Ring system

A ring system is a disc or ring orbiting an astronomical object that is composed of solid material such as dust and moonlets, and is a common component of satellite systems around giant planets. A ring system around a planet is also known as a planetary ring system.

The most prominent planetary rings in the Solar System are those around Saturn, but the other three giant planets (Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune) also have ring systems. Recent evidence suggests that ring systems may also be found around other types of astronomical objects, including minor planets, moons, and brown dwarfs.

Ring systems of planets

There are three ways that thicker planetary rings (the rings around planets) have been proposed to have formed: from material of the protoplanetary disk that was within the Roche limit of the planet and thus could not coalesce to form moons; from the debris of a moon that was disrupted by a large impact; or from the debris of a moon that was disrupted by tidal stresses when it passed within the planet's Roche limit. Most rings were thought to be unstable and to dissipate over the course of tens or hundreds of millions of years, but it now appears that Saturn's rings might be quite old, dating to the early days of the Solar System.[1]

Fainter planetary rings can form as a result of meteoroid impacts with moons orbiting around the planet or, in case of Saturn's E-ring, the ejecta of cryovolcanic material.[2][3]

The composition of ring particles varies; they may be silicate or icy dust. Larger rocks and boulders may also be present, and in 2007 tidal effects from eight 'moonlets' only a few hundred meters across were detected within Saturn's rings. The maximum size of a ring particle is determined by the specific strength of the material it is made of, its density, and the tidal force at its altitude. The tidal force is proportional to the average density inside the radius of the ring, or to the mass of the planet divided by the radius of the ring cubed. It is also inversely proportional to the square of the orbital period of the ring.

Sometimes rings will have "shepherd" moons, small moons that orbit near the inner or outer edges of rings or within gaps in the rings. The gravity of shepherd moons serves to maintain a sharply defined edge to the ring; material that drifts closer to the shepherd moon's orbit is either deflected back into the body of the ring, ejected from the system, or accreted onto the moon itself.

Jupiter

Jupiter's ring system was the third to be discovered, when it was first observed by the Voyager 1 probe in 1979,[4] and was observed more thoroughly by the Galileo orbiter in the 1990s.[5] Its four main parts are a faint thick torus known as the "halo"; a thin, relatively bright main ring; and two wide, faint "gossamer rings".[6] The system consists mostly of dust.[4][7]

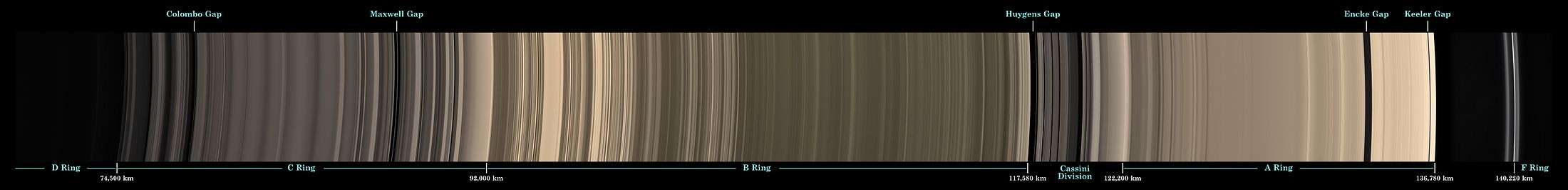

Saturn

Saturn's rings are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the solar system, and thus have been known to exist for quite some time. Galileo Galilei first observed them in 1610, but they were not accurately described as a disk around Saturn until Christiaan Huygens did so in 1655.[8] With help from the NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini mission, a further understanding of the ring formation and active movement was understood.[9] The rings are not a series of tiny ringlets as many think, but are more of a disk with varying density.[10] They consist mostly of water ice and trace amounts of rock, and the particles range in size from micrometers to meters.[11]

Uranus

Uranus' ring system lies between the level of complexity of Saturn's vast system and the simpler systems around Jupiter and Neptune. They were discovered in 1977 by James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink.[12] In the time between then and 2005, observations by Voyager 2[13] and the Hubble Space Telescope[14] led to a total of 13 distinct rings being identified, most of which are opaque and only a few kilometers wide. They are dark and likely consist of water ice and some radiation-processed organics. The relative lack of dust is due to aerodynamic drag from the extended exosphere-corona of Uranus.

