Presidency of Franklin Pierce

The presidency of Franklin Pierce began on March 4, 1853, when Franklin Pierce was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1857. Pierce, a Democrat from New Hampshire, took office as the 14th United States president after routing Whig Party nominee Winfield Scott in the 1852 presidential election. Seen by fellow Democrats as pleasant and accommodating to all the party's factions, Pierce, then a little-known politician, won the presidential nomination on the 49th ballot of the 1852 Democratic National Convention.

As president, Pierce oversaw a series of executive branch departmental reforms that improved accountability. He simultaneously attempted to enforce neutral standards for civil service while also satisfying the diverse elements of the Democratic Party with patronage, an effort which largely failed and turned many in his party against him. He also vetoed funding for internal improvements and called for a lower tariff. Sympathetic to the Young America expansionist movement, Pierce supported the Gadsden land purchase from Mexico and led a failed attempt to acquire Cuba from Spain. Pierce's administration was severely criticized over this when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto, calling for the annexation of Cuba by force if necessary.

His popularity in the Northern "free" states declined sharply after he supported the 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act, which nullified the Missouri Compromise; though many whites in the South continued to support him. Passage of the act led directly to a long and violent conflict over the expansion of slavery in the American West. In its wake the Whig Party was destroyed, and the Democratic Party was severely weakened, while a new and strictly northern political force, the Republican Party emerged.

Although Pierce actively sought renomination at the 1856 Democratic National Convention, he was defeated by James Buchanan, who went on to win the 1856 presidential election. Pierce is viewed by presidential historians as an inept chief executive, whose failure to stem the nation's inter–sectional conflict accelerated the course towards civil war. He is generally ranked as one of the worst presidents of all time.

Election of 1852

As the 1852 presidential election approached, the Democrats were divided by the slavery issue, though most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party in 1848 with Martin Van Buren had returned. It was widely expected that the 1852 Democratic National Convention would result in deadlock, with no major candidate able to win the necessary two-thirds majority. New Hampshire Democrats felt that, as the state in which their party had most consistently gained Democratic majorities, they should supply the presidential candidate. Other possible standard-bearers included Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Lewis Cass of Michigan, William Marcy of New York, Sam Houston of Texas, and Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.[1] Pierce quietly allowed his supporters to lobby for him, with the understanding that his name would not be entered at the convention unless it was clear none of the front-runners could win. To broaden his potential base of southern support as the convention approached, he wrote letters reiterating his support for the Compromise of 1850, including the controversial Fugitive Slave Act.[2]

The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, Maryland, and the deadlock occurred as expected. The first ballot was taken on June 3. Of 288 delegates, Cass claimed 116, Buchanan 93, and the rest were scattered, without a single vote for Pierce. The next 34 ballots passed with no-one near victory, and still no votes for Pierce. The Buchanan team decided to have their delegates vote for minor candidates, including Pierce, to demonstrate that no one but Buchanan could win. It was hoped that once delegates realized this, the convention would unite behind Buchanan. This novel tactic backfired after several ballots as Virginia, New Hampshire, and Maine switched to Pierce; the remaining Buchanan forces began to break for Marcy, and before long Pierce was in third place. After the 48th ballot, North Carolina Congressman James C. Dobbin delivered an unexpected and passionate endorsement of Pierce, sparking a wave of support for the dark horse candidate. On the 49th ballot, Pierce received all but six of the votes, and thus gained the Democratic nomination for president. Delegates selected Alabama Senator William R. King, a Buchanan supporter, as Pierce's running mate, and adopted a party platform that rejected further "agitation" over the slavery issue and supported the Compromise of 1850.[3]

