Quebec Bridge

| Quebec Bridge Pont de Québec | |

|---|---|

The Quebec bridge from the west side. | |

| Coordinates | 46°44′46″N 71°17′16″W / 46.74611°N 71.28778°W |

| Carries |

Route 175 Canadian National Railway and Via Rail 1 pedestrian walkway |

| Crosses | St. Lawrence River |

| Locale | Quebec City, and Lévis, Quebec |

| Maintained by | Canadian National Railway |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cantilever bridge |

| Total length | 987 m (3,238 ft) |

| Width | 29 m (95 ft) wide |

| Longest span | 549 m (1,801 ft) |

| Clearance above | (?) |

| Clearance below | (?) |

| No. of lanes | 3 |

| Rail characteristics | |

| No. of tracks | 2 |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Structure gauge | AAR |

| Electrified | No |

| History | |

| Opened | December 3, 1919 |

| Statistics | |

| Toll | none since 1942 |

| Designated | 1995 |

The Quebec Bridge (Pont de Québec in French) is a road, rail and pedestrian bridge across the lower Saint Lawrence River between Sainte-Foy (since 2002 a western suburb of Quebec City) and Lévis, Quebec, Canada. The project failed twice, at the cost of 88 lives, and took over 30 years to complete.

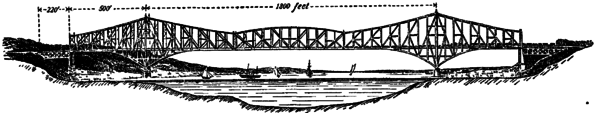

The Quebec Bridge is a riveted steel truss structure and is 987 m (3,238 ft) long, 29 m (95 ft) wide, and 104 m (341 ft) high. Cantilever arms 177 m (581 ft) long support a 195 m (640 ft) central structure, for a total span of 549 m (1,801 ft), still the longest cantilever bridge span in the world. (It was the all-categories longest span in the world until the Ambassador Bridge was completed in 1929.) It is the easternmost (farthest downstream) complete crossing of the Saint Lawrence.

The bridge accommodates three highway lanes (none until 1929, one until 1949, two until 1993), one rail line (two until 1949), and a pedestrian walkway (originally two); at one time it also carried a streetcar line. It has been owned by the Canadian National Railway since 1993.

The Quebec Bridge was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1995.[1]

Background

Before the Quebec Bridge was built, the only way to travel from the south shore of the St. Lawrence in Lévis to the north shore at Quebec City was to take a ferry or use the winter-time ice bridge. As far back as 1852 a project for a bridge over the St. Lawrence River at Quebec was considered, and again, in 1867, 1882, and 1884. After a period of political instability, through which Canada had four Prime Ministers in five years, Wilfrid Laurier, Member of Parliament for the federal riding of Quebec East, was elected on a Liberal platform in 1896, and was to spearhead the first Quebec bridge until he left office in 1911.

A March 1897 article in the Quebec Morning Chronicle noted:

The bridge question has again been revived after many years of slumber, and business men in Quebec seem hopeful that something will come of it, though the placing of a subsidy on the statute book is but a small part of the work to be accomplished, as some of its enthusiastic promoters will, ere long, discover. Both Federal and Provincial Governments seem disposed to contribute towards the cost, and the City of Quebec will also be expected to do its share. Many of our people have objected to any contribution being given by the city unless the bridge is built opposite the town, and the CHRONICLE like every other good citizen of Quebec would prefer to see it constructed at Diamond Harbor, and has contended in the interests of the city for this site as long as there seemed to be any possibility of securing it there. It would still do so if it appeared that our people could have it at that site. A bridge at Diamond Harbor would, it estimated, cost at least eight millions. It would be very nice to have, with its double track, electric car track, and roads for vehicles and pedestrians, and would no doubt create a goodly traffic between the two towns, and be one of the show works of the continent.

First design and collapse of August 29, 1907

The Quebec Bridge was included in the National Transcontinental Railway project, undertaken by the federal government. The Quebec Bridge Company was first incorporated by Act of Parliament under the government of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1887,[2] later revived in 1891,[3] once again revived for good in 1897 by the government of Wilfrid Laurier,[4] who granted them an extension of time in 1900.[5] In 1903, the bond issue was increased to $6,000,000 and power to grant preference shares was authorised, along with a name change to the Quebec Bridge and Railway Company (QBRC).[6] An Act of Parliament the same year was necessary to guarantee the bonds by the public purse.[7] Laurier was MP for Quebec East riding, while the president of the QBRC, Simon-Napoleon Parent, simultaneously was Premier of Quebec from 1900 to 1905, and was Quebec City's mayor from 1894 to 1906.

