Political history of medieval Karnataka

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Karnataka |

|---|

|

| Categories |

|

The political history of medieval Karnataka spans the 4th to the 16th centuries, when the empires that evolved in the Karnataka region of India made a lasting impact on the subcontinent. Before this, alien empires held sway over the region, and the nucleus of power was outside modern Karnataka. The medieval era can be broadly divided into several periods: The earliest native kingdoms and imperialism; the successful domination of the Gangetic plains in northern India and rivalry with the empires of Tamilakam over the Vengi region; and the domination of the southern Deccan and consolidation against Muslim invasion. The origins of the rise of the Karnataka region as an independent power date back to the fourth-century birth of the Kadamba Dynasty of Banavasi, the earliest of the native rulers to conduct administration in the native language of Kannada in addition to the official Sanskrit. This is the historical starting point in studying the development of the region as an enduring geopolitical entity and of Kannada as an important regional language.

In the southern regions of Karnataka, the Western Gangas of Talakad were contemporaries of the Kadambas. The Kadambas and Gangas were followed by the imperial dynasties of the Badami Chalukya Empire, the Rashtrakuta Empire, the Western Chalukya Empire, the Hoysala Empire and the Vijayanagara Empire, all patronising the ancient Indic religions while showing tolerance to the new cultures arriving from the west of the subcontinent. The Muslim invasion of the Deccan resulted in the breaking away of the feudatory Sultanates in the 14th century. The rule of the Bahamani Sultanate of Bidar and the Bijapur Sultanate from the northern Deccan region caused a mingling of the ancient Hindu traditions with the nascent Islamic culture in the region. The hereditary ruling families and clans ably served the large empires and upheld the local culture and traditions. The fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565 brought about a slow disintegration of Kannada-speaking regions into minor kingdoms that struggled to maintain autonomy in an age dominated by foreigners until unification and independence in 1947.

Kadambas and Gangas

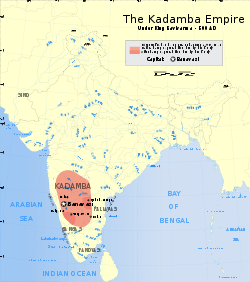

Prior to and during the early centuries of the first millennium, large areas of the Karnataka region was ruled by such imperial powers as the Mauryas of Maghada and later the Satavahanas, empires whose centres of power were in the Gangetic plains and Central India respectively. With the weakening of the Satavahanas, the Pallavas of Kanchi took control for a brief duration.[1] In the 4th century, the rise to power of the Kadamba Dynasty of Banavasi identified the Karnataka region as an independent political entity and Kannada as an administrative language from the middle of the 5th century.[2] The Kadambas were natives of the Talagunda region (in modern Shivamogga district) as proven by inscriptions.[3][4][5][6][7] Mayurasharma, a Brahmin native of Talagunda who was humiliated by a Pallava guard, rose in rage against the Pallava control of the Banavasi region and declared his independence in 345.[8][9][10] After many wars, the Pallava king had to accept the sovereignty of the Kadambas and Mayurasharma, the founding king, crowned himself at Banavasi (in the present day Uttara Kannada district).[11]

The fact that the Kadambas cultivated marital ties with the imperial Vakatakas and Gupta dynasties attests to their power.[12] Kakusthavarma, the most powerful ruler of the dynasty whom inscriptions describe as "ornament of the Kadamba family" and "Sun among the kings of wide spread flame", gave one daughter in marriage to Vakataka Narendrasena and another to Skandagupta, grandson of Chandragupta II of the Gupta dynasty.[13][14] Historians trace their rise to political power through the examination of the contemporaneous Sanskrit writing, Aichitya Vichara Charcha by Kshemendra, which quotes portions of a writing Kunthalesvara Dautya by the famous poet Kalidasa. Here Kalidasa describes his visit to the Kadamba kingdom as an ambassador where he was not offered a seat in the court of the Kadamba king and had to sit on the ground. Historians view this act as one of assertion by the Kadambas who considered themselves equal to the imperial Gupta dynasty.[15]

Family feuds and conflicts ended the Kadamba rule in the middle of the 6th century when the last Kadamba ruler Krishna Varma II was subdued by Pulakeshin I of the Chalukya feudatory, ending their sovereign rule. The Kadambas would continue to rule parts of Karnataka and Goa for many centuries to come but never again as an independent kingdom.[16] Some historians view the Kadambas as the originators of the Karnataka architectural tradition although there were elements in common with the structures built by the contemporaneous Pallavas of Kanchi.[17] The oldest surviving Kadamba structure is one dating to the late 5th century in Halsi in modern Belgaum district. The most prominent feature of their architectural style, one that remained popular centuries later and was used by the Hoysalas and the Vijayanagar kings, is the Kadamba Shikara (Kadamba tower) with a Kalasa (pot) on top.[18]

