Polyvinylidene fluoride

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Poly(1,1-difluoroethylene) [1] | |

| Other names

Polyvinylidene difluoride; poly(vinylene fluoride); Kynar; Hylar; Solef; Sygef; poly(1,1-difluoroethane) | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.133.181 |

| MeSH | polyvinylidene+fluoride |

| Properties | |

| -(C2H2F2)n- | |

| Appearance | Whitish or translucent solid |

| Insoluble | |

| Structure | |

| 2.1 D[2] | |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

PVF, PVC, PTFE |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

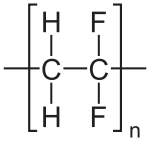

Polyvinylidene fluoride, or polyvinylidene difluoride, (PVDF) is a highly non-reactive thermoplastic fluoropolymer produced by the polymerization of vinylidene difluoride.

PVDF is a specialty plastic used in applications requiring the highest purity, as well as resistance to solvents, acids and bases. Compared to other fluoropolymers, like polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon), PVDF has a low density (1.78 g/cm3).

It is available as piping products, sheet, tubing, films, plate and an insulator for premium wire. It can be injected, molded or welded and is commonly used in the chemical, semiconductor, medical and defense industries, as well as in lithium-ion batteries. It is also available as a crosslinked closed-cell foam, used increasingly in aviation and aerospace applications.

As a fine powder grade, it is an ingredient in high-end paints for metals. These PVDF paints have extremely good gloss and color retention. They are in use on many prominent buildings around the world, such as the Petronas Towers in Malaysia and Taipei 101 in Taiwan, as well as on commercial and residential metal roofing.

PVDF membranes are used for western blots for immobilization of proteins, due to its non-specific affinity for amino acids.

Names

PVDF is sold under a variety of brand names including KF (Kureha), Hylar (Solvay), Kynar (Arkema) and Solef (Solvay).

Properties

In 1969, strong piezoelectricity was observed in PVDF, with the piezoelectric coefficient of poled (placed under a strong electric field to induce a net dipole moment) thin films as large as 6–7 pC/N: 10 times larger than that observed in any other polymer.[3]

PVDF has a glass transition temperature (Tg) of about −35 °C and is typically 50–60% crystalline. To give the material its piezoelectric properties, it is mechanically stretched to orient the molecular chains and then poled under tension. PVDF exists in several forms: alpha (TGTG'), beta (TTTT), and gamma (TTTGTTTG') phases, depending on the chain conformations as trans (T) or gauche (G) linkages. When poled, PVDF is a ferroelectric polymer, exhibiting efficient piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties. These characteristics make it useful in sensor and battery applications. Thin films of PVDF are used in some newer thermal camera sensors.

Unlike other popular piezoelectric materials, such as PZT, PVDF has a negative d33 value. Physically, this means that PVDF will compress instead of expand or vice versa when exposed to the same electric field.

Processing

PVDF may be synthesized from the gaseous VDF monomer via a free radical (or controlled radical) polymerization process. This may be followed by processes such as melt casting, or processing from a solution (e.g. solution casting, spin coating, and film casting). Langmuir-Blodgett films have also been made. In the case of solution-based processing, typical solvents used include dimethylformamide and the more volatile butanone. In aqueous emulsion polymerization, the fluorosurfactant perfluorononanoic acid is used in anion form as a processing aid by solubilizing monomers.[5] Compared to other fluoropolymers, it has an easier melt process because of its relatively low melting point of around 177 °C.

Processed materials are typically in the non-piezoelectric alpha phase. The material must either be stretched or annealed to obtain the piezoelectric beta phase. The exception to this is for PVDF thin films (thickness in the order of micrometres). Residual stresses between thin films and the substrates on which they are processed are great enough to cause the beta phase to form.

In order to obtain a piezoelectric response, the material must first be poled in a large electric field. Poling of the material typically requires an external field of above 30 MV/m. Thick films (typically >100 µm) must be heated during the poling process in order to achieve a large piezoelectric response. Thick films are usually heated to 70–100 °C during the poling process.

A quantitative defluorination process was described by mechanochemistry,[6] for safe eco-friendly PVDF waste processing.

