Peter Krešimir IV of Croatia

| Peter Krešimir IV the Great | |

|---|---|

|

Statue of Petar Krešimir IV in Šibenik | |

| King of Croatia and Dalmatia | |

| Reign | 1058–1074/5 |

| Coronation | 1059 |

| Predecessor | Stephen I |

| Successor | Demetrius Zvonimir |

| Born | Venice ? |

| Died | 1074/5 |

| Burial | Church of St. Stephen, Solin |

| House |

House of Trpimirović, House of Krešimirović |

| Father | Stephen I of Croatia |

| Mother | Joscella (Hicela) Orseolo |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Peter Krešimir IV, called the Great (Croatian: Petar Krešimir IV. Veliki, Latin: Petrus Cresimir) (died 1075), was King of Croatia and Dalmatia from 1059 to his death in 1074/5.[1] He was the last great ruler of the Krešimirović branch of the House of Trpimirović.

Under his rule the Croatian realm reached its peak territorially, earning him the sobriquet "the Great", otherwise unique in Croatian history.[2] He kept his seat at Nin and Biograd na Moru,[3] however, the city of Šibenik holds a statue of him and is sometimes called Krešimir's city ("Krešimirov grad", in Croatian) because he is generally credited as the founder.[4][5]

Biography

Early years

Peter Krešimir was born as one of two children to king Stephen I (Stjepan I) and his wife Hicela, daughter of the Venetian Doge Pietro II Orseolo.i[›][6]

Krešimir succeeded his father Stephen I upon his death in 1058 and was crowned the next year. It is not known where his coronation took place, but some historians suggest Biograd as a possibility.[7]

From the outset, he continued the policies of his father, but was immediately requested in letter by Pope Nicholas II first in 1059. and then in 1060 to reform the Croatian church in accordance with the Roman rite. This was especially significant to the papacy in the aftermath of the Great Schism of 1054, when a papal ally in the Balkans was a necessity. This was in accordance with the visit of the papal legate Mainardius in 1060, Kresimir and the upper nobility lent their support to the pope and the church of Rome.

The lower nobility and the peasantry, however, were far less well-disposed to reforms. The Croatian priesthood was aligned towards Byzantine orientalism, including having long beards and marrying. More so, the ecclesiastical service was likely practiced in the native Slavonic (Glagolitic), whereas the pope demanded practice in Latin. This caused a rebellion of the clergy led by a certain priest named Vuk (Ulfus), who was referenced as newcomer to the kingdom in sources. Vuk had presented the demands and gifts of the Croats to the Pope during his stay in Rome, but was told nothing could be accomplished without the consent of the Split see and the king.[8] They protested against celibacy and the Latin liturgy in 1063, but they were proclaimed heretical at a synod of 1064. and excommunicated, a decision which Krešimir supported. Krešimir harshly quelled all opposition and sustained a firm alignment towards western Romanism, with the intent of more fully integrating the Dalmatian populace into his realm. In turn, he could then use them to balance the power caused by the growing feudal class. By the end of Krešimir's reign, feudalism had made permanent inroads into Croatian society and Dalmatia had been permanently associated with the Croatian state.[9]

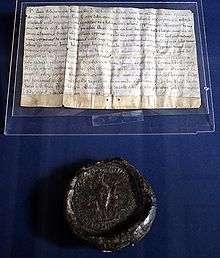

The income from the cities further strengthened Krešimir's power, and he subsequently fostered the development of more cities, such as Biograd, Nin, Šibenik, Karin, and Skradin. He also had several monasteries constructed, like the Benedictine monasteries of St. John the Evangelist (1060) and St. Thomas (c. 1066) in Biograd,[10] and donated much land to the Church. In 1066, he granted a charter to the new monastery of St.Mary in Zadar, where the founder and first nun was his cousin, the Abbess Čika. This remains the oldest Croatian monument in the city of Zadar, and became a spearhead for the reform movement. Several other Benedictine monasteries were also founded during his reign, including the one in Skradin. During the same year, he gave his nephew Stephen Trpimirović the office of Duke of Croatia, which designated him as his co-ruler and successor.[11]

In 1067, the northern part of the kingdom was invaded by Ulric I, Margrave of Carniola, who occupied a part of Kvarner and the eastern coast of Istria, the March of Dalmatia. As the king was at that time preoccupied with the liturgical issues and reforms in Dalmatia, these parts were eventually liberated by his ban Demetrius Zvonimir.[12]

Territorial policy

Krešimir greatly expanded Croatia along the Adriatic coastland and in the mainland eastwards.[7] He made the ban of Slavonia, Dmitar Zvonimir, of the related Svetoslavić brand of his house, Ban of Croatia, and subsequently elevated him as his principal adviser with the title Duke of Croatia. This act brought Slavonia into the Croatian fold definitively.