Rejecting incumbent President Millard Fillmore, the Whigs nominated General Winfield Scott, whom Pierce had served under in Mexico. The Whigs could not unify their factions as the Democrats had, and the convention adopted a platform almost indistinguishable from that of the Democrats, including support of the Compromise of 1850. This incited the Free Soilers to field their own candidate, Senator Hale of New Hampshire, at the expense of the Whigs. The lack of political differences reduced the campaign to a bitter personality contest and helped to dampen voter turnout in the election to its lowest level since 1836; it was, according to Pierce biographer Peter A. Wallner, "one of the least exciting campaigns in presidential history".[4] Scott was harmed by the lack of enthusiasm of anti-slavery northern Whigs for the candidate and platform; New-York Tribune editor Horace Greeley summed up the attitude of many when he said of the Whig platform, "we defy it, execrate it, spit upon it".[5]

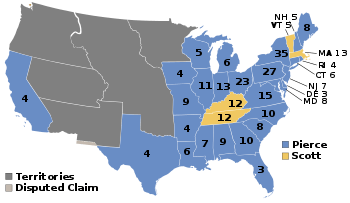

Pierce kept quiet so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign. It was the custom at the time for candidates to not appear to seek the office, and he did no personal campaigning.[6] Pierce's opponents caricatured him as an anti-Catholic coward and alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle").[7] Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by their pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker.[8] The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will pierce their enemies in 1852 as they poked [that is, Polked] them in 1844."[9] This proved to be true, as Scott won only Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote with 50.9 to 44.1 percent. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for Pierce's in-state rival, Hale, who won 4.9 percent of the popular vote.[10] In the concurrent Congressional elections, the Democrats increased their majorities in both houses of Congress.[11]

Tragedy and transition

BEP-engraved portrait of Pierce as president

Pierce began his presidency in mourning. Weeks after his election, on January 6, 1853, the President-elect's family had been traveling from Boston by train when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Pierce and Jane survived, but in the wreckage found their only remaining son, 11-year-old Benjamin, crushed to death, his body nearly decapitated. Pierce was not able to hide the gruesome sight from Jane. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which likely affected Pierce's performance as president.[12] Jane wondered if the train accident was divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office. She wrote a lengthy letter of apology to "Benny" for her failings as a mother.[13] Jane would avoid social functions for much of her first two years as First Lady, making her public debut in that role to great sympathy at the public reception held at the White House on New Year's Day, 1855.[14]

Jane remained in New Hampshire as Pierce departed for his inauguration, which she did not attend. Pierce, the youngest man to be elected president to that point, chose to affirm his oath of office on a law book rather than swear it on a Bible, as all his predecessors except John Quincy Adams had done. He was the first president to deliver his inaugural address from memory.[15] In the address he hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of U.S. interests in its foreign relations, including the "eminently important" acquisition of new territories. "The policy of my Administration", said the new president, "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion." Avoiding the word "slavery", he emphasized his desire to put the "important subject" to rest and maintain a peaceful union. He alluded to his own personal tragedy, telling the crowd, "You have summoned me in my weakness, you must sustain me by your strength."[16]

Administration

Cabinet

| The Pierce Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

In his Cabinet appointments, Pierce sought to unite a party that was squabbling over the fruits of victory. Pierce sought to unite the party by appointing Democrats from all factions, including those that had not supported the Compromise of 1850. He anchored his cabinet around Attorney General Caleb Cushing, a pro-compromise northerner, and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, who had led Southern resistance to the compromise in the Senate. For the key position of Secretary of State, Pierce chose William L. Marcy, who had served as Secretary of War under President Polk. To appease the Cass and Buchanan wings of the party, Pierce appointed Secretary of the Interior Robert McClelland of Michigan and Postmaster General James Campbell of Pennsylvania, respectively. Pierce rounded out his geographically-balanced cabinet with Secretary of the Navy James C. Dobbin of North Carolina and Secretary of the Treasury James Guthrie. All initial cabinet appointees would remain in place throughout Pierce's presidency.[17]

