Pinckney's Treaty

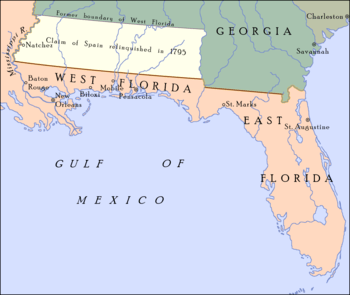

Pinckney's Treaty, also commonly known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed in San Lorenzo de El Escorial on October 27, 1795 and established intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain. It also defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi River. With this agreement, the first phase of the on-going border dispute between the two nations in this region, commonly called the West Florida Controversy, came to a close.[1]

The treaty's full title is Treaty of Friendship, Limits, and Navigation Between Spain and the United States. Thomas Pinckney negotiated the treaty for the United States and Don Manuel de Godoy represented Spain. It was presented to the United States Senate on February 26, 1796, and, after debate, was ratified on March 7, 1796. It was ratified by Spain on April 25, 1796 and ratifications were exchanged on that date. The treaty was proclaimed on August 3, 1796.

Background

In 1763, Great Britain established two colonies—East Florida and West Florida—out of territory along the northern Gulf of Mexico coast taken from France and Spain following the French and Indian War(the Seven Years' War). From Spain the British received all of Spanish Florida, and from France received the portion of French Louisiana east of the Mississippi River – New Orleans plus all of French Louisiana west of the Mississippi had been secretly given to Spain the previous year. Both East and West Florida, never extensively colonized by the British, were ceded to Spain (who subsequently ruled both provinces as separate and apart from Louisiana) in the 1783 Treaty of Paris at the end of the American Revolutionary War. When this transaction was made however, the boundaries of West Florida, which had changed while under British sovereignty, were not specified.

In 1763 West Florida's northern border was initially set at the 31st parallel north, but was moved in 1764 to 32° 22′ (the junction of the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers, and location of present day Vicksburg, Mississippi) in order to give the West Floridians more territory, including the Natchez District and the Tombigbee District. After reacquiring the colony, Spain insisted that its West Florida claim extended fully to 32° 22′, but the U.S. asserted that the land between 31° and 32° 22′ had always been British territory, and therefore rightfully belonged to the United States.

In 1784, the Spanish closed New Orleans to American goods coming down the Mississippi River. In 1795, the border was settled, and the US and Spain concluded a trade agreement. New Orleans was reopened, and Americans could transfer goods without paying cargo fees (right of deposit) when they transferred goods from one ship to another.[2]

Key treaty terms

Article II

Established the southern boundary of the United States with the Spanish colonies of East Florida and West Florida as: a line beginning on the River Mississippi at the 31st parallel north (the 1763 line) drawn due east to the middle of the Chattahoochee River and, from there, downstream along the middle of the river to the junction with the Flint River and, from there, due east to the headwaters of the St. Marys River and, from there, along the middle of the channel to the Atlantic Ocean.[3]

Article III

Stipulated that a joint Spanish-American team would survey the boundary line.[3]

Article IV

Established the western boundary of the United States with the Spanish colony of Louisiana, as: the middle of the Mississippi River from the northern boundary of the United States (it was unknown at the time how far north the Mississippi extended) to the 31st degree north latitude; and that both Spanish subjects and U.S. citizens would have free navigation along the full length of the Mississippi, from its source to the Ocean.[3]

Article V

The United States and Spain agreed not to incite native tribes to warfare and to promote mutually beneficial trade relationships the tribe on both sides of the border.[3] Previously, Spain had been supplying weapons to local tribes for many years. The agreement put the lands of the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations of American Indians within the new boundaries of the United States.[4]

Articles VI and VII

Spain and the United States also agreed to protect and defend the vessels of the other party anywhere within their jurisdictions and not to detain or embargo the other's citizens or vessels.[3]

Ramifications

The region that Spain relinquished its claim to through Pinckney's treaty was organized by Congress as Mississippi Territory on April 7, 1798. Natchez was the territory's first and only capital.

