Philosophical Investigations

Cover of the first English edition | |

| Author | Ludwig Wittgenstein |

|---|---|

| Original title | Philosophische Untersuchungen |

| Translator | G. E. M. Anscombe |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Ordinary language philosophy |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| OCLC | 954131267 |

Philosophical Investigations (German: Philosophische Untersuchungen) is a work by the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, first published, posthumously, in 1953, in which Wittgenstein discusses numerous problems and puzzles in the fields of semantics, logic, philosophy of mathematics, philosophy of psychology, philosophy of action, and philosophy of mind. He puts forth the view that conceptual confusions surrounding language use are at the root of most philosophical problems, contradicting or discarding much of what he argued in his earlier work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921).

He alleges that the problems are traceable to a set of related assumptions about the nature of language, which themselves presuppose a particular conception of the essence of language. This conception is considered and ultimately rejected for being too general; that is, as an essentialist account of the nature of language it is simply too narrow to be able to account for the variety of things we do with language. Wittgenstein begins the book with a quotation from St. Augustine, whom he cites as a proponent of the generalized and limited conception that he then summarizes:

The individual words in language name objects—sentences are combinations of such names. In this picture of language we find the roots of the following idea: Every word has a meaning. This meaning is correlated with the word. It is the object for which the word stands.

He then sets out throughout the rest of the book to demonstrate the limitations of this conception, including, he argues, with many traditional philosophical puzzles and confusions that arise as a result of this limited picture. Philosophical Investigations is highly influential. Within the analytic tradition, the book is considered by many as being one of the most important philosophical works of the 20th century, and it continues to influence contemporary philosophers, especially those studying mind and language.[1]

The text

Editions and referencing

Philosophical Investigations was not ready for publication when Wittgenstein died in 1951. G. E. M. Anscombe translated Wittgenstein's manuscript into English, and it was first published in 1953. There are multiple editions of Philosophical Investigations with the popular third edition and 50th anniversary edition having been edited by Anscombe:

- First Edition: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1953.

- Second Edition: Blackwell Publishers, 1958.

- Third Edition: Prentice Hall, 1973 (ISBN 0-02-428810-1).

- 50th Anniversary Edition: Blackwell Publishers, 2001 (ISBN 0-631-23127-7). This edition includes the original German text in addition to the English translation.[2]

- Fourth Edition: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009 (ISBN 1405159286).

The text is divided into two parts, consisting of what Wittgenstein calls, in the preface, Bemerkungen, translated by Anscombe as "remarks".[3] In the first part, these remarks are rarely more than a paragraph long and are numbered sequentially. In the second part, the remarks are longer and numbered using Roman numerals. In the index, remarks from the first part are referenced by their number rather than page; however, references from the second part are cited by page number. The comparatively unusual nature of the second part is due to the fact that it comprises notes that Wittgenstein may have intended to re-incorporate into the first part. Subsequent to his death it was published as a "Part II" in the first, second and third editions. However, in light of continuing uncertainty about Wittgenstein's intentions regarding this material, the fourth edition (2009) re-titles "Part I" as "Philosophical Investigations" proper, and "Part II" as "Philosophy of Psychology – A Fragment."

In standard references, a small letter following a page, section, or proposition number indicates a paragraph.[4]

Method and presentation

Philosophical Investigations is unique in its approach to philosophy. A typical philosophical text presents a philosophical problem, summarizes and critiques various alternative approaches to solving it, presents its own approach, and then argues in favour of that approach. In contrast, Wittgenstein's book treats philosophy as an activity, rather along the lines of Socrates's famous method of maieutics; he has the reader work through various problems, participating actively in the investigation. Rather than presenting a philosophical problem and its solution, Wittgenstein engages in a dialogue, where he provides a thought experiment (a hypothetical example or situation), describes how one might be inclined to think about it, and then shows why that inclination suffers from conceptual confusion. The following is an excerpt from the first entry in the book that exemplifies this method:

...think of the following use of language: I send someone shopping. I give him a slip marked 'five red apples'. He takes the slip to the shopkeeper, who opens the drawer marked 'apples', then he looks up the word 'red' in a table and finds a colour sample opposite it; then he says the series of cardinal numbers—I assume that he knows them by heart—up to the word 'five' and for each number he takes an apple of the same colour as the sample out of the drawer.—It is in this and similar ways that one operates with words—"But how does he know where and how he is to look up the word 'red' and what he is to do with the word 'five'?" Well, I assume that he acts as I have described. Explanations come to an end somewhere.—But what is the meaning of the word 'five'? No such thing was in question here, only how the word 'five' is used.[5]

This example is typical of the book's style. We can see each of the steps in Wittgenstein's method:

- The reader is presented with a thought experiment: someone is sent shopping with an order on a slip.

- Wittgenstein supplies the response of an imagined interlocutor. He usually puts these statements in quotes to distinguish them from his own: "But how does he know where and how he is to look up the word 'red' and what he is to do with the word 'five'?" Or Wittgenstein may indicate such a response by beginning with a long dash, as he does before the question above: —But what is the meaning of the word 'five'?

- Wittgenstein shows why the reader's reaction was misguided: No such thing was in question here, only how the word 'five' is used.

Similarly, Wittgenstein often uses the device of framing many of the remarks as a dialogue between himself and a disputant. For example, Remark 258 proposes a thought experiment in which a certain sensation is associated with the sign S written in a calendar. He then sets up a dialogue in which the disputant offers a series of ways of defining S, and he meets each with a suitable objection, so drawing the conclusion that in such a case there is no right definition of S.

Through such thought experiments, Wittgenstein attempts to get the reader to come to certain difficult philosophical conclusions independently; he does not simply argue in favor of his own theories.

Language, meaning, and use

The Investigations deals largely with the difficulties of language and meaning. Wittgenstein viewed the tools of language as being fundamentally simple,[6] and he believed that philosophers had obscured this simplicity by misusing language and by asking meaningless questions. He attempted in the Investigations to make things clear: "Der Fliege den Ausweg aus dem Fliegenglas zeigen"—to show the fly the way out of the fly bottle.[7]

Meaning is use

A common summary of his argument is that meaning is use—words are not defined by reference to the objects they designate, nor by the mental representations one might associate with them, but by how they are used. For example, this means there is no need to postulate that there is something called good that exists independently of any good deed.[8] This anthropological perspective contrasts with Platonic realism and with Gottlob Frege's notions of sense and reference.[9] This argument has been labeled by some authors as "anthropological holism."[10]

Meaning and definition

Wittgenstein rejects a variety of ways of thinking about what the meaning of a word is, or how meanings can be identified. He shows how, in each case, the meaning of the word presupposes our ability to use it. He first asks the reader to perform a thought experiment: to come up with a definition of the word "game".[11] While this may at first seem a simple task, he then goes on to lead us through the problems with each of the possible definitions of the word "game". Any definition that focuses on amusement leaves us unsatisfied since the feelings experienced by a world class chess player are very different from those of a circle of children playing Duck Duck Goose. Any definition that focuses on competition will fail to explain the game of catch, or the game of solitaire. And a definition of the word "game" that focuses on rules will fall on similar difficulties.

The essential point of this exercise is often missed. Wittgenstein's point is not that it is impossible to define "game", but that we don't have a definition, and we don't need one, because even without the definition, we use the word successfully.[12] Everybody understands what we mean when we talk about playing a game, and we can even clearly identify and correct inaccurate uses of the word, all without reference to any definition that consists of necessary and sufficient conditions for the application of the concept of a game. The German word for "game", "Spiele/Spiel", has a different sense than in English; the meaning of "Spiele" also extends to the concept of "play" and "playing." This German sense of the word may help readers better understand Wittgenstein's context in the remarks regarding games.