The Western Ganga Dynasty, contemporaries of the Kadambas, came to power from Kolar but in the late 4th century - early 5th century moved their capital to Talakad in modern Mysore district.[19] They ruled the region historically known as Gangavadi comprising most of the modern southern districts of Karnataka. Acting as a buffer state between the Kannada kingdoms of Karnataka region and the Tamil kingdoms of Tamilakam, the Western Ganga architectural innovations show mixed influences.[20] Their sovereign rule ended around the same time as the Kadambas when they came under the Badami Chalukya control. The Western Gangas continued to rule as a feudatory till the beginning of the eleventh century when they were defeated by the Cholas of Tanjavur.[21] Important figures among the Gangas were King Durvinita and Shivamara II, admired as able warriors and scholars,[22] and minister Chavundaraya who was a builder, a warrior and a writer in Kannada and Sanskrit.[23][24] The most important architectural contributions of these Gangas are the monuments and basadis of Shravanabelagola, the monolith of Gomateshwara termed as the mightiest achievement in the field of sculpture in ancient Karnataka and the Panchakuta basadi ( five towers) at Kambadahalli.[25] Their free standing pillars (called Mahasthambhas and Brahmasthambhas) and Hero stones (virgal) with sculptural detail are also considered a unique contribution.[26]

Badami Chalukyas

The Chalukya dynasty, natives of the Aihole and Badami region in Karnataka, were at first a feudatory of the Kadambas.[27][28] [29][30][31] They encouraged the use of Kannada in addition to the Sanskrit language in their administration.[32][33] In the middle of the 6th century the Chalukyas came into their own when Pulakeshin I made the hill fortress in Badami his center of power.[34] During the rule of Pulakeshin II a south Indian empire sent expeditions to the north past the Tapti River and Narmada River for the first time and successfully defied Harshavardhana, the King of Northern India (Uttarapatheswara). The Aihole inscription of Pulakeshin II, written in classical Sanskrit language and old Kannada script dated 634,[35][36] proclaims his victories against the Kingdoms of Kadambas, Western Gangas, Alupas of South Canara, Mauryas of Puri, Kingdom of Kosala, Malwa, Lata and Gurjaras of southern Rajasthan. The inscription describes how King Harsha of Kannauj lost his Harsha (joyful disposition) on seeing a large number of his war elephants die in battle against Pulakeshin II.[37][38][39][40][41]

These victories earned him the title Dakshinapatha Prithviswamy (lord of the south). Pulakeshin II continued his conquests in the east where he conquered all kingdoms in his way and reached the Bay of Bengal in present-day Orissa. A Chalukya viceroyalty was set up in Gujarat and Vengi (coastal Andhra) and princes from the Badami family were dispatched to rule them. Having subdued the Pallavas of Kanchipuram, he accepted tributes from the Pandyas of Madurai, Chola dynasty and Cheras of the Kerala region. Pulakeshin II thus became the master of India, south of the Narmada River.[42] Pulakeshin II is widely regarded as one of the great kings in Indian history.[43][44] Hiuen-Tsiang, a Chinese traveller visited the court of Pulakeshin II at this time and Persian emperor Khosrau II exchanged ambassadors.[45] However, the continuous wars with Pallavas took a turn for the worse in 642 when the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I avenged his father's defeat,[46] conquered and plundered the capital of Pulakeshin II who may have died in battle.[46][47] A century later, Chalukya Vikramaditya II marched victoriously into Kanchipuram, the Pallava capital and occupied it on three occasions, the third time under the leadership of his son and crown prince Kirtivarman II. He thus avenged the earlier humiliation of the Chalukyas by the Pallavas and engraved a Kannada inscription on the victory pillar at the Kailasanatha Temple.[48][49][50][51] He later overran the other traditional kingdoms of Tamil country, the Pandyas, Cholas and Keralas in addition to subduing a Kalabhra ruler.[52]

The Kappe Arabhatta record from this period (700) in tripadi (three line) metre is considered the earliest available record in Kannada poetics. The most enduring legacy of the Chalukya dynasty is the architecture and art that they left behind.[53] More than one hundred and fifty monuments attributed to them, built between 450 and 700, have survived in the Malaprabha basin in Karnataka.[54] The constructions are centred in a relatively small area within the Chalukyan heartland. The structural temples at Pattadakal, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the cave temples of Badami, the temples at Mahakuta and early experiments in temple building at Aihole are their most celebrated monuments.[53] Two of the famous paintings at Ajanta cave no. 1, "The Temptation of the Buddha" and "The Persian Embassy" are also credited to them. [55] [56] Further, they influenced the architecture in far off places like Gujarat and Vengi as evidenced in the Nava Brahma temples at Alampur.[57]

Rashtrakutas

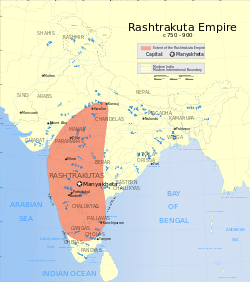

In the middle of the 8th century the Chalukya rule was ended by their feudatory, the Rashtrakuta family rulers of Berar (in present-day Amravati district of Maharashtra). Sensing an opportunity during a weak period in the Chalukya rule, Dantidurga trounced the great Chalukyan "Karnatabala" (power of Karnata).[58][59] Having overthrown the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas made Manyakheta their capital (modern Malkhed in Gulbarga district).[60][61] Although the origins of the early Rashtrakuta ruling families in central India and the Deccan in the 6th and 7th centuries is controversial, during the eighth through the tenth centuries they emphasised the importance of the Kannada language in conjunction with Sanskrit in their administration. Rashtrakuta inscriptions are in Kannada and Sanskrit only. They encouraged literature in both languages and thus literature flowered under their rule.[62][63][64][65][66]