Edward A. Hoare was selected as Chief Engineer for the Company throughout this time,[8] while Collingwood Schreiber was the Chief Engineer of the Department of Railways and Canals in Ottawa.[9] Hoare had never worked on a cantilever bridge structure longer than 300 ft.[8][10] Schreiber was assisted until July 9, 1903 by Department bridge engineer R.C. Douglas, at which time Douglas was deposed for his opposition to the calculations that were submitted by the contractors.[11] Schreiber subsequently requested the support of another qualified bridge engineer, but was effectively overruled by the Cabinet on August 15, 1903. Thereafter, QBRC consulting engineer Theodore Cooper was completely in charge of the works,[12] and on July 1, 1905,[9] Schreiber was demoted and replaced as deputy minister and chief engineer by MJ Butler.[9][13]

By 1904, the southern half of the structure was taking shape. However, preliminary calculations made early in the planning stages were never properly checked when the design was finalized, and the actual weight of the bridge was far in excess of its carrying capacity. The dead load was too heavy. All went well until the bridge was nearing completion in the summer of 1907, when the QBRC site engineering team under Norman McLure began noticing increasing distortions of key structural members already in place.

McLure became increasingly concerned and wrote repeatedly to QBRC consulting engineer Theodore Cooper, who at first replied that the problems were minor. The Phoenix Bridge Company officials claimed that the beams must already have been bent before they were installed, but by August 27 it had become clear to McLure that this was wrong. A more experienced engineer might have telegraphed Cooper, but McLure wrote him a letter, and then went to New York to meet with him on August 29, 1907. Cooper then agreed that the issue was serious, and promptly telegraphed to the Phoenix Bridge Company: "Add no more load to bridge till after due consideration of facts." The two engineers then went to the Phoenix offices.

However, the message had not been passed on to Quebec before it was too late. Near quitting time that same afternoon, after four years of construction, the south arm and part of the central section of the bridge collapsed into the St. Lawrence River in just 15 seconds. Of the 86 workers on the bridge that day, 75 were killed and the rest were injured,[14] making it the world's worst bridge construction disaster. Of these victims, 33 (some sources say 35) were Mohawk steelworkers from the Kahnawake reserve near Montreal; they were buried at Kahnawake under crosses made of steel beams.[15]

On August 30, 1907, a Royal Commission of inquiry into the disaster was provisionally appointed by the Deputy Minister in charge of the Department of Railways and Canals (Butler), with the concurrence of the Minister. The Royal Commission, which was granted by Edward VII by advice of his Governor General, Albert Grey, on August 31, 1907, consisted of three members, who were all engineers of good standing: Mr. Henry Holgate, of Montreal, Mr. JGG Kerry, of Campbellford, Ontario also an instructor at McGill University, and Professor John Galbraith, then dean of the Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering at the University of Toronto. The Commission document conferred upon the commissioners full powers to summon witnesses and documents, and to express "any opinion they may see to express thereon". The Commissioners presented their Report in full on February 20, 1908, issued 15 conclusions, and included the hindsight work of consulting bridge engineer C.C. Schneider, of Philadelphia (a fulfillment of the 1903 request of Schreiber, supra).[16]

The Commissioners found responsibility for the failure to lie at the feet of two men, consulting engineer Theodore Cooper and Peter L. Szlapka, Chief Designing Engineer for Phoenix Bridge Company:

(c) The design of the chords that failed was made by Mr. P.L. Szlapka, the designing engineer of the Phoenix Bridge Company

(d) This design was examined and officially approved by Mr. Theodore Cooper, consulting engineer of the Quebec Bridge and Railway Company.

(e) The failure cannot be attributed directly to any cause other than errors in judgment on the part of these two engineers.

Cooper escaped penal sanction.[17] It is presumed that Szlapka escaped as well. The Commissioners also found that:

(k) The failure on the part of the Quebec Bridge and Railway Company to appoint an experienced bridge engineer to the position of chief engineer was a mistake. This resulted in a loose and inefficient supervision of all parts of the work on the part of the Quebec Bridge and Railway Company.