Wittgenstein argues that definitions emerge from what he termed "forms of life", roughly the culture and society in which they are used. Wittgenstein stresses the social aspects of cognition; to see how language works for most cases, we have to see how it functions in a specific social situation. It is this emphasis on becoming attentive to the social backdrop against which language is rendered intelligible that explains Wittgenstein's elliptical comment that "If a lion could talk, we could not understand him." However, in proposing the thought experiment involving the fictional character, Robinson Crusoe, a captain shipwrecked on a desolate island with no other inhabitant, Wittgenstein shows that language is not in all cases a social phenomenon (although, they are for most cases); instead the criterion for a language is grounded in a set of interrelated normative activities: teaching, explanations, techniques and criteria of correctness. In short, it is essential that a language is shareable, but this does not imply that for a language to function that it is in fact already shared.[13]

Wittgenstein rejects the idea that ostensive definitions can provide us with the meaning of a word. For Wittgenstein, the thing that the word stands for does not give the meaning of the word. Wittgenstein argues for this making a series of moves to show that to understand an ostensive definition presupposes an understanding of the way the word being defined is used.[14] So, for instance, there is no difference between pointing to a piece of paper, to its colour, or to its shape; but understanding the difference is crucial to using the paper in an ostensive definition of a shape or of a colour.

Family resemblances

Why is it that we are sure a particular activity — e.g. Olympic target shooting — is a game while a similar activity — e.g. military sharp shooting — is not? Wittgenstein's explanation is tied up with an important analogy. How do we recognize that two people we know are related to one another? We may see similar height, weight, eye color, hair, nose, mouth, patterns of speech, social or political views, mannerisms, body structure, last names, etc. If we see enough matches we say we've noticed a family resemblance.[15] It is perhaps important to note that this is not always a conscious process — generally we don't catalog various similarities until we reach a certain threshold, we just intuitively see the resemblances. Wittgenstein suggests that the same is true of language. We are all familiar (i.e. socially) with enough things which are games and enough things which are not games that we can categorize new activities as either games or not.

This brings us back to Wittgenstein's reliance on indirect communication, and his reliance on thought-experiments. Some philosophical confusions come about because we aren't able to see family resemblances. We've made a mistake in understanding the vague and intuitive rules that language uses, and have thereby tied ourselves up in philosophical knots. He suggests that an attempt to untangle these knots requires more than simple deductive arguments pointing out the problems with some particular position. Instead, Wittgenstein's larger goal is to try to divert us from our philosophical problems long enough to become aware of our intuitive ability to see the family resemblances.

Language-games

Wittgenstein develops this discussion of games into the key notion of a language-game. Wittgenstein introduces the term using simple examples,[16] but intends it to be used for the many ways in which we use language.[17] The central component of language games is that they are uses of language, and language is used in multifarious ways. For example, in one language-game, a word might be used to stand for (or refer to) an object, but in another the same word might be used for giving orders, or for asking questions, and so on. The famous example is the meaning of the word "game". We speak of various kinds of games: board games, betting games, sports, "war games". These are all different uses of the word "games". Wittgenstein also gives the example of "Water!", which can be used as an exclamation, an order, a request, or as an answer to a question. The meaning of the word depends on the language-game within which it is being used. Another way Wittgenstein puts the point is that the word "water" has no meaning apart from its use within a language-game. One might use the word as an order to have someone else bring you a glass of water. But it can also be used to warn someone that the water has been poisoned. One might even use the word as code by members of a secret society.

Wittgenstein does not limit the application of his concept of language games to word-meaning. He also applies it to sentence-meaning. For example, the sentence "Moses did not exist" (§79) can mean various things. Wittgenstein argues that independently of use the sentence does not yet 'say' anything. It is 'meaningless' in the sense of not being significant for a particular purpose. It only acquires significance if we fix it within some context of use. Thus, it fails to say anything because the sentence as such does not yet determine some particular use. The sentence is only meaningful when it is used to say something. For instance, it can be used so as to say that no person or historical figure fits the set of descriptions attributed to the person that goes by the name of "Moses". But it can also mean that the leader of the Israelites was not called Moses. Or that there cannot have been anyone who accomplished all that the Bible relates of Moses, etc. What the sentence means thus depends on its context of use.