The Rashtrakutas quickly became the most powerful Deccan empire, making their initial successful forays into the doab region of Ganges River and Jamuna River during the rule of Dhruva Dharavarsha.[67] The rule of his son Govinda III signaled a new era with Rashtrakuta victories against the Pala Dynasty of Bengal and Gurjara Pratihara of north western India resulting in the capture of Kannauj. The Rashtrakutas held Kannauj intermittently during a period of a tripartite struggle for the resources of the rich Gangetic plains.[68] Because of Govinda III's victories, historians have compared him to Alexander the Great and Pandava Arjuna of the Hindu epic Mahabharata.[69] The Sanjan inscription states the horses of Govinda III drank the icy water of the Himalayan stream and his war elephants tasted the sacred waters of the Ganges River.[70] Amoghavarsha I, eulogised by contemporary Arab traveller Sulaiman as one among the four great emperors of the world, succeeded Govinda III to the throne and ruled during an important cultural period that produced landmark writings in Kannada and Sanskrit.[71][72][73] The benevolent development of Jain religion was a hallmark of his rule. Because of his religious temperament, his interest in the arts and literature and his peace-loving nature,[71] he has been compared to emperor Ashoka.[74] The rule of Indra III in the tenth century enhanced the Rashtrakuta position as an imperial power as they conquered and held Kannauj again.[75] Krishna III followed Indra III to the throne in 939. A patron of Kannada literature and a powerful warrior, his reign marked the submission of the Paramara of Ujjain in the north and Cholas in the south.[76]

An Arabic writing Silsilatuttavarikh (851) called the Rashtrakutas one among the four principle empires of the world.[77] Kitab-ul-Masalik-ul-Mumalik (912) called them the "greatest kings of India" and there were many other contemporaneous books written in their praise.[78] The Rashtrakuta empire at its peak spread from Cape Comorin in the south to Kannauj in the north and from Banaras in the east to Broach (Bharuch) in the west.[79] While the Rashtrakutas built many fine monuments in the Deccan, the most extensive and sumptuous of their work is the monolithic Kailasanatha temple at Ellora, the temple being a splendid achievement.[80] In Karnataka their most famous temples are the Kashivishvanatha temple and the Jain Narayana temple at Pattadakal. All of the monuments are designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[81]

Western Chalukyas

In the late 10th century, the Western Chalukyas, also known as the Kalyani Chalukyas or 'Later' Chalukyas rose to power by overthrowing the Rashtrakutas under whom they had been serving as feudatories. Manyakheta was their capital early on before they moved it to Kalyani (modern Basavakalyan). Whether the kings of this empire belonged to the same family line as their namesakes, the Badami Chalukyas is still debated.[82][83] Whatever the Western Chalukya origins, Kannada remained their language of administration and the Kannada and Sanskrit literature of their time was prolific.[65][84][85][86] Tailapa II, a feudatory ruler from Tardavadi (modern Bijapur district), re-established the Chalukya rule by defeating the Rashtrakutas during the reign of Karka II. He timed his rebellion to coincide with the confusion caused by the invading Paramara of Central India to the Rashtrakutas capital in 973.[87][88][89] This era produced prolonged warfare with the Chola dynasty of Tamilakam for control of the resources of the Godavari River-Krishna River doab region in Vengi. Someshvara I, a brave Chalukyan king, successfully curtailed the growth of the Chola Empire to the south of the Tungabhadra River region despite suffering some defeats[90][91] while maintaining control over his feudatories in the Konkan, Gujarat, Malwa and Kalinga regions.[92] For approximately 100 years, beginning in the early 11th century, the Cholas occupied large areas of South Karnataka region (Gangavadi).[93]

In 1076, the ascent of the most famous king of this Chalukya family, Vikramaditya VI, changed the balance of power in favour of the Chalukyas.[94] His fifty-year reign was an important period in Karnataka's history and is referred to as the "Chalukya Vikrama era".[95] His victories over the Cholas in the late 11th and early 12th centuries put an end to the Chola influence in the Vengi region permanently.[94] Some of the well-known contemporaneous feudatory families of the Deccan under Chalukya control were the Hoysalas, the Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, the Kakatiya dynasty and the Southern Kalachuri.[94] At their peak, the Western Chalukyas ruled a vast empire stretching from the Narmada River in the north to the Kaveri River in the south. Vikramaditya VI is considered one of the most influential kings of Indian history.[96][97] Important architectural works were created by these Chalukyas, especially in the Tungabhadra river valley, that served as a conceptual link between the building idioms of the early Badami Chalukyas and the later Hoysalas.[98][99] With the weakening of the Chalukyas in the decades following the death of Vikramaditya VI in 1126, the feudatories of the Chalukyas gained their independence.

The Kalachuris of Karnataka, whose ancestors were immigrants into the southern deccan from central India, had ruled as a feudatory from Mangalavada (modern Mangalavedhe in Maharashtra).[100] Bijjala II, the most powerful ruler of this dynasty, was a commander (mahamandaleswar) during the reign of Chalukya Vikramaditya VI.[101] Seizing an opportune moment in the waning power of the Chalukyas, Bijjala II declared independence in 1157 and annexed their capital Kalyani.[102] His rule was cut short by his assassination in 1167 and the ensuing civil war caused by his sons fighting over the throne ended the dynasty as the last Chalukya scion regained control of Kalyani. This victory however, was short-lived as the Chalukyas were eventually driven out by the Seuna Yadavas.[103]

Hoysalas

The Hoysalas had become a powerful force even during their rule from Belur in the 11th century as a feudatory of the Chalukyas (in the south Karnataka region).[104] In the early 12th century they successfully fought the Cholas in the south, convincingly defeating them in the battle of Talakad and moved their capital to nearby Halebidu.[105][106] Historians refer to the founders of the dynasty as natives of Malnad Karnataka, based on the numerous inscriptions calling them Maleparolganda or "Lord of the Male (hills) chiefs" (Malepas).[104][107][108][109][110][111] With the waning of the Western Chalukya power, the Hoysalas declared their independence in the late twelfth century.