All of Pierce's cabinet nominations were confirmed unanimously and immediately by the Senate.[18] Pierce spent the first few weeks of his term sorting through hundreds of lower-level federal positions to be filled. This was a chore, as he sought to represent all factions of the party, and could fully satisfy none of them. Partisans found themselves unable to secure positions for their friends, which put the Democratic Party on edge and fueled bitterness between factions. Before long, northern newspapers accused Pierce of filling his government with pro-slavery secessionists, while southern newspapers accused him of abolitionism.[18] Factionalism between the pro- and anti-administration Democrats ramped up quickly, especially within the New York Democratic Party. The more conservative Hardshell Democrats or "Hards" of New York were deeply skeptical of the Pierce administration, which was associated with Secretary of State Marcy and the more moderate New York faction, the Softshell Democrats or "Softs".[19]

Pierce sought to run a more efficient and accountable government than his predecessors.[20] His Cabinet members implemented an early system of civil service examinations which was a forerunner to the Pendleton Act passed three decades later.[21] The Interior Department was reformed by Secretary Robert McClelland, who systematized its operations, expanded the use of paper records, and pursued fraud.[22] Another of Pierce's reforms was to expand the role of the U.S. attorney general in appointing federal judges and attorneys, which was an important step in the eventual development of the Justice Department.[20]

Vice President

Pierce's running mate William R. King became severely ill with tuberculosis, and after the election he went to Cuba to recuperate. His condition deteriorated, and Congress passed a special law, allowing him to be sworn in before the American consul in Havana on March 24. Wanting to die at home, he returned to his plantation in Alabama on April 17 and died the next day.

The office of vice president remained vacant for the remainder of Pierce's term, as the Constitution then had no provision for filling it intra-term (prior to ratification of the Twenty-fifth Amendment in 1967). As such, the President pro tempore of the Senate, initially David Atchison of Missouri, was next in line to the presidency.[23]

Judicial appointments

There was a vacancy on the Supreme Court when Pierce took office, due to the death of John McKinley in 1852. President Fillmore had made several nominations to fill the vacancy before the end of his term, but his nominees were denied confirmation by the Senate. Pierce quickly nominated John Archibald Campbell, an advocate of states' rights, for the seat; this would be Pierce's only Supreme Court appointment.[24]

Pierce also appointed three judges to the United States circuit courts and twelve judges to the United States district courts. He was the first president to appoint judges to the United States Court of Claims.

Economic policy and internal improvements

Pierce frequently vetoed federally-funded internal improvements. The first bill he vetoed would have provided funding for mental asylums, a cause championed by reformer Dorothea Dix. In vetoing the bill, Pierce stated, "I cannot find any authority in the Constitution for making the Federal Government the great almoner of public charity throughout the United States." Reflecting this belief in a narrwoly-constructed constitution, Pierce also opposed federal funding for the completion of a transcontinental railroad. Pierce also called for a lowering of the Walker tariff, which had itself lowered the tariff rates to an historically low level, but it remained in place.[25]

Pierce charged Treasury Secretary James Guthrie with reforming the Treasury, which was inefficiently managed and had many unsettled accounts. Guthrie increased oversight of Treasury employees and tariff collectors, many of whom were withholding money from the government. Despite laws requiring funds to be held in the Treasury, large deposits remained in private banks under the Whig administrations. Guthrie reclaimed these funds and sought to prosecute corrupt officials, with mixed success.[26]

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, at Pierce's request, led surveys with the Corps of Topographical Engineers of possible transcontinental railroad routes throughout the country. The Democratic Party had long rejected federal appropriations for internal improvements, but Davis felt that such a project could be justified as a Constitutional national security objective. Davis also deployed the Army Corps of Engineers to supervise construction projects in the District of Columbia, including the expansion of the United States Capitol and building of the Washington Monument.[27]

Foreign and military affairs

The Pierce administration fell in line with the expansionist Young America movement, with William L. Marcy leading the charge as Secretary of State. Marcy sought to present to the world a distinctively American, republican image. He issued a circular recommending that U.S. diplomats wear "the simple dress of an American citizen" instead of the elaborate diplomatic uniforms worn in the courts of Europe, and that they only hire American citizens to work in consulates.[28] Marcy received international praise for his 73-page letter defending Austrian refugee Martin Koszta, who had been captured abroad in mid-1853 by the Austrian government despite his intention to become a U.S. citizen.[29]

