Phthalate

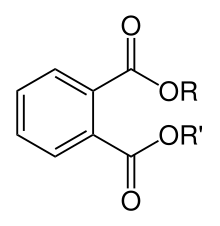

Phthalates (US: /ˈθæleɪts/,[1] UK: /ˈθɑːleɪts/[2]), or phthalate esters, are esters of phthalic acid and are mainly used as plasticizers (substances added to plastics to increase their flexibility, transparency, durability, and longevity). Phthalates are manufactured by reacting phthalic anhydride with alcohol(s) that range from methanol and ethanol (C1/C2) up to tridecyl alcohol (C13), either as a straight chain or with some branching. They are divided into two distinct groups, with very different applications, toxicological properties, and classification, based on the number of carbon atoms in their alcohol chain. They are used primarily to soften polyvinyl chloride (PVC). Lower-molecular-weight phthalates (3-6 carbon atoms in their backbone) are being gradually replaced in many products in the United States, Canada, and European Union over health concerns.[3][4] They are replaced by high-molecular-weight phthalates (those with more than 6 carbons in their backbone, which gives them increased permanency and durability). In 2010, the market was still dominated by high-phthalate plasticizers; however, due to legal provisions and growing environmental awareness and perceptions, producers are increasingly forced to use non-phthalate plasticizers.[5]

Phthalates are used in a wide range of common products, and are released into the environment.[6] There is no covalent bond between the phthalates and plastics; rather, they are entangled within the plastic as a result of the manufacturing process used to make PVC articles.[7] They can be removed by exposure to heat or with organic solvents. Due to the ubiquity of plastics (and therefore plasticizers) in modern life, the vast majority of people are exposed to some level of phthalates, and most Americans tested by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have metabolites of multiple phthalates in their urine.[8] Phthalate exposure may be through direct use or by indirect means through leaching and general environmental contamination. Diet is believed to be the main source of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) and other phthalates in the general population.[8] Fatty foods such as milk, butter, and meats are a major source.[9] In studies of rodents exposed to certain phthalates, high doses have been shown to change hormone levels and cause birth defects.[10]

Uses

Phthalates are used in a large variety of products, from enteric coatings of pharmaceutical pills and nutritional supplements to viscosity control agents, gelling agents, film formers, stabilizers, dispersants, lubricants, binders, emulsifying agents, and suspending agents. End-applications include adhesives and glues, agricultural adjuvants, building materials, personal-care products, medical devices, detergents and surfactants, packaging, children's toys, modelling clay, waxes, paints, printing inks and coatings, pharmaceuticals, food products, and textiles. Phthalates are also frequently used in soft plastic fishing lures, caulk, paint pigments, and sex toys made of so-called "jelly rubber". Phthalates are used in a variety of household applications such as shower curtains, vinyl upholstery, adhesives, floor tiles, food containers and wrappers, and cleaning materials. Personal-care items containing phthalates include perfume, eye shadow, moisturizer, nail polish, liquid soap, and hair spray.[11]

Phthalates are also found in modern electronics and medical applications such as catheters and blood transfusion devices. The most widely used phthalates are di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP), and diisononyl phthalate (DINP). DEHP was the dominant plasticizer used globally in PVC due to its low cost. Benzylbutylphthalate (BBP) is used in the manufacture of foamed PVC, which is used mostly as a flooring material, though its use is decreasing rapidly in the Western countries. Phthalates with small R and R' groups are used as solvents in perfumes and pesticides.