Neptune

The system around Neptune consists of five principal rings that, at their densest, are comparable to the low-density regions of Saturn's rings. However, they are faint and dusty, much more similar in structure to those of Jupiter. The very dark material that makes up the rings are likely organics processed by radiation, like in the rings of Uranus.[15] 20 to 70 percent of the rings are dust, a relatively high proportion.[15] Hints of the rings were seen for decades prior to their conclusive discovery by Voyager 2 in 1989.

Rings systems of minor planets and moons

Reports in March 2008[16][17][18] suggested that Saturn's moon Rhea may have its own tenuous ring system, which would make it the only moon known to have a ring system. A later study published in 2010 revealed that imaging of Rhea by the Cassini spacecraft was inconsistent with the predicted properties of the rings, suggesting that some other mechanism is responsible for the magnetic effects that had led to the ring hypothesis.[19]

One minor planet is known to have rings, the centaur 10199 Chariklo. It has two rings, perhaps due to a collision that caused a chain of debris to orbit it. The rings were discovered when astronomers observed Chariklo passing in front of the star UCAC4 248-108672 on June 3, 2013 from seven locations in South America. While watching, they saw two dips in the star's apparent brightness just before and after the occultation. Because this event was observed at multiple locations, the conclusion that the dip in brightness was in fact due to rings is unanimously the leading theory. The observations revealed what is likely a 19-kilometer (12-mile)-wide ring system that is about 1,000 times closer than the Moon is to Earth. In addition, astronomers suspect there could be a moon orbiting amidst the ring debris. If these rings are the leftovers of a collision as astronomers suspect, this would give fodder to the idea that moons (such as the Moon) form through collisions of smaller bits of material. Chariklo's rings have not been officially named, but the discoverers have nicknamed them Oiapoque and Chuí, after two rivers near the northern and southern ends of Brazil.[20]

A second centaur, 2060 Chiron, is also suspected to have a pair of rings.[21][22] Based on stellar-occultation data that were initially interpreted as resulting from jets associated with Chiron's comet-like activity, the rings are proposed to be 324 (± 10) km in radius. Their changing appearance at different viewing angles can explain the long-term variation in Chiron's brightness over time.[22]

Ring systems may form around centaurs when they are tidally disrupted in a close encounter (within 0.4 to 0.8 times the Roche limit) with a giant planet. (By definition, a centaur is a minor planet whose orbit crosses the orbit(s) of one or more giant planets.) For a differentiated body approaching a giant planet at an initial relative velocity of 3−6 km/s with an initial rotational period of 8 hours, a ring mass of 0.1−10% of the centaur's mass is predicted. Ring formation from an undifferentiated body is less likely. The rings would be composed mostly or entirely of material from the parent body's icy mantle. After forming, the ring would spread laterally, leading to satellite formation from whatever portion of it spreads beyond the centaur's Roche Limit. Satellites could also form directly from the disrupted icy mantle. This formation mechanism predicts that roughly 10% of centaurs will have experienced potentially ring-forming encounters with giant planets.[23]

It had previously been theorized by some astronomers that Pluto might have a ring system.[24] However, this possibility has been ruled out by New Horizons, which would have detected any such ring system.

It is also predicted that Phobos, a moon of Mars, will break up and form into a planetary ring in about 50 million years, because its low orbit with an orbital period that is shorter than a Martian day is decaying due to tidal deceleration.[25][26]

Rings around exoplanets

Because all giant planets of the Solar System have rings, the existence of exoplanets with rings is plausible. Although particles of ice, the material that is predominant in the rings of Saturn, can only exist around planets beyond the frost line, within this line rings consisting of rocky material can be stable in the long term.[27] Such ring systems can be detected for planets observed by the transit method by additional reduction of the light of the central star if their opacity is sufficient. As of January 2015, no such observations are known.