Gadsden Purchase

Secretary of War Davis, an advocate of a southern transcontinental route, persuaded Pierce to send rail magnate James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land for a potential railroad. Gadsden was also charged with re-negotiating the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which required the U.S. to prevent Native American raids into Mexico from New Mexico Territory. Pierce authorized Gadsden to negotiate a treaty offering $50 million for large portions of Northern Mexico, including all of Baja California.[30] Gadsden concluded a less far-reaching treaty with Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna in December 1853, purchasing a portion of the Mexican state of Sonora. Negotiations were nearly derailed by William Walker's unauthorized expedition into Mexico, and so a clause was included charging the U.S. with combating future such attempts.[31] Congress reduced the Gadsden Purchase to the region now comprising southern Arizona and part of southern New Mexico; the price was cut from $15 million to $10 million. Congress also included a protection clause for a private citizen, Albert G. Sloo, whose interests were threatened by the purchase. Pierce opposed the use of the federal government to prop up private industry and did not endorse the final version of the treaty, which was ratified nonetheless.[32] The acquisition brought the contiguous United States to its present-day boundaries, excepting later minor adjustments.[33]

Relations with the British

Relations with the United Kingdom were tense due to disputes over American fishing rights in Canada and U.S. and British ambitions in Central America.[34] Marcy completed a trade reciprocity agreement with British minister to Washington, John Crampton, which would reduce the need for aggressive British naval patrols in Canadian waters. The treaty ratified in August 1854, which Pierce saw as a first step towards the American annexation of Canada.[35] While the administration negotiated with Britain over the Canada–US border, U.S. interests were also threatened in Central America, where the Clayton–Bulwer Treaty of 1850 had failed to keep Britain from expanding its influence. Pierce convinced former Secretary of State Buchanan to become the U.S. minister to Britain, and Buchanan sought to persuade Britain to relinquish their territories in Central America. After the start of the Crimean War, Pierce and Buchanan found success in convincing the British to pursue a new strategy in Central America.[36]

British consuls in the United States sought to enlist Americans for the Crimean War in 1854, in violation of neutrality laws, and Pierce eventually expelled minister Crampton and three consuls. To the President's surprise, the British did not expel Buchanan in retaliation. In his December 1855 message to Congress Pierce had set forth the American case that Britain had violated the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. The British, according to Buchanan, were impressed by the message and were rethinking their policy. Nevertheless, Buchanan was not successful in getting the British to renounce their Central American possessions. The Canadian treaty was ratified by Congress, the British Parliament, and by the colonial legislatures in Canada.[37]

Ostend Manifesto

Like many of his predecessors, Pierce hoped to annex the Spanish island of Cuba, which possessed wealthy sugar plantations, held a strategic position in the Caribbean, and represented the possibility of a new slave state. Pierce appointed Young America adherent Pierre Soulé as his minister to Spain, and Soulé quickly alienated the Spanish government.[38] After the Black Warrior Affair, in which the Spanish seized a U.S. merchant ship in Havana, the Pierce administration contemplated invading Cuba or aiding a filibuster expedition with the same intent, but the administration instead sought to buy Cuba from Spain.[39] Ambassadors Soulé, Buchanan, and John Y. Mason drafted a proposal to purchase Cuba from Spain for $120 million (USD), and justify the "wresting" of it from Spain if the offer were refused.[40] The document, essentially a position paper meant only for the consumption of the Pierce administration, did not offer any new thinking on the U.S. position towards Cuba and Spain, and was not intended to serve as a public edict.[41] But the publication of the Ostend Manifesto provoked the scorn of northerners who viewed it as an attempt to annex a slave-holding possession to bolster Southern interests. It helped discredit the expansionist policy of Manifest Destiny the Democratic Party had often supported.[40]