Approximately 8.4 million tonnes of plasticizers are consumed globally every year, of which European consumption accounts for approximately 1.5 million metric tonnes.[12] Approximately 70% of those totals are phthalates, down from about 88% in 2005. The remaining 30% are alternative chemistries. Plasticizers contribute 10-60% of total weight of plasticized products. More recently in Europe and the US, regulatory developments have resulted in a change in phthalate consumption, with the higher phthalates (DINP and DIDP) replacing DEHP as the general purpose plasticizer of choice because DIDP and DINP were not classified as hazardous. All of these mentioned phthalates are now regulated and restricted in many products. DEHP, although most applications are shown to pose no risk when studied using recognized methods of risk assessment, has been classified as a Category 1B reprotoxin, [13] and is now on the Annex XIV of the European Union's REACH legislation, which means that producers and users must submit authorization requests to the European Chemicals Agency in Helsinki to continue to use DEHP. Analysis of such applications will involve studies on alternatives and, given the wide number of compounds that have been used as plasticizers, such evaluations are likely to be far-reaching.

History

The development of cellulose nitrate plastic in 1846 led to the patent of castor oil in 1856 for use as the first plasticizer. In 1870, camphor became the more favored plasticizer for cellulose nitrate. Phthalates were first introduced in the 1920s and quickly replaced the volatile and odorous camphor. In 1931, the commercial availability of polyvinyl chloride and the development of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate began the boom of the plasticizer PVC industry.

Properties

Phthalate esters are the dialkyl or alkyl aryl esters of phthalic acid (also called 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, not be confused with the structurally isomeric terephthalic or isophthalic acids ); the name "phthalate" derives from phthalic acid, which itself is derived from the word "naphthalene". When added to plastics, phthalates allow the long polyvinyl molecules to slide against one another. The phthalates have a clear syrupy liquid consistency and show low water solubility, high oil solubility, and low volatility. The polar carboxyl group contributes little to the physical properties of the phthalates, except when R and R' are very small (such as ethyl or methyl groups). Phthalates are colorless, odorless liquids produced by reacting phthalic anhydride with an appropriate alcohol (usually 6- to 13-carbon).

The mechanism by which phthalates and other molecules afford plasticization to polar polymers has been a subject of intense study since the 1960s. The mechanism is one of polar interactions between the polar centres of the phthalate molecule (the C=O functionality) and the positively charged areas of the vinyl chain, typically residing on the carbon atom of the carbon-chlorine bond. For this to be established, the polymer must be heated in the presence of the plasticizer, first above the Tg of the polymer and then into a melt state. This enables an intimate mix of polymer and plasticizer to be formed, and for these interactions to occur. When cooled, these interactions remain and the network of PVC chains cannot reform (as is present in unplasticized PVC, or PVC-U). The alkyl chains of the phthalate then screen the PVC chains from each other as well.

Alternatives

There are numerous biological alternatives on the market. The problem is that they are typically expensive and not compatible as a primary plasticizer. However, Dioctyl terephthalate (a terephthalate isomeric with DEHP) and 1,2-Cyclohexane dicarboxylic acid diisononyl ester (a hydrogenated version of DINP) are available at cost-competitive pricing and with good plasticization properties.

A plasticizer based on vegetable oil that uses single reactor synthesis and is compatible as a primary plasticizer has been developed. It is a ready substitute for dioctyl phthalate.[14] And several other bio-based plasticizers have been and are being developed as alternatives to phthalates.

Table of the most common phthalates

| Name | Abbreviation | Structural formula | Molecular weight (g/mol) | CAS No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl phthalate | DMP | C6H4(COOCH3)2 | 194.18 | 131-11-3 |

| Diethyl phthalate | DEP | C6H4(COOC2H5)2 | 222.24 | 84-66-2 |

| Diallyl phthalate | DAP | C6H4(COOCH2CH=CH2)2 | 246.26 | 131-17-9 |

| Di-n-propyl phthalate | DPP | C6H4[COO(CH2)2CH3]2 | 250.29 | 131-16-8 |

| Di-n-butyl phthalate | DBP | C6H4[COO(CH2)3CH3]2 | 278.34 | 84-74-2 |

| Diisobutyl phthalate | DIBP | C6H4[COOCH2CH(CH3)2]2 | 278.34 | 84-69-5 |

| Butyl cyclohexyl phthalate | BCP | CH3(CH2)3OOCC6H4COOC6H11 | 304.38 | 84-64-0 |

