Poles in Lithuania

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 200,317 [1] | |

| Languages | |

| Russian, Polish, Lithuanian | |

| Religion | |

| 88.6 percent Roman Catholic per 2011 census[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Poles, Lithuanians, Belarusians |

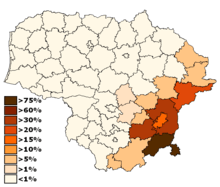

The Polish minority in Lithuania numbered 200,317 persons, according to the Lithuanian census of 2011, or 6.6% of the total population of Lithuania. It is the largest ethnic minority in the country and the second largest Polish diaspora group among the post-Soviet states. Poles are concentrated in the Vilnius Region.

People of Polish ethnicity have lived in the territory of modern Lithuania for many centuries. The relationship between the two groups has been long and complex. Their countries were united during the era of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, but both nations lost their independence after the Commonwealth was partitioned in the late 18th century. Both nations regained their independence in the wake of World War I, but hostilities over the ownership of Vilnius and the surrounding region broke out in 1920. The disputes became politically moot after the Soviet Union exercised its authority over both countries during and immediately after World War II. Some tensions over the Vilnius Region resurfaced after Lithuania regained its independence in 1990,[3][4] but have since remained at manageable levels. Poland was highly supportive of Lithuanian independence, and became one of the first countries to recognise independent Lithuania, despite apprehensions over Lithuania's treatment of its Polish minority.[5][6][7]

Statistics

According to the Lithuanian census of 2011, the Polish minority in Lithuania numbered 200,317 persons, or 6.6% of the population of Lithuania. It is the largest ethnic minority in modern Lithuania, the second largest being the Russian minority. Poles are concentrated in the Vilnius region. The vast majority of Poles live in Vilnius county (185,912 people, or 24% of the county's population); Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, has 88,408 Poles, or 16.5% of the city's population. Especially large Polish communities are found in Vilnius district municipality (52% of the population) and Šalčininkai district municipality (77.75%).

Lithuanian municipalities with Polish minority exceeding 1% of the total population (according to the 2011 census) are listed in the table below:

| Municipality name | County | Total population | Number of ethnic Poles | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Druskininkai municipality | 21,803 | 755 | 3.46% | |

| Varėna district municipality | 25,377 | 1,612 | 6.35% | |

| Jonava district municipality | 46,519 | 542 | 1.16% | |

| Kaišiadorys district municipality | 33,786 | 351 | 1.03% | |

| Ignalina district municipality | 18,386 | 1,297 | 7.05% | |

| Molėtai district municipality | 20,700 | 1,313 | 6.34% | |

| Zarasai district municipality | 18,390 | 1,082 | 5.88% | |

| Vilnius city municipality | 535,631 | 88,408 | 16.50% | |

| Elektrėnai municipality | 24,975 | 1,769 | 7.08% | |

| Šalčininkai district municipality | 34,544 | 26,858 | 77.75% | |

| Širvintos district municipality | 17,571 | 1,628 | 9.26% | |

| Švenčionys district municipality | 27,868 | 7,239 | 25.97% | |

| Trakai district municipality | 34,411 | 10,362 | 30.11% | |

| Vilnius district municipality | 95,348 | 49,648 | 52.07% |

Languages

Out of the 234,989 Poles in Lithuania, 187,918 (80.0%) consider the Polish language to be their first language. 22,439 Poles (9.5%) speak Russian as their first language, while 17,233 (7.3%) speak Lithuanian. 6,279 Poles (2.7%) did not indicate their first language. The remaining 0.5% speak various other languages.[9]

Historical demographics

| Population with Polish ethnic affiliations [10][11] within current Lithuanian borders | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census year | 1897 | 1923 est. | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2001 | 2007 est. | 2008 est. | 2009 est. | 2010 est. | 2011[12] |

| Population | 260,000 | 415,000 | 230,000 | 240,200 | 247,000 | 258,000 | 235,000 | 212,100 | 208,300 | 205,500 | 201,500 | 200,317 |

| Percentage | 9.7% | 15.3% | 8.5% | 7.7% | 7.3% | 7.0% | 6.7% | 6.3% | 6.2% | 6.1% | 6.0% | 6.6% |

| Percentage of Poles in Lithuania stating Polish as their mother tongue [13] (censuses data) | ||||||||||||

| Census year | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | 2001 | 2011 | ||||||

| Percentage | 96.8% | 92.4% | 88.3% | 85.0% | 80.0% | 79.0% | ||||||

Estimates based on the data of the central database of the Residents’ Register Service under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Lithuania: 201,500 or 6.0% (1 January 2010) and 212,800 or 6.6% (1 January 2011). Increase of Poles number and share was caused by the reduction of so-called "not indicated" ethnicity in the Residents’ Register.[14]

