Political economy of climate change

Political economy of climate change is an approach that applies the political economy thinking of collective or political processes to study the critical issues surrounding the decision-making on climate change.

As the issue of climate change reaching the top of international agenda, the complexity of the environmental problems in combination with various other social political challenges have put great pressures on the scholars to explore a better understanding of the multiple actors and influencing factors that affect the climate change negotiation and to seek more effective solutions to tackle climate change. Analyzing these issues from a political economy perspective helps to explain the complex interactions between different stakeholders in respond to climate change impacts and provides broader opportunities to achieve better implementation of climate change policies.

Climate Change is first and foremost a political issue now that it has become a widely believed fact. Before tackling the issue, it is important to determine how drastic the effects can be in order to address it in an appropriate manner. When dealing with climate change, the inhabitants of countries must see themselves as “global citizens” rather than separate entities if any real long-term progress is to be made. In accordance with a global perspective, countries balance legislation regarding climate change in a way that benefits developing nations while refraining from discouraging developed nations from contributing to the effort.

Introduction

Background

Climate change and global warming have become one of the most pressing environmental concerns and the greatest global challenges in society today, despite the fact that a consensus has never been reached in the debates over its causes and consequences. As this issue continues to dominate the international agenda, researchers from different academic sectors have for long been devoting great efforts to explore effective solutions to climate change, with technologists and planners devising ways of mitigating and adapting to climate change; economists estimating the cost of climate change and the cost of tackling it; development experts exploring the impact of climate change on social services and public goods. However, Cammack (2007)[1] points out two problems with many of the above discussions, namely the disconnection between the proposed solutions to climate change from different disciplines; and the devoid of politics in addressing climate change at the local level. Further, the issue of climate change is facing various other challenges, such as the problem of elite-resource capture, the resource constraints in developing countries and the conflicts that frequently result from such constraints, which have often been less concerned and stressed in suggested solutions. In recognition of these problems, it is advocated that “understanding the political economy of climate change is vital to tackling it”.[1]

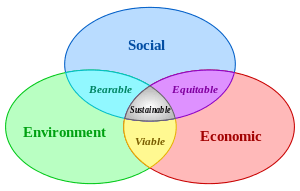

Meanwhile, the unequal distribution of the impacts of climate change and the resulting inequity and unfairness on the poor who contribute least to the problem have linked the issue of climate change with development study,[2][3] which has given rise to various programmes and policies that aim at addressing climate change and promoting development.[4][5] Although great efforts have been made on international negotiations concerning the issue of climate change, it is argued that much of the theory, debate, evidence-gathering and implementation linking climate change and development assume a largely apolitical and linear policy process.[6] In this context, Tanner and Allouche (2011) suggest that climate change initiatives must explicitly recognise the political economy of their inputs, processes and outcomes so as to find a balance between effectiveness, efficiency and equity.[6]

Definition

In its earliest manifestations, the term “political economy” was basically a synonym of economics,[7] while it is now a rather elusive term that typically refers to the study of the collective or political processes through which public economic decisions are made.[8] In the climate change domain, Tanner and Allouche (2011) define the political economy as “the processes by which ideas, power and resources are conceptualised, negotiated and implemented by different groups at different scales”.[6] While there have emerged a substantial literature on the political economy of environmental policy, which explains the “political failure” of the environmental programmes to efficiently and effectively protect the environment,[8] systematic analysis on the specific issue of climate change using the political economy framework is relatively limited.

Current Context: The Urgent Need for Political Economy

Characteristics of Climate Change

The urgent need to consider and understand the political economy of climate change is based on the specific characteristics of the problem.