The abortive construction of the Quebec Bridge spanned the careers of two Ministers of Railways and Canals, and one temporary replacement, who was on the job for five months immediately preceding the disaster. A popular myth is that the iron and steel from the collapsed bridge, which could not be reused for construction, was used to forge the early Iron Rings worn by graduates of Canadian engineering schools starting in 1925.[18]

Second design and collapse of September 11, 1916

After a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the collapse, construction started on a second bridge. Three engineers were appointed: H. E. Vautelet, a former engineer for the Canadian Pacific Railways, Maurice FitzMaurice from Britain, who worked on the construction of the Forth Bridge, and Ralph Modjeski from Chicago. Vautelet was President and Chief Engineer. The new design was again for a bridge with a single long cantilever span, but a much more massive one.

On September 11, 1916, when the central span was being raised into position, it fell into the river, killing 13 workers.[14] The chief engineer was made aware of the problem six weeks before the collapse by the engineer that was responsible for the construction of the centre section, Frants Lichtenberg. Frants Lichtenberg was also working as an inspector for the federal government of Canada at the time.[19][20] Immediately, fears of German sabotage were reported; however, it was soon clear that another tragic construction accident had befallen the structure (a problem with the hoisting devices). Re-construction began almost immediately after the accident and special permission granted for the bridge builders to acquire the steel that was in high demand because of the War effort. The fallen central span still lies at the bottom of the river. After the bridge's completion in 1917, special passes were required for those wanting to cross the structure. Armed soldiers, and later Dominion Police, guarded the structure and checked passes until the end of the War.

Completion

Construction was ultimately completed in August 1919, at a total cost of $25 million and 88 bridgeworkers' lives. On December 3, 1919, the Quebec Bridge opened for rail traffic, after almost two decades of construction. Its centre span of 549 metres (1800 ft) remains the longest cantilevered bridge span in the world and is considered a major engineering feat.

Post-completion history

The bridge was built and designed primarily as a railway bridge, but the streetcar lines and one of the two railway tracks were converted into automobile and pedestrian/cycling lanes in subsequent years. In 1970 the Pierre Laporte Suspension Bridge opened just upstream to accommodate freeway traffic on Autoroute 73.

The Quebec Bridge was declared a historic monument in 1987 by the Canadian and American Society of Civil Engineers, and on January 24, 1996, the bridge was declared a National Historic Site of Canada.

The bridge was built as part of the National Transcontinental Railway, which was merged into the Canadian Government Railways and later became part of the Canadian National Railway (CN). The Canadian Government Railways company was maintained by the federal government until 1993, when a Privy Council order dated July 22 authorized the sale of Canadian Government Railways to the Crown corporation CN for one dollar (CAD). On this date, the Quebec Bridge also came under complete ownership of CN. CN was privatized in November 1995, making the bridge privately owned.

Despite its private ownership, CN receives federal and provincial funding to undertake repairs and maintenance on the structure. Its railway designation is mile 0.2 subdivision Bridge.

Aftermath

In Canada, and many other countries, the aftermath of the Quebec bridge collapse still affects many today. This disaster showed what unquestionable power an engineer could have at the time in a project that was improperly supervised. As one result, Galbraith and others formed around 1925 what are now recognized as organizations of Professional Engineers. P.Engs are under different rules and regulations based on the organization to which they belong. General guidelines include that an engineer must pass an ethical examination, be able to show good character through the use of character witnesses, and have applicable engineering experience (in Canada this constitutes a minimum of four years' practice under a certified Professional Engineer). Moreover, engineers must be registered in the province in which they work.[21] These engineering organizations are regulated by the respective provinces and the title "Professional Engineer" (or "Ingénieur" in Quebec) is reserved only to members who belong to this organization.

On August 29, 2006, a year-long commemoration was begun in the Kahnawake Reserve for the lives of the 33 Mohawk casualties.[22] One year later, on August 29, 2007, memorial services were held to dedicate a concrete structure displaying the victims' names on the Lévis side of the bridge, and to unveil a steel replica of the bridge in Kahnawake.[23]

Corrosion and maintenance controversy

In 2015, the Quebec bridge was included in a list of the 10 most endangered historic sites in Canada by the National Trust of Canada due to long overdue paint and repair work.

