Peter and Paul Fortress

| Peter and Paul Fortress | |

|---|---|

|

Native name Russian: Петропа́вловская кре́пость | |

|

An aerial view of the fortress | |

| Type | Fortress and Museum |

| Location | Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Coordinates | 59°57′00″N 30°19′01″E / 59.950°N 30.317°ECoordinates: 59°57′00″N 30°19′01″E / 59.950°N 30.317°E |

| Built | 1703-1740 |

| Architect | Domenico Trezzini |

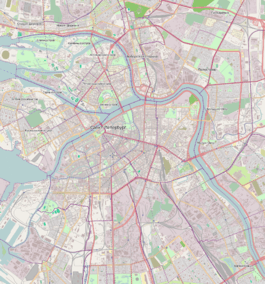

Location of Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg | |

The Peter and Paul Fortress (Russian: Петропа́вловская кре́пость, Petropavlovskaya Krepost) is the original citadel of St. Petersburg, Russia, founded by Peter the Great in 1703 and built to Domenico Trezzini's designs from 1706 to 1740.[1] In the early 1920s, it was still used as a prison and execution ground by the bolshevik government.

Today it has been adapted as the central and most important part of the State Museum of Saint Petersburg History. The museum has gradually become virtually the sole owner of the fortress building, except the structure occupied by the Saint Petersburg Mint (Monetniy Dvor).

History

From foundation until 1917

The fortress was established by Peter the Great on May 16 (by the Julian Calendar, hereafter indicated using "(J)"; May 27 by the Gregorian Calendar) 1703 on small Hare Island by the north bank of the Neva River, the last upstream island of the Neva delta. Built at the height of the Northern War in order to protect the projected capital from a feared Swedish counterattack, the fort never fulfilled its martial purpose. The citadel was completed with six bastions in earth and timber within a year, and it was rebuilt in stone from 1706 to 1740.

From around 1720, the fort served as a base for the city garrison and also as a prison for high-ranking or political prisoners. The Trubetskoy Bastion, rebuilt in the 1870s, became the main prison block. The first person to escape from the fortress prison was the anarchist Prince Peter Kropotkin in 1876. Other people incarcerated in the "Russian Bastille" include Shneur Zalman of Liadi, Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich, Artemy Volynsky, Tadeusz Kościuszko, Alexander Radishchev, the Decembrists, Grigory Danilevsky, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Maxim Gorky, Mikhail Bakunin, Nikolai Chernyshevsky, Leon Trotsky and Josip Broz Tito.

Russian Revolution and beyond

During the February Revolution of 1917, it was attacked by mutinous soldiers of the Pavlovsky Regiment on February 27 (J) and the prisoners were freed. Under the Provisional Government, hundreds of Tsarist officials were held in the Fortress.

The Tsar was threatened with being incarcerated at the Fortress on his return from Mogilev to Tsarskoe Selo on March 8 (J); but he was placed under house arrest. On July 4 (J) when the Bolsheviks attempted a coup, the Fortress garrison of 8,000 men declared for the Bolsheviks. They surrendered to government forces without a struggle on July 6 (J).

On October 25 (J), the fortress quickly fell into Bolshevik hands. Following the ultimatum from the Petrograd Soviet to the Provisional Government ministers in the Winter Palace, after the blank salvo of the Cruiser Aurora at 21.00, the guns of the Fortress fired 30 or so shells at the Winter Palace. Only two hit, inflicting only minor damage, and the defenders refused to surrender– at that time. At 02.10 on the morning of October 26 (J), the Winter Palace was taken by forces under Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko; the captured ministers were taken to the Fortress as prisoners.

In 1918-1921 at least 112 persons including 4 grand dukes were killed here.

In 1924, most of the site was converted to a museum. In 1931, the Gas Dynamics Laboratory was added to the site. The structure suffered heavy damage during the bombardment of the city during WWII by the German army who were laying siege to the city. It has been faithfully restored post-war and is a prime tourist attraction.[1]

Public perception

In Russian folklore, Peter and Paul Fortress was portrayed as a hellish, torturous place, where thousands of prisoners suffered endlessly in filthy, cramped, and grossly overcrowded dungeons amid frequent torture and malnutrition. Such legends had the effect of turning the prison into a symbol of government oppression in the minds of the common folk. In reality, conditions in the fortress were far less brutal than believed; no more than one hundred prisoners were ever kept in the prison at a time, and most prisoners had access to such luxuries as tobacco, writing paper, and literature (including subversive books such as Karl Marx's Das Kapital). When the fortress was liberated during the early stages of the revolution in February 1917, the prison was holding only nineteen recently-incarcerated prisoners: The ringleaders of a mutinous army regiment that had sided with the revolutionaries during the mass protests on the 26th.

Despite their ultimate falsehood, stories about the prison were vital to the spread of revolutionary sentiment. The legends served to portray the government as cruel and indiscriminate in the administration of justice, helping to turn the common mind against Tsarist rule. Many inmates, after being released, wrote chilling and increasingly exaggerated accounts of life there that solidified the structure's horrible image in the public mind and pushed the people further towards dissent. Writers often purposely exaggerated their experiences to garner more hatred for the government; as writer and former Peter and Paul inmate Maksim Gorky would later state, "Every Russian who [had] ever sat in jail...as a 'political' [prisoner]...[considered] it his holy duty to bestow on Russia his memoirs of how he [had] suffered".[2]

Sights

The fortress contains several notable buildings clustered around the Peter and Paul Cathedral (1712–1733), which has a 122.5 m (402 ft) bell-tower (the tallest in the city centre) and a gilded angel-topped cupola.

The cathedral is the burial place of all Russian tsars from Peter I to Alexander III, with the exception of Peter II and Ivan VI. The remains of Nicholas II and his family and entourage were re-interred there, in the side chapel of St. Catherine, on July 17, 1998, the 80th anniversary of their deaths. Toward the end of 2006, the remains of Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna were brought from Roskilde Cathedral outside Copenhagen and reinterred next to her husband, Alexander III.

The newer Grand Ducal Mausoleum (built in the Neo-Baroque style under Leon Benois's supervision in 1896-1908) is connected to the cathedral by a corridor. It was constructed in order to remove the remains of some of the non-reigning Romanovs from the cathedral, where there was scarcely any room for new burials. The mausoleum was expected to hold up to sixty tombs, but by the time of the Russian Revolution, there were thirteen. The latest burial was of Nicholas II's first cousin once removed, Grand Duke Vladimir Cyrilovich (1992). The remains of his parents, Grand Duke Cyril Vladimirovich and his wife Viktoria Fyodorovna, were transferred to the mausoleum from Coburg in 1995.

Other structures inside the fortress include the still functioning mint building [1] (constructed to Antonio Porta's designs under Emperor Paul), the Trubetskoy Bastion with its grim prison cells, and the city museum. According to a centuries-old tradition, a cannon is fired each noon from the Naryshkin Bastion. Annual celebrations of the city day (May 27) are normally centered on the island where the city was born.

The fortress walls overlook sandy beaches that have become among the most popular in St. Petersburg. In summer, the beach is often overcrowded, especially when a major sand festival takes place on the shore.

- Views of the fortress

Peter and Paul Fortress. View across the Neva River

Peter and Paul Fortress. View across the Neva River Entrance from Ioannovsky Bridge

Entrance from Ioannovsky Bridge

- View of the fortress and cathedral from the Neva

References

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter & Paul Fortress. |

- (in Russian) Official webpage

- Official site of museum complex

- Satellite photo, via Google Maps

- Peter & Paul Fortress at www.spb-city.com