The key issues include:

- The cross-sectoral nature of climate change: The issue of climate change usually fits into various sectors, which means that the integration of climate change policies into other policy areas is frequently called for.[9] Consequently, this has resulted in the highly complexity of the issue, as the problem needs to be addressed from multiple scales with diverse actors involved in the complex governance process.[10] The interaction of these facets leads to the political processes with multiple and overlapping conceptualisation, negotiation and governance issues, which requires the understanding of political economy processes.[6]

- The problematic perception of climate change as simply a “global” issue: Climate change initiatives and governance approaches have tended to be driven from the global scale. While the development of international agreements has witnessed a progressive step of global political action, this globally-led governance of climate change issue may be unable to provide adequate flexibility for specific national or sub-national conditions. Besides, from the development perspective of view, the issue of equity and global environmental justice would require a fair international regime within which the impact of climate change and poverty could be simultaneously prevented. In this context, climate change is not only a global crisis that needs the presence of international politics, but also a challenge for national or sub-national governments. The understanding of the political economy of climate change could explain the formulation and translation of international initiatives to specific national and sub-national policy context, which provides an important perspective to tackle climate change and achieve environmental justice.[6]

- The growth of climate change finance: Recent years have witnessed a growing number of financial flows and development of financing mechanisms in the climate change arena. The 2010 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico has committed significant amount of money from developed countries to developing world in supportive of the adaptation and mitigation technologies. In short terms, the fast start finance will be transferred through variety channels including bilateral and multilateral official development assistance, the Global Environment Facility and the UNFCCC.[11] Besides, a growing number of public funds have provided greater incentives to tackle climate change in developing countries. For instance, the Pilot Program for Climate Resilience aims at creating an integrated and scaled-up approach of climate change adaptation in some low-income countries and preparing for future finance flows. In addition, climate change finance in developing countries could potentially change the traditional aid mechanisms, through the differential interpretations of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ by developing and developed countries.[12] On the basis of equity and climate justice, climate change resource flows are increasingly called on developed world according to the culpability for damages.[13] As a result, it is inevitable to change the governance structures so as for developing countries to break the traditional donor-recipient relationships. Within these contexts, the understanding of the political economy processes of financial flows in climate change arena would be crucial to effectively governing the resource transfer and to tackling the climate change.[6]

- Different ideological worldviews of responding to climate change: Nowadays, because of the perception of science as a dominant policy driver, much of the policy prescription and action in climate change arena have concentrated on assumptions around standardised governance and planning systems, linear policy processes, readily transferable technology, economic rationality, and the ability of science and technology to overcome resource gaps.[14] As a result, there tends to be a bias towards technology-led and managerial approaches to address climate change in apolitical terms. Besides, a wide range of different ideological worldviews would lead to a high divergence of the perception of climate change solutions, which also has a great influence on decisions made in response to climate change.[15] Exploring these issues from a political economy perspective provides the opportunity to better understand the “complexity of politic and decision-making processes in tackling climate change, the power relations mediating competing claims over resources, and the contextual conditions for enabling the adoption of technology”.[6]

- Unintended negative consequences of adaptation policies that fail to factor in environmental-economic trade-offs: Successful adaptation to climate change requires balancing competing economic, social, and political interests. In the absence of such balancing, harmful unintended consequences can undo the benefits of adaptation initiatives. For example, efforts to protect coral reefs in Tanzania forced local villagers to shift from traditional fishing activities to farming that produced higher greenhouse gas emissions.[16]

Socio-political Constraints

The role of political economy in understanding and tackling climate change is also founded upon the key issues surrounding the domestic socio-political constraints:[1]

- The problems of fragile states: Fragile states—defined as poor performers, conflict and/or post-conflict states—are usually incapable of using the aid for climate change effectively. The issues of power and social equity have exacerbated the climate change impacts, while insufficient attention has been paid to the dysfunction of fragile states. Considering the problems of fragile states, the political economy approach could improve the understanding of the long-standing constraints upon capacity and resilience, through which the problems associated with weak capacity, state-building and conflicts could be better addressed in the context of climate change.

- Informal governance: In many poorly performing states, decision-making around the distribution and use of state resources is driven by informal relations and private incentives rather than formal state institutions that are based on equity and law. This informal governance nature that underlies in the domestic social structures prevents the political systems and structures from rational functioning and thus hinders the effective response towards climate change. Therefore, domestic institutions and incentives are critical to the adoption of reforms. Political economy analysis provides an insight into the underlying social structures and systems that determine the effectiveness of climate change initiatives (1).