Other issues

Pierce favored expansion and a substantial reorganization of the military. Secretary of War Davis and Navy Secretary James C. Dobbin found the Army and Navy in poor condition, with insufficient forces, a reluctance to adopt new technology, and inefficient management.[42] Under the Pierce administration, Commodore Matthew C. Perry visited Japan (a venture originally planned under Fillmore) in an effort to expand trade to the East. Perry wanted to encroach on Asia by force, but Pierce and Dobbin pushed him to remain diplomatic. Perry signed a modest trade treaty with the Japanese shogunate which was successfully ratified.[43] The 1856 launch of the USS Merrimac, one of six newly commissioned steam frigates, was one of Pierce's "most personally satisfying" days in office.[44]

The slavery debate and Bleeding Kansas

In his inaugural address, Pierce expressed hope that the Compromise of 1850 would end the issue of slavery in the territories. The compromise had allowed slavery in Utah Territory and New Mexico Territory, which had been acquired in the Mexican-American War. The Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery in territories north of the 36°30′ parallel, remained in place for the other U.S. territories, including the vast unorganized territory consisting of much of the land acquired in the Louisiana Purchase. The territory was often referred to as "Nebraska" (the territory encompassed much more than the state of Nebraska, which would join the union in 1867). As settlers poured into the area, and commercial and political interests called for a transcontinental railroad through the region, pressure mounted for the organization of the eastern parts of the unorganized territory. But the issue of slavery would complicate any territorial organization.[45]

Organizing the territory was necessary for settlement as the land would not be surveyed nor put up for sale until a territorial government was authorized. Those from slave states had never been content with western limits on slavery, and felt that slavery should be able to expand into territories, while many Northerners would expose any such expansion. Senator Stephen Douglas and his allies planned to organize the territory and let local settlers decide whether to allow slavery. This would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820, as most of land in question was north of the 36°30′ parallel. Two new territories would be created: Kansas Territory would be located to the west of Missouri, while Nebraska Territory would be located north of Kansas Territory. The expectation was that the people of the Nebraska Territory would not allow slavery, while the people of the Kansas Territory would allow slavery.[46]

_-_Geographicus_-_NebraskaKansas-colton-1855.jpg)

Pierce had wanted to organize the Nebraska Territory without explicitly addressing the matter of slavery, but Douglas could not get enough southern support to accomplish this.[47] Pierce was skeptical of the bill, knowing it would result in bitter opposition from the North. Douglas and Davis convinced him to support the bill regardless. It was tenaciously opposed by northerners such as Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase and Massachusetts' Charles Sumner, who rallied public sentiment in the North against the bill. Northerners had been suspicious of the Gadsden Purchase, moves towards Cuba annexation, and the influence of slaveholding Cabinet members such as Davis, and saw the Nebraska bill as part of a pattern of southern aggression. The result was a political firestorm that did great damage to Pierce's presidency.[46]

Pierce and his administration used threats and promises to keep most Democrats on board in favor of the bill. The Whigs split along sectional lines, and the conflict finally destroyed the ailing party. The Kansas–Nebraska Act was passed in May 1854 and would come to define the Pierce presidency. The political turmoil that followed the passage saw the short-term rise of the nativist and anti-Catholic American Party, often called the Know Nothings, and the founding of the Republican Party.[46]

Even as the act was being debated, settlers on both sides of the slavery issue poured into the territories so as to secure the outcome they wanted in the voting. The passage of the act resulted in so much violence between groups that the territory became known as Bleeding Kansas. Thousands of pro-slavery Border Ruffians came across from Missouri to vote in the territorial elections although they were not resident in Kansas, giving that element the victory. Pierce supported the outcome despite the irregularities. When Free-Staters set up a shadow government, and drafted the Topeka Constitution, Pierce called their work an act of rebellion. The president continued to recognize the pro-slavery legislature, which was dominated by Democrats, even after a Congressional investigative committee found its election to have been illegitimate. He dispatched federal troops to break up a meeting of the Topeka government.[49]

Passage of the act coincided with the seizure of escaped slave Anthony Burns in Boston. Northerners rallied in support of Burns, but Pierce was determined to follow the Fugitive Slave Act to the letter, and dispatched federal troops to enforce Burns' return to his Virginia owner despite furious crowds.[50]