Grant (1997) argues that the treaty was critical for the emergence of American expansionism (later known as "Manifest Destiny") because control of the Natchez and Tombigbee districts were needed for America's dominance of the Southwest. The collapse of Spanish power in the region was inevitable as Americans poured into the district, and very few Spaniards lived there. Spain gave up the area for reasons of international politics, not local unrest. Spanish rule was accepted by the French and British settlers near Natchez. Relations with the Indians were tranquil. However, with the loss of Natchez, Spain's frontier was no longer secure, and the rest of its territory was lost piecemeal.[5]

Under the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso of October 1, 1800, Spanish Louisiana—comprising both the vast territory west of the Mississippi and New Orleans—was formally retroceded to France; but Spain continued to administer it. Again, as in 1783, the boundaries of the territory being exchanged were not specified. As a result, when France and the United States concluded the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, a new dispute arose, the second phase of the West Florida Controversy.

This time, the disagreement was over whether the portion of West Florida first under British and then Spanish control since 1763 (between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers) was included in the 1801 treaty, and thus the Louisiana Purchase. The United States laid claim to the region, asserting it was. Spain held that such a claim was baseless.[6][7][8][9] The dispute led American and British settlers in the region to declare an independent Republic of West Florida in 1810. The Republic was quickly annexed by the U.S., and incorporated into the Territory of Orleans, which joined the Union as the state of Louisiana in 1812.

Also in 1812, the United States annexed the Mobile District of West Florids, between the Perdido and Pearl Rivers, declaring that it had been included in the Louisiana Purchase.[10] Spain disputed this and maintained its claim over the area. The following year, a Federal statute was secretly enacted authorizing the President to take full possession of this area with the use of military force ("and naval force") as deemed necessary.[11] Accordingly, General James Wilkinson occupied this district with a military contingent; the Spanish colonial commandant offered no resistance. The annexed land was incorporated into the Mississippi Territory. In 1819 the U.S. and Spain negotiated the Adams–Onís Treaty, in which Spain ceded both West Florida and East Florida in their entirety to the United States.

Andrew Ellicott served as the head of the U.S. contingent. Since the mid–19th century, the southern east-west boundary established by Pinckney's Treaty has formed the state line between:

- Florida and Georgia

- Florida and Alabama – between the Chattahoochee and Pearl Rivers

- Louisiana and Mississippi – between the Perdido River and the Mississippi

The line is not a state line between the Pearl and Perdido Rivers so as to provide Mississippi and Alabama with access to the Gulf of Mexico.

See also

- History of Alabama

- History of Florida

- History of Louisiana

- History of Mississippi

- List of United States treaties

- Spanish-American relations

References

- ↑ Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1960) [1926]. Pinckney's Treaty: A Study of America's Advantage from Europe's Distress, 1783–1800 (2nd ed.).

- ↑ Gerard H. Clarfield,"Victory in the West: A Study of the Role of Timothy Pickering in the Successful Consummation of Pinckney's Treaty." Essex Institute Historical Collections 101.4 (1965): 333+.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Pinckney's Treaty". Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ↑ O'Brien, Greg (2005) [2002]. "Choctaw and Power". Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750–1830. University of Nebraska Press.

- ↑ Grant, Ethan (Spring 1997). "The Treaty of San Lorenzo and Manifest Destiny" (PDF). Gulf Coast Historical Review. Mobile, Alabama: History Dept. of the University of South Alabama. 12 (2): 44–57. ISSN 0892-9025 – via Tuskegee University Archives (2017).

- ↑ Raymond A. Young,"Pinckney's Treaty - A New Perspective," Hispanic American Historical Review, November 1963, Vol. 43 Issue 4, pp 526–539

- ↑ Chambers, Henry E. (May 1898). "West Florida and its relation to the historical cartography of the United States" (PDF). Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- ↑ Cox, Isaac Joslin (1918). The West Florida Controversy, 1798-1813 – a Study in American Diplomacy. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins Press.

- ↑ Curry, J. L. M. (April 1888). "The Acquisition of Florida". Magazine of American History. XIX: 286–301.

- ↑ "An Act to enlarge the boundaries of the Mississippi territory"

- ↑ "An Act authorizing the President of the United States to take possession of a tract of country lying south of the Mississippi territory and west of the river Perdido"

Further reading

- Young, Raymond A. "Pinckney's Treaty - A New Perspective," Hispanic American Historical Review, Nov 1963, Vol. 43 Issue 4, pp 526–539

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Treaty of San Lorenzo/ Pinckney’s Treaty, 1795 Milestones: 1784–1800; Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, United States Department of State, Washington, D.C.

- Treaty of Friendship, Limits, and Navigation Between Spain and The United States; October 27, 1795 Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School, New Haven, Connecticut

.jpg)