During this period of Hoysala control, distinctive Kannada literary metres such as Ragale (blank verse), Sangatya (meant to be sung to the accompaniment of a musical instrument), Shatpadi (seven line) etc. became widely accepted.[65][112][113][114] The Hoysalas expanded the Vesara architecture stemming from the Chalukyas,[115] culminating in the Hoysala architectural articulation and style as exemplified in the construction of the Chennakeshava Temple at Belur and the Hoysaleshwara Temple at Halebidu.[116] Both these temples were built in commemoration of the victories of the Hoysala Vishnuvardhana against the Cholas in 1116.[117][118] Veera Ballala II, the most effective of the Hoysala rulers, defeated the aggressive Pandya when they invaded the Chola kingdom and assumed the titles "Establisher of the Chola Kingdom" (Cholarajyapratishtacharya), "Emperor of the south" (Dakshina Chakravarthi) and "Hoysala emperor" (Hoysala Chakravarthi).[119] The Hoysalas extended their foothold in areas known today as Tamil Nadu around 1225, making the city of Kannanur Kuppam near Srirangam a provincial capital.[105] This gave them control over South Indian politics that began a period of Hoysala hegemony in the southern Deccan.[120][121]

In the early 13th century, with the Hoysala power remaining unchallenged, the first of the Muslim incursions into South India began. After over two decades of waging war against a foreign power, the Hoysala ruler at the time, Veera Ballala III, died in the battle of Madurai in 1343.[122] This resulted in the merger of the sovereign territories of the Hoysala empire with the areas administered by Harihara I, founder of the Vijayanagara Empire, located in the Tungabhadra region in present-day Karnataka. The new kingdom thrived for another two centuries with Vijayanagara as its capital.[123]

Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire quickly rose to imperial status as early as the late 14th century. During the reign of Bukka Raya I, the island of Lanka paid tributes and ambassadors were exchanged with the Ming Dynasty of China.[124][125][126] The empire's most famous rulers were Deva Raya II and the Tuluva king Krishnadevaraya. Deva Raya II (known as Gajabetekara or hunter of elephants) ascended the throne in 1424 and was the most effective of the Sangama dynasty rulers.[127][128] He quelled rebelling feudal lords, the Zamorin of Calicut and the Quilon in the south, and invaded the island of Lanka while becoming overlord of the kings of Burma at Pegu and Tanasserim.[129][130] After a brief decline, the empire reached its peak in the early 16th century during the rule of Krishnadevaraya when the Vijayanagara armies were consistently victorious. The empire annexed areas formerly under the Sultanates in the northern Deccan and the territories in the eastern Deccan, including Kalinga, while simultaneously maintaining control over all its subordinates in the south.[131]

Many important monuments at Hampi were either completed or commissioned during the reign of Krishnadevaraya. The enduring legacy of this empire is the vast open-air theatre of monuments at the regal capital, Vijayanagara, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. Vijayanagara architecture is a vibrant blend of the preceding Chalukya, Hoysala, Pandya and Chola styles.[132] Literature in Telugu, Kannada, Tamil and Sanskrit languages found royal patronage. Telugu attained its height in popularity and reached its peak under Krishnadevaraya.[133] The Kannada Haridasa movement contributed greatly to Carnatic music and fostered a strong Hindu sentiment across South India.[134][135][136] With the defeat of the Vijayanagara Empire in the Battle of Talikota in 1565 by the Deccan sultanates, the Karnataka region and South India in general became fragmented and subsumed under the rule of various former feudatories of the empire. A diminished Vijayanagara Empire moved its capital to Penukonda in modern Andhra Pradesh and later to Chandragiri and Vellore before disintegrating. In the south and coastal Karnataka region, the Kingdom of Mysore and the Keladi Nayaka of Shimoga held sway while the northern regions were under the control of the Bijapur Sultanate.[137] The Nayaka kingdom lasted into the 18th century before merging with the Kingdom of Mysore which remained a princely state until Indian independence in 1947, though they came under the British Raj (rule) in 1799 following the defeat and death of the last independent Mysore king, Tipu Sultan.