| Di-n-pentyl phthalate | DNPP | C6H4[COO(CH2)4CH3]2 | 306.40 | 131-18-0 |

| Dicyclohexyl phthalate | DCP | C6H4[COOC6H11]2 | 330.42 | 84-61-7 |

| Butyl benzyl phthalate | BBP | CH3(CH2)3OOCC6H4COOCH2C6H5 | 312.36 | 85-68-7 |

| Di-n-hexyl phthalate | DNHP | C6H4[COO(CH2)5CH3]2 | 334.45 | 84-75-3 |

| Diisohexyl phthalate | DIHxP | C6H4[COO(CH2)3CH(CH3)2]2 | 334.45 | 146-50-9 |

| Diisoheptyl phthalate | DIHpP | C6H4[COO(CH2)4CH(CH3)2]2 | 362.50 | 41451-28-9 |

| Butyl decyl phthalate | BDP | CH3(CH2)3OOCC6H4COO(CH2)9CH3 | 362.50 | 89-19-0 |

| Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | DEHP, DOP | C6H4[COOCH2CH(C2H5)(CH2)3CH3]2 | 390.56 | 117-81-7 |

| Di(n-octyl) phthalate | DNOP | C6H4[COO(CH2)7CH3]2 | 390.56 | 117-84-0 |

| Diisooctyl phthalate | DIOP | C6H4[COO(CH2)5CH(CH3)2]2 | 390.56 | 27554-26-3 |

| n-Octyl n-decyl phthalate | ODP | CH3(CH2)7OOCC6H4COO(CH2)9CH3 | 418.61 | 119-07-3 |

| Diisononyl phthalate | DINP | C6H4[COO(CH2)6CH(CH3)2]2 | 418.61 | 28553-12-0 |

| Di(2-propylheptyl) phthalate | DPHP | C6H4[COOCH2CH(CH2CH2CH3)(CH2)4CH3]2 | 446.66 | 53306-54-0 |

| Diisodecyl phthalate | DIDP | C6H4[COO(CH2)7CH(CH3)2]2 | 446.66 | 26761-40-0 |

| Diundecyl phthalate | DUP | C6H4[COO(CH2)10CH3]2 | 474.72 | 3648-20-2 |

| Diisoundecyl phthalate | DIUP | C6H4[COO(CH2)8CH(CH3)2]2 | 474.72 | 85507-79-5 |

| Ditridecyl phthalate | DTDP | C6H4[COO(CH2)12CH3]2 | 530.82 | 119-06-2 |

| Diisotridecyl phthalate | DITP | C6H4[COO(CH2)10CH(CH3)2]2 | 530.82 | 68515-47-9 |

Environmental impact

Phthalates are easily released into the environment.[6] In general, they do not persist in the outdoor environment due to biodegradation, photodegradation, and anaerobic degradation. Outdoor air concentrations are higher in urban and suburban areas than in rural and remote areas.[11]

In general, indoor air concentrations are higher than outdoor air concentrations due to the nature of the sources. Because of their volatility, DEP and DMP are present in higher concentrations in air in comparison with the heavier and less volatile DEHP. Higher air temperatures result in higher concentrations of phthalates in the air. PVC flooring leads to higher concentrations of BBP and DEHP, which are more prevalent in dust.[11] A 2012 Swedish study of children found that phthalates from PVC flooring were taken up into their bodies, showing that children can ingest phthalates not only from food but also by breathing and through the skin.[15]

Diet is believed to be the main source of DEHP and other phthalates in the general population. Fatty foods such as milk, butter, and meats are a major source. Studies show that exposure to phthalates is greater from ingestion of certain foods, rather than exposure via water bottles as is most often first thought of with plastic chemicals.[16] Low-molecular-weight phthalates such as DEP, DBP, BBzP may be dermally absorbed. Inhalational exposure is also significant with the more volatile phthalates.[17] Another study, conducted between 2003 and 2010 analysing data from 9,000 individuals, from those reported that had eaten at a fast food restaurant were found with much higher levels of two separate phthalates - DEHP and DiNP - in their urine samples. Interestingly, even small consumption of fast food caused higher presence of phthalates. 'People who reported eating only a little fast food had DEHP levels that were 15.5 percent higher and DiNP levels that were 25 percent higher than those who said they had eaten none. For people who reported eating a sizable amount, the increase was 24 percent and 39 percent, respectively.'[18]

