Phospholipase C

Phospholipase C (PLC) is a class of membrane-associated enzymes that cleave phospholipids just before the phosphate group (see figure). It is most commonly taken to be synonymous with the human forms of this enzyme, which play an important role in eukaryotic cell physiology, in particular signal transduction pathways. There are thirteen kinds of mammalian phospholipase C that are classified into six isotypes (β, γ, δ, ε, ζ, η) according to structure. Each PLC has unique and overlapping controls over expression and subcellular distribution. Activators of each PLC vary, but typically include heterotrimeric G protein subunits, protein tyrosine kinases, small G proteins, Ca2+, and phospholipids.[1]

Variants

Mammalian variants

The extensive number of functions exerted by the PLC reaction requires that it be strictly regulated and able to respond to multiple extra- and intracellular inputs with appropriate kinetics. This need has guided the evolution of six isotypes of PLC in animals, each with a distinct mode of regulation. The pre-mRNA of PLC can also be subject to differential splicing such that a mammal may have up to 30 PLC enzymes.[2]

- beta: PLCB1, PLCB2, PLCB3, PLCB4

- gamma: PLCG1, PLCG2

- delta: PLCD1, PLCD3, PLCD4

- epsilon: PLCE1

- eta: PLCH1, PLCH2

- zeta: PLCZ1

- phospholipase C-like: PLCL1, PLCL2

Bacterial variants

Most of the bacterial variants of phospholipase C are characterized into one of four groups of structurally related proteins. The toxic phospholipases C are capable of interacting with eukaryotic cell membranes and hydrolyzing phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, ultimately leading to cell lysis.[3]

- Zinc-metallophospholipases C: Clostridium perfringens alpha-toxin, Bacillus cereus PLC (BC-PLC)

- Sphingomyelinases: B. cereus, Staphylococcus aureus

- Phosphatidylinositol-hydrolyzing enzymes: B. cereus, B. thuringiensis, L. monocytogenes (PLC-A)

- Pseudomonad phospholipases C: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PLC-H and PLC-N)

Enzyme structure

In mammals, PLCs share a conserved core structure and differ in other domains specific for each family. The core enzyme includes a split triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) barrel, pleckstrin homology (PH) domain, four tandem EF hand domains, and a C2 domain.[1] The TIM barrel contains the active site, all catalytic residues, and a Ca2+ binding site. It has an autoinhibitory insert that interrupts its activity called an X-Y linker. The X-Y linker has been shown to occlude the active site, and with its removal PLC is activated.[4]

The genes encoding alpha-toxin (Clostridium perfringens), Bacillus cereus PLC (BC-PLC), and PLCs from Clostridium bifermentans and Listeria monocytogenes have been isolated and nucleotides sequenced. There is significant homology of the sequences, approximately 250 residues, from the N-terminus. Alpha-toxin has an additional 120 residues in the C-terminus. The C-terminus of the alpha-toxin has been reported as a “C2-like” domain, referencing the C2 domain found in eukaryotes that are involved in signal transduction and present in mammalian phosphoinositide phospholipase C.[5]

Enzyme mechanism

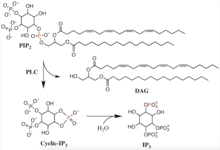

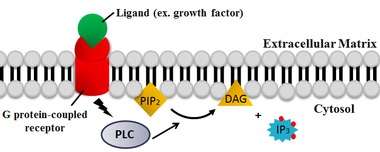

The primary catalyzed reaction of PLC occurs on an insoluble substrate at a lipid-water interface. The residues in the active site are conserved in all PLC isotypes. In animals, PLC selectively catalyzes the hydrolysis of the phospholipid, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), on the glycerol side of the phosphodiester bond. There is the formation of a weakly enzyme-bound intermediate, inositol 1,2-cyclic phosphodiester, and release of diacyl glycerol (DAG). The intermediate is then hydrolyzed to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3).[6] Thus the two end products are DAG and IP3. The acid/base catalysis requires two conserved histidine residues and a Ca2+ ion is needed for PIP2 hydrolysis. It has been observed that the active-site Ca2+ coordinates with four acidic residues and if any of the residues are mutated then a greater Ca2+ concentration is needed for catalysis.[7]

Regulation

Activation

Receptors that activate this pathway are mainly G protein-coupled receptors coupled to the Gαq subunit, including:

- 5-HT2 serotonergic receptors

- α1 (Alpha-1) adrenergic receptors[8]

- Calcitonin receptors

- H1 histamine receptors

- Metabotropic glutamate receptors, Group I

- M1, M3, and M5 muscarinic receptors

- Thyroid-Releasing Hormone receptor in anterior pituitary gland

Other, minor, activators than Gαq are:

- MAP kinase. Activators of this pathway include PDGF and FGF.[8]

- βγ-complex of heterotrimeric G-proteins, as in a minor pathway of growth hormone release by growth hormone-releasing hormone.[9]

- Cannabinoid receptors

Inhibition

- Small molecule U73122: aminosteroid, putative PLC inhibitor.[10][11] However, the specificity of U73122 has been questioned.[12] It has been reported that U73122 activates the phospholipase activity of purified PLCs.[13]