Bahmani Sultanate

The Bahmani Sultanate, a contemporary of the Vijayanagara Empire, was founded in 1347 by Alla-ud-din-Hasan, a breakaway commander of the armies of the northern invaders led by Mohammed-bin-Tughlaq. The capital was Gulbarga but was later moved further north to Bidar in 1430.[138] The first of the Muslim invasions of the Deccan came in the early decades of the 14th century. At its peak, the Bahamani kingdom extended from the Krishna River in the south to Penganga River in the north, thus covering the regions of northern parts of modern Karnataka, parts of Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. The most famous of the Bahamani Kings was Firuz Shah (also known as Taj Ud Din Firuz), who ruled from 1397 to 1422.[139] Militarily, the rule of Firuz Shah had uneven success against the Vijayanagara kings while he was more convincingly successful against the Kherla rulers of Madhya Pradesh and the Vema Reddies of Rajamundry, areas that he annexed in 1417. His last encounter with the Vijayanagara armies in 1417 was disastrous and led to his defeat, ill health and ultimate death in 1422.[139]

Contemporary writers such as Tabataba, in his writings have heaped praise on Firuz Shah. Tabataba wrote of the king as, "[a]n impetuous, mighty monarch who patronised learned men, Sheiks and hermits", while Shirazi described him as "a just, pious and generous king and one without equal". He has earned the honorific Sultan-i-ghazian for his bravery, tolerant nature and patronage of the fine arts.[140] In the opinion of one historian, Firuz Shah was one of the most notable Sultans to rule in India.[141] Another well-known figure from this kingdom was Kwaja Mahamud Gavan, the prime minister, who served under several kings and regents. He rose above the kings and princess of the dynasty by virtue of his ministerial, administrative, martial, literary and philanthropic abilities. A Persian by descent and a visitor to Bidar in 1445, he impressed the ruling Sultan Alla-ud-din II and was chosen to become a minister in his court. As a commander he was able to extend the kingdom from Hubli in the south to Goa in the west and Kondavidu and Rajamahendri in the east. He soon rose to the position of prime minister (Vakil-Us-Sultanat).[142]

The Bahamanis introduced the large-scale use of paper in administration and began the Indo-Sarasenic architectural style, designed and constructed by Persian architects and artisans, (also known as Deccani architecture) with its local influences in Karnataka.[143] The Sultanate monuments of Bidar and Gulbarga are testimony to their interest in architecture. The Bande Nawaz tombs and a Jama Masjid in Gulbarga which exhibits a Spanish influence are well known. In Bidar, their buildings have Persian, Turkish, Arabic and Roman influences (the Solah Khamba mosque being an example).[144] Rangin Mahal, Gangan Mahal, Tarkash Mahal, Chini Mahal, Nagina Mahal and the Taqk Mahal are some of the palaces built by them that have retained their beauty. The Ahmad Shah Wali tombs are noted for their decor, and the school of learning (madrasa) built by Gavan in Bidar (1472), with its lecture halls, library, mosque and residential houses are also famous.[145] In the later part of the 15th century, with a growing rift between the local Deccani Muslims and the Pardeshi Muslims (foreign) who occupied influential positions in the kingdom, the execution of Gavan under dubious circumstances in 1481, and constant wars with the Vijayanagara kings weakened the Bahamani Kingdom eventually bringing about its end in 1527.[146]

Bijapur Sultanate

The Bijapur Sultanate (or Adilshahi Kingdom) emerged towards the end of the 15th century with the weakening of the Bahmani Sultanate . The main sources of information about this kingdom comes from contemporaneous inscriptions and writings in Persian and Kannada, travelogues of European visitors to the Deccan and inscriptions of neighbouring kingdoms.[147] In 1489, Yusuf Adilkhan, a Turkic general in the Bahmani army, broke away to found the kingdom from modern Bijapur . Throughout his rule, the Sultanate was at war with the Vijayanagara Empire over the strategic Raichur doab, with the Portuguese over Goa, with the Barid Shahis of Bidar and later with the erstwhile feudatories of the Vijayanagara Empire who had gained independence after 1565. The Italian writer Varathema wrote about the founder Adilkhan and Bijapur, "A powerful and prosperous king", "the city was encircled by many fortifications and contained beautiful and majestic buildings".[147]

Inter-Sultanate marriages normalised relations and Ali I (1557–1580) joined a confederacy of Sultanates who eventually inflicted a crushing defeat on the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565.[148] The most notable ruler of the dynasty was Ibrahim II (1580–1626) who ascended the throne as a nine-year-old with Chandbibi, the king's aunt acting as the regent. Later when Ibrahim II was defeated by the first of the Moghul incursions into the Deccan, he gave his daughter in marriage to Daniyal, a son of Emperor Akbar, but managed to collect tributes from the former feudatories of the Vijayanagara Empire.[149] According to a historian, the rule of Ibrahim II was the high point of the Bijapur Sultanate.[150] A tolerant king inclined to the fine arts, the earliest book on music in Urdu language called Kitab-e-Nauras is ascribed to him. The opening song in the book is an invocation of the Hindu Goddess Saraswati.[149] During the rule of his son Muhammad, Shahji Bhosle from Ahmadnagar joined the Bijapur army and along with commander Ranadullah Khan conducted many successful campaigns in the southern Deccan collecting tribute from local rulers there. The final end of the diminished Vijayanagara Empire ruling from Vellore came during these campaigns.[151]

However, the rise of Maratha Shivaji and constant invasions by the Mughals from the north took its toll on the kingdom, eventually bringing it to an end in the later part of the 17th century. The contributions of the Bijapur Sultanate in the Indo-Saracenic idiom to the architectural landscape of Karnataka is noteworthy. Their most famous monuments are the mausoleums called Ibrahim Rauza and the Gol Gumbaz apart from many other palaces and mosques.[152] The elegance, finish and beauty of Mehtar Mahal is claimed by a historian to be equal to anything in Cairo.[153] Their Kali Masjid at Lakshmeshwar is a synthesis of Hindu and Muslim styles. The Ibrahim Rauza built by Ibrahim II is a combination of a mausoleum and a mosque and is called the "Taj Mahal of the Deccan".[154] The Gol Gumbaz built by Muhammad is the largest dome in India and the second largest pre-modern dome in the world after the Byzantine Hagia Sophia with an impressive "whispering gallery". Some historians consider this one of the architectural marvels of the world.[155] Persian language was given state patronage while the use of the local languages, Kannada and Marathi was popularised in local affairs.[156]

