Point Reyes National Seashore

| Point Reyes National Seashore | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

|

Headlands of the Point Reyes Peninsula from Chimney Rock, looking north. | |

| |

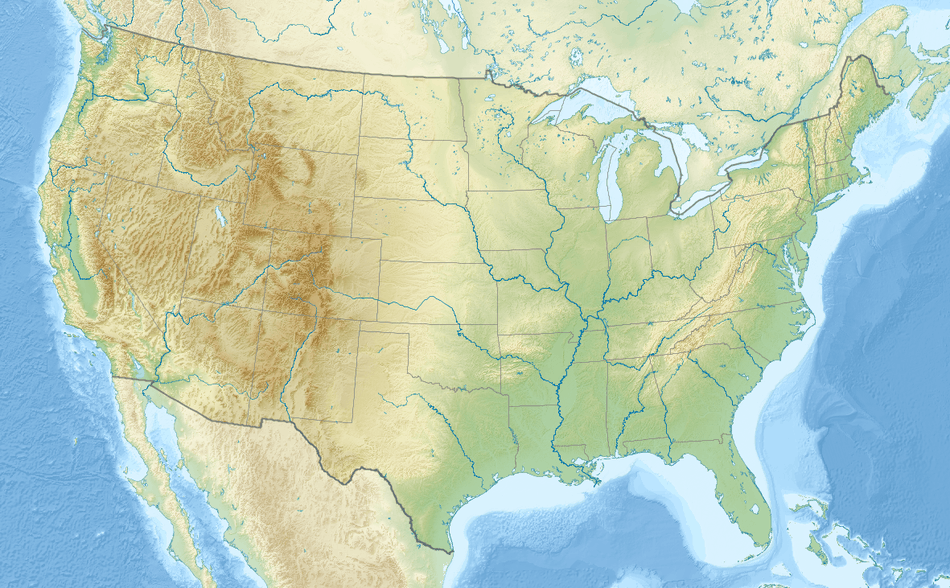

| Location | Marin County, California, United States |

| Nearest city | Point Reyes Station, California |

| Coordinates | 38°4′N 122°53′W / 38.067°N 122.883°WCoordinates: 38°4′N 122°53′W / 38.067°N 122.883°W[1] |

| Area | 71,028 acres (287.44 km2)[2] |

| Established | September 13, 1962 |

| Visitors | 2,412,663 (in 2012)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Point Reyes National Seashore |

Point Reyes National Seashore is a 71,028-acre (287.44 km2) park preserve located on the Point Reyes Peninsula in Marin County, California. As a national seashore, it is maintained by the US National Park Service as an important nature preserve. Some existing agricultural uses are allowed to continue within the park. Clem Miller, a US Congressman from Marin County wrote and introduced the bill for the establishment of Point Reyes National Seashore in 1962 to protect the peninsula from development which was proposed at the time for the slopes above Drake's Bay. All of the park's beaches were listed as the cleanest in the state in 2010.[4]

Description

The Point Reyes peninsula is a well defined area, geologically separated from the rest of Marin County and almost all of the continental United States by a rift zone of the San Andreas Fault,[5] about half of which is sunk below sea level and forms Tomales Bay. The fact that the peninsula is on a different tectonic plate than the east shore of Tomales Bay produces a difference in soils and therefore to some extent a noticeable difference in vegetation.

The small town of Point Reyes Station, although not actually located on the peninsula, nevertheless provides most services to it, though some services are also available at Inverness on the west shore of Tomales Bay. The even smaller town of Olema, about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Point Reyes Station, serves as the gateway to the Seashore and its visitor center, located on Bear Valley Road.

The peninsula includes wild coastal beaches and headlands, estuaries, and uplands. Although parts of the Seashore are commercially farmed, and parts are under the jurisdiction of other conservation authorities, the National Park Service provides signage and seeks to manage visitor impact on the entire peninsula and virtually all of Tomales Bay. The Seashore also administers the parts of the Golden Gate National Recreation area, such as the Olema Valley, that are adjacent to the Seashore.