In a 2008 Bulgarian study, higher dust concentrations of DEHP were found in homes of children with asthma and allergies, compared with healthy children's homes.[19] The author of the study stated, "The concentration of DEHP was found to be significantly associated with wheezing in the last 12 months as reported by the parents."[19] Phthalates were found in almost every sampled home in Bulgaria. The same study found that DEHP, BBzP, and DnOP were in significantly higher concentrations in dust samples collected in homes where polishing agents were used. Data on flooring materials was collected, but there was not a significant difference in concentrations between homes where no polish was used that have balatum (PVC or linoleum) flooring and homes with wood. High frequency of dusting did decrease the concentration.[19]

In general, children's exposure to phthalates is greater than that of adults. In a 1990s Canadian study that modeled ambient exposures, it was estimated that daily exposure to DEHP was 9 μg/kg bodyweight/day in infants, 19 μg/kg bodyweight/day in toddlers, 14 μg/kg bodyweight/day in children, and 6 μg/kg bodyweight/day in adults.[17] Infants and toddlers are at the greatest risk of exposure, because of their mouthing behavior. Body-care products containing phthalates are a source of exposure for infants. The authors of a 2008 study "observed that reported use of infant lotion, infant powder, and infant shampoo were associated with increased infant urine concentrations of [phthalate metabolites], and this association is strongest in younger infants. These findings suggest that dermal exposures may contribute significantly to phthalate body burden in this population." Though they did not examine health outcomes, they noted that "Young infants are more vulnerable to the potential adverse effects of phthalates given their increased dosage per unit body surface area, metabolic capabilities, and developing endocrine and reproductive systems."[20]

Infants and hospitalized children are particularly susceptible to phthalate exposure. Medical devices and tubing may contain 20-40% Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) by weight, which "easily leach out of tubing when heated (as with warm saline/blood) ".[21] Several medical devices contain phthalates including, but not limited to, IV tubing, gloves, nasogastric tubes and respiratory tubing. The Food and Drug Administration did an extensive risk assessment of phthalates in the medical setting and found that neonates may be exposed to five times greater than the allowed daily tolerable intake. This finding led to the conclusion by the FDA that, "Children undergoing certain medical procedures may represent a population at increased risk for the effects of DEHP." [21]

In 2008, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found a variety of phthalates in erasers and warned of health risks when children regularly suck and chew on them. The European Commission Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER), however, considers that, even in the case when children bite off pieces from erasers and swallow them, it is unlikely that this exposure leads to health consequences.[22]

Phthalates are also found in medications, where they are used as inactive ingredients in producing enteric coatings. It is not known how many medications are made using phthalates, but some include omeprazole, didanosine, mesalamine, and theophylline. A recent study found that urinary concentrations of monobutyl phthalate, the DBP metabolite, of Asacol (a particular formulation of mesalamine) users was 50 times higher than the mean of nonusers.[23] The study showed that exposures from phthalate-containing medications can far exceed population levels from other sources.[23] DBP in medications raises concern about health risks due to the high level of exposures associated with taking these medications, especially in vulnerable segments of the population, including pregnant women and children.[23]

In 2008, the United States National Research Council recommended that the cumulative effects of phthalates and other antiandrogens be investigated. It criticized US EPA guidances, which stipulate that, when examining cumulative effects, the chemicals examined should have similar mechanisms of action or similar structures, as too restrictive. It recommended instead that the effects of chemicals that cause similar adverse outcomes should be examined cumulatively.[24] Thus, the effect of phthalates should be examined together with other antiandrogens, which otherwise may have been excluded because their mechanisms or structure are different.