Education

| Absolute numbers with Polish language education at Lithuanian rural schools (1980)[15] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| District municipality | Lithuanian | Russian | Polish |

| Vilnius / Wilno | 1250 | 4150 | 6400 |

| Šalčininkai / Soleczniki | 500 | 2050 | 3200 |

| Švenčionys / Święciany | 1350 | 600 | 100 |

| Trakai / Troki | 2900 | 50 | 950 |

| Varėna / Orany | 6000 | 0 | 50 |

| Širvintos / Szyrwinty | 2400 | 100 | 100 |

| Absolute number with Polish language education at Lithuanian urban schools was 5 600 | |||

As of 1980, about 20% of Polish Lithuanian students chose Polish as the language of instruction at school.[15] In the same year, about 60-70% of rural Polish community chose Polish. However, even in towns with predominantly Polish population the share of Polish language education was less than the percentage of Poles. Even though, historically, Poles tended to strongly oppose Russification, one of the most important reasons to choose Russian language education was the absence of Polish language college and university learning in the USSR, and during Soviet times Polish minority students in Lithuania were not allowed to get college/university education across the border in Poland. Only in 2007, the first small branch of the Polish University of Białystok opened in Vilnius. In 1980 there were 16,400 school students instructed in Polish. Their number declined to 11,400 in 1990. In independent Lithuania between 1990 and 2001 the number of Polish mother tongue children attending schools with Polish as the language of instruction doubled to over 22,300, then gradually decreased to 18,392 in 2005.[16] In September 2003, there were 75 Polish-language general education schools and 52 which provided education in Polish in combination of languages (for example Lithuanian-Polish, Lithuanian-Russian-Polish). These numbers fell to 49 and 41 in 2011, reflecting a general decline in the number of schools in Lithuania.[17] Polish government was concerned in 2015 about the education in Polish.[18]

History

People of Polish ethnicity have lived in Lithuania for many centuries. Many Poles in Lithuania today are the descendants of Polonized Lithuanians or Ruthenians.[19] Historically, the number of Poles in modern Lithuanian territory has varied during different periods. Polish culture began to influence the Grand Duchy of Lithuania around the time of the Union of Lublin (16th century), and during the time of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795) much of the Lithuanian nobility was Polonized and joined the Polish-Lithuanian szlachta class. Reformation gave another impetus to the spread of the Polish language, as the Bible and other religious texts were translated from Latin to Polish. In 1697 Polish replaced Ruthenian as a chancellery language. In the 19th century peasants of Polish nationality started to appear in Lithuania, mostly by Polonization of Lithuanian peasants[20] in Dzūkija and to a lesser degree in Aukštaitija.

A large portion of the Vilnius area was controlled by the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period, particularly the area of the Republic of Central Lithuania, which had a significant Polish speaking population. For example, the Wilno Voivodeship (25% of it is a part of modern Lithuania and 75% - modern Belarus) in 1931 contained 59.7% Polish speakers and only 5.2% Lithuanian speakers;[21] see Ethnic history of the region of Vilnius for details. From 1918 to 1921 there were several conflicts, such as the activity of the Polish Military Organization, Sejny uprising (that was met with massive outrage in Lithuania[22]) and a discovered attempt at a Polish coup on the Lithuanian government.[23][24] From the documents stolen from Polish Military Organization headquarters safe in Vilnius and given to Prime Minister of Lithuania Augustinas Voldemaras, it is clear that this plot was directed by Józef Piłsudski himself.[25] The Polish-Lithuanian War and Żeligowski's Mutiny contributed to a worsening of Polish-Lithuanian relations; increasingly Polish people were viewed with suspicion in Lithuania. The loss of Vilnius was a stunning blow to Lithuanian aspirations and identity, and the unrelenting irredentist demand for its return became one of the most important elements of Lithuanian political and social life in the interwar period.[26] The irredentist campaign resulted in the emergence of feelings of hatred and revenge directed against the Poles in the Lithuanian society.[26] In fact, the largest social organization in interwar Lithuania was the League for the Liberation of Vilnius (Vilniaus Vadavimo Sąjunga, or VVS), which propagated irredentist views in its magazine "Our Vilnius" (Mūsų Vilnius)." [26]

Hence, in the interwar period, the Polish minority was persecuted by the administration of independent Lithuania.[27] The Lithuanian census of 1923 showed that Poles constituted 65,600 Lithuania inhabitants (3.2% of total population).[28] In interwar Lithuania, people declaring Polish ethnicity were officially described as Polonized Lithuanians who merely needed to be re-Lithuanized, Polish-owned land was confistacted, and Polish religious services, schools, publications, and voting rights were restricted.[29] After the establishment of Valdemaras regime in 1926, Polish schools were closed, many Poles were incarcerated, and Polish newspapers were placed under strict censorship.[30]

