Pick's theorem

Given a simple polygon constructed on a grid of equal-distanced points (i.e., points with integer coordinates) such that all the polygon's vertices are grid points, Pick's theorem provides a simple formula for calculating the area A of this polygon in terms of the number i of lattice points in the interior located in the polygon and the number b of lattice points on the boundary placed on the polygon's perimeter:[1]

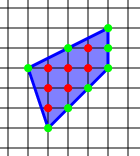

In the example shown, we have i = 7 interior points and b = 8 boundary points, so the area is A = 7 + 8/2 − 1 = 7 + 4 − 1 = 10 square units.

Note that the theorem as stated above is only valid for simple polygons, i.e., ones that consist of a single piece and do not contain holes. For a polygon that has h holes, with a boundary in the form of h + 1 simple closed curves, the slightly more complicated formula i + b/2 + h − 1 gives the area.

The result was first described by Georg Alexander Pick in 1899.[2] The Reeve tetrahedron shows that there is no analogue of Pick's theorem in three dimensions that expresses the volume of a polytope by counting its interior and boundary points. However, there is a generalization in higher dimensions via Ehrhart polynomials. The formula also generalizes to surfaces of polyhedra.

Proof

Consider a polygon P and a triangle T, with one edge in common with P. Assume Pick's theorem is true for both P and T separately; we want to show that it is also true for the polygon PT obtained by adding T to P. Since P and T share an edge, all the boundary points along the edge in common are merged to interior points, except for the two endpoints of the edge, which are merged to boundary points. So, calling the number of boundary points in common c, we have[3]

and

From the above follows

and

Since we are assuming the theorem for P and for T separately,

Therefore, if the theorem is true for polygons constructed from n triangles, the theorem is also true for polygons constructed from n + 1 triangles. For general polytopes, it is well known that they can always be triangulated. That this is true in dimension 2 is an easy fact. To finish the proof by mathematical induction, it remains to show that the theorem is true for triangles. The verification for this case can be done in these short steps:

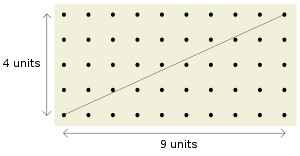

- observe that the formula holds for any unit square (with vertices having integer coordinates);

- deduce from this that the formula is correct for any rectangle with sides parallel to the axes;

- deduce it, now, for right-angled triangles obtained by cutting such rectangles along a diagonal;

- now any triangle can be turned into a rectangle by attaching such right triangles; since the formula is correct for the right triangles and for the rectangle, it also follows for the original triangle.

The last step uses the fact that if the theorem is true for the polygon PT and for the triangle T, then it's also true for P; this can be seen by a calculation very much similar to the one shown above.

See also

References

- ↑ Trainin, J. (November 2007). "An elementary proof of Pick's theorem". Mathematical Gazette. 91 (522): 536–540.

- ↑ Pick, Georg (1899). "Geometrisches zur Zahlenlehre". Sitzungsberichte des deutschen naturwissenschaftlich-medicinischen Vereines für Böhmen "Lotos" in Prag. (Neue Folge). 19: 311–319. JFM 33.0216.01. CiteBank:47270

- ↑ Beck, Matthias; Robins, Sinai (2007). Computing the Continuous Discretely, Integer-point enumeration in polyhedra. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. New York: Springer-Verlag. ch. 2. ISBN 978-0-387-29139-0. MR 2271992.

External links

- Pick's Theorem (Java) at cut-the-knot

- Pick's Theorem

- Pick's Theorem proof by Tom Davis

- Pick's Theorem by Ed Pegg, Jr., the Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Pick's Theorem". MathWorld.