A sequence of occultations of the star 1SWASP J140747.93-394542.6 observed in 2007 over 56 days was interpreted as a transit of a ring system of a (not directly observed) substellar companion dubbed “J1407b”.[28] This ring system is attributed a radius of about 90 million km (about 200 times that of Saturn's rings). In press releases, the term super-Saturn was dubbed.[29] However, the age of this stellar system is only about 16 million years, which suggests that this structure, if real, is more like a protoplanetary disk rather than a stable ring system in an evolved planetary system.

Visual comparison

References

- ↑ "Saturn's Rings May Be Old Timers". NASA (News Release 2007-149). December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ Spahn, F.; et al. (2006). "Cassini Dust Measurements at Enceladus and Implications for the Origin of the E Ring". Science. 311 (5766): 1416–8. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1416S. PMID 16527969. doi:10.1126/science.1121375.

- ↑ Porco, C. C.; Helfenstein, P.; Thomas, P. C.; Ingersoll, A. P.; Wisdom, J.; West, R.; Neukum, G.; Denk, T.; Wagner, R. (10 March 2006). "Cassini Observes the Active South Pole of Enceladus". Science. 311 (5766): 1393–1401. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1393P. PMID 16527964. doi:10.1126/science.1123013.

- 1 2 Smith, Bradford A.; Soderblom, Laurence A.; Johnson, Torrence V.; Ingersoll, Andrew P.; Collins, Stewart A.; Shoemaker, Eugene M.; Hunt, G. E.; Masursky, Harold; Carr, Michael H. (1979-06-01). "The Jupiter System Through the Eyes of Voyager 1". Science. 204 (4396): 951–972. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17800430. doi:10.1126/science.204.4396.951.

- ↑ Ockert-Bell, Maureen E.; Burns, Joseph A.; Daubar, Ingrid J.; Thomas, Peter C.; Veverka, Joseph; Belton, M. J. S.; Klaasen, Kenneth P. (1999-04-01). "The Structure of Jupiter's Ring System as Revealed by the Galileo Imaging Experiment". Icarus. 138 (2): 188–213. Bibcode:1999Icar..138..188O. doi:10.1006/icar.1998.6072.

- ↑ Esposito, Larry W. (2002-01-01). "Planetary rings". Reports on Progress in Physics. 65 (12): 1741. ISSN 0034-4885. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/65/12/201.

- ↑ Showalter, Mark R.; Burns, Joseph A.; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N.; Pollack, James B. (1987-03-01). "Jupiter's ring system: New results on structure and particle properties". Icarus. 69 (3): 458–498. Bibcode:1987Icar...69..458S. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90018-2.

- ↑ "Historical Background of Saturn's Rings". www.solarviews.com. Retrieved 2016-06-15.

- ↑ "Cassini - In Depth | Missions - NASA Solar System Exploration". NASA Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ Tiscareno, Matthew S. (2013-01-01). Oswalt, Terry D.; French, Linda M.; Kalas, Paul, eds. Planetary Rings. Springer Netherlands. pp. 309–375. ISBN 9789400756052. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5606-9_7.

- ↑ Porco, Carolyn. "Questions about Saturn's rings". CICLOPS web site. Retrieved 2012-10-05.

- ↑ Elliot, J. L.; Dunham, E.; Mink, D. (1977-05-26). "The rings of Uranus". Nature. 267 (5609): 328–330. doi:10.1038/267328a0.

- ↑ Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Beebe, R.; Bliss, D.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A.; Briggs, G. A.; Brown, R. H.; Collins, S. A. (1986-07-04). "Voyager 2 in the Uranian System: Imaging Science Results". Science. 233 (4759): 43–64. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17812889. doi:10.1126/science.233.4759.43.

- ↑ Showalter, Mark R.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2006-02-17). "The Second Ring-Moon System of Uranus: Discovery and Dynamics". Science. 311 (5763): 973–977. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16373533. doi:10.1126/science.1122882.