Partisan re-alignment

The Whig Party was devastated by the 1852 elections, and upon entering office, Pierce was as concerned about intra-party opposition as he was about the Whigs. The Compromise of 1850 had split both major parties along geographic lines. In several Northern states, some Democrats opposed to the compromise had joined with Free Soil Party to take control of state governments. In the South, many state parties had also been split by the compromise. Hoping to keep his own party unified, Pierce appointed both supporters and opponents of the Compromise of 1850 from both the North and South. This policy infuriated both supporters and opponents of the compromise, particularly in the South. Allies of former President Fillmore sought the creation of a Union Party consisting of pro-compromise Democrats and Whigs, and many Democrats worried that their party would suffer the fate of the Whigs.[51]

Yet it was the Kansas-Nebraska Act, rather than the Compromise of 1850, that would serve as the catalyst to partisan re-alignment. Pierce demanded that all loyal Democrats support the act, hoping that the Kansas-Nebraska Act and debates over the development of the West would reinvigorate partisan conflict and distract from intra-party battles. But the bill instead polarized legislators sectional lines, with Southern Whigs providing critical votes in the House as a narrow majority of Northern Democrats voted against it. Congressional Democrats suffered huge losses in the mid-term elections of 1854, voting instead for a wide array of new parties opposed to the Democrats and the Kansas-Nebraska Act. In many Midwestern states, a coalition of Free Soilers and Northern Whigs, many of whom were no longer willing to cooperate with Southern Whigs in the aftermath of the latter's support of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, formed a new coalition that became known as the Republican Party. The party lambasted the institution of slavery and opposed the Fugitive Slave Act and the extension of slavery into the territories. In other Midwestern states, opponents of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Democratic Party merely labeled themselves the "Opposition." In other parts of the country, many Whigs refused to abandon their party. But the Know Nothing movement, seizing on growing fears of Catholic immigrants, defeated numerous Northeastern and Southern congressional candidates from both the Whig and Democratic parties.[52] In Pierce's home state of New Hampshire, hitherto loyal to the Democratic Party, the Know-Nothings elected the governor, all three representatives, dominated the legislature, and returned John P. Hale to the Senate.[48] The elections left Democrats in the minority in the House, although they retained control of the Senate.[52] Nathaniel Banks, a member of the Know Nothings and the Free Soil Party, won election as Speaker of the House after a protracted battle.[53]

In the aftermath of the elections, the Know Nothings met in Philadelphia, where they changed their name to the American Party. With support in both the North and South, the Know Nothings loomed as a potential replacement for the Whigs as the main opposition for the Democrats, but the fledgling party split along sectional lines over a proposed restoration of the Missouri Compromise. As the controversy over Kansas continued, Know Nothings, Whigs, and even Democrats became increasingly attracted to the Republican Party. The election of Nathaniel Banks, who was sympathetic to Republican ideals and opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, confirmed the growing national power of the Republicans. Pierce declared his full opposition the new party, decrying what he saw as its anti-southern stance, but his perceived pro-Southern actions in Kansas continued to inflame Northern anger. The Know Nothing National Convention alienated many Northern Know Nothings by nominating former President Fillmore for another term and failing to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Fillmore also received the presidential nomination at sparsely attended 1856 Whig convention. The 1856 Republican National Convention nominated John C. Frémont, and many Northern Know Nothings came to back Frémont instead of Fillmore. As the 1856 election would show, the Republicans had become the main opposition to the Democratic Party in the North.[54]

Election of 1856 and transition

As the 1856 election approached, many Democrats spoke of replacing Pierce with Buchanan or Douglas, but Pierce retained the support of his cabinet and many others within the party. Pierce maintained strong support among Southern Democrats, as well as some support in his native New England. But other Northern Democrats opposed Pierce, who had become strongly associated with the unpopular Kansas-Nebraska Act. Buchanan, who had been outside of the country since 1853 and thus could not be associated with the act, became the candidate of many Northern Democrats.[55]