Health effects

Endocrine disruption

Several phthalates are "plausibly" endocrine disruptors.[25] The long-term health effects of exposure to endocrine disruptors, such as phthalates, are unclear.[26]

Authors of a 2006 study of boys with undescended testis hypothesized that exposure to a combination of phthalates and anti-androgenic pesticides may have contributed to that condition.[27]

A scientific review in 2013 came to the conclusion that epidemiological and in vitro studies generally converge sufficiently to conclude that phthalate anti-androgenicity is plausible in adult men.[25]

Endocannabinoid system disruption

Phthalates block CB1 as allosteric antagonists.[28]

Other effects

There may be a link between the obesity epidemic and endocrine disruption and metabolic interference. Studies conducted on mice exposed to phthalates in utero did not result in metabolic disorder in adults.[29] However, "in a national cross-section of U.S. men, concentrations of several prevalent phthalate metabolites showed statistically significant correlations with abnormal obesity and insulin resistance."[29] Mono-ethylhexyl-phthalate (MEHP), a metabolite of DEHP, has been found to interact with all three peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs).[29] PPARs are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. The author of the study stated "The roles of PPARs in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism raise the question of their activation by a sub-class of pollutants, tentatively named metabolic disrupters."[29] Phthalates belong to this class of metabolic disruptors. It is a possibility that, over many years of exposure to these metabolic disruptors, they are able to deregulate complex metabolic pathways in a subtle manner.[29]

Large amounts of specific phthalates fed to rodents have been shown to damage their liver and testes,[10] and initial rodent studies also indicated hepatocarcinogenicity. Following this result, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate was listed as a possible carcinogen by IARC, EC, and WHO. Later studies on primates showed that the mechanism is specific to rodents - humans are resistant to the effect.[30] The carcinogen classification was subsequently withdrawn.

Legal status

European Union

The use of some phthalates has been restricted in the European Union for use in children's toys since 1999.[31] DEHP, BBP, and DBP are restricted for all toys; DINP, DIDP, and DNOP are restricted only in toys that can be taken into the mouth. The restriction states that the amount of these phthalates may not be greater than 0.1% mass percent of the plasticized part of the toy. Generally the high molecular weight phthalates DINP, DIDP and DPHP have been registered under REACH (see below) and have demonstrated their safety for use in current applications. They are not classified for any health or environmental effects.

The low molecular weight products BBP, DEHP, DIBP, and DBP were added to the Candidate list of Substances for Authorisation under REACH in 2008-9, and added to the Authorisation list, Annex XIV, in 2012.[3] This means that from February 2015 they are not allowed to be produced in the EU unless authorisation has been granted for a specific use, however they may still be imported in consumer products.[32] The creation of an Annex XV dossier, which could ban the import of products containing these chemicals, is being jointly prepared by the ECHA and Danish authorities and is expected to be submitted by April 2016.[33]

The Dutch office of Greenpeace UK sought to encourage the European Union to ban sex toys that contained phthalates.[34]

United States

During August 2008, the United States Congress passed and President George W. Bush signed the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA), which became public law 110-314.[35] Section 108 of that law specified that as of February 10, 2009, "it shall be unlawful for any person to manufacture for sale, offer for sale, distribute in commerce, or import into the United States any children's toy or child care article that contains concentrations of more than 0.1 percent of" DEHP, DBP, or BBP and "it shall be unlawful for any person to manufacture for sale, offer for sale, distribute in commerce, or import into the United States any children's toy that can be placed in a child's mouth or child care article that contains concentrations of more than 0.1 percent of" DINP, DIDP, DnOP. Furthermore, the law requires the establishment of a permanent review board to determine the safety of other phthalates. Prior to this legislation, the Consumer Product Safety Commission had determined that voluntary withdrawals of DEHP and DINP from teethers, pacifiers, and rattles had eliminated the risk to children, and advised against enacting a phthalate ban.[36]