- 1 2 Smith, B. A.; Soderblom, L. A.; Banfield, D.; Barnet, C; Basilevsky, A. T.; Beebe, R. F.; Bollinger, K.; Boyce, J. M.; Brahic, A. (1989-12-15). "Voyager 2 at Neptune: Imaging Science Results". Science. 246 (4936): 1422–1449. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17755997. doi:10.1126/science.246.4936.1422.

- ↑ http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/cassini/media/rhea20080306.html NASA – Saturn's Moon Rhea Also May Have Rings

- ↑ Jones, G. H.; et al. (2008-03-07). "The Dust Halo of Saturn's Largest Icy Moon, Rhea". Science. 319 (5868): 1380–1384. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1380J. PMID 18323452. doi:10.1126/science.1151524.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. (2008-03-06). "A Ringed Moon of Saturn? Cassini Discovers Possible Rings at Rhea". The Planetary Society web site. Planetary Society. Retrieved 2008-03-09. External link in

|work=(help) - ↑ Tiscareno, Matthew S.; Burns, Joseph A.; Cuzzi, Jeffrey N.; Hedman, Matthew M. (2010). "Cassini imaging search rules out rings around Rhea". Geophysical Research Letters. 37 (14): L14205. Bibcode:2010GeoRL..3714205T. arXiv:1008.1764

. doi:10.1029/2010GL043663.

. doi:10.1029/2010GL043663. - ↑ "Surprise! Asteroid Hosts A Two-Ring Circus Above Its Surface". Universe Today. March 2014.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, E. (2015-01-27). "A second ringed centaur? Centaurs with rings could be common". Planetary Society. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- 1 2 Ortiz, J.L.; Duffard, R.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Alvarez-Candal, A.; Santos-Sanz, P.; Morales, N.; Fernández-Valenzuela, E.; Licandro, J.; Campo Bagatin, A.; Thirouin, A. (2015). "Possible ring material around centaur (2060) Chiron". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 576: A18. Bibcode:2015yCat..35760018O. arXiv:1501.05911

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424461.

. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201424461. - ↑ Hyodo, R.; Charnoz, S.; Genda, H.; Ohtsuki, K. (2016-08-29). "Formation of Centaurs’ Rings Through Their Partial Tidal Disruption During Planetary Encounters". The Astrophysical Journal. 828 (1): L8. arXiv:1608.03509

. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/828/1/L8.

. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/828/1/L8. - ↑ Steffl, Andrew J.; Stern, S. Alan (2007). "First Constraints on Rings in the Pluto System". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (4): 1485–1489. Bibcode:2007AJ....133.1485S. arXiv:astro-ph/0608036

. doi:10.1086/511770.

. doi:10.1086/511770.

- ↑ Holsapple, K. A. (December 2001). "Equilibrium Configurations of Solid Cohesionless Bodies". Icarus. 154 (2): 432–448. Bibcode:2001Icar..154..432H. doi:10.1006/icar.2001.6683.

- ↑ Gürtler, J. & Dorschner, J: "Das Sonnensystem", Barth (1993), ISBN 3-335-00281-4

- ↑ Hilke E. Schlichting, Philip Chang (2011). "Warm Saturns: On the Nature of Rings around Extrasolar Planets that Reside Inside the Ice Line". Astrophysical Journal. 734 (2): 117. Bibcode:2011ApJ...734..117S. arXiv:1104.3863

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/734/2/117.

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/734/2/117. - ↑ Matthew A. Kenworthy, Eric E. Mamajek (2015). "Modeling giant extrasolar ring systems in eclipse and the case of J1407b: sculpting by exomoons?". The Astrophysical Journal. 800 (2): 126. Bibcode:2015ApJ...800..126K. arXiv:1501.05652

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/800/2/126.

. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/800/2/126. - ↑ Rachel Feltman (2015-01-26). "This planet's rings make Saturn look puny". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Planetary rings. |

- USGS/IAU Ring and Ring Gap Nomenclature

- Everything a Curious Mind Should Know About Planetary Ring Systems with Dr Mark Showalter, Bridging the Gaps: A Portal for Curious Minds

.jpg)