During the World War II expulsions and shortly after the war, the Soviet Union, during its struggle to establish the People's Republic of Poland, forcibly resettled many Poles, who lived in the Lithuanian SSR and were seen as enemies of the state, into Siberia. After the war, in 1945-1948, the Soviet Union allowed 197,000 Poles to leave to Poland; in 1956-1959, another 46,600 were able to leave.[31][32] In the 1950s the remaining Polish minority was a target of several attempted campaigns of Lithuanization by the Communist Party of Lithuania, which tried to ban any teaching in the Polish language; those attempts, however, were vetoed by Moscow, which saw them as too nationalistic.[33] The Soviet census of 1959 showed 230,100 Poles concentrated in the Vilnius region (8.5% of the Lithuanian SSR's population).[34] The Polish minority increased in size, but more slowly than other ethnic groups in Lithuania; the last Soviet census of 1989 showed 258,000 Poles (7.0% of the Lithuanian SSR's population).[34] The Polish minority, subject in the past to massive, often voluntary [35] Russification and Sovietization, and recently to mostly voluntary processes of Lithuanization, shows many and increasing signs of assimilation with Lithuanians.[34] However, some young Poles don't speak Lithuanian fluently, so they prefer to study in Poland or in the Polish language University of Białystok branch in Vilnius, rather than in Lithuanian universities.

Most of Poles who live southwards of Vilnius speak a dialect of Polish, that contains many substratical relics from Lithuanian and Belarusian.[36]

In independent Lithuania

The situation of the Polish minority in Lithuania has caused occasional tensions in Polish-Lithuanian relations during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. When Lithuania declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev sought help from the Polish minority.[37][38] The Polish minority, still remembering the 1950s attempts to ban the Polish language,[33] was much more supportive of the Soviet Union and afraid that the new Lithuanian government might want to reintroduce the Lithuanisation policies.[33] A pro-Moscow anti-independence movement similar to Internationalist movements in Latvia and Estonia was formed in 1989, called the Unity. The organization was supported by many Poles of Lithuania, making it perhaps more popular with the Polish minority than with the Russophone minority of Lithuania.[39] This might have surprised the Poles of Warsaw, then seeking a de-communization in Poland and declaring the question of Polish minority in Lithuania an internal matter of Lithuania. The pro-Moscow stance of some leading Poles of Lithuania compromised at times the activities of more Lithuania-friendly Poles. At the election to the Soviet Congress of People's Deputies, two Poles (one of them Jan Ciechanowicz) were elected to that body, both pro-Moscow.

According to surveys conducted in the spring of 1990, 47% of Poles in Lithuania supported the pro-Soviet Communist party (in contrast to 8% support among ethnic Lithuanians), while 35% supported Lithuanian independence.[33] The regional authorities in Vilnius and Šalčininkai region, under Polish leadership, with support from Soviet authorities, argued for the establishment of an autonomous region in South Eastern Lithuania, a request that was declined by the Lithuanian government and left lasting resentment among some residents.[38][40] The same Polish regional leaders later voiced support for the Soviet coup attempt of 1991 in Moscow.[40] The Government of Poland, however, never supported the autonomist tendencies of the Polish minority in Lithuania.

Current tensions arise regarding Polish education and spelling of names. The United States Department of State stated, in a report issued in 2001, that the Polish minority had issued complaints with regard to its status in Lithuania, and that members of the Polish Parliament criticized the government of Lithuania over alleged discrimination against the Polish minority.[41] In recent years, the Lithuanian government budgets 40,000 litas (~$15,000) for the needs of the Polish minority (out of the 7 million litas budget of the Department of National Minorities).[42] In 2006 Polish Foreign Minister Stefan Meller asserted that Polish educational institutions in Lithuania are severely underfunded.[43] Similar concerns were voiced in 2007 by a Polish parliamentary commission.[44] According to a report issued by the European Union Fundamental Rights Agency in 2004, Poles in Lithuania were the second least-educated minority group in Lithuania.[45] The branch of the University of Białystok in Vilnius educates mostly members of the Polish minority.