When balloting began on June 5 at the convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, Pierce expected a plurality, if not the required two-thirds majority. On the first ballot, he received only 122 votes, many of them from the South, to Buchanan's 135, with Douglas and Cass receiving the rest. By the following morning fourteen ballots had been completed, but none of the three main candidates were able to get two-thirds of the vote. Pierce, whose support had been slowly declining as the ballots passed, directed his supporters to break for Douglas, withdrawing his name in a last-ditch effort to defeat Buchanan. Douglas, only 43 years of age, believed that he could be nominated in 1860 if he let the older Buchanan win this time, and received assurances from Buchanan's managers that this would be the case. After two more deadlocked ballots, Douglas's managers withdrew his name, leaving Buchanan as the clear winner. To soften the blow to Pierce, the convention issued a resolution of "unqualified approbation" in praise of his administration and selected his ally, former Kentucky Representative John C. Breckinridge, as the vice-presidential nominee.[56] This loss marked the only time in U.S. history that an elected president who was an active candidate for reelection was not nominated for a second term.[57]

Pierce endorsed Buchanan, though the two remained distant; he hoped to resolve the Kansas situation by November to improve the Democrats' chances in the general election. He installed John W. Geary as territorial governor, who drew the ire of pro-slavery legislators.[58] Geary was able to restore order in Kansas, though the electoral damage had already been done—Republicans used "Bleeding Kansas" and "Bleeding Sumner" (the brutal caning of Charles Sumner by South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks in the Senate chamber) as election slogans.[59] The Buchanan/Breckinridge ticket was elected, but Buchanan won only five of sixteen free states (Pierce had won fourteen). Frémont, the Republican nominee, won the remaining eleven free states, while Fillmore won just Maryland. In the North, the Democratic share of the popular vote fell from Pierce's 49.8% in 1852 to just 41.4%. The strong Republican showing confirmed that they, and not the Know Nothings, would replace the Whigs as the main opposition to the Democrats.[60]

Pierce did not temper his rhetoric after losing the nomination. In his final message to Congress, delivered in December 1856, he blamed anti-salvery activists for Bleeding Kansas and vigorously attacked the Republican Party as a threat to the unity of the nation.[61] He also took the opportunity to defend his record on fiscal policy, and on achieving peaceful relations with other nations.[62] In the final days of the Pierce administration, Congress passed bills to increase the pay of army officers and to build new naval vessels, also expanding the number of seamen enlisted. It also passed a tariff reduction bill he had long sought.[63] During the transition period, Pierce avoided criticizing Buchanan, who he had long disliked, but was angered by Buchanan's decision to assemble an entirely new cabinet.[64] Pierce and his cabinet left office on March 4, 1857, the only time in U.S. history that the original cabinet members all remained for a full four-year term.[65]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 181–84; Gara (1991), pp, 23–29.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 184–97; Gara (1991), pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 197–202; Gara (1991), pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 210–13; Gara (1991), pp. 36–38. Quote from Gara, 38.

- ↑ Holt (2010), loc. 724.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 231; Gara (1991), p. 38, Holt (2010), loc. 725.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 206; Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ↑ Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 203.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 229–30; Gara (1991), p. 39.

- ↑ Holt (2010), loc. 740.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 241–49; Gara (1991), pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 241–49.

- ↑ Boulard (2006), p. 55.

- ↑ Hurja, Emil (1933). History of Presidential Inaugurations. New York Democrat. p. 49.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 249–55.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 48-52

- 1 2 Wallner (2007), pp. 5–24.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 15–18, and throughout.

- 1 2 Wallner (2007), p. 20.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 36–39.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. p. 21–22.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), p. 10.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 53-54, 71.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 32–36.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 40–41, 52.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 25–32; Gara (1991), p. 128.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 61–63; Gara (1991), pp. 128–29.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 75–81; Gara (1991), pp. 129–33.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 106–08; Gara (1991), pp. 129–33.

