Phi Phi Islands

| Mu Ko Phiphi | |

|---|---|

| Archipelago | |

|

Beach surrounded by limestone cliffs, typical of the islands | |

Mu Ko Phiphi | |

| Coordinates: 7°44′00″N 98°46′00″E / 7.73333°N 98.76667°E | |

| Country | Thailand |

| Province | Krabi |

| Amphoe | Mueang Krabi |

| Tambon | Ao Nang |

| Area | |

| • Total | 12.25 km2 (4.73 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1 m (3 ft) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | 2,500 |

| Time zone | ICT (UTC+7) |

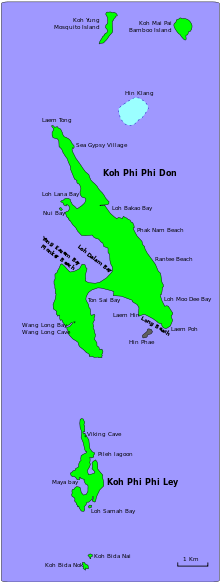

The Phi Phi Islands (Thai: หมู่เกาะพีพี, rtgs: Mu Ko Phiphi, pronounced [mùː kɔ̀ʔ pʰīː.pʰīː]) are an island group in Thailand, between the large island of Phuket and the west Strait of Malacca coast of the mainland. The islands are administratively part of Krabi province. Ko Phi Phi Don ("ko" (Thai: เกาะ) meaning "island" in the Thai language) is the largest island of the group, and is the most populated island of the group, although the beaches of the second largest island, Ko Phi Phi Lee (or "Ko Phi Phi Leh"), are visited by many people as well. The rest of the islands in the group, including Bida Nok, Bida Noi, and Bamboo Island (Ko Mai Phai), are not much more than large limestone rocks jutting out of the sea. The Islands are reachable by speedboats or Long-tail boats most often from Krabi Town or from various piers in Phuket Province.

Phi Phi Don was initially populated by Muslim fishermen during the late-1940s, and later became a coconut plantation. The Thai population of Phi Phi Don remains more than 80% Muslim. The actual population however, if counting laborers, especially from the north-east, is much more Buddhist these days. The population is between 2,000 and 3,000 people (2013).

The islands came to worldwide prominence when Ko Phi Phi Leh was used as a location for the 2000 British-American film The Beach. This attracted criticism, with claims that the film company had damaged the island's environment, since the producers bulldozed beach areas and planted palm trees to make it resemble description in the book,[1] an accusation the film's makers contest. An increase in tourism was attributed to the film's release, which resulted in increases in waste on the Islands, and more developments in and around the Phi Phi Don Village. Phi Phi Lee also houses the "Viking Cave", where there is a thriving industry harvesting edible bird's nest.

Ko Phi Phi was devastated by the Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004, when nearly all of the island's infrastructure was destroyed. As of 2010 most, but not all, of this has been restored.

History

From archaeological discoveries, it is believed that the area was one of the oldest communities in Thailand, dating back to the prehistoric period. It is believed that this province may have taken its name from Krabi, which means "sword". This may come from a legend that an ancient sword was unearthed prior to the city’s founding.

The name "Phi Phi" (pronounced as "pee-pee") originates from Malay. The original name for the islands was Pulau Api-Api ("the fiery isle"). The name refers to the Pokok Api-Api, or "fiery tree" (grey mangrove) which is found throughout the island.

Geography

There are six islands in the group known as Phi Phi. They lie 40 kilometres (25 miles) south-east of Phuket and are part of Hat Nopparat Thara-Ko Phi Phi National Park[2] which is home to an abundance of corals and marine life. There are limestone mountains with cliffs, caves, and long white sandy beaches.[3] The national park covers a total area of 242,437 rai (38,790 ha).

Phi Phi Don and Phi Phi Lee are the largest and most well-known islands. Phi Phi Don is 9.73 square kilometres (3.76 square miles): 8 kilometres (5.0 miles) in length and 3.5 kilometres (2.2 miles) wide. Phi Phi Lee is 2 kilometres (1.2 miles). In total, the islands occupy 12.25 square kilometres (4.73 square miles).

Administration

There are two administrative villages on Ko Phi Phi under the administration of Ao Nang sub-district, Mueang district, Krabi Province. There are nine settlements under these two villages.