"It is estimated that 60% of the bridge is covered in corrosive rust. Since its transfer to CN Rail by the federal government in 1993, maintenance and restoration programs for this historic infrastructure have been cut back. In November 2014, the City of Quebec, City of Lévis, Province of Quebec, and Government of Canada joined in pledging half the estimated $200 million cost of repainting and restoring the Quebec Bridge. To date, CN Rail has not agreed to match this amount. CN Rail has deemed the proposed sanding and restorative paint work to be “aesthetic” and therefore unnecessary, a categorization supported by a ruling of the Superior Court of Quebec.

The corrosion, accelerated by exposure to extremes of weather, will ultimately result in the loss of the bridge’s mechanical properties—and potentially, its structural integrity as well." [24]

In May 2016, Jean-Yves Duclos, the Canadian federal cabinet minister in charge of the Quebec region revealed that a lease agreement between the CN and the federal government indicates that the CN shall not be required to pay more than $10 M towards the paint work until the lease expires in 2053. The Canadian government is now proposing to invest $75 M to paint the bridge and is asking the Quebec provincial government to step in and invest an estimated additional $275 M to complete the work. The mayor of Quebec City, Regis Labeaume has accused the Federal Government of breaching a promise made during the 2015 electoral campaign to act upon the maintenance of the bridge [25]

See also

- List of crossings of the Saint Lawrence River

- List of bridges in Canada

- High Steel, a 1966 documentary on Mohawk high steel workers that also documents the 1907 collapse

References

- ↑ Québec Bridge National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ↑ 50-51 Vic c.98

- ↑ 54-55 Vic c.107

- ↑ 60-61 Vic c.69

- ↑ 63-64 Vic c.115

- ↑ 3 Edw VII c.177

- ↑ 3 Edw VII c.54

- 1 2 Wm. D. Middleton: "The Bridge at Quebec" Indiana University Press, 2001

- 1 2 3 Dictionary of Canadian Biography: "SCHREIBER, Sir COLLINGWOOD"

- ↑ Notes from USask Notes on General Engineering, "Engineering in Society 449"

- ↑ Royal Commission, p.41

- ↑ Royal Commission, p.48

- ↑ Biographical Dictionary of Canadian Engineers (at UWO): "Butler, Matthew Joseph"

- 1 2 Deachman, Bruce (August 5, 2016). "The five worst bridge collapses in Canadian history". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ↑ Cecil Adams, "The Straight Dope: Why do so many Native Americans work on skyscrapers?" Chicago Reader, December 18, 1992.

- ↑ Royal Commission Quebec Bridge Inquiry Report (Report). Ottawa: SE Dawson, by order of Parliament. 1908.

- ↑ "Theodore Cooper Dies at 81" New York Times obituary.

- ↑ Information Relevant to the Iron Ring Ceremony Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., November 22, 2001; Retrieved April 4, 2010

- ↑ Frants Lichtenberg's letter to his son Steen Lichtenberg in 1954, describing the construction of the Quebec Bridge.

- ↑ Middleton, William D. (2001). The Bridge at Quebec. Indiana University Press. p. 158. ISBN 0-253-33761-5. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

- ↑ Lawson, Don (2005). Engineering Disasters - Lessons to be Learned. ASME Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-7918-0230-2.

- ↑ "Kahnawake Mohawks mark 1907 Quebec bridge disaster", August 31, 2006

- ↑ "Mohawks join memorial for 75 who died in 1907 Quebec Bridge collapse", August 29, 2007

- ↑ Seim, Charles (May 2008). "Why Bridges Have Failed Throughout History". Civil Engineering. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers. 78 (8): 64–71, 84–87. ISSN 0885-7024.

- ↑ Cook, Richard J. (1987). The Beauty of Railroad Bridges in North America—Then and Now. Golden West Books, California (USA). ISBN 0-87095-097-5.

- Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (April 1916). "Photos of Quebec Bridge". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXXI: 662–663. Retrieved 2012-01-11.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quebec Bridge. |

- (in French)Pont de Québec timeline

- The Collapse of the Quebec City Bridge

- Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer

- The Iron Ring (archive)

- Photo Centre Span Collapse

- Article on "Bridge Collapse Cases/Quebec Bridge" at MatDL

- Quebec Bridge (1907) at Structurae

- Quebec Bridge (1917) at Structurae

- 3D model