, in the circuit at the beginning of the article, the diodes would be mounted physically close to the output transistors, and specified to have a matched temperature coefficient.) Another approach (often used with thermally tracking bias voltages) is to include small value resistors in series with the emitters.

Class AB sacrifices some efficiency over class B in favor of linearity, thus is less efficient (below 78.5% for full-amplitude sine waves in transistor amplifiers, typically; much less is common in class-AB vacuum-tube amplifiers). It is typically much more efficient than class A.

Sometimes a numeral is added for vacuum-tube stages. If grid current is not permitted to flow, the class is AB1. If grid current is allowed to flow (adding more distortion, but giving slightly higher output power) the class is AB2.[4]

Class C

In a class-C amplifier, less than 50% of the input signal is used (conduction angle Θ < 180°). Distortion is high and practical use requires a tuned circuit as load. Efficiency can reach 80% in radio-frequency applications.[11]

The usual application for class-C amplifiers is in RF transmitters operating at a single fixed carrier frequency, where the distortion is controlled by a tuned load on the amplifier. The input signal is used to switch the active device causing pulses of current to flow through a tuned circuit forming part of the load.[15]

The class-C amplifier has two modes of operation: tuned and untuned.[16] The diagram shows a waveform from a simple class-C circuit without the tuned load. This is called untuned operation, and the analysis of the waveforms shows the massive distortion that appears in the signal. When the proper load (e.g., an inductive-capacitive filter plus a load resistor) is used, two things happen. The first is that the output's bias level is clamped with the average output voltage equal to the supply voltage. This is why tuned operation is sometimes called a clamper. This restores the waveform to its proper shape, despite the amplifier having only a one-polarity supply. This is directly related to the second phenomenon: the waveform on the center frequency becomes less distorted. The residual distortion is dependent upon the bandwidth of the tuned load, with the center frequency seeing very little distortion, but greater attenuation the farther from the tuned frequency that the signal gets.

The tuned circuit resonates at one frequency, the fixed carrier frequency, and so the unwanted frequencies are suppressed, and the wanted full signal (sine wave) is extracted by the tuned load. The signal bandwidth of the amplifier is limited by the Q-factor of the tuned circuit but this is not a serious limitation. Any residual harmonics can be removed using a further filter.

In practical class-C amplifiers a tuned load is invariably used. In one common arrangement the resistor shown in the circuit above is replaced with a parallel-tuned circuit consisting of an inductor and capacitor in parallel, whose components are chosen to resonate the frequency of the input signal. Power can be coupled to a load by transformer action with a secondary coil wound on the inductor. The average voltage at the collector is then equal to the supply voltage, and the signal voltage appearing across the tuned circuit varies from near zero to near twice the supply voltage during the RF cycle. The input circuit is biased so that the active element (e.g., transistor) conducts for only a fraction of the RF cycle, usually one third (120 degrees) or less.[17]

The active element conducts only while the collector voltage is passing through its minimum. By this means, power dissipation in the active device is minimised, and efficiency increased. Ideally, the active element would pass only an instantaneous current pulse while the voltage across it is zero: it then dissipates no power and 100% efficiency is achieved. However practical devices have a limit to the peak current they can pass, and the pulse must therefore be widened, to around 120 degrees, to obtain a reasonable amount of power, and the efficiency is then 60–70%.[17]

Class D

Class-D amplifiers use some form of pulse-width modulation to control the output devices. The conduction angle of each device is no longer related directly to the input signal but instead varies in pulse width.

In the class-D amplifier the active devices (transistors) function as electronic switches instead of linear gain devices; they are either on or off. The analog signal is converted to a stream of pulses that represents the signal by pulse-width modulation, pulse-density modulation, delta-sigma modulation or a related modulation technique before being applied to the amplifier. The time average power value of the pulses is directly proportional to the analog signal, so after amplification the signal can be converted back to an analog signal by a passive low-pass filter. The purpose of the output filter is to smooth the pulse stream to an analog signal, removing the high frequency spectral components of the pulses. The frequency of the output pulses is typically ten or more times the highest frequency in the input signal to amplify, so that the filter can adequately reduce the unwanted harmonics and accurately reproduce the input.[18]

The main advantage of a class-D amplifier is power efficiency. Because the output pulses have a fixed amplitude, the switching elements (usually MOSFETs, but vacuum tubes, and at one time bipolar transistors, were used) are switched either completely on or completely off, rather than operated in linear mode. A MOSFET operates with the lowest resistance when fully on and thus (excluding when fully off) has the lowest power dissipation when in that condition. Compared to an equivalent class-AB device, a class-D amplifier's lower losses permit the use of a smaller heat sink for the MOSFETs while also reducing the amount of input power required, allowing for a lower-capacity power supply design. Therefore, class-D amplifiers are typically smaller than an equivalent class-AB amplifier.