- The difficulty of social change: Developmental change underdeveloped countries is painfully slow because of a series of long-tem collective problems, including the societies’ incapacity of working collectively to improve wellbeing, the lack of technical and social ingenuity, the resistance and rejection to innovation and change. In the context of climate change, these problems significantly hinder the promotion of climate change agenda. Taking a political economy view at the underdeveloped countries could help to understand and create incentives to promote transformation and development, which lays a foundation for the expectation of implementing a climate change adaptation agenda.

Research focuses and approaches

Brandt and Svendsen (2003)[17] introduce a political economy framework that based on the political support function model by Hillman (1982)[18] into the analysis of the choice of instruments to control climate change in the European Union policy to implement its Kyoto Protocol target level. In this political economy framework, the climate change policy is determined by the relative strength of stakeholder groups. By examining the different objective of different interest groups, namely industry groups, consumer groups and environmental groups, the authors explain the complex interaction between the choices of instrument for the EU climate change policy, specifically the shift from the green taxation to a grandfathered permit system.

A report by the Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (2011) takes a political economy approach to explain why some countries adopt climate change policies while others do not, specifically among the countries in the transition region.[19] This work analyzes the different political economy aspects of the characteristics of climate change policies so as to understand the likely factors driving climate change mitigation outcomes in many transition countries. The main conclusions are listed below:

- The level of democracy alone is not a major driver of climate change policy adoption, which means that the expectations of contribution to global climate change mitigation are not necessarily limited by the political regime of a given country.

- Public knowledge, shaped by various factors including the threat of climate change in a particular country, the national level of education and existence of free media, is a critical element in climate change policy adoption, as countries with the public more aware of the climate change causes are significantly more likely to adopt climate change policies. The focus should therefore be on promoting public awareness of the urgent threat of climate change and prevent information asymmetries in many transition countries.

- The relative strength of the carbon-intensive industry is a major deterrent to the adoption of climate change policies, as it partly accounts for the information asymmetries. However, the carbon-intensive industries often influence government’s decision-making on climate change policy, which thus calls for a change of the incentives perceived by these industries and a transition of them to a low-carbon production pattern. Efficient means include the energy price reform and the introduction of international carbon trading mechanisms.

- The competitive edge gained national economies in the transition region in a global economy, where increasing international pressure is put to reduce emissions, would enhance their political regime’s domestic legitimacy, which could help to address the inherent economic weaknesses underlying the lack of economic diversification and global economic crisis.

Tanner and Allouche (2011)[6] propose a new conceptual and methodological framework for analysing the political economy of climate change in their latest work, which focuses on the climate change policy processes and outcomes in terms of ideas, power and resources. The new political economy approach is expected to go beyond the dominant political economy tools formulated by international development agencies to analyse climate change initiatives[20][21][22] that have ignored the way that ideas and ideologies determine the policy outcomes (see table).[23] The authors assume that each of the three lenses, namely ideas, power and resources, tends to be predominant at one stage of the policy process of the political economy of climate change, with “ideas and ideologies predominant in the conceptualisation phase, power in the negotiation phase and resource, institutional capacity and governance in the implementation phase”.[6] It is argued that These elements are critical in the formulation of international climate change initiatives and their translation to national and sub-national policy context.

| Issue | Dominant approach | New political economy |

|---|---|---|

| Policy process | Linear, informed by evidence | Complex, informed by ideology, actors and power relations |

| Dominant scale | Global and inter-state | Translation of international to national and sub-national level |

| Climate change science and research | Role of objective science in informing policy | Social construction of science and driving narratives |

| Scarcity and poverty | Distributional outcomes | Political processes mediating competing claims for resources |

| Decision-making | Collective action, rational choice and rent seeking | Ideological drivers and incentives, power relations |

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Cammack, D. (2007) Understanding the political economy of climate change is vital to tackling it, Prepared by the Overseas Development Institute for UN Climate Change Conference in Bali, December 2007.