A report by the Council of Europe, issued in 2007, stated that on the whole, minorities were integrated quite well into the everyday life of Lithuania. The report expressed a concern with Lithuanian nationality law, which contains a right of return clause.[46] The citizenship law was under discussion during 2007; it was deemed unconstitutional on 13 November 2006.[47] A proposed constitutional amendment would allow the Polish minority in Lithuania to apply for Polish passports.[48] Several members of the Lithuanian Seimas, including Gintaras Songaila and Andrius Kubilius, publicly stated that two members of the Seimas who represent Polish minority there (Waldemar Tomaszewski and Michal Mackiewicz) should resign, because they accepted the Karta Polaka.[49]

Lithuanian constitutional law stipulates that everyone (not only Poles) who has Lithuanian citizenship and resides within the country has to Lithuanianise their name (i.e. spell it in the Lithuanian phonetics and alphabet); for example, the name Kleczkowski has to be spelled Klečkovski in official documents.[50][51][52][53] On April 24, 2012 the Europarliament accepted for further consideration the petition (number 0358/2011) submitted by a Tomasz Snarski about the language rights of Polish minority, in particular about enforced Lithuanization of Polish surnames.[54][55]

Representatives of the Lithuanian government demanded removal of Polish names of the streets in Maišiagala (Mejszagoła), Raudondvaris (Czerwony Dwór), Riešė (Rzesza) and Sudervė (Suderwa)[56][57] as by constitutional law all names have to be in Lithuanian. Tensions have been reported between the Lithuanian Roman Catholic clergy and its Polish parishioniers in Lithuania.[58][59][60] The Seimas voted against foreign surnames in Lithuanian passports.[61]

The situation is further escalated by extremist groups on both sides. Lithuanian extremist nationalist organization Vilnija[38][62][63][64] seeks the Lithuanisation of ethnic Poles living in the Eastern part of Lithuania.[33] The former Polish ambassador to Lithuania, Jan Widacki, has criticised some Polish organizations in Lithuania as being far-right and nationalist.[65] Jan Sienkiewicz has criticized Jan Widacki.[66]

In late May 2008, the Association of Poles in Lithuania issued a letter, addressed to the government of Lithuania, complaining about anti-minority (primarily, anti-Polish) rhetoric in media, citing upcoming parliamentary elections as a motive, and asking for better treatment of the ethnic minorities. The association has also filed a complaint with the Lithuanian prosecutor, asking for investigation of the issue.[67][68][69]

Lithuania has not ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[70] 60,000 Poles have signed a petition against an education system reform. A school strike was declared and suspended.[71]

The Law on Ethnic Minorities lapsed in 2010.[72]

In 2014 Šalčininkai district municipality administrative director Bolesław Daszkiewicz was fined about 12 500 Euro for failure to execute a court ruling to remove Lithuanian-Polish street signs.[73] Lucyna Kotłowska was fined about 1738 Euro.[74]

Culture

Surnames

The surnames of Lithuanian Poles that are of Polish forms, many of them ending in suffixes -e/owski, -e/owicz, rarer -(ń)ski, and more rare -cki (Lithuanian spelling -e/ovski, -e/ovič, -(n)ski, -cki), are commonly the same as their counterparts in Poland and usually have cognates among Lithuanian surnames, which reflects the historical living in the common cultural area, ethnic, cultural, or linguistic assimilation, and common use of the same Slavic patronymic suffixes: Pol. -e/owski and -e/owicz, Lith. -(i)auskas and -e/avičius, and Belarusian -оўскі and -e/овіч. The suffixes -e/owski, -(ń)ski, and -cki are historically characteristic of Polish names and -e/ovič of Belarusian names. Surnames ending with -e/ovič, which is more frequent among Lithuanians (-e/-avičius), Belarusians, and Lithuanian Poles, is rarer in Poland.

The frequency of Lithuanian-specific surnames among the surnames of Lithuanian Poles is moderate. The sketchy examples[75][76] include anthroponyms of two roots — Talmont, Narvoiš, Bowgerd, Dowgiało, Golmont, Žybort, etc. — with Lithuanian patronymic suffixes – Pieciun, Wickun, Mikalajun, Masojć, Matulaniec — with Lithuanian diminutive suffixes − Jurgiel, Wierbiel, Banel, Jusel, Drawnel, Rekiel, Szuksztul — Lithuanian root — Garszwo, Plokszto, Pażuś, Gejgall, Szyllo, Wojsznis — Lithuanian root with a Slavic suffix — Mieżewicz, Pażusińskaja, Błaszkiewicz, Balsewicz, Dajnowicz, Tarejkowicz, Narkiewicz.

Measuring the historical ethnic "charge" of a surname has certain specific features, as, for example, there were many surnames made from the same Christian names and Slavic-form suffixes used by Lithuanian, Belarusian, and Polish speakers. Surnames could also be made from a Lithuanian root and a Slavic suffix, a Belarusian-characteristic root and a Polish-characteristic suffix, and so on.