Another advantage of the class-D amplifier is that it can operate from a digital signal source without requiring a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) to convert the signal to analog form first. If the signal source is in digital form, such as in a digital media player or computer sound card, the digital circuitry can convert the binary digital signal directly to a pulse-width modulation signal that is applied to the amplifier, simplifying the circuitry considerably.

Class-D amplifiers are widely used to control motors—but are now also used as power amplifiers, with extra circuitry that converts analogue to a much higher frequency pulse width modulated signal. Switching power supplies have even been modified into crude class-D amplifiers (though typically these only reproduce low-frequencies with acceptable accuracy).

High quality class-D audio power amplifiers have now appeared on the market. These designs have been said to rival traditional AB amplifiers in terms of quality. An early use of class-D amplifiers was high-power subwoofer amplifiers in cars. Because subwoofers are generally limited to a bandwidth of no higher than 150 Hz, switching speed for the amplifier does not have to be as high as for a full range amplifier, allowing simpler designs. Class-D amplifiers for driving subwoofers are relatively inexpensive in comparison to class-AB amplifiers.

The letter D used to designate this amplifier class is simply the next letter after C and, although occasionally used as such, does not stand for digital. Class-D and class-E amplifiers are sometimes mistakenly described as "digital" because the output waveform superficially resembles a pulse-train of digital symbols, but a class-D amplifier merely converts an input waveform into a continuously pulse-width modulated analog signal. (A digital waveform would be pulse-code modulated.)

Additional classes

Other amplifier classes are mainly variations of the previous classes. For example, class-G and class-H amplifiers are marked by variation of the supply rails (in discrete steps or in a continuous fashion, respectively) following the input signal. Wasted heat on the output devices can be reduced as excess voltage is kept to a minimum. The amplifier that is fed with these rails itself can be of any class. These kinds of amplifiers are more complex, and are mainly used for specialized applications, such as very high-power units. Also, class-E and class-F amplifiers are commonly described in literature for radio-frequency applications where efficiency of the traditional classes is important, yet several aspects deviate substantially from their ideal values. These classes use harmonic tuning of their output networks to achieve higher efficiency and can be considered a subset of class C due to their conduction-angle characteristics.

Class E

The class-E/F amplifier is a highly efficient switching power amplifier, typically used at such high frequencies that the switching time becomes comparable to the duty time. As said in the class-D amplifier, the transistor is connected via a serial LC circuit to the load, and connected via a large L (inductor) to the supply voltage. The supply voltage is connected to ground via a large capacitor to prevent any RF signals leaking into the supply. The class-E amplifier adds a C (capacitor) between the transistor and ground and uses a defined L1 to connect to the supply voltage.

The following description ignores DC, which can be added easily afterwards. The above-mentioned C and L are in effect a parallel LC circuit to ground. When the transistor is on, it pushes through the serial LC circuit into the load and some current begins to flow to the parallel LC circuit to ground. Then the serial LC circuit swings back and compensates the current into the parallel LC circuit. At this point the current through the transistor is zero and it is switched off. Both LC circuits are now filled with energy in C and L0. The whole circuit performs a damped oscillation. The damping by the load has been adjusted so that some time later the energy from the Ls is gone into the load, but the energy in both C0 peaks at the original value to in turn restore the original voltage so that the voltage across the transistor is zero again and it can be switched on.

With load, frequency, and duty cycle (0.5) as given parameters and the constraint that the voltage is not only restored, but peaks at the original voltage, the four parameters (L, L0, C and C0) are determined. The class-E amplifier takes the finite on resistance into account and tries to make the current touch the bottom at zero. This means that the voltage and the current at the transistor are symmetric with respect to time. The Fourier transform allows an elegant formulation to generate the complicated LC networks and says that the first harmonic is passed into the load, all even harmonics are shorted and all higher odd harmonics are open.

Class E uses a significant amount of second-harmonic voltage. The second harmonic can be used to reduce the overlap with edges with finite sharpness. For this to work, energy on the second harmonic has to flow from the load into the transistor, and no source for this is visible in the circuit diagram. In reality, the impedance is mostly reactive and the only reason for it is that class E is a class F (see below) amplifier with a much simplified load network and thus has to deal with imperfections.

In many amateur simulations of class-E amplifiers, sharp current edges are assumed nullifying the very motivation for class E and measurements near the transit frequency of the transistors show very symmetric curves, which look much similar to class-F simulations.

The class-E amplifier was invented in 1972 by Nathan O. Sokal and Alan D. Sokal, and details were first published in 1975.[19] Some earlier reports on this operating class have been published in Russian and Polish.

Class F

In push–pull amplifiers and in CMOS, the even harmonics of both transistors just cancel. Experiment shows that a square wave can be generated by those amplifiers. Theoretically square waves consist of odd harmonics only. In a class-D amplifier, the output filter blocks all harmonics; i.e., the harmonics see an open load. So even small currents in the harmonics suffice to generate a voltage square wave. The current is in phase with the voltage applied to the filter, but the voltage across the transistors is out of phase. Therefore, there is a minimal overlap between current through the transistors and voltage across the transistors. The sharper the edges, the lower the overlap.