- ↑ Adger, W.N., Paavola, Y., Huq, S. and Mace, M.J. (2006) Fairness in Adaptation to Climate Change, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- ↑ Tol, R.S.J.; Downing, T.E.; Kuik, O.J.; Smith, J.B. (2004). "Distributional Aspects of Climate Change Impacts". Global Environmental Change. 14: 259–72. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2004.04.007.

- ↑ IEA, UNDP and UNIDO (2010) Energy Poverty: How to Make Modern Energy Access Universal?, special early excerpt of the World Energy Outlook 2010 for the UN General Assembly on the Millennium Development Goals, Paris: OECD/IEA.

- ↑ Nabuurs, G.J., Masera, O., Andrasko, K., Benitez-Ponce, P., Boer, R., Dutschke, M., Elsiddig, E., Ford-Robertson, J., Frumhoff, P., Karjalainen, T., Krankina, O., Kurz, W.A., Matsumoto, M., Oyhantcabal, W., Ravindranath, N.H., Sanz Sanchez, M.J. and Zhang, X. (2007) ‘Forestry’, in: Mitigation of Climate Change, Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 6. Tanner, T. and Allouche, J. (2011) 'Towards a New Political Economy of Climate Change and Development', IDS Bulletin Special Issue: Political Economy of Climate Change, 42(3): 1-14.

- ↑ Groenewegen, E.(1987) 'Political economy and economics', in: Eatwell J. et al., eds., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Vol.3: 904-907, Macmillan & Co., London.

- 1 2 Oates, W.E.and Portney, P.R.(2003) 'The political economy of environmental policy', in: Handbook of Environmental Economics, chapter 08: p325-54

- ↑ OECD (2009) Policy Guidance on Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into Development Co-operation, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris.

- ↑ Rabe, B.G. (2007). "Beyond Kyoto: Climate Change Policy in Multilevel Governance Systems". Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions. 20 (3): 423–44. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00365.x.

- ↑ Harmeling, S. and Kaloga, A. (2011)'Understanding the Political Economy of the Adaptation Fund', IDS Bulletin Special Issue: Political Economy of Climate Change, 42(3): 23-32

- ↑ Okereke, C (2008). "Equity Norms in Global Environmental Governance". Global Environmental Politics. 8 (3): 25–50. doi:10.1162/glep.2008.8.3.25.

- ↑ Abdullah, A., Muyungi, R., Jallow, B., Reazuddin, M. and Konate, M. (2009) National Adaptation Funding: Ways Forward for the Poorest Countries, IIED Briefing Paper, International Institute for Environment and Development, London.

- ↑ Leach, M., Scoones, I. and Stirling, A. (2010), Dynamic Sustainabilities–Technology, Environment, Social Justice, London: Earthscan.

- ↑ Carvalho, A (2007). "Ideological Cultures and Media Discourses on Scientific Knowledge: Re-reading News on Climate Chang". Public Understanding of Science. 16 (2): 223–43. doi:10.1177/0963662506066775.

- ↑ Editorial (November 2015). "Adaptation trade-offs" (PDF). Nature Climate Change. 5: 957. doi:10.1038/nclimate2853. Retrieved 30 March 2016. See also Sovacool, B. and Linnér, B.-O. (2016), The Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation, Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- ↑ Brandt, U.S. and Svendsen, G.T. (2003) The Political Economy of Climate Change Policy in the EU: Auction and Grandfathering, IME Working Papers No. 51/03.

- ↑ Hillman, A.L. (1982). "Declining industries and political-support protec-tionist motives". The American Economic Review. 72: 1180–7.

- ↑ EBRD (2011) 'Political economy of climate change policy in the transition region', in: Special Report on Climate Change: The Low Carbon Transition, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Chapter Four.

- ↑ DFID (2009) Political Economy Analysis: How to Note, DFID Practice Paper, Department for International Development, London.

- ↑ World Bank (2009) Problem-Driven Governance and Political Economy Analysis: Good Practice Framework, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- ↑ World Bank (2004) Operationalizing Political Analysis: The Expected Utility Stakeholder Model and Governance Reforms, PREM Notes 95, World Bank, Washington D.C.

- ↑ Barnett, M.N. and Finnemore, M. (2004) Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics, Cornell University Press, New York.