In another development in 1986, California voters approved an initiative to address their growing concerns about exposure to toxic chemicals. That initiative became the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, better known by its original name of Proposition 65.[37] In December 2013 DINP was listed as a chemical "known to the State of California to cause cancer"[38] This means that, starting December 2014, companies with 10 or more employees manufacturing, distributing or selling the product(s) containing diisononyl phthalate (DINP) are required to provide a clear and reasonable warning for that product. The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment, charged with maintaining the Proposition 65 list and enforcing its provisions, has implemented a "No Significant Risk Level" of 146 ug/day for DINP, as of 1 April 2016.

Identification in plastics

Phthalates are used in some but not all PVC formulations, and there are no specific labeling requirements for phthalates. PVC plastics are typically used for various containers and hard packaging, medical tubing, and bags, and are labelled "Type 3" for recycling reasons. However, the presence of phthalates rather than other plasticizers is not marked on PVC items. Only unplasticized PVC (uPVC), which is mainly used as a hard construction material, has no plasticizers. If a more accurate test is needed, chemical analysis, for example by gas chromatography or liquid chromatography, can establish the presence of phthalates.

Polyethylene terephthalate (PETE) is the main substance used to package bottled water and many sodas. Products containing PETE are labeled "Type 1" (with a "1" in the recycle triangle) for recycling purposes. Although the word "phthalate" appears in the name, PETE does not use phthalates as plasticizers. The terephthalate polymer PETE and the phthalate ester plasticizers are chemically different substances.[39] Despite this, however, a number of studies have found phthalates such as DEHP in bottled water and soda.[40] One hypothesis is that these may have been introduced during plastics recycling.[40] Several studies tested the liquids before they were bottled, to make sure the phthalates came from the bottles rather than already being in the water.

Detection in food products

In February 2009, the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission published a review of methods to measure phthalates in food.[41]

See also

- Xenoestrogen

- Non-phthalate plasticizers such as

- Antiandrogens in the environment

References

- ↑ "ACC Addresses Phthalates Safety" on YouTube: video of Steve Risotto of the American Chemistry Council, uploaded by user AmericanChemistry on 23 Oct 2009, retrieved 23 Dec 2011.

- ↑ "phthalate, n.". oed.com.

- 1 2 L 44, 18.2.2011 Regulation (EU) No 143/2011 of 17 February 2011 amending Annex XIV to Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (‘REACH’)

- ↑ "Phthalates | Assessing and Managing Chemicals Under TSCA". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ↑ Ceresana. "Plasticizers – Study: Market, Analysis, Trends - Ceresana". ceresana.com.

- 1 2 Bertelsen, Randi J.; Carlsen, Karin C. Lødrup; Calafat, Antonia M.; Hoppin, Jane A.; Håland, Geir; Mowinckel, Petter; Carlsen, Kai-Håkon; Løvik, Martinus (2013-02-01). "Urinary biomarkers for phthalates associated with asthma in Norwegian children". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (2): 251–256. ISSN 1552-9924. PMC 3569683

. PMID 23164678. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205256.

. PMID 23164678. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205256. - ↑ E., Wilkes, C.; W., Summers, J.; A., Daniels, C.; T., Berard, Mark (2005-01-01). PVC handbook. Hanser. ISBN 3446227148. OCLC 488962111.

- 1 2 Pthalates Fact Sheet (PDF) (Report). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 2009.

- ↑ Serrano, Samantha E.; Braun, Joseph; Trasande, Leonardo; Dills, Russell; Sathyanarayana, Sheela (2014-06-02). "Phthalates and diet: a review of the food monitoring and epidemiology data". Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source. 13 (1): 43. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 4050989

. PMID 24894065. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-13-43.

. PMID 24894065. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-13-43. - 1 2 Third National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, (PDF) U.S. CDC, July 2005. Archived April 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Rudel R, Perovich L (January 2008). "Endocrine disrupting chemicals in indoor and outdoor air". Atmospheric Environment. 43 (1): 170–81. PMC 2677823

. PMID 20047015. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.025.