Modern era

The fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in 1565 at the Battle of Talikota started a slow disintegration of the Kannada speaking region into many short-lived palegar chiefdoms, and the better known Kingdom of Mysore and the kingdom of Keladi Nayakas, which were to later become important centres of Kannada literary production.[157] These kingdoms and the Nayakas ("chiefs") of Tamil country continued to owe nominal support to a diminished Vijayanagara Empire ruling from Penukonda (1570) and later from Chandragiri (1586) in modern Andhra Pradesh, followed by a brief period of independence.[158] By the mid-17th century, large areas in north Karnataka came under the control of the Bijapur Sultanate who waged several wars in a bid to establish a hegemony over the southern Deccan.[159] The defeat of the Bijapur Sultanate at the hands of the Mughals in late 17th century added a new dimension to the prevailing confusion.[160] The constant wars of the local kingdoms with the two new rivals, the Mughals and the Marathas, and among themselves, caused further instability in the region.[161] Major areas of Karnataka came under the rule of the Mughals and the Marathas. Under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan, the Mysore Kingdom reached its zenith of power but had to face the growing English might who by now had a firm foothold in the subcontinent.[162] After the death of Tipu Sultan in 1799 in the fourth Anglo-Mysore war, the Mysore Kingdom came under the British umbrella.[163] More than a century later, with the dawn of India as an independent nation in 1947, the unification of Kannada speaking regions as modern Karnataka state brought four centuries of political uncertainty (and centuries of foreign rule) to an end.

Timeline

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ramesh (1984), pp1–3

- ↑ From the Halmidi inscription (Ramesh 1984, pp10–11)

- ↑ The Kadambas were Kanarese speaking dravidians inducted into the Brahmin fold (Moraes 1931, p11)

- ↑ Their local tribal origins is attested by the Talagunda inscription, R.N. Nandi in Adiga (2006), p93

- ↑ Ramesh (1984), p3

- ↑ Some inscriptions claim the Kadambas came from a Naga descent (snake worshippers) making them natives of Karnataka region, Moraes (1931), p10

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p30

- ↑ From the Talagunda inscription (B.L. Rice in Kamath 2001, pp 30–31)

- ↑ Ramesh (1984), 1984, p6

- ↑ Moraes (1931), p10

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p161, part1; Kamath (2001), p30

- ↑ Moraes (1931), p26

- ↑ From the Talagunda inscription (Moraes 1931, pp26–27)

- ↑ From the Balaghat inscription of Vakataka Prithvisena (Kamath 2001, p33)

- ↑ Moraes, Desai and Panchamukhi in Kamath (2001), p33

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p162, part1; Kamath (2001), p35

- ↑ Moraes in Kamath (2001), p37

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p38

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p159, part1; Kamath (2001), p40

- ↑ The impact of the Pallava, early Chalukya and a distinct Jain influence added to their own innovations are the main features of their architectural idiom (Reddy, Sharma and Rao in Kamath 2001, p50)

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p160, part1

- ↑ Narasimhacharya (1988), p2

- ↑ Narasimhacharya (1988), p18

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp159–160, part1; Kamath (2001), p50

- ↑ Kamath (2001), pp51–52

- ↑ Fergusson in Kamath (2001), p52

- ↑ N. Laxminarayana Rao and S. C. Nandinath in Kamath 2001, p57

- ↑ Keay (2000), p168

- ↑ Jayasimha and Ranaraga, ancestors of Pulakeshin I, were administrative officers in the Badami province under the Kadambas (Fleet in Kanarese Dynasties, p343), (Moraes 1931, p51)

- ↑ Thapar (2003), p328

- ↑ Quote:"They belonged to the Karnataka country and their mother tongue was Kannada" (Sen 1999, p360); Kamath (2001), p58,

- ↑ Considerable number of their records are in Kannada (Kamath 2001, p67)

- ↑ 7th century Chalukya inscriptions call Kannada the natural language (Thapar 2003, p345)

- ↑ Sen (1999), p360

- ↑ In this composition, the poet deems himself an equal to Sanskrit scholars of lore like Bharavi and Kalidasa (Sastri 1955, p312

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p59

- ↑ Keay (2000), p169

- ↑ Sen (1999), pp361–362

- ↑ Kamath (2001), pp59–60

- ↑ Some of these kingdoms may have submitted out of fear of Harshavardhana of Kannauj (Majumdar in Kamat 2001, p59)

- ↑ The rulers of Kosala were the Panduvamshis of South Kosala (Sircar in Kamath 2001, pp59)

- ↑ Keay (2000), p170

- ↑ Kamath (2001), pp58

- ↑ Ramesh 1984, p76

- ↑ From the notes of Arab traveller Tabari (Kamath 2001, p60)

- 1 2 Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904). The Early History of India. The Clarendon press. pp. 325–327.

