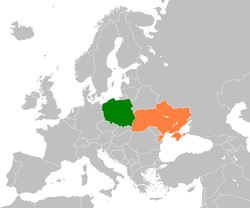

Poland–Ukraine relations

| |

Poland |

Ukraine |

|---|---|

Polish–Ukrainian relations as international relations were revived soon after Ukraine gained independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. They have been both improving and deteriorating since. Various controversies from their shared history occasionally resurface in Polish–Ukrainian relations, but they are not having a major influence on the bilateral relations of Poland and Ukraine.[1]

Ukraine and Poland are respectively, the second and third largest Slavic countries, after Russia. The two countries share a border of about 529 km.[2] Poland's acceptance of the Schengen Agreement created problems with the Ukrainian border traffic. On July 1, 2009, an agreement on local border traffic between the two countries came into effect, which enables Ukrainian citizens living in border regions to cross the Polish frontier according to a liberalized procedure.[3]

Ukraine is the country with the largest number of Polish consulates.[4]

History of relations

Polish-Ukrainian relations can be traced to the 16th-17th centuries in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the often turbulent relations between that state and the mostly polonized nobility (szlachta) and the Cossacks. And even further into the 13th-14th centuries when the Kingdom of Poland and the Ruthenian Kingdom carried close ties.

The next stage would be the relations in the years 1918–1920, in the aftermath of World War I, which saw both the Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Ukrainian alliance. The interwar period would eventually see independent Poland while the Ukrainians had no state of their own, being divided between Poland and the Soviet Union. This led to a deterioration of Polish-Ukrainian relations, and would result in a flare-up of ethnic tensions during and immediately after World War II (massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Operation Vistula being the most infamous).

While this left the Polish-Ukrainian relations in the mid-20th century in a relatively poor state, there was little meaningful and independent diplomacy and contact between the Polish People's Republic (Poland) and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (Ukraine). The situation changed significantly with the fall of communism, when both Poland and Ukraine became fully independent and could once again decide on foreign policies of their own.

Modern era

On October 13, 1990 Poland and Ukraine agreed to the "Declaration on the foundations and general directions in the development of Polish-Ukrainian relations". Article 3 of this declaration said that neither country has any territorial claims against the other, and will not bring any in the future. Both countries promised to respect the rights of national minorities on their territories and to improve the situation of minorities in their countries.

Support for Ukrainian sovereignty has become an important component of Polish foreign policy.[5] Poland strongly supported the peaceful and democratic resolution of the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine, and has backed NATO-Ukraine cooperation (such as the Lithuanian–Polish–Ukrainian Brigade), as well as Ukraine's efforts to join the European Union.[5][6]

Poland has been an avid supporter of Ukraine throughout the tumultuous period of the Euromaidan and the 2014 Crimean Crisis. The Polish government has campaigned for Ukraine in the European Union and is a supporter of sanctions against Russia for its actions in Ukraine. Poland has declared that they will never recognize the annexation of Crimea by Russia. In 2014, Poland's ex-foreign minister Radoslaw Sikorski alleged that in 2008, Russian President Vladimir Putin proposed to then Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk in the division of Ukraine between Poland and Russia. Sikorski later stated that some words had been over-interpreted, and that Poland do not take part in annexations. [7]

Nevertheless, historical issues regarding the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) and their massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia remain a contested topic today. In July 2016, the Polish Sejm passed a resolution, authored by the Law and Justice party, making July 11 a National Day of Remembrance of Victims of Genocide, noting that over 100,000 Polish citizens were massacred during an coordinated attack by the UPA. [8] Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko voiced regrets on the decision, arguing that it can led to "political speculation". In response, Ukrainian MP Oleksii Musii drafted a resolution declaring March 24 "Memorial Day of the Victims of Polish state genocide against Ukrainians in 1919-1951". The Marshal of the Polish Senate Stanislaw Karczewski condemned the motion. [9]

In 2016, a special screening of the Polish film Volhynia by the Polish Institute in Kiev for Ukrainian MPs was postponed due to concerns concerns that it may disrupt public order, on recommendations from the Ukrainian foreign ministry.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Copsey, 2006.

- ↑ "Informacje o Polsce - informacje ogólne" [Information about Poland - general information] (in Polish). prezydent.pl. 22 February 2005. Archived from the original on 2005-02-22.

- ↑ "Local Border Traffic Agreement With Poland Takes Effect". Ukrainian News Agency. 1 July 2009.

- ↑ "Poland to open consulate general in Sevastopol in 2010". Kyiv Post. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-05-18.

- 1 2 Zajączkowski, 2005.

- ↑ Polskie Radio. Poland supports Ukraine retrieved 18.03.2008

- ↑ "Polish ex-minister quoted saying Putin offered to divide Ukraine with Poland". Reuters. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ "Polish MPs adopt resolution calling 1940s massacre genocide". Radio Poland. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Marshal of Polish Senate Warns Ukraine against Adopting Resolution on Genocide". Ukrayinska Pravda. 4 August 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Kiev screening of Polish film on WWII massacre postponed". Radio Poland. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

Further reading

- R. and K. Wolczuk, Poland and Ukraine: a strategic partnership in a changing Europe? Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2003.

- Iffly, Catherine, Du conflit à la coopération? Les rapprochements franco-allemand, germano-polonais et polono-ukrainien en perspective comparée (The French-German, German-Polish and Polish-Ukrainian Rapprochements in Comparative Perspective), Revue d'Allemagne, 35/4, 2003.

- Zajączkowski, Wojciech, Polish-Ukrainian Relations, Yearbook of Polish Foreign Policy (01/2005),

- Siwiec, Marek, The Polish-Ukrainian Relations during the Last Decade, The Polish Foreign Affairs Digest (4 (5)/2002),

- Joanna Konieczna, Poles and Ukrainians, Poland and Ukraine: The Paradoxes of Neighbourly Relations

- Kevin Hannan, review of Polska-Ukraina: 1000 lat sąsiedztwa, The Sarmatian Review, September 2004

- Copsey, N. (2006) Echoes of the Past in Contemporary Politics: the case of Polish-Ukrainian Reconciliation, SEI Working Paper, No. 87.

- Oleksandr Pavliuk, The Ukrainian-Polish Strategic Partnership and Central European Geopolitics

- Litwin Henryk, Central European Superpower, BUM Magazine, 2016.

- Дрозд Р., Гальчак Б. Історія українців у Польщі в 1921–1989 роках / Роман Дрозд, Богдан Гальчак, Ірина Мусієнко; пер. з пол. І. Мусієнко. 3-тє вид., випр., допов. – Харків : Золоті сторінки, 2013. – 272 с.

- Roman Drozd, Roman Skeczkowski, Mykoła Zymomrya: Ukraina — Polska. Kultura, wartości, zmagania duchowe. Koszalin: 1999.

- Roman Drozd, Bohdan Halczak: Dzieje Ukraińców w Polsce w latach 1921–1989». Warszawa: 2010