Name/surname spelling

The official spelling of the Polish (and any other non-Lithuanian) name in person's passport is governed by the 31 January 1991 Resolution of the Supreme Council of Lithuania No. I-1031 "Concerning name and surname spelling in the passport of the citizen of the Republic of Lithuania". There are the following options. The law says, in part:[77]

2. In the passport of the citizen of the Republic of Lithuania, the name and surname of the persons of non-Lithuanian origin shall be spelt in the letters of the Lithuanian language. On the citizen's request in writing, the name and surname can be spelt in the order established as follows:

a) according to pronunciation and without grammatisation (i.e. without Lithuanian endings) or b) according to pronunciation alongside grammatisation (i.e. adding Lithuanian endings).

3. The names and surnames of the persons, who have already possessed citizenship of other State, shall be written according to the passport of the State or an equivalent document available in the passport of the Republic of Lithuania on its issue.

This resolution was challenged in 1999 in the Constitutional Court upon a civil case of a person of Polish ethnicity who requested his name to be enters in the passport in Polish language. The Constitutional Court upheld the 1991 resolution. At the same time it was stressed out citizen's rights to spell their name whatever they like in areas "not linked with the sphere of use of the state language pointed out in the law".[78]

Organizations

Poles in Lithuania are organized into several groups and associations.

The Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania (Lithuanian: Lietuvos lenkų rinkimų akcija, Polish: Akcja Wyborcza Polaków na Litwie) is an ethnic minority-based political party formed in 1994, able to exert significant political influence in the administrative districts where Poles form a majority or significant minority. This party has held 1-2 seats in the parliament of Lithuania for the past decade; in the last general elections it got about 4% of votes. The party is more active in local politics and controls several municipal councils.[79] It cooperates with other minorities, mainly the Lithuanian Russian Union.

The Association of Poles in Lithuania (Polish: Związek Polaków na Litwie) is an organization formed in 1989 to bring together Polish activists in Lithuania. It numbers between 6,000 and 11,000 members. It defends the civil rights of the Polish minority and engages in educational, cultural, and economic activities.[79]

Prominent Poles

Prior to 1940

- Gabriel Narutowicz - president of Poland

- Józef Piłsudski - Polish statesman

- Wiktor Budzyński - politician

- Kanuty Rusiecki - painter

- Michał Pius Römer - lawyer

- Sofija Pšibiliauskienė - writer (Polish: Zofia Przybylewska)

- Marija Lastauskienė - writer (Polish: Maria Lastowska)

- Medard Czobot - politician (Lithuanian: Medardas Čobotas)

Today

- Anicet Brodawski - a Polish autonomist leader during the late 1980s

- Darjuš Lavrinovič (Polish: Dariusz Ławrynowicz) - basketball player

- Kšyštof Lavrinovič (Polish: Krzysztof Ławrynowicz) - basketball player

- Artur Liudkovski (Polish: Artur Ludkowski) - former deputy mayor of Vilnius

- Jarosław Niewierowicz (Lithuanian: Jaroslav Neverovič) - former minister of energy, former vice-minister of foreign affairs

- Czesław Okińczyc (Lithuanian: Česlav Okinčic) - politician, journalist

- Artur Płokszto (Lithuanian: Artur Plokšto) - secretary of Ministry of National Defence

- Leokadia Poczykowska (Lithuanian: Leokadija Počikovska) - politician

- Ewelina Saszenko (Lithuanian: Evelina Sašenko) - singer

- Jan Sienkiewicz (Lithuanian: Jan Senkevič) - politician, journalist

- Valdemar Tomaševski (Polish: Waldemar Tomaszewski) - leader of Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania

- Stanisław Widtmann (Stanislavas Vidtmannas) - (as of 2011) vice-minister of culture in ethnic minorities affairs.[80][81]

- Jarosław Wołkonowski - dean of branch of University of Białystok in Vilnius

- Alina Orłowska - singer (Lithuanian: Alina Orlova)

- Michał Mackiewicz - politician (Lithuanian: Michal Mackevič)

- Irena Litwinowicz - politician (Lithuanian: Irena Litvinovič)

- Zbigniew Balcewicz - politician (Lithuanian: Zbignev Balcevič)

See also

References

- ↑ Lithuania Census 2011

- ↑ "Population by religious community to which they attributed themselves and ethnicity". Department of Statistics (Lithuania). Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ↑ Evaldas Nekrasas. "Is Lithuania a Northern or Central European Country?" (PDF). Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review. p. 5. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

In a letter written to Vytautas Landsbergis in December of 1991, Polish President Lech Walesa described Lithuanian-Polish relations as "close to critical."

- ↑ Antanas Valionis; Evaldas Ignatavièius; Izolda Brièkovskienë. "From Solidarity to Partnership: Lithuanian-Polish Relations 1988-1998" (PDF). Lithuanian Foreign Policy Review, 1998, issue 2. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

The interval between the restoration of diplomatic relations in September 1991 and the signing of the Treaty on Friendly Relations and Good Neighborly Cooperation on April 26, 1994 was probably the most difficult period for Lithuanian-Polish relations (there were even assertions that relations in this period were "in some ways even worse than before the war").