- ↑ Holt, loc. 872.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 27–30, 63–66, 125–26; Gara (1991), p. 133.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Holt (2010), loc. 902–17.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 59-60.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 60-62.

- 1 2 Wallner (2007), pp. 131–57; Gara (1991), pp. 149–55.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 63-65.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 40–43.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), p. 172; Gara (1991), pp. 134–35.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), p. 256.

- ↑ Holt, pp. 53-54, 72-73

- 1 2 3 Wallner (2007), pp. 90–102, 119–22; Gara (1991), pp. 88–100, Holt (2010), loc. 1097–1240.

- ↑ Etchison, p. 14.

- 1 2 Wallner (2007), pp. 158–67; Gara (1991), pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 195–209; Gara (1991), pp. 111–20.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 122–25; Gara (1991), pp. 107–09.

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 47-48, 66-70

- 1 2 Holt (2010), pp. 78-89

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 92-93

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 91-94, 99, 106-109

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 94-96

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 266–70; Gara (1991), pp. 157–67, Holt (2010), loc. 1515–58.

- ↑ Rudin, Ken (July 22, 2009). "When Has A President Been Denied His Party's Nomination?". NPR. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 272–80.

- ↑ Holt (2010), loc. 1610.

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 109-110

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 110-114

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 292–96; Gara (1991), pp. 177–79.

- ↑ Wallner (2007), pp. 303–04.

- ↑ Holt (2010), pp. 110-114

- ↑ Wallner (2007), p. 305.

Sources

- Boulard, Garry (2006). The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce: The Story of a President and the Civil War. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 0-595-40367-0.

- Butler, Pierce (1908). Judah P. Benjamin. American Crisis Biographies. George W. Jacobs & Company. OCLC 664335.

- Etchison, Nicole (2004). Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-1287-4.

- Gara, Larry (1991). The Presidency of Franklin Pierce. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0494-4.

- Holt, Michael F. (2010). Franklin Pierce. The American Presidents (Kindle ed.). Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 978-0-8050-8719-2.

- Wallner, Peter A. (2004). Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son. Plaidswede. ISBN 0-9755216-1-6.

- Wallner, Peter A. (2007). Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union. Plaidswede. ISBN 978-0-9790784-2-2.

Further reading

- Allen, Felicity (1999). Jefferson Davis, Unconquerable Heart. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1219-0.

- Barlett, D.W. (1852). The life of Gen. Frank. Pierce, of New Hampshire, the Democratic candidate for president of the United States. Derby & Miller. OCLC 1742614.

- Bergen, Anthony (May 30, 2015). "In Concord: The Friendship of Pierce and Hawthorne". Medium.

- Brinkley, A; Dyer, D (2004). The American Presidency. Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-38273-9.

- Hawthorne, Nathaniel (1852). The Life of Franklin Pierce. Ticknor, Reed and Fields. OCLC 60713500.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin (1923). The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854. Columbia University Press. OCLC 2512393.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin (1931). Franklin Pierce, Young Hickory of the Granite Hills. University of Pennsylvania Press. OCLC 426247.

- Potter, David M. (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-013403-8.

- Silbey, Joel H. (2014). A Companion to the Antebellum Presidents 1837–1861. Wiley. pp 345–96

- Taylor, Michael J.C. (2001). "Governing the Devil in Hell: 'Bleeding Kansas' and the Destruction of the Franklin Pierce Presidency (1854–1856)". White House Studies. 1: 185–205.

External links

- Works by Franklin Pierce at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Franklin Pierce at Internet Archive

- Essays on Franklin Pierce and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady, from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Franklin Pierce: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Biography from the White House

- Franklin Pierce Bicentennial

- "Life Portrait of Franklin Pierce", from C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits, June 14, 1999

- "Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son"—Booknotes interview with Peter Wallner, November 28, 2004

- Franklin Pierce Personal Manuscripts

| U.S. Presidential Administrations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Fillmore |

Pierce Presidency 1853–1857 |

Succeeded by Buchanan |

.jpg)