- ↑ Sen (1999), p362

- ↑ Thapar (2003), p331, p345

- ↑ Sastri (1955) p140

- ↑ Ramesh (1984), pp159–160

- ↑ Sen (1999), p364

- ↑ Ramesh (1984), p159

- 1 2 Hardy (1995), p65–66

- ↑ Over 125 temples exist in Aihole alone, Michael D. Gunther, 2002. "Monuments of India". Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ Arthikaje, Mangalore. "History of Karnataka—Chalukyas of Badami". © 1998–2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. Archived from the original on 2006-11-04. Retrieved 2006-11-10.

- ↑ The Badami Chalukya introduced in the western Deccan a glorious chapter alike in heroism in battle and cultural magnificence in peace (K.V. Sounderrajan in Kamath 2001, p68

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p68

- ↑ From the Rashtrakuta inscriptions (Kamath 2001, p57, p64)

- ↑ The Samangadh copper plate grant (753) confirms that feudatory Dantidurga defeated the Chalukyas and humbled their great Karnatik army (referring to the army of the Badami Chalukyas) (Reu 1933, p54)

- ↑ A capital which could put to shame even the capital of gods-From Karda plates (Altekar 1934, p47)

- ↑ A capital city built to excel that of Indra (Sastri, 1955, p4, p132, p146)

- ↑ Altekar (1934), pp411–413

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p87, part1; Literature in Kannada and Sanskrit flowered during the Rashtrakuta rule (Kamath 2001, p73, pp 88–89)

- ↑ Even royalty of the empire took part in poetic and literary activities (Thapar 2003, p334)

- 1 2 3 Narasimhacharya (1988), p68, p17–21

- ↑ Reu (1933), pp37–38

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p89, part1; His victories were a "digvijaya" gaining only fame and booty in that region (Altekar in Kamath 2001, p75)

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p90, part1

- ↑ Keay (2000), p199)

- ↑ Kamath 2001, p76

- 1 2 Chopra (2003), p91, part1

- ↑ Kavirajamarga in Kannada and Prashnottara Ratnamalika in Sanskrit (Reu 1933, p38)

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p90

- ↑ Panchamukhi in Kamath (2001), p80

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p92, part1; Altekar in Kamath 2001, p81

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p92–93, part1

- ↑ Reu (1933), p39

- ↑ Murujul Zahab by Al Masudi (944), Kitabul Akalim by Al Istakhri (951), Ashkal-ul-Bilad by Ibn Haukal (976) (Reu 1933, p41–42)

- ↑ From the Sanjan inscriptions, Dr. Jyotsna Kamat. "The Rashrakutas". 1996–2006 Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 2006-12-20.

- ↑ Keay (2000), p200

- ↑ Vijapur, Raju S. "Reclaiming past glory". Deccan Herald. Spectrum. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p137, part1

- ↑ Fleet, Bhandarkar and Altekar and Gopal B.R in (Kamath 2001, p100)

- ↑ Sen (1999), p. 393

- ↑ Sastri (1955), pp356–358; Kamath (2001), p114

- ↑ More inscriptions in Kannada are attributed to the Chalukya King Vikramaditya VI than to any other king prior to the 12th century, Kamat, Jyotsna. "Chalukyas of Kalyana". 1996–2006 Kamat's Potpourri. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ↑ From the 957 and 965 records (Kamath 2001, p101)

- ↑ Sastri 1955, p162

- ↑ Tailapa II was helped in this campaign by the Kadambas of Hanagal (Moraes 1931, pp 93–94)

- ↑ Ganguli in Kamath 2001, p103

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p167–168

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p104

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p164, p174; The Cholas occupied Gangavadi from 1004 to 1114 (Kamath 2001, p118)

- 1 2 3 Chopra (2003), p139, part1

- ↑ Thapar, 2003, pp 468–469

- ↑ Poet Bilhana in his Sanskrit work wrote "Rama Rajya" regarding his rule, poet Vijnaneshwara called him "A king like none other" (Kamath 2001, p106)

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p6

- ↑ Sastri (1955), pp 427–428; Quote:"Their creations have the pride of place in Indian art tradition" (Kamath 2001, p115)

- ↑ Quote:"Of the city of Kalyana, situated in the north of Karnataka nothing is left, but a fabulous revival in temple building during the 11th century in central Karnataka testifies to the wealth during Kalyan Chalukya rule"(Foekema (1996), p14)

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p107

- ↑ From the 1142 and 1147 records, Kamath (2001), p108

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p139, part1; From the Chikkalagi records (Kamath 2001, p108)

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p140, part1; Kamath (2001) p109

- 1 2 Sen (1999), p498

- 1 2 Sen (1999), p499

- ↑ Vishnuvardhana made many military conquests later to be further expanded by his successors into one of the most powerful empires of South India—William Coelho. He was the true maker of the Hoysala kingdom—B.S.K. Iyengar in Kamath (2001), p124–126

- ↑ B.L.Rice in Kamath (2001), p123

- ↑ Keay (2000), p251

- ↑ Thapar (2003), p367

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p123

- ↑ Natives of south Karnataka (Chopra, 2003, p150 Part1)

- ↑ Shiva Prakash in Ayyappapanicker (1997), pp164, 203; Rice E. P. (1921), p59

- ↑ Kamath (2001), pp132–134

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p359, p361

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p427

- ↑ Sen (1999), pp500–501

- ↑ Foekema (1996), p14

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p124

- ↑ The most outstanding of the Hoysala kings according to Barrett and William Coelho in Kamath (2001), p126