- Edelfosine: lipid-like, anti-neoplastic agent (ET-18-OCH3)[14]

- Autoinhibition of X-Y linker in mammalian cells: It is proposed that the X-Y linker consists of long stretches of acidic amino acids that form dense areas of negative charge. These areas could be repelled by the negatively charged membrane upon binding of the PLC to membrane lipids. The combination of repulsion and steric constraints is thought to remove the X-Y linker from near the active site and relieve auto-inhibition.[1]

- o-phenanthroline: heterocyclic organic compound, known to inhibit zinc-metalloenzymes[15]

- EDTA: molecule that chelates Zn2+ ions and effectively inactivates PLC, known to inhibit zinc-metalloenzymes[16]

Biological function

PLC cleaves the phospholipid phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) into diacyl glycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). Thus PLC has a profound impact on the depletion of PIP2, which acts as a membrane anchor or allosteric regulator.[17] PIP2 also acts as the substrate for synthesis of the rarer lipid phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3), which is responsible for signaling in multiple reactions.[18] Therefore, PIP2 depletion by the PLC reaction is critical to the regulation of local PIP2 concentrations both in the plasma membrane and the nuclear membrane.

The two products of the PLC catalyzed reaction, DAG and IP3, are important second messengers that control diverse cellular processes and are substrates for synthesis of other important signaling molecules. When PIP2 is cleaved, DAG remains bound to the membrane, and IP3 is released as a soluble structure into the cytosol. IP3 then diffuses through the cytosol to bind to IP3 receptors, particularly calcium channels in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This causes the cytosolic concentration of calcium to increase, causing a cascade of intracellular changes and activity.[19] In addition, calcium and DAG together work to activate protein kinase C, which goes on to phosphorylate other molecules, leading to altered cellular activity.[19] End-effects include taste, tumor promotion, as well as vesicle exocytosis, superoxide production from NADPH oxidase, and JNK activation.[19][20]

Both DAG and IP3 are substrates for the synthesis of regulatory molecules. DAG is the substrate for the synthesis of phosphatidic acid, a regulatory molecule. IP3 is the rate-limiting substrate for the synthesis of inositol polyphosphates, which stimulate multiple protein kinases, transcription, and mRNA processing.[21] Regulation of PLC activity is thus vital to the coordination and regulation of other enzymes of pathways that are central to the control of cellular physiology.

Additionally, phospholipase C plays an important role in the inflammation pathway. The binding of agonists such as thrombin, epinephrine, or collagen, to platelet surface receptors can trigger the activation of phospholipase C to catalyze the release of arachidonic acid from two major membrane phospholipids, phosphatidylinositol and phosphatidylcholine. Arachidonic acid can then go on into the cyclooxygenase pathway (producing prostoglandins (PGE1, PGE2, PGF2), prostacyclins (PGI2), or thromboxanes (TXA2)), and the lipoxygenase pathway (producing leukotrienes (LTB4, LTC4, LTD4, LTE4)).[22]

The bacterial variant Clostridium perfringens type A produces alpha-toxin. The toxin has phospholipase C activity, and causes hemolysis, lethality, and dermonecrosis. At high concentrations, alpha-toxin induces massive degradation of phosphatidylcholine and sphingomyelin, producing diacylglycerol and ceramide, respectively. These molecules then participate in signal transduction pathways.[5] It has been reported that the toxin activates the arachidonic acid cascade in isolated rat aorta.[23] The toxin-induced contraction was related to generation of thromboxane A2 from arachidonic acid. Thus it is likely the bacterial PLC mimics the actions of endogenous PLC in eukaryotic cell membranes.

See also

- Glycosylphosphatidylinositol diacylglycerol-lyase EC 4.6.1.14 A trypanosomal enzyme.

- Phosphatidylinositol diacylglycerol-lyase EC 4.6.1.13 Another related bacterial enzyme

- Phosphoinositide phospholipase C EC 3.1.4.11 The main form found in eukaryotes, especially mammals.

- Zinc-dependent phospholipase C family of bacterial enzymes EC 3.1.4.3 that includes the alpha toxins of C. perfringens (also known as lecithinase), P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus.

References

- 1 2 3 Kadamur, Ganesh; Ross, Elliot M. (2013). "Mammalian Phospholipase C". Annual Review of Physiology. 75: 127–154. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183750. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ Suh, PG; Park, JI; Manzoli, L; Cocco, L; Peak, JC; Katan, M; Fukami, K; Kataoka, T; Yun, S; Ryu, SH (2008). "Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes.". BMB Reports. 41 (6): 415–34. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.6.415.

- ↑ Titball, RW (1993). "Bacterial phospholipases C.". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (2): 347–66.

- ↑ Hicks, SN; Jezyk, MR; Gershburg, S; Seifert, JP; Harden, TK; Sondek, J (2008). "General and versatile autoinhibition of PLC isozymes.". Molecular Cell. 31 (3): 383–94. PMC 2702322

. PMID 18691970. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018.