- ↑ George Sanford, "Poland: the conquest of history", Taylor & Francis, 1999, pg. 99

- ↑ A. T. Lane, "Lithuania: Stepping Westward", Routledge, 2001, pg. 209

- ↑ Stephen R. Burant and Voytek Zubek, Eastern Europe's Old Memories and New Realities: Resurrecting the Polish-Lithuanian Union, East European Politics and Societies 1993; 7; 370, online

- ↑ Source: Population by some ethnicities by county and municipality

- ↑ Population by ethnicity and mother tongue. Data from Statistikos Departamentas, 2001 Population and Housing Census.

- ↑ Atlas of Lithuanian SSR, Moscow, 1981 (in Russian), p.129

- ↑ Data from Statistikos Departamentas Accessed 2009-08-09

- ↑ Lithuania Census 2011 p. 47.

- ↑ Mercator - Education information, documentation, research. The Polish language education in Lithuania see: graph on p.12 (PDF file, 2.2 MB) Accessed 2008-01-16.

- ↑ Yearbook 2010. Lietuvos Statistikos departamentas, 2011. p. 47.

- 1 2 "Атлас Литовской ССР" 1981, Государственный плановый комитет Литовской ССР. Министерство высшего и среднего специального образования Литовской ССР. Главное управление геодезии и картографии при Совете Министров СССР. Москва 1981.

- ↑ Mercator - Education information, documentation, research. The Polish language education in Lithuania see: graph on p.16 (PDF file, 2.2 MB) Accessed 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Arvydas Matulionis et al.The Polish Minority in Lithuania. ENRI-East Research Report #8. 2011. p. 18.

- ↑ The meeting of deputy ministers of education - Poland-Lithuania

- ↑ Walter C. Clemens (1991). Baltic Independence and Russian Empire. St. Martin's Press. p. 150. ISBN 0-312-04806-8.

In reality, many Poles in Lithuania were the offspring of Polonized Lithuanians or Belarussians.

- ↑ Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia Vol. 11. 2007.

- ↑ "Drugi Powszechny Spis Ludności z dnia 9 XII 1931 r". Statystyka Polski (in Polish). D (34). 1939.

- ↑ Editors: Gintautas Surgailis; Algirdas Ažubalis; Grzegorz Blaszyk; Pranas Jankauskas; Eriks Jekabsons; Waldemar Rezmer; et al. (2003). Karo archyvas XVIII (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. pp. 188–189. ISSN 1392-6489.

- ↑ Juozas, Rainys (1936). P.O.W. : (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa) Lietuvoje. Kaunas: Spaudos fondas. p. 184.

- ↑ Julius, Būtėnas; Mečys Mackevičius (1995). Mykolas Sleževičius: advokatas ir politikas. Vilnius: Lietuvos rašytojų sąjungos leidykla. p. 263. ISBN 9986-413-31-1.

- ↑ Lesčius, Vytautas (2004). Lietuvos kariuomenė nepriklausomybės kovose 1918-1920. Vilnius: Vilnius University, Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija. p. 269. ISBN 9955-423-23-4.

- 1 2 3 Michael MacQueen, The Context of Mass Destruction: Agents and Prerequisites of the Holocaust in Lithuania, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Volume 12, Number 1, pp. 27-48, 1998,

- ↑ Fearon, James D.; Laitin, David D. (2006). "Lithuania" (PDF). Stanford University. p. 4. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

The nationalizing Lithuanian state took measures to confiscate Polish owned land. It also restricted Polish religious services, schools, Polish publications, Polish voting rights. Poles were often referred to in the press in this period as the "lice of the nation".

- ↑ The number does not include Vilnius and Klaipėda regions. Census of 1923 was the only census carried out in Lithuania during the interwar period. Vaitiekūnas, Stasys (2006). Lietuvos gyventojai: Per du tūkstantmečius (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 189. ISBN 5-420-01585-4.

- ↑ Fearon, James D.; Laitin, David D. (2006). "Lithuania" (PDF). Stanford University. p. 4. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

Lithuanian nationalists resented demands by Poles for greater cultural autonomy (similar to that granted to the Jewish minority), holding that most of Lithuania's Poles were really deracinated Lithuanians who merely needed to be re-Lithuanianized. Resentments were exacerbated when Lithuanian Poles expressed a desire to "re-unite" the country with Poland. As a result, the nationalizing Lithuanian state took measures to confiscate Polish owned land. It also restricted Polish religious services, schools, Polish publications, Polish voting rights. Poles were often referred to in the press in this period as the "lice of the nation"

- ↑ Richard M. Watt. (1998). Bitter glory: Poland and its fate, 1918-1939. Hippocrene Books. p. 255.