Rules

One general characteristic of games that Wittgenstein considers in detail is the way in which they consist in following rules. Rules constitute a family, rather than a class that can be explicitly defined.[18] As a consequence, it is not possible to provide a definitive account of what it is to follow a rule. Indeed, he argues that any course of action can be made out to accord with some particular rule, and that therefore a rule cannot be used to explain an action.[19] Rather, that one is following a rule or not is to be decided by looking to see if the actions conform to the expectations in the particular form of life in which one is involved. Following a rule is a social activity.

Private language

Wittgenstein also ponders the possibility of a language that talks about those things that are known only to the user, whose content is inherently private. The usual example is that of a language in which one names one's sensations and other subjective experiences, such that the meaning of the term is decided by the individual alone. For example, the individual names a particular sensation, on some occasion, 'S', and intends to use that word to refer to that sensation.[20] Such a language Wittgenstein calls a private language.

Wittgenstein presents several perspectives on the topic. One point he makes is that it is incoherent to talk of knowing that one is in some particular mental state.[21] Whereas others can learn of my pain, for example, I simply have my own pain; it follows that one does not know of one's own pain, one simply has a pain. For Wittgenstein, this is a grammatical point, part of the way in which the language-game involving the word "pain" is played.[22]

Although Wittgenstein certainly argues that the notion of private language is incoherent, because of the way in which the text is presented the exact nature of the argument is disputed. First, he argues that a private language is not really a language at all. This point is intimately connected with a variety of other themes in his later works, especially his investigations of "meaning". For Wittgenstein, there is no single, coherent "sample" or "object" that we can call "meaning". Rather, the supposition that there are such things is the source of many philosophical confusions. Meaning is a complicated phenomenon that is woven into the fabric of our lives. A good first approximation of Wittgenstein's point is that meaning is a social event; meaning happens between language users. As a consequence, it makes no sense to talk about a private language, with words that mean something in the absence of other users of the language.

Wittgenstein also argues that one couldn't possibly use the words of a private language.[23] He invites the reader to consider a case in which someone decides that each time she has a particular sensation she will place a sign S in a diary. Wittgenstein points out that in such a case one could have no criteria for the correctness of one's use of S. Again, several examples are considered. One is that perhaps using S involves mentally consulting a table of sensations, to check that one has associated S correctly; but in this case, how could the mental table be checked for its correctness? It is "[a]s if someone were to buy several copies of the morning paper to assure himself that what it said was true", as Wittgenstein puts it.[24] One common interpretation of the argument is that while one may have direct or privileged access to one's current mental states, there is no such infallible access to identifying previous mental states that one had in the past. That is, the only way to check to see if one has applied the symbol S correctly to a certain mental state is to introspect and determine whether the current sensation is identical to the sensation previously associated with S. And while identifying one's current mental state of remembering may be infallible, whether one remembered correctly is not infallible. Thus, for a language to be used at all it must have some public criterion of identity.

Often, what is widely regarded as a deep philosophical problem will vanish, argues Wittgenstein, and eventually be seen as a confusion about the significance of the words that philosophers use to frame such problems and questions. It is only in this way that it is interesting to talk about something like a "private language" — i.e., it is helpful to see how the "problem" results from a misunderstanding.

To sum up: Wittgenstein asserts that, if something is a language, it cannot be (logically) private; and if something is private, it is not (and cannot be) a language.

Wittgenstein's beetle

Another point that Wittgenstein makes against the possibility of a private language involves the beetle-in-a-box thought experiment.[25] He asks the reader to imagine that each person has a box, inside of which is something that everyone intends to refer to with the word "beetle". Further, suppose that no one can look inside another's box, and each claims to know what a "beetle" is only by examining their own box. Wittgenstein suggests that, in such a situation, the word "beetle" could not be the name of a thing, because supposing that each person has something completely different in their boxes (or nothing at all) does not change the meaning of the word; the beetle as a private object "drops out of consideration as irrelevant".[25] Thus, Wittgenstein argues, if we can talk about something, then it is not private, in the sense considered. And, contrapositively, if we consider something to be indeed private, it follows that we cannot talk about it.