. PMID 18691970. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.018. - 1 2 Sakurai, Jun; Nagahama, Masahiro; Oda, Masataka (2004). "Clostridium perfringens Alpha-Toxin: Characterization and Mode of Action". The Journal of Biochemistry. 136 (5): 569–74. PMID 15632295. doi:10.1093/jb/mvh161.

- ↑ Essen, LO; Perisic, O; Katan, M; Yiqin, W; Roberts, MF; Williams, RL (1997). "Structural Mapping of the Catalytic Mechanism for a Mammalian Phosphoinositide-Specific Phospholipase C". Biochemistry. 36 (7): 1704–18. PMID 9048554. doi:10.1021/bi962512p.

- ↑ Ellis, MV; James, SR; Perisic, O; Downes, PC; Williams, RL; Katan, M (1998). "Catalytic Domain of Phosphoinositide-specific Phospholipase C (PLC): mutation analysis of residues within the active site of hydrophobic ridge of PLCD1". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (19): 11650–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.19.11650.

- 1 2 Walter F. Boron (2003). Medical Physiology: A Cellular And Molecular Approaoch. Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1300. ISBN 1-4160-2328-3. Page 104

- ↑ GeneGlobe -> GHRH Signaling Retrieved on May 31, 2009

- ↑ Bleasdale, JE; Thakur, NR; Gremban, RS; Bundy, GL; Fitzpatrick, FA; Smith, RJ; Bunting, S (1990). "Selective inhibition of receptor-coupled phospholipase C-dependent processes in human platelets and polymorphonuclear neutrophils.". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 255 (2): 756–68. PMID 2147038.

- ↑ MacMillan, D; McCarron, JG (2010). "The phospholipase C inhibitor U-73122 inhibits Ca2+ release from the intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store by inhibiting Ca2+ pumps in smooth muscle". British Journal of Pharmacology. 160 (6): 1295–1301. PMC 2938802

. PMID 20590621. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00771.x.

. PMID 20590621. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00771.x. - ↑ Huang, W; Barrett, M; Hajicek, N; Hicks, S; Harden, TK; Sondek, J; Zhang, Q (2013). "Small Molecule Inhibitors of Phospholipase C from a Novel High-throughput Screen.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288: 5840–8. PMC 3581404

. PMID 23297405. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.422501.

. PMID 23297405. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.422501. - ↑ Klein, RR; Bourdon, DM; Costales, CL; Wagner, CD; White, WL; Hicks, SN; Sondek, J; Thakker, DR (2011). "Direct activation of human phospholipase C by its well known inhibitor U73122.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 286: 12407–16. PMC 3069444

. PMID 21266572. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.191783.

. PMID 21266572. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.191783. - ↑ Horowitz, LF; Hirdes, W; Suh, BC; Hilgemann, DW; Mackie, K; Hille, B (2005). "Phospholipase C in Living Cells: Activation, Inhibition, Ca2+ Requirement, and Regulation of M Current". J Gen Physiol. 126 (3): 243–62. PMC 2266577

. PMID 16129772. doi:10.1085/jgp.200509309.

. PMID 16129772. doi:10.1085/jgp.200509309. - ↑ Little, C; Otnass, AB (1975). "The metal ion dependence of phospholipase C from Bacillus cereus.". Biochim Biophys Acta. 391 (2): 326–33. PMID 807246. doi:10.1016/0005-2744(75)90256-9.

- ↑ "Phospholipase C, Phosphatidylinositol-specific from Bacillus cereus" (PDF). Product Information. Sigma Aldrich.

- ↑ Hilgemann, DW (2007). "Local PIP(2) signals: when, where, and how?". European Journal of Physiology. 455 (1): 55–67. PMID 17534652. doi:10.1007/s00424-007-0280-9.

- ↑ Falkenburger, BH; Jensen, JB; Dickson, EJ; Suh, BC; Hille, B (2010). "Phosphoinositides: lipid regulators of membrane proteins.". The Journal of Physiology. 588 (17): 3179–85. PMC 2976013

. PMID 20519312. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192153.

. PMID 20519312. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192153. - 1 2 3 Alberts B, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

- ↑ Li, Z; Jiang, H; Xie, W; Zhang, Z; Smrcka, A; Wu, D (2000). "Roles of PLC-β2 and -β3 and PI3Kγ in Chemoattractant-Mediated Signal Transduction". Science. 287 (5455): 1046–1049. PMID 10669417. doi:10.1126/science.287.5455.1046.

- ↑ Gresset, A; Sondek, J; Harden, TK (2012). "The phospholipase C isozymes and their regulation.". Subcellular Biochemistry. 58 (61): 61–94. PMC 3638883

. PMID 22403074. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_3.

. PMID 22403074. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-3012-0_3. - ↑ Piomelli, Daniele (1993-04-01). "Arachidonic acid in cell signaling". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 5 (2): 274–280. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(93)90116-8.

- ↑ Fujii, Y; Sakurai, J (1989). "Contraction of the rat isolated aorta caused by Clostridium perfringens alpha toxin (phospholipase C): evidence for the involvement of arachidonic acid metabolism". Br. J. Pharmacol. 97 (1): 119–24. PMC 1854495

. PMID 2497921. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11931.x.

. PMID 2497921. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11931.x.