- ↑ Eberhardt, Piotr. "Liczebność i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na Litwie (Numbers and distribution of Polish population in Lithuania)" (in Polish). Retrieved 2008-06-02.

Było to już po masowej "repatriacji" Polaków z Wileńszczyzny, która w latach 1945-1948 objęła 197 tys. Polaków (w tym z Wilna - 107,6 tys.) oraz kolejnej z lat 1956-1959, która umożliwiła wyjazd do Polski 46,6 tys. osób narodowości polskiej.

- ↑ Stravinskienė, Vitalija (2004). "Poles In Lithuania From The Second Half Of 1944 Until 1946: Choosing Between Staying Or Emigrating To Poland (English Summary)". Lietuvos istorijos metraštis. 2. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dovile Budryte (2005). Taming Nationalism?: Political Community Building in the Post-Soviet Baltic States. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 147–148. ISBN 0-7546-3757-3.

- 1 2 3 Eberhardt, Piotr. "Liczebność i rozmieszczenie ludności polskiej na Litwie (Numbers and distribution of Polish population in Lithuania)" (in Polish). Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ Fearon, James D.; Laitin, David D. (2006). "Lithuania" (PDF). Stanford University. p. 4. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

For example, in Vilnius where in the Soviet years education in Polish was offered by some 13–14 schools, only 25 percent of the children born to monoethnic Polish families attended Polish schools. Fifty percent of them chose Russian schools, and only 10 per cent Lithuanian schools.

- ↑ Valerijus Čekmonas, Laima Grumadaitė Kalbų paplitimas rytų Lietuvoje (The distribution of the languages in the east of Lithuania) in Lietuvos rytai; straipsnių rinkinys (The east of Lithuania; the collection of the articles) Vilnius 1993; p. 132; ISBN 9986-09-002-4

- ↑ Lithuania. Stanford University, 2006

- 1 2 3 Understanding Ethnic Violence: Fear, Hatred, and Resentment in Twentieth-century Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-521-00774-7, Roger Dale Petersen, Google Print, p.153

- ↑ Van Horne, Winston A (1997). "Global convulsions: Race, ethnicity, and nationalism at the end of the twentieth century". ISBN 978-0-7914-3235-8.

- 1 2 Robert G. Moser (2005). Ethnic Politics After Communism. Aldershot: Cornell University Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-8014-7276-8.

- ↑ Lithuania -Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. US Department of State, February 23, 2001. Accessed September 14, 2007.

- ↑ (in Polish) Tadeusz Andrzejewski, IX posiedzenie podzespołu ds. edukacji mniejszości narodowych w sprawach litewskiej oświaty na Sejneńszczyźnie, Tygodnik Wileńszczyzny, 23 - 29 marca 2006 r. nr 12

- ↑ (in Polish) 5 kadencja, 10 posiedzenie, 1 dzień (15.02.2006) 2 punkt porządku dziennego: Informacja Ministra Spraw Zagranicznych o zadaniach polskiej polityki zagranicznej w 2006 r.

- ↑ (in Polish) Posiedzenie Komisji w dniu 11 kwietnia 2007 roku, Komisja Spraw Emigracji i Łączności z Polakami za Granicą.

- ↑ RAXEN_CC National Focal Point Lithuania

- ↑ Memorandum to the Lithuanian Government Assessment of the progress made in implementing the 2004 recommendations of the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Council of Europe, 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "Lietuvos Respublikos Konstitucinis Teismas". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ Polish press review - Government & Economy. Wirtualna Polska, 10/08/2007

- ↑ "Litewski Sejm gra Kartą Polaka". Rzeczpospolita. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ (in Polish) Mickiewicz czy Mickevičius? WALKA O POLSKIE NAZWISKA NA LITWIE, TVN24, 22.10.2008

- ↑ (in Polish) Polak z Wilna walczy o polską pisownię swego nazwiska, Gazeta Wyborcza, 2005-07-25

- ↑ (in Polish) Michal Klečkovskis walczy o rodowe nazwisko Kleczkowski

- ↑ (in Polish) Kleczkowski czy Klečkovski?, Tygodnik Wileńszczyzny, no.31, 2005

- ↑ http://archive.is/20120802030529/http://www.efhr.eu/2012/04/26/the-european-parliament-considers-the-rights-of-the-polish-minority-in-lithuania-to-be-a-very-important-matter-below-is-mr-tomasz-snarskis-account-of-the-committee-on-petitions-mee/?lang=en. Archived from the original on August 2, 2012. Retrieved May 8, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Przecież jestem Snarski, a nie Snarskis" (in Polish). Wyborcza.pl. 2002-02-03. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ↑ Przedstawiciel rządu na powiat wileński narusza Konwencję Ramową RE

- ↑ "Strona nie została znaleziona — EUROPEJSKA FUNDACJA PRAW CZŁOWIEKA".