Kripke's account

The discussion of private languages was revitalized in 1982 with the publication of Saul Kripke's book Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language.[26] In this work, Kripke uses Wittgenstein's text to develop a particular type of skepticism about rules that stresses the communal nature of language-use as grounding meaning.[27] Kripke's version of Wittgenstein, although philosophically interesting, has been facetiously called Kripkenstein, with some scholars such as Gordon Baker, Peter Hacker, Colin McGinn, and John McDowell seeing it as a radical misinterpretation of Wittgenstein's text.

Mind

Wittgenstein's investigations of language lead to several issues concerning the mind. His key target of criticism is any form of extreme mentalism that posits mental states that are entirely unconnected to the subject's environment. For Wittgenstein, thought is inevitably tied to language, which is inherently social; therefore, there is no 'inner' space in which thoughts can occur. Part of Wittgenstein's credo is captured in the following proclamation: "An 'inner process' stands in need of outward criteria."[28] This follows primarily from his conclusions about private languages: similarly, a private mental state (a sensation of pain, for example) cannot be adequately discussed without public criteria for identifying it.

According to Wittgenstein, those who insist that consciousness (or any other apparently subjective mental state) is conceptually unconnected to the external world are mistaken. Wittgenstein explicitly criticizes so-called conceivability arguments: "Could one imagine a stone's having consciousness? And if anyone can do so—why should that not merely prove that such image-mongery is of no interest to us?"[29] He considers and rejects the following reply as well:

"But if I suppose that someone is in pain, then I am simply supposing that he has just the same as I have so often had." — That gets us no further. It is as if I were to say: "You surely know what 'It is 5 o'clock here' means; so you also know what 'It's 5 o'clock on the sun' means. It means simply that it is just the same there as it is here when it is 5 o'clock." — The explanation by means of identity does not work here.[30]

Thus, according to Wittgenstein, mental states are intimately connected to a subject's environment, especially their linguistic environment, and conceivability or imaginability. Arguments that claim otherwise are misguided. Wittgenstein has also said that "language is inherent and transcendental", which is also not difficult to understand, since we can only comprehend and explain transcendental affairs through language.

Wittgenstein and behaviorism

From his remarks on the importance of public, observable behavior (as opposed to private experiences), it may seem that Wittgenstein is simply a behaviorist—one who thinks that mental states are nothing over and above certain behavior. However, Wittgenstein resists such a characterization; he writes (considering what an objector might say):

"Are you not really a behaviourist in disguise? Aren't you at bottom really saying that everything except human behaviour is a fiction?" — If I do speak of a fiction, then it is of a grammatical fiction.[31]

Clearly, Wittgenstein did not want to be a behaviorist, nor did he want to be a cognitivist or a phenomenologist. He is, of course, primarily concerned with facts of linguistic usage. However, some argue that Wittgenstein is basically a behaviorist because he considers facts about language use as all there is. Such a claim is controversial, since it is not explicitly endorsed in the Investigations.

Seeing that vs. seeing as

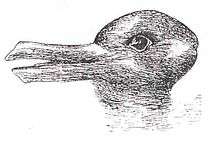

In addition to ambiguous sentences, Wittgenstein discussed figures that can be seen and understood in two different ways. Often one can see something in a straightforward way — seeing that it is a rabbit, perhaps. But, at other times, one notices a particular aspect — seeing it as something.

An example Wittgenstein uses is the "duckrabbit", an ambiguous image that can be seen as either a duck or a rabbit.[32] When one looks at the duck-rabbit and sees a rabbit, one is not interpreting the picture as a rabbit, but rather reporting what one sees. One just sees the picture as a rabbit. But what occurs when one sees it first as a duck, then as a rabbit? As the gnomic remarks in the Investigations indicate, Wittgenstein isn't sure. However, he is sure that it could not be the case that the external world stays the same while an 'internal' cognitive change takes place.