. PMID 20047015. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.09.025. - ↑ CEH: Plasticizers (Report). IHS Markit. July 2015. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ↑ https://echa.europa.eu/information-on-chemicals/cl-inventory-database/-/discli/details/10536

- ↑ "Bio-based plasticizer". University of Minnesota.

- ↑ Carlstedt, F.; Jönsson, B. a. G.; Bornehag, C.-G. (2013-02-01). "PVC flooring is related to human uptake of phthalates in infants". Indoor Air. 23 (1): 32–39. ISSN 1600-0668. PMID 22563949. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0668.2012.00788.x.

- ↑ Erythropel, Hanno C.; Maric, Milan; Nicell, Jim A.; Leask, Richard L.; Yargeau, Viviane (2014-12-01). "Leaching of the plasticizer di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) from plastic containers and the question of human exposure". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 98 (24): 9967–9981. ISSN 1432-0614. PMID 25376446. doi:10.1007/s00253-014-6183-8.

- 1 2 Heudorf U, Mersch-Sundermann V, Angerer J (October 2007). "Phthalates: toxicology and exposure". Int J Hyg Environ Health. 210 (5): 623–34. PMID 17889607. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.07.011.

- ↑ Zota, Ami R.; Phillips, Cassandra A.; Mitro, Susanna D. (2016-10-01). "Recent Fast Food Consumption and Bisphenol A and Phthalates Exposures among the U.S. Population in NHANES, 2003-2010". Environmental Health Perspectives. 124 (10): 1521–1528. ISSN 1552-9924. PMC 5047792

. PMID 27072648. doi:10.1289/ehp.1510803.

. PMID 27072648. doi:10.1289/ehp.1510803. - 1 2 3 Kolarik B, Bornehag C, Naydenov K, Sundell J, Stavova P, Nielsen O (December 2008). "The concentration of phthalates in settled dust in Bulgarian homes in relation to building characteristic and cleaning habits in the family". Atmospheric Environment. 42 (37): 8553–9. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.08.028.

- ↑ Sathyanarayana S, Karr CJ, Lozano P, et al. (February 2008). "Baby care products: possible sources of infant phthalate exposure". Pediatrics. 121 (2): e260–8. PMID 18245401. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-3766.

- 1 2 Sathyanarayana S (2008). "Phthalates and children's health". Current Problems In Adolescent Health Care. 38: 34–39. doi:10.1016/j.cppeds.2007.11.001.

- ↑ Opinion on phthalates in school supplies (PDF) (Report). Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks, European Commission. 17 October 2008.

- 1 2 3 Hernández-Díaz S, Mitchell AA, Kelley KE, Calafat AM, Hauser R (February 2009). "Medications as a Potential Source of Exposure to Phthalates in the U.S. Population". Environ. Health Perspect. 117 (2): 185–9. PMC 2649218

. PMID 19270786. doi:10.1289/ehp.11766.

. PMID 19270786. doi:10.1289/ehp.11766.

- ↑ Phthalates and Cumulative Risk Assessment: The Tasks Ahead. National Research Council. 2008-12-18. ISBN 9780309128414. doi:10.17226/12528

.

. - 1 2 Albert, O.; Jegou, B. (2013). "A critical assessment of the endocrine susceptibility of the human testis to phthalates from fetal life to adulthood". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 231–49. PMID 24077978. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt050.

- ↑ Waring, R. H.; Harris, R. M. (2011-02-01). "Endocrine disrupters--a threat to women's health?". Maturitas. 68 (2): 111–115. ISSN 1873-4111. PMID 21075568. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.10.008.

- ↑ Toppari J, Virtanen H, Skakkebaek NE, Main KM (2006). "Environmental effects on hormonal regulation of testicular descent". J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 102 (1–5): 184–6. PMID 17049842. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.020.