Around this time, Krešimir was rumored to have murdered his brother Gojslav, who had served as the ban of Croatia until 1070. Eventually, when the rumors reached abroad, Pope Alexander II sent one of his delegates to inquire about the death of Gojslav. Only after the monarch and 12 Croatian župans had taken oath that he did not kill his brother, the Pope symbolically restored the royal power to Krešimir.[13]

It was for the first time that the high ranking office of ban started to branch during his rule, as multiple bans were for the first time mentioned in 1067. It is known that, apart from the ban of Croatia, the banate of Slavonia existed during this period, which was at this time likely held by Krešimir's successor Demetrius Zvonimir.[10][14] The city of Šibenik is for the first time mentioned during his rule in 1066, which was his seat for some time and is for these reasons referred as "Krešimir's city" in modern times.[15]

In 1069, he gave the island of Maun, near Nin, to the monastery of St. Krševan in Zadar, in thanks for the "expansion of the kingdom on land and on sea, by the grace of the omnipotent God" (quia Deus omnipotens terra marique nostrum prolungavit regnum). In his surviving document, Krešimir nevertheless did not fail to point out that it was "our own island that lies on our Dalmatian sea" (nostram propriam insulam in nostro Dalmatico mari sitam, que vocatur Mauni).[16]

Relations with Byzantium and the Normans

In 1069, he had the Byzantine Empire recognize him as supreme ruler of the parts of Dalmatia Byzantium had controlled since the Croatian dynastic struggle of 997.[17] At the time, the empire was at war both with the Seljuk Turks in Asia and the Normans in southern Italy, so Krešimir took the opportunity and, avoiding an imperial nomination as proconsul or eparch, consolidated his holdings as the regnum Dalmatiae et Chroatia. This was not a formal title, but it designated a unified political-administrative territory, which had been the chief desire of the Croatian kings.[16]

During Krešimir's reign, the Normans from southern Italy first became involved in Balkan politics and Krešimir soon came in contact with them. After the 1071 Battle of Manzikert, where the Seljuk Turks routed the Eastern Imperial army, the Diocleans, Serbs and other Slavs instigated a rebellion of boyars in Macedonia and in 1072, Krešimir is alleged to have lent his aid to this uprising. In 1075, the Normans under Peter II of Trani invaded the Dalmatian possessions of Croatia from southern Italy, most likely at the command of the Pope, who had been in a quarrel with the king of Croatia over papal politics towards his kingdom.[18] During the invasion, the Norman count Amico of Giovinazzo besieged the island of Rab for almost a month (14 April to early May). He failed in his siege of Rab, but he managed to take the island of Cres on 9 May. It was during these clashes that the Croatian king himself was captured by Amico at an unidentified location. In return for liberation, he was forced to relinquish many cities, including both his capitals, as well as Zadar, Split, and Trogir. His followers, such as the Bishop of Cres, also collected a large ransom. However, he was not liberated. Over the next two years, the Republic of Venice expelled the Normans and secured the cities for themselves.[19]

Death and succession

Near the end of his reign, Peter Krešimir had no sons, but only a daughter, Neda. His brothers were dead, so his death meant the end of the usurping Krešimir III of Croatia branch of the Trpimirović dynasty. Peter Krešimir designated his cousin Demetrius Zvonimir, duke of Slavonia, as his heir, which restored the Svetoslav Suronja branch of the dynasty. According to some historians, Zvonimir deposed Peter. It is uncertain whether Peter died in a Norman prison during the first half of 1075.[10] According to Johannes Lucius, an usurper, Slavac, succeeded to the throne sometime in 1074 and reigned only for a year before Zvonimir succeeded.[17][20]

Krešimir was buried in the church of St. Stephen[21] in Solin, together with the other dukes and kings of Croatia. Several centuries later the Ottoman Turks