While in class D, transistors and the load exist as two separate modules, class F admits imperfections like the parasitics of the transistor and tries to optimise the global system to have a high impedance at the harmonics. Of course there must be a finite voltage across the transistor to push the current across the on-state resistance. Because the combined current through both transistors is mostly in the first harmonic, it looks like a sine. That means that in the middle of the square the maximum of current has to flow, so it may make sense to have a dip in the square or in other words to allow some overswing of the voltage square wave. A class-F load network by definition has to transmit below a cutoff frequency and reflect above.

Any frequency lying below the cutoff and having its second harmonic above the cutoff can be amplified, that is an octave bandwidth. On the other hand, an inductive-capacitive series circuit with a large inductance and a tunable capacitance may be simpler to implement. By reducing the duty cycle below 0.5, the output amplitude can be modulated. The voltage square waveform degrades, but any overheating is compensated by the lower overall power flowing. Any load mismatch behind the filter can only act on the first harmonic current waveform, clearly only a purely resistive load makes sense, then the lower the resistance, the higher the current.

Class F can be driven by sine or by a square wave, for a sine the input can be tuned by an inductor to increase gain. If class F is implemented with a single transistor, the filter is complicated to short the even harmonics. All previous designs use sharp edges to minimise the overlap.

Classes G and H

There is a variety of amplifier designs that enhance class-AB output stages with more efficient techniques to achieve greater efficiency with low distortion. These designs are common in large audio amplifiers since the heatsinks and power transformers would be prohibitively large (and costly) without the efficiency increases. The terms "class G" and "class H" are used interchangeably to refer to different designs, varying in definition from one manufacturer or paper to another.

Class-G amplifiers (which use "rail switching" to decrease power consumption and increase efficiency) are more efficient than class-AB amplifiers. These amplifiers provide several power rails at different voltages and switch between them as the signal output approaches each level. Thus, the amplifier increases efficiency by reducing the wasted power at the output transistors. Class-G amplifiers are more efficient than class AB but less efficient when compared to class D, however, they do not have the electromagnetic interference effects of class D.

Class-H amplifiers take the idea of class G one step further creating an infinitely variable supply rail. This is done by modulating the supply rails so that the rails are only a few volts larger than the output signal at any given time. The output stage operates at its maximum efficiency all the time. Switched-mode power supplies can be used to create the tracking rails. Significant efficiency gains can be achieved but with the drawback of more complicated supply design and reduced THD performance. In common designs, a voltage drop of about 10V is maintained over the output transistors in Class H circuits. The picture above shows positive supply voltage of the output stage and the voltage at the speaker output. The boost of the supply voltage is shown for a real music signal.

See also

References

- ↑ "Understanding Amplifier Operating "Classes"". electronicdesign.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ RCA Receiving Tube Manual, RC-14 (1940) p 12

- ↑ ARRL Handbook, 1968; page 65

- 1 2 "Amplifier classes". www.duncanamps.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ [whites.sdsmt.edu/classes/ee322/class_notes/322Lecture18.pdf EE 332 Class Notes Lecture 18: Common Emitter Amplifier. Maximum Efficiency of Class A Amplifiers. Transformer Coupled Loads.]

- ↑ Jerry Del Colliano (20 February 2012), Pass Labs XA30.5 Class-A Stereo Amp Reviewed, Home Theater Review, Luxury Publishing Group Inc.

- ↑ Ask the Doctors: Tube vs. Solid-State Harmonics

- ↑ Volume cranked up in amp debate

- ↑ "Biasing Op-Amps into Class A". tangentsoft.net. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ Circuit Cellar - Amplifier classes from a to h

- 1 2 Larry Wolfgang, Charles Hutchinson (ed), The ARRL Handbook for Radio Amateurs, Sixty-Eighth Edition (1991), American Radio Relay League, 1990, ISBN 0-87259-168-9, pages 3-17, 5-6,

- ↑ "Class B Amplifier - Class-B Transistor Amplifier Electronic Amplifier Tutorial". Basic Electronics Tutorials. 2013-07-25. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ Tuite, Don (March 21, 2012). "Understanding Amplifier Classes". Electronic Design (March, 2012).

- ↑ "Class AB Power Amplifiers". www.learnabout-electronics.org. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ "Class C power amplifier circuit diagram and theory. Output characteristics DC load line". www.circuitstoday.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ A.P. Malvino, Electronic Principles (2nd Ed.1979. ISBN 0-07-039867-4) p.299.

- 1 2 Electronic and Radio Engineering, R.P.Terman, McGraw Hill, 1964

- ↑ "Class D Amplifiers: Fundamentals of Operation and Recent Developments - Application Note - Maxim". www.maximintegrated.com. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- ↑ N. O. Sokal and A. D. Sokal, "Class E – A New Class of High-Efficiency Tuned Single-Ended Switching Power Amplifiers", IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, vol. SC-10, pp. 168–176, June 1975. HVK