The villages are:

- Laem Thong (บ้านแหลมตง, Mu 8, between 300-500 people)

- Ban Ko Mai Phai (about 20 fishermen live on this island)

- Ban Laem Tong

- Ao Loh Bakhao

- Ao Lana

- Ko Phi Phi (บ้านเกาะพีพี, Mu 7, between 1,500 - 2,000 people)

- Ao Maya (about 10 people, mostly in the ranger station)

- Ton Sai, the capital and largest settlement

- Hat Yao

- Ao Lodalum

- Laem Pho

Climate

Hat Noppharat Thara - Mu Ko Phi Phi National Park is influenced by tropical monsoon winds. There are two seasons: the rainy season from May till December and the hot season from January till April. Average temperature ranges between 17–37 °C (63–99 °F). Average rainfall per year is about 2,231 millimetres (87.8 inches), with wettest month being July and the driest February.[2]

Transportation and communication

- Roads

Since the re-building of Ko Phi Phi after the 2004 tsunami, paved roads now cover the vast majority of Ton Sai Bay and Loh Dalum Bay. All roads are for pedestrian use only with push carts used to transport goods and bags. The only permitted motor vehicles are reserved for emergency services. Bicycling is the most popular form of transport in Ton Sai. Bicycles have been banned on the island except for children.

- Air

The nearest airports are at Krabi, Trang, and Phuket. All three have direct road and boat connections.

- Ferry

There are frequent ferry boats to Ko Phi Phi from Phuket, Ko Lanta, and Krabi town starting at 08:30. Last boats from Krabi and Phuket depart at 14:30. In the "green season" (Jun-Oct), travel to and from Ko Lanta is via Krabi town only.

There is a large modern deep water government pier on Tonsai Bay, Phi Phi Don Village, completed in late 2009. It takes in the main ferry boats from Phuket, Krabi, and Ko Lanta. Visitors to Phi Phi Island must pay 20 baht on arrival at the pier. Dive boats, longtail boats, and supply boats have their own drop off points along the piers, making the pier highly efficient in the peak season.

Tourism

The islands feature beaches and clear water that have had their natural beauty protected by national park status. Tourism on Ko Phi Phi, like the rest of Krabi Province, has exploded since the filming of the movie The Beach. In the early 1990s, only adventurous travelers visited the island. Today, Ko Phi Phi is one of Thailand's most famous destinations for scuba diving and snorkeling, kayaking and other marine recreational activities.

The number of tourists visiting the island every year is so high that Ko Phi Phi's coral reefs and marine fauna have suffered major damage as a result.

There are no hotels or other type of accommodation on the smaller island Ko Phi Phi Lee . The only opportunity to spend the night on this island is to take a guided tour to Maya Bay and sleep in a tent.[4]

Medical

There is a small hospital on Phi Phi Island for emergencies. Its main purpose is to stabilize emergencies and evacuate to a Phuket hospital. It is between the Phi Phi Cabana Hotel and the Ton Sai Towers, about a 5–7 minute walk from the main pier.

2004 tsunami

On 26 December 2004, much of the inhabited part of Phi Phi Don was devastated by the Indian Ocean tsunami. The island's main village, Ton Sai (Banyan Tree, Thai: ต้นไทร), is built on a sandy isthmus between the island's two long, tall limestone ridges. On both sides of Ton Sai are semicircular bays lined with beaches. The isthmus rises less than two metres (6.6 feet) above sea level.

Shortly after 10:00 on 26 December, the water from both bays receded. When the tsunami hit, at 10:37, it did so from both bays, and met in the middle of the isthmus. The wave that came into Ton Sai Bay was three metres (9.8 feet) high. The wave that came into Loh Dalum Bay was 6.5 metres (21 feet) high. The force of the larger wave from Loh Dalum Bay pushed the tsunami and also breached low-lying areas in the limestone karsts, passing from Laa Naa Bay to Bakhao Bay, and at Laem Thong (Sea Gypsy Village), where 11 people died. Apart from these breaches, the east side of the island experienced only flooding and strong currents. A tsunami memorial was built to honor the deceased but has since been removed for the building of a new hotel in 2015.

At the time of the tsunami, the island had an estimated 10,000 occupants, including tourists.

Post-tsunami reconstruction

After the tsunami, approximately 70% of the buildings on the island had been destroyed. By the end of July 2005, an estimated 850 bodies had been recovered, and an estimated 1,200 people were still missing. The total number of fatalities is unlikely to be known. Local tour guides cite the figure 4,000. Of Phi Phi Don residents, 104 surviving children had lost one or both parents.