Applications

PVDF is commonly used as insulation on electrical wires, because of its combination of flexibility, low weight, low thermal conductivity, high chemical corrosion resistance, and heat resistance. Most of the narrow 30-gauge wire used in wire wrap circuit assembly and printed circuit board rework is PVDF-insulated. In this use the wire is generally referred to as "Kynar wire", from the trade name.

The piezoelectric properties of PVDF are exploited in the manufacture of tactile sensor arrays, inexpensive strain gauges, and lightweight audio transducers. Piezoelectric panels made of PVDF are used on the Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter, a scientific instrument of the New Horizons space probe that measures dust density in the outer solar system.

PVDF is the standard binder material used in the production of composite electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. 1−2% weight solution of PVDF dissolved in N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) is mixed with an active lithium storage material such as graphite, silicon, tin, LiCoO2, LiMn2O4, or LiFePO4 and a conductive additive such as carbon black or carbon nanofibers. This slurry is cast onto a metallic current collector and the NMP is evaporated to form a composite or paste electrode. PVDF is used because it is chemically inert over the potential range used, and does not react with the electrolyte or lithium.

In the biomedical sciences, PVDF is used in immunoblotting as an artificial membrane (usually with 0.22 or 0.45 micrometre pore sizes), on which proteins are transferred using electricity (see western blotting). PVDF is resistant to solvents and, therefore, these membranes can be easily stripped and reused to look at other proteins. PVDF membranes may be used in other biomedical applications as part of a membrane filtration device, often in the form of a syringe filter or wheel filter. The various properties of this material, such as heat resistance, resistance to chemical corrosion, and low protein binding properties, make this material valuable in the biomedical sciences for preparation of medications as a sterilizing filter, and as a filter to prepare samples for analytical techniques such as HPLC, where small amounts of particulate matter can damage sensitive and expensive equipment.

PVDF is used for specialty monofilament fishing lines, sold as fluorocarbon replacements for nylon monofilament. The surface is harder, so it is more resistant to abrasion and sharp fish teeth. Its optical density is lower than nylon, which makes the line less discernible to sharp fish eyes. It is also denser than nylon, making it sink faster towards fish.[7]

PVDF transducers have the advantage of being dynamically more suitable for modal testing than semiconductor piezoresistive transducers, and more compliant for structural integration than piezoceramic transducers. For those reasons, the use of PVDF active sensors is a keystone for the development of future structural health monitoring methods, due to their low cost and compliance.[8]

Other forms

Copolymers

Copolymers of PVDF are also used in piezoelectric and electrostrictive applications. One of the most commonly used copolymers is P(VDF-trifluoroethylene), usually available in ratios of about 50:50 wt% and 65:35 wt% (equivalent to about 56:44 mol% and 70:30 mol%). Another one is P(VDF-tetrafluoroethylene). They improve the piezoelectric response by improving the crystallinity of the material.

While the copolymers' unit structures are less polar than that of pure PVDF, the copolymers typically have a much higher crystallinity. This results in a larger piezoelectric response: d33 values for P(VDF-TFE) have been recorded to be as high as −38 pC/N[9] versus −33 pC/N in pure PVDF.[10]

Terpolymers

Terpolymers of PVDF are the most promising one in terms of electromechanically induced strain. The most commonly used PVDF-based terpolymers are P(VDF-TrFE-CTFE) and P(VDF-TrFE-CFE).[11][12] This relaxor-based ferroelectric terpolymer is produced by random incorporation of the bulky third monomer (CTFE) into the polymer chain of P(VDF-TrFE) copolymer (which is ferroelectric in nature). This random incorporation of CTFE in P(VDF-TrFE) copolymer disrupts the long-range ordering of the ferroelectric polar phase, resulting in the formation of nano-polar domains. When an electric field is applied, the disordered nano-polar domains change their conformation to all-trans conformation, which leads to large electrostrictive strain and a high room-temperature dielectric constant of ~50.[13]

See also

- Ferroelectric polymers

- Klaiber's law

- Ferroelectricity

- Piezoelectricity

- Pyroelectricity

- Plastic

- Polymer

- Lithium ion battery

References

- ↑ "poly(vinylene fluoride) (CHEBI:53250)". Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ↑ Zhang, Q. M., Bharti, V., Kavarnos, G., Schwartz, M. (Ed.), (2002). "Poly (Vinylidene Fluoride) (PVDF) and its Copolymers", Encyclopedia of Smart Materials, Volumes 1–2, John Wiley & Sons, 807–825.