- ↑ "New Page 1". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Divine Painting". Archived from the original on 2006-10-06.

- ↑ "News". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ editor. "Seimas votes against original foreign surnames in passports again | The Lithuania TribuneThe Lithuania Tribune". Lithuaniatribune.com. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ↑ "Litewska prokuratura przesłuchuje weteranów AK". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved 2009-05-10.

Vilnija to organizacja skrajna, nacjonalistyczna, której głównym celem jest likwidacja skutków wielowiekowej dominacji Polski nad Litwą i tzw. okupacji Wileńszczyzny w międzywojniu.

- ↑ Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (September 2004). "Dr Garsva - prezes nacjonalistycznego stowarzyszenia Vilnija (...)". Media zagraniczne o Polsce (Foreign Media on Poland) (in Polish). XIII (2409 (3162)).

- ↑ "Uknuli prowokację". Tygodnik Wileńszczyzny (in Polish). November 2005. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ BNS. "Buvęs ambasadorius kritikuoja Lietuvos lenkų lyderius (Ex-ambassador criticizes leaders of Polish community)" (in Lithuanian). Delfi.lt. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ↑ "Wiadomości | wiadomości tv.rp.pl, informacje, ekonomia, prawo | rp.pl" (in Polish). Rzeczpospolita.pl. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- ↑ (in Polish) Polacy atakowani w mediach, rp.pl, 21-05-2008

- ↑ (in Polish) Litwa: Polacy zwracają się do władz o pomoc, interia.pl, 21-05-2008

- ↑ (in Polish) Związek Polaków na Litwie apeluje o zaprzestanie kampanii przeciwko mniejszościom narodowym, 21-05-2008

- ↑ "Liste complète".

- ↑ "Lithuania-Poland : School strike suspended, tensions remain".

- ↑ Statement by Knut Vollebaek, OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities

- ↑ "Kara powyżej 40 tys. litów za dwujęzyczne tabliczki". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Kolejna grzywna za tabliczki. Nie ma nowego "rekordu"...". Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ Some graduates' surnames from Władysław Syrokomla's name school, Vilnius

- ↑ "Kurier Wileński". Kurier Wileński. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑

- ↑

- 1 2 (in Polish) AKCJA WYBORCZA POLAKÓW NA LITWIE. Encyklopedia Interia. Last accessed 20 January 2007.

- ↑ "Kultūros ministerijoje pradėjo dirbti trečiasis viceministras".

- ↑ "Litewski rząd powołał wiceministra ds. mniejszości narodowych :: polityka". Kresy.pl. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polish minority in Lithuania. |

- POLES IN LITHUANIA FROM THE SECOND HALF OF 1944 UNTIL 1946: CHOOSING BETWEEN STAYING OR EMIGRATING TO POLAND by VITALIJA STRAVINSKIENĖ, The Lithuanian Institute of History, January 19, 2006

- Chronology for Poles in Lithuania

- The Polish language in education in Lithuania

- Discrimination in Lithuania

- Observance of Polish minority rights in Lithuania Report by «Wspólnota Polska», Union of Poles in Lithuania and the Association of Teachers of Polish Schools in Lithuania, 2009

- The Polish national minority in Lithuania : three reports later.

- (in Polish) Organizacje Polonii na Litwie (Organizations of Polonia in Lithuania)

- (in Polish) Polonia na świecie (Polonia worldwide) with section on Lithuania

- "Polacy na Litwie" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2005-04-03. (Poles in Lithuania)

- (in Polish) Losy ludności polskiej na Litwie (Fate of Polish population in Lithuania)

- (in Polish) Jan Sienkiewicz, Przestrzeganie praw polskiej grupy etnicznej w Republice Litewskiej (Respecting the righs of the Polish minority in Lithuania)

- (in Polish) Polacy na Litwie w prawie (Lithuanian law on minorities)

Bibliography

- Łossowski, Piotr; Bronius Makauskas (2005). Kraje bałtyckie w latach przełomu 1934-1944 (in Polish). Scientific Editor Andrzej Koryna. Warszawa: Instytut Historii PAN; Fundacja Pogranicze. ISBN 83-88909-42-8.

- Kupczak, Janusz M. (1998). "Z problematyki stosunków narodowościowych na Litwie współczesnej". Politologia. XXII.

- Zbigniew Kurcz, "Mniejszość polska na Wileńszczyźnie", Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, Wrocław 2005, ISSN 0239-6661, ISBN 83-229-2601-4.