- ↑ B.S.K. Iyengar in Kamath (2001), p126

- ↑ Keay (2000), p252

- ↑ Sen (1999), p500

- ↑ Two theories exist about the origin of Harihara I and his brother Bukka Raya I. One states that they were Kannadiga commanders of the Hoysala army and another that they were Telugu speakers and commanders of the earlier Kakatiya Kingdom (Kamath 2001, pp 159–160)

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p241

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p28, part2

- ↑ Indicated by records of the Ming dynasty (Kamath 2001, p162)

- ↑ Sastri (1955), p244

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p32, part2

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p32, part2; From the notes of Persian Abdur Razzak. Writings of Nuniz confirms that the kings of Burma paid tributes to Vijayanagara empire (Sastri 1955, p245)

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p164

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp37–39, part2; The notes of Portuguese Barbosa during the time of Krishnadevaraya confirms a very rich and well provided Vijayanagara city (Kamath 2001, p186)

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p177, part2; Art critic, Percy Brown calls Vijayanagar architecture a blossoming of Dravidian style–Kamath (2001), p182

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp171–173, part2; Kamath (2001), pp181–182

- ↑ Owing to his contributions to carnatic music, Purandaradasa is known as Karnataka Sangita Pitamaha.Dr. Jyotsna Kamat. "Purandara Dasa". Kamats Potpourri. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Madhusudana Rao CR. "Sri Purandara Dasaru". Dvaita Home Page. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ S. Sowmya, K. N. Shashikiran. "History of Music". Srishti's Carnatica Private Limited. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p174

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p53, part2; Kamath (2001), p190

- 1 2 Chopra (2003), pp56–57, part2; Kamath (2001), p191

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p57, part2; Kamath (2001), p192

- ↑ Sinha in Kamath (2001), p192

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p63, part2; Kamath (2001), p195

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp181–182, part2; Kamath (2001), p198

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p198

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p182, part2; Kamath (2001), p199

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p62, pp64–65, part2; Kamath (2001), p194

- 1 2 Kamath (2001), p200

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p201

- 1 2 Kamath (2001), p202

- ↑ Sinha in Kamath (2001), p2002

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p203

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p207

- ↑ Fergusson in Kamath (2001), p207

- ↑ Fergusson in Kamath (2001), p208

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p209

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p206

- ↑ Nagaraj in Pollock (2003), p370; Kamath (2001), p171, p174

- ↑ Subrahmanyam (2001), pp67–68; Kamath (2001), pp173–174

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p96, part2; Kamath (2006), pp173–174

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp101; Kamath (2006), p204

- ↑ Kamath (2001), p226

- ↑ Chopra (2003), p71, part3; Kamath (2001), p231–234

- ↑ Chopra (2003), pp80–81, part3

References

- Adiga, Malini (2006) [2006]. The Making of Southern Karnataka: Society, Polity and Culture in the early medieval period, AD 400–1030. Chennai: Orient Longman. ISBN 81-250-2912-5.

- Altekar, Anant Sadashiv (1934) [1934]. The Rashtrakutas And Their Times; being a political, administrative, religious, social, economic and literary history of the Deccan during C. 750 A.D. to C. 1000 A.D. Poona: Oriental Book Agency. OCLC 3793499.

- Chopra, P.N.; Ravindran, T.K.; Subrahmanian, N (2003) [2003]. History of South India (Ancient, Medieval and Modern) Part 1,2,3. New Delhi: Chand Publications. ISBN 81-219-0153-7.

- Foekema, Gerard (1996). A Complete Guide To Hoysala Temples. New Delhi: Abhinav. ISBN 81-7017-345-0.

- Hardy, Adam (1995) [1995]. Indian Temple Architecture: Form and Transformation-The Karnata Dravida Tradition 7th to 13th Centuries. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-312-4.

- Kamath, Suryanath U. (2001) [1980]. A concise history of Karnataka : from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Jupiter books. LCCN 80905179. OCLC 7796041.

- Keay, John (2000) [2000]. India: A History. New York: Grove Publications. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- Moraes, George M. (1990) [1931]. The Kadamba Kula, A History of Ancient and Medieval Karnataka. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0595-0.

- Nagaraj, D.R. (2003) [2003]. "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture". In Sheldon I. Pollock. Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1988]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi, Madras: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- Ramesh, K.V. (1984). Chalukyas of Vatapi. Delhi: Agam Kala Prakashan. ASIN B0006EHSP0. LCCN 84900575. OCLC 13869730. OL 3007052M.

- Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921]. Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0063-0.

- Reu, Pandit Bisheshwar Nath (1997) [1933]. History of the Rashtrakutas (Rathodas). Jaipur: Publication Scheme. ISBN 81-86782-12-5.

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A. (2002) [1955]. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. New Delhi: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2001). "Warfare and State Finance in Wodeyar Mysore". In Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. Penumbral Visions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 161–193. ISBN 978-0-472-11216-6.

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904). The Early History of India. The Clarendon press.

- Shiva Prakash, H.S. (1997). "Kannada". In Ayyappapanicker. Medieval Indian Literature:An Anthology. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-0365-0.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999) [1999]. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age Publishers. ISBN 81-224-1198-3.

- Thapar, Romila (2003) [2003]. The Penguin History of Early India. New Delhi: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-302989-4.