- ↑ Kawai, Heiji (1969). "The Piezoelectricity of Poly (vinylidene Fluoride)". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 8 (7): 975. doi:10.1143/JJAP.8.975.

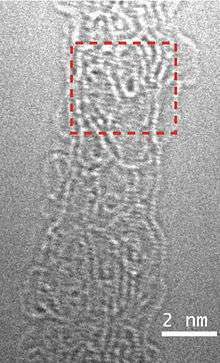

- ↑ Lolla, Dinesh; Gorse, Joseph; Kisielowski, Christian; Miao, Jiayuan; Taylor, Philip L.; Chase, George G.; Reneker, Darrell H. (2015). "Polyvinylidene fluoride molecules in nanofibers, imaged at atomic scale by aberration corrected electron microscopy". Nanoscale. doi:10.1039/C5NR01619C.

- ↑ Prevedouros K, Cousins IT, Buck RC, Korzeniowski SH (January 2006). "Sources, fate and transport of perfluorocarboxylates". Environ Sci Technol. 40 (1): 32–44. PMID 16433330. doi:10.1021/es0512475.

- ↑ Zhang, Qiwu; Lu, Jinfeng; Saito, Fumio; Baron, Michel (2001). "Mechanochemical solid-phase reaction between polyvinylidene fluoride and sodium hydroxide". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 81 (9): 2249. doi:10.1002/app.1663.

- ↑ Seaguar history — Kureha America, Inc. manufacturer's site

- ↑ Guzman, E.; Cugnoni, J; Gmür, T (2013). "Survivability of integrated PVDF film sensors to accelerated ageing conditions in aeronautical/aerospace structures". Smart Mater Struct. 22 (6): 065020. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/22/6/065020.

- ↑ Omote, Kenji; Ohigashi, Hiroji; Koga, Keiko (1997). "Temperature dependence of elastic, dielectric, and piezoelectric properties of "single crystalline films of vinylidene fluoride trifluoroethylene copolymer". Journal of Applied Physics. 81 (6): 2760. doi:10.1063/1.364300.

- ↑ Nix, E. L.; Ward, I. M. (1986). "The measurement of the shear piezoelectric coefficients of polyvinylidene fluoride". Ferroelectrics. 67: 137. doi:10.1080/00150198608245016.

- ↑ Xu, Haisheng; Cheng, Z.-Y.; Olson, Dana; Mai, T.; Zhang, Q. M.; Kavarnos, G. (16 April 2001). "Ferroelectric and electromechanical properties of poly(vinylidene-fluoride–trifluoroethylene–chlorotrifluoroethylene) terpolymer". Applied Physics Letters. AIP Publishing LLC, American Institute of Physics. 78 (16): 2360–2362. doi:10.1063/1.1358847.

- ↑ Bao, Hui-Min; Song, Jiao-Fan; Zhang, Juan; Shen, Qun-Dong; Yang, Chang-Zheng; Zhang, Q. M. (3 April 2007). "Phase Transitions and Ferroelectric Relaxor Behavior in P(VDF−TrFE−CFE) Terpolymers". Macromolecules. ACS Publications. 40 (7): 2371–2379. doi:10.1021/ma062800l.

- ↑ Ahmed, Saad; Arrojado, Erika; Sigamani, Nirmal; Ounaies, Zoubeida (14 May 2015). Goulbourne, Nakhiah C., ed. "Electric field responsive origami structures using electrostriction-based active materials". Proceedings of SPIE: Behavior and Mechanics of Multifunctional Materials and Composites 2015. Society of Photographic Instrumentation Engineers (SPIE). 9432. ISBN 9781628415353. doi:10.1117/12.2084785.