Relation to the Tractatus

According to the standard reading, in the Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein repudiates many of his own earlier views, expressed in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The Tractatus, as Bertrand Russell saw it (though Wittgenstein took strong exception to Russell's reading), had been an attempt to set out a logically perfect language, building on Russell's own work. In the years between the two works Wittgenstein came to reject the idea that underpinned logical atomism, that there were ultimate "simples" from which a language should, or even could, be constructed.

In remark #23 of Philosophical Investigations he points out that the practice of human language is more complex than the simplified views of language that have been held by those who seek to explain or simulate human language by means of a formal system. It would be a disastrous mistake, according to Wittgenstein, to see language as being in any way analogous to formal logic.

Besides stressing the Investigations' opposition to the Tractatus, there are critical approaches which have argued that there is much more continuity and similarity between the two works than supposed. One of these is the New Wittgenstein approach.

Norman Malcolm credits Piero Sraffa with providing Wittgenstein with the conceptual break that founded the Philosophical Investigations, by means of a rude gesture on Sraffa's part:[33]

"Wittgenstein was insisting that a proposition and that which it describes must have the same 'logical form', the same 'logical multiplicity', Sraffa made a gesture, familiar to Neapolitans as meaning something like disgust or contempt, of brushing the underneath of his chin with an outward sweep of the finger-tips of one hand. And he asked: 'What is the logical form of that?'"

The preface itself, dated January 1945, credits Sraffa for the "most consequential ideas" of the book.[34]

Notes

Remarks in Part I of Investigations are preceded by the symbol "§". Remarks in Part II are referenced by their Roman numeral or their page number in the third edition.

- ↑ Stern, David G. (2004). Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations: An introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 1.

- ↑ In 2009 Blackwell published the fourth edition (ISBN 978-1-4051-5929-6). The first two editions (1953 and 1958) were Anscombe's text; in the anniversary edition (2001), P. M. S. Hacker and J. Schulte are also credited as translators. The fourth edition (2009) was presented as a revision by Hacker and Schulte, crediting Anscombe, Hacker, and Schulte as translators.

- ↑ Wittgenstein (1953), Preface. (All citations will be from Wittgenstein (1953), unless otherwise noted.)

- ↑ Symposia: Symposium sobre información y comunicación, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Estudios Filosóficos, 1963, p. 238

- ↑ §1.

- ↑ §97 quotation:

the order of possibilities, which must be common to both world and thought... must be utterly simple.

- ↑ §309; the original English translation used the word "shew" for "show."

- ↑ §77

- ↑ Jesús Padilla Gálvez Philosophical Anthropology: Wittgenstein's Perspective, p.18

- ↑ Nicholas Bunnin, Jiyuan Yu (2008) The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy, entry for anthropological holism p.34

- ↑ See §3.

- ↑ See §66 (Wittgenstein. PI. Blackwell Publishers, 2001).

- ↑ (II, xi), p.190

- ↑ See §26–34.

- ↑ See §66-§71.

- ↑ See §7.

- ↑ §23

- ↑ §54

- ↑ See §201.

- ↑ §243

- ↑ §246

- ↑ §248

- ↑ §256

- ↑ §265

- 1 2 §293

- ↑ Kripke, Saul. Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. Basil Blackwell Publishing, 1982.

- ↑ Stern 2004:2–7

- ↑ §580.

- ↑ §390

- ↑ §350

- ↑ §307

- ↑ Part II, §xi

- ↑ Norman Malcolm. Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Pier Luigi Porta (2012). "Piero Sraffa's Early Views on Classical Political Economy," Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(6), 1357-1383.

References

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2001) [1953]. Philosophical Investigations. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-23127-7.

- Kripke, Saul (1982). Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. Basil Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-13521-9.

External links

- The first 100 remarks from Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations with Commentary by Lois Shawver.

- Wittgenstein's Beetle – description of the thought experiment from Philosophy Online.

- As The Hammer Strikes in Fillip