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the island was evacuated. The Thai government declared the island temporarily closed while a new zoning policy was drawn up. Many transient Thai workers returned to their home towns, and former permanent residents were housed in a refugee camp at Nong Kok in Krabi Province.

On 6 January 2005, a former Dutch resident of Phi Phi, Emiel Kok, set up a voluntary organization, Help International Phi Phi ("HI Phi Phi"). HI Phi Phi recruited 68 Thai staff from the refugee camp, as well as transient backpacker volunteers (of whom more than 3,500 offered their assistance), and returned to the island to undertake clearing and rebuilding work. On 18 February 2005, a second organization, Phi Phi Dive Camp,[5] was set up to remove the debris from the bays and coral reef, most of which was in Ton Sai Bay.

By the end of July 2005, 23,000 tonnes of debris had been removed from the island, of which 7,000 tonnes had been cleared by hand. "We try and do as much as possible by hand," said Kok, "that way we can search for passports and identification." The majority of buildings that were deemed fit for repair by government surveyors had been repaired, and 300 businesses had been restored. HI Phi Phi was nominated for a Time Magazine Heroes of Asia award.[6]

As of 6 December 2005, nearly 1,500 hotel rooms were open, and a tsunami early-warning alarm system had been installed by the Thai government with the help of volunteers.

Impact of mass tourism

Since the tsunami, Phi Phi has come under greater threat from mass tourism. Dr Thon Thamrongnawasawat, an environmental activist and member of Thailand's National Reform Council, is campaigning to have Phi Phi tourist numbers capped before its natural beauty is completely destroyed. With southern Thailand attracting thousands more Chinese tourists every day, Dr Thon makes the point that the ecosystem is under threat and is fast disappearing. "Economically, a few people may be enriched, but their selfishness will come at great cost to Thailand", says Dr Thon, a marine biology lecturer at Kasetsart University and an established environmental writer.[7]

More than one thousand tourists arrive on Phi Phi daily. This figure does not include those who arrive by chartered speedboat or yacht. Phi Phi produces about 25 tonnes of solid waste a day, rising to 40 tonnes during the high season. All tourists arriving on the island pay a 20-baht fee at Ton Sai Pier to assist in "keeping Koh Phi Phi clean". "We collect up to 20,000 baht a day from tourists at the pier. The money is then used to pay a private company to haul the rubbish from the island to the mainland in Krabi to be disposed of", Mr Pankum Kittithonkun, Ao Nang Administration Organization (OrBorTor) President, said. The boat takes about 25 tonnes of trash from the island daily, weather permitting. Ao Nang OrBorTor pays 600,000 baht per month for the service. During the high season, an Ao Nang OrBorTor boat is used to help transport the overflow of rubbish. Further aggravating Phi Phi's waste issues is sewage. "We have no wastewater management plant there. Our only hope is that hotels, restaurants and other businesses act responsibly – but I have no faith in them," Mr Pankum said. "They of course have to treat their own wastewater before releasing it into the sea, but they very well could just be turning the devices on before officers arrive to check them." The fundamental issue is that the budget allocated for Ao Nang and Phi Phi is based on its registered population, not on the number of people it plays host to every year, Mr Pankum said.[8]

Gallery

"Sea gypsy" boats, Ko Phi Phi

"Sea gypsy" boats, Ko Phi Phi- Longtail boat on the shore of Phi Phi Island

- Longtail boats, Maya Beach

Bryde's whale swims off the islands

Bryde's whale swims off the islands

See also

References

- ↑ "pggredde". UQ.edu.au. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- 1 2 "Hat Noppharat Thara - Mu Ko Phi Phi National Park". Department of National Parks (DNP) Thailand. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ "Koh Phi Phi". Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT). Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Plunkett, John. "Koh Lanta". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ "PhiPhiDiveCamp.com". Phiphidivecamp.com. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ↑ Marshall, Andrew (2005-10-03). "Help International Phi Phi". Time. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ↑ Sidasathian, Chutima; Morison, Alan (2015-03-21). "Mass Tourism Makes 'a Slum' of Phi Phi". Phuket Wan Tourism News. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ↑ Plerin, Chutharat (2014-10-25). "Special Report: Phi Phi cries for help". Phuket Gazette. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

External links

Geographic data related to Phi Phi Islands at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Phi Phi Islands at OpenStreetMap Ko Phi Phi travel guide from Wikivoyage

Ko Phi Phi travel guide from Wikivoyage

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ko Phi Phi. |