- ↑ McPartland, John M.; Guy, Geoffrey W.; Di Marzo, Vincenzo (2014-03-12). "Care and Feeding of the Endocannabinoid System: A Systematic Review of Potential Clinical Interventions that Upregulate the Endocannabinoid System". PLoS ONE. 9 (3): e89566. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3951193

. PMID 24622769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089566.

. PMID 24622769. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089566. - 1 2 3 4 5 Desvergne B, Feige J, Casals-Casas C (2009). "PPAR-mediated activity of phthalates: A link to the obesity epidemic?". Mol Cell Endocrinol. 304 (1–2): 43–8. PMID 19433246. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.017.

- ↑ "Chronic Hazard Advisory on Diisononyl Phthalate" (PDF). 2001. p. 87. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

Human risk is therefore seen as negligible

- ↑ "Commission Decision of 7 December 1999 adopting measures prohibiting the placing on the market of toys and childcare articles intended to be placed in the mouth by children under three years of age made of soft PVC containing one or more of the substances di-iso-nonyl phthalate (DINP), di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), di-iso-decyl phthalate (DIDP), di-n-octyl phthalate (DNOP), and butylbenzyl phthalate (BBP)".

- ↑ https://chemicalwatch.com/23104/echa-and-denmark-to-prepare-phthalates-restriction

- ↑ http://echa.europa.eu/registry-of-current-restriction-proposal-intentions/-/substance-rev/6301/term

- ↑ Ms. KFT Retrieved 22 December 2014

- ↑ GovTrack.us. "H.R. 4040--110th Congress (2007): Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008, GovTrack.us (database of federal legislation) . Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- ↑ Public Concern, Not Science, Prompts Plastics Ban by Jon Hamilton, NPR.

- ↑ "OEHHA Proposition 65: Proposition 65 in Plain Language!". ca.gov.

- ↑ "OEHHA Proposition 65 (2013) Diisononyl Phthalate (DINP) listed". ca.gov.

- ↑ "Learn the Facts About Food Packaging and Phthalates". Plasticsmythbuster.org. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- 1 2 Sax, Leonard (2010-04-01). "Polyethylene Terephthalate May Yield Endocrine Disruptors". Environmental Health Perspectives. 118 (4): 445–448. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 2854718

. PMID 20368129. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901253.

. PMID 20368129. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901253. - ↑ Methods for the determination of phthalates in food, (PDF) European Commission, Joint Research Centre Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Lovekamp-Swan T, Davis BJ (February 2003). "Mechanisms of phthalate ester toxicity in the female reproductive system". Environ. Health Perspect. 111 (2): 139–45. PMC 1241340

. PMID 12573895. doi:10.1289/ehp.5658.

. PMID 12573895. doi:10.1289/ehp.5658. - Tickner JA, Schettler T, Guidotti T, McCally M, Rossi M (January 2001). "Health risks posed by use of Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) in PVC medical devices: a critical review". Am. J. Ind. Med. 39 (1): 100–11. PMID 11148020. doi:10.1002/1097-0274(200101)39:1<100::AID-AJIM10>3.0.CO;2-Q.

- Kohn MC, Parham F, Masten SA, et al. (October 2000). "Human exposure estimates for phthalates". Environ. Health Perspect. 108 (10): A440–2. JSTOR 3435033. PMC 1240144

. PMID 11097556. doi:10.2307/3435033.

. PMID 11097556. doi:10.2307/3435033. - Centers for Disease Control. "National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Updated Tables, February 2011". Archived from the original on November 29, 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control. "Phthalate Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on December 29, 2010.

- Centers for Disease Control. "Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry-Public Health Statement for Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate DEHP".

- Latini, G.; Del Vecchio, A.; et al. (2006). "Phthalate Exposure and Male Infertility". Toxicology. 226 (2–3): 90–98. PMID 16905236. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2006.07.011.

- Mendes, Amaral J. (2002). "The endocrine disruptors: a major medical challenge". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 40 (6): 781–788. PMID 11983272. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00018-2.