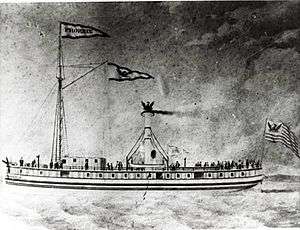

Phoenix (1845)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Phoenix |

| Owner: | Pease and Allen, Cleveland |

| Completed: | 1845 |

| Out of service: | 21 November 1847 |

| Fate: | Burned to the waterline, 21 November 1847 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Wooden steamship |

| Displacement: | 302 |

| Length: | 140 feet (43 m) |

| Beam: | 22 feet (6.7 m) |

| Depth: | 10 feet (3.0 m) |

| Propulsion: | Steam-powered propellers |

| Crew: | 25 |

The Phoenix was a steamship that burned on Lake Michigan on 21 November 1847, with the loss of at least 190 but perhaps as many as 250 lives. The loss of life made this disaster, in terms of loss of life from the sinking of a single vessel, the fourth-worst tragedy in the history of the Great Lakes.[1]

Characteristics

The Phoenix was built in 1845 in Cleveland, Ohio[2][3] or Buffalo, New York.[4]:47 It was built with the then-new technology of twin screw propellers instead of side-mounted paddlewheels. The ship was 140 feet (43 m) long, with a beam of 22 feet (6.7 m), a depth of 10 feet (3.0 m) and a displacement of 302 tons.[4]:47

Career

The Phoenix spent its career making trips between Buffalo and Chicago.[5]:53 The ship was owned by Pease and Allen of Cleveland.[6]:282

Final voyage

The Phoenix departed Buffalo on 11 November 1847, for its last trip of the year. It was carrying around 275 passengers, mostly Dutch immigrants, and a crew of 25 commanded by Captain G. B. Sweet. The ship also carried a cargo of molasses, coffee, sugar, and hardware.[7] While on Lake Erie Captain Sweet fell and injured his knee badly enough that he was forced to stay in bed for the rest of the journey. The first mate, H. Watts, took command.[4]:48[5]:54

The Phoenix reached Manitowoc, Wisconsin just before midnight on 20 November. The ship took on cordwood for fuel and unloaded cargo while waiting for the weather to improve.[4]:48[5]:55 The Phoenix departed Manitowoc at 1 am on 21 November.[4]:48[6]:283[8]

About two hours out of Manitowoc, the fireman tending the Phoenix's boilers noticed that the pumps were not working properly. He reported this to the ship's second engineer, but was ignored; he later reported that the water in the boilers was dangerously low, but was again ignored.[7]:100

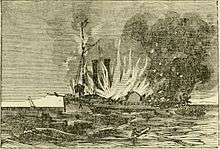

At 4 am, clouds of smoke started billowing from the ship's engine room.[5]:56[7]:100 The ship's passengers were alerted, and the first mate organized the crew and passengers into a bucket brigade in an attempt to fight the fire. The fire soon grew out of control.[5]:56[8] First Mate Watts ordered the ship turned towards shore, but the fire overwhelmed the engine room and the ship drifted to a halt about five miles from shore and nine miles from Sheboygan.[4]:49

The Phoenix carried only two lifeboats, with a capacity of 20 people each. These were quickly launched: the first with Captain Sweet and 20 others, the second carrying 19. By the time the lifeboats reached the shore, those aboard were exhausted from rowing, and unable to return to try and rescue more people.[7]:102

Meanwhile, the Phoenix was being consumed by flames. The crew and passengers tore apart the cabin and threw the pieces overboard to use as floats. The water was freezing cold; most of those who managed to find wreckage to cling to succumbed to hypothermia.[6]:284 Those who remained on the ship tried to climb upward to rigging, but the rigging burned and collapsed, sending those on it into the fire below.[4]:49

In the nearby town of Sheboygan, a justice of the peace named Judge Morris woke and spotted the flames on the lake. He ran down to the harbor and woke the crew of the steamer Delaware, who began building up the steam needed to take their ship out to assist. At around the same time the captain of the schooner Liberty saw the flames, and he and his crew manned the ship's lifeboat and rowed for the Phoenix.[4]:50

By the time the Delaware arrived at around 7 am, the Phoenix had burned to the waterline. The Delaware found only three survivors: the ship's clerk and a passenger clinging to the rudder chains, and an engineer clinging to a door. The boat from the Liberty arrived soon after, followed by one of the Phoenix's lifeboats.[6]:286 The Delaware retrieved five bodies from the water, then took the hull of the Phoenix and the Liberty's lifeboat in tow.[4]:51 The Delaware towed the wreck to Sheboygan, where it was beached by the city's north pier.[7]:103

Aftermath

The exact death toll from the Phoenix is not known. The owners of the ship claimed that no more than 190 died, but the ship's clerk estimated that the number of lives lost was at least 250. 43 people were saved; 40 in the lifeboats and three rescued by the Delaware.[4]:51

The engine, boiler, and cargo were later salvaged from the hulk of the Phoenix.[9]

The Delaware would later come across the scene of another Great Lakes disaster. On 17 June 1850 when the G. P. Griffith burned with a loss of at least 241 of the roughly 300 people aboard, the Delaware arrived on the scene. Too late to rescue survivors, the Delaware could do no more than tow the burning wreck to shore, just as it did with the Phoenix. The Delaware itself sank on 3 November 1855 with the loss of 11 lives.[6]:291–292

References

- ↑ Ratigan, Willaim (1977). Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals: Str. Edmund Fitzgerald edition. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 68–69.

- ↑ "New Vessels Built in 1845". Buffalo Commercial Advertiser. 10 January 1846. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Orth, Samuel Peter (1910). A History of Cleveland, Ohio, Volume 1. Cleveland, OH: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 712. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Shelak, Benjamin J. (2003). Shipwrecks of Lake Michigan. Black Earth, WI: Trails Books. pp. 47–52. ISBN 1-931599-21-1. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ratigan, William (1973). Great Lakes shipwrecks & survivals (2nd ed.). Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. pp. 53–60. ISBN 0-8028-7010-4. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Van Eyck, William O (March 1924). "The Story of the Propeller Phoenix". The Wisconsin Magazine of History. Wisconsin Historical Society. 7 (3): 281–300. JSTOR 4630497.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thompson, Mark L. (2004). Graveyard of the Lakes. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 99–103. ISBN 0-8143-3226-9. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- 1 2 Bruce, William George, ed. (1922). History of Milwaukee, City and County, Volume 1. Milwaukee: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. pp. 144–145. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ "The engine, boiler and all the cargo". Buffalo Commercial Advertiser. 29 June 1848. Retrieved 12 February 2016.