The northernmost part of the peninsula is maintained as a reserve for Tule Elk, which are readily seen there.[6] The preserve is also very rich in raptors and shorebirds.[5]

The Point Reyes Lighthouse attracts whale-watchers looking for the Gray Whale migrating south in mid-January and north in mid-March.

The Point Reyes Lifeboat Station is a National Historic Landmark. It is the last remaining example of a rail launched lifeboat station that was common on the Pacific coast.

Nova Albion, Francis Drake's 1579 campsite; Sebastião Rodrigues Soromenho's 1595 wreck; and fifteen associated Native American sites are included in the Drakes Bay Historic and Archaeological District National Historic Landmark. This encompasses 5,965 acres along the coast of Drakes Bay.[7]

Kule Loklo, a recreated Coast Miwok village, is a short walk from the visitor center.

More than 30,000 acres (120 km2) of the Point Reyes National Seashore are designated as the Phillip Burton Wilderness, named in honor of California Congressman Phillip Burton, who wrote the legislation creating the Golden Gate National Recreation Area and was instrumental in helping to pass the California Wilderness Act of 1984.

The Point Reyes National Seashore attracts 2.5 million visitors annually. Hostelling International USA (part of Hostelling International) maintains a 45-bed youth hostel at the Seashore.[8]

Point Reyes National Seashore Association, formed in 1964, collaborates with the Seashore on maintenance, restoration and educational projects.[9]

Marine Protected Areas

Point Reyes State Marine Reserve & Point Reyes State Marine Conservation Area, Estero de Limantour State Marine Reserve & Drakes Estero State Marine Conservation Area and Duxbury Reef State Marine Conservation Area adjoin Point Reyes National Seashore. Like underwater parks, these marine protected areas help conserve ocean wildlife and marine ecosystems.

Drakes Estero oyster farm closure

A large shellfish farm raising Japanese (kumamoto) oysters, Crassostrea gigas, was located in Drakes Estero until, under court order, it closed down at end of 2014. Court appeals to keep the operation in place were dropped in December, 2014.[10]

The farm was purchased by the National Park Service in 1972, and the agency issued a permit to allow the previous owner to continue operations for 40 years. The business was sold to a new owner in 2004, the Drakes Bay Oyster Company, who was informed by the NPS at the time of purchase that their permit to operate would not be renewed beyond the November 30, 2012 expiration date.[11] A federal law enacted in 2009 authorized, but did not require, Interior Secretary Ken Salazar to renew the permit.[12] The NPS and conservation groups viewed the farm as an inappropriate and environmentally-insensitive use of the estero, which was designated a "potential wilderness area" by Congress. The farm's supporters argued that it was not ecologically harmful and was important to the local economy.[12][13]

On November 29, 2012, Salazar announced that he would not renew the permit, citing the original intent of the Point Reyes Wilderness Act to designate the area as wilderness upon the removal of the oyster farm.[11] Salazar visited the farm the previous week and later personally phoned the farm's owner to give him the news.[14]

The oyster farm closure was challenged in U.S. District Court on January 25, 2013.[15] The challenge was rejected by a federal court judge, who ruled that the law gave Salazar unfettered discretion to approve or deny a renewal of the permit.[16] The California Coastal Commission voted on February 7, 2013 to unanimously approve cease and desist and restoration orders for violations of the California Coastal Act.[17] The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rejected an appeal of the district court's decision, ruling on Sept. 3, 2013 that the oyster farm's owner had not shown a likelihood of success on the merits because Salazar had acted within his discretion in denying the permit.[18] An attempt to have the appeals court rehear the case was rejected on January 14, 2014 and a petition to the United States Supreme Court[19] was denied on June 30, 2014.[20] The oyster farm closed its on site retail operation on July 31, 2014.[21][22] However, controversy continues over the condition of the estero sea floor and the ongoing off shore operations.[23] Another lawsuit challenging the closure itself was rejected in September 2014.[24][25]

Hiking

Point Reyes has an excellent system of hiking trails for dayhiking and backpacking. Bear Valley Trail is the most popular hike in the park. Taking off from the visitor's center, it travels mostly streamside through a shaded, fern-laden canyon, breaking out at Divide Meadow before heading gently downward to the coast, where it emerges at the spectacular ocean view at Arch Rock. A portion of Arch Rock collapsed on 21 March 2015, killing one person.[26]

Three trails connecting from the west with the Bear Valley trail head upward toward Mt. Wittenberg, at 1,407 feet (429 m), the highest point in the park.[5]

Across the parking lot at the Visitor's Center is the Earthquake Trail which is a 0.6-mile (0.97 km) loop that runs directly over the San Andreas Fault, deep underground, so that it is possible to stand straddling the fault line. The trail provides descriptions of the fault and the surrounding geology, and there is a fence that was pulled 18 feet (5.5 m) apart during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[27]

At the western end of the Point Reyes Peninsula is the historic Point Reyes Lighthouse, reached by descending 308 steps. Unlike many lighthouses, that were built high so the light could be seen by ships far out to sea, the Point Reyes lighthouse was built low to get the light below the fog that is so prevalent in the area. Nearby is the short Chimney Rock hike, which is noted for its spring wildflower displays.[5]

As befitting a national seashore, Point Reyes offers several beach walks. Limantour Spit winds up on a narrow sandy beach, from which Drakes Beach can be glimpsed across Drakes Bay. North Beach and South Beach are often windswept and wave-pounded. Ocean vistas from higher ground can be seen from the Tomales Point Trail and, to the south, from the Palomarin trailhead at the park's southern entrance outside the town of Bolinas.

For backpackers, Point Reyes has four hike-in campgrounds available by reservation.

Point Reyes is a terminus of the American Discovery Trail which is the only transcontinental trail in the United States.[28]

Flora

Point Reyes lies within the California interior chaparral and woodlands ecoregion.

In his book The Natural History of the Point Reyes Peninsula, Jules Evens identifies several plant communities. One of the most prominent is the Coastal Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) forest, which includes Coast live oak, Tanoak, and California bay and reaches across the southern half of Inverness Ridge toward Bolinas Lagoon. Unlogged parts of this Douglas-fir forest contain trees over 300 years old and up to 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter. But despite these large, old trees, the forest may nevertheless be a result of European settlement. The Coast Miwok people who once lived in the area set frequent fires to clear brush and increase game animal populations, and early explorers' accounts describe the hills as bare and grassy. But as the Native American settlements were replaced by European ones from the seventeenth century onward, the forests expanded as fire frequency decreased, resulting in the forests we see today.[29]

The Bishop pine (Pinus muricata) forest is found on slopes in the northern half of the park. Many of these trees growing in thick swaths came from seeds released after the 1995 Mt. Vision fire.

Salt, brackish, and freshwater marshlands are found adjacent to Drakes Estero and Abbotts Lagoon. The other communities identified by Evens are the coastal strand, dominated by European beach grass (Ammophila arenaria), ice plant (Carprobrotus edulis, also called sea fig or Hottentot fig), sea rocket (Cakile maritima) and other species that thrive on the immediate coast; northern coastal prairie, found on a narrow strip just inland from the coastal strand that includes some native grasses; coastal rangeland, the area still grazed by the cattle from the peninsula's remaining working ranches;[30] northern coastal scrub, dominated by coyote bush (Baccharis pilularis); and the intertidal and subtidal plant communities.

Point Reyes is home to the only known population of the endangered Sonoma spineflower, Chorizanthe valida.[31]

Gallery

Point Reyes Beach from the Lighthouse Visitor Center

Point Reyes Beach from the Lighthouse Visitor Center McClure's Beach

McClure's Beach.jpg) Point Reyes Lighthouse

Point Reyes Lighthouse- Tomales Bay on the Eastern side

Coastline as seen from Chimney Rock

Coastline as seen from Chimney Rock

References

- ↑ "Point Reyes National Seashore". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2010". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- ↑ Bay Area beaches grade well for safe swimming, May 27, 2010 by Carolyn Jones, San Francisco Chronicle

- 1 2 3 4 Point Reyes National Seashore, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

- ↑ Post, Charles (March 19, 2015). "A Brief History of Tule Elk on the Point Reyes Peninsula". Marin Coast Guide.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Program: National Park Service: Drakes Bay Historic and Archeological District" (PDF). Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ↑ Archived June 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About Point Reyes National Seashore Association". Point Reyes National Seashore Association. Retrieved 2015-08-09.

- ↑ http://www.marinij.com/marinnews/ci_27061022/legal-stand-ends-drakes-bay-oyster-co-supporters

- 1 2 Secretary Salazar Issues Decision on Point Reyes National Seashore Permit, United States Department of the Interior, November 29, 2012

- 1 2 9th Circuit Mulls Fate of California Oyster Farm, Courthouse News Service, May 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Oyster farm battle". Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ↑ "Interior secretary denies renewal of oyster company lease on national seashore in California". Archived from the original on December 12, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Drakes Bay attorneys argue for injunction to keep oyster operation open". Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ↑ "Federal judge declines to halt closure of Drakes Bay Oyster Co.". Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ↑ Prado, Mark (February 8, 2013). "Point Reyes oyster farm dealt another setback". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ Appeals court deals blow to Drakes Bay Oyster Co., Bob Egelko, San Francisco Chronicle, Sept. 3, 2013

- ↑ "Court denies Drakes Bay Oyster Co. petition to have its case reheard". Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Supreme Court refuses to take Drakes Bay Case". Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ↑ Drakes Bay Oyster Co. to shut down this month per federal order, Mark Prado, Marin Independent Journal, July 10, 2014

- ↑ Cart, Julie (July 18, 2013). "Oyster farm must comply with California coastal laws, judge rules July 18, 2013". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.kcet.org/news/redefine/rewild/aquatic/trash-invasive-species-left-behind-as-controversial-oyster-farm-closes.html

- ↑ http://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/local/2676740-181/court-battle-over-drakes-bay

- ↑ Kovner, Guy. Judge rejects firms’ bid to keep Drakes Bay Oyster Co. open, Santa Rosa Press-Democrat, 9 September 2014

- ↑ "Hiker dies, another injured after cliff collapse in Point Reyes". SFGATE. March 22, 2015.

- ↑ Trail Guide & Suggested Hikes - Point Reyes National Seashore. Nps.gov. Retrieved on 2013-07-21.

- ↑ http://www.discoverytrail.org/ American Discovery Trail website retrieved October 21, 2010

- ↑ Brown, Peter M.; Kaye, Margot W.; Buckley, Dan (1999). "Fire History in Douglas-fir and Coast Redwood Forests at Point Reyes National Seashore, California" (PDF). Northwest Science. 73 (3): 205–216.

- ↑ Serna, Joseph (July 13, 2017). "Conservationists, National Park Service and Point Reyes ranchers reach settlement on disputed land". LA Times. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ↑ CNPS Profile: Chorizanthe valida

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Point Reyes National Seashore. |

- National Park Service official website about Point Reyes

-

Point Reyes National Seashore travel guide from Wikivoyage

Point Reyes National Seashore travel guide from Wikivoyage - West Marin Chamber of Commerce site about Point Reyes

- Point Reyes National Seashore Association, a nonprofit organization working in coordination with the National Park Service.

- Kule Loklo, a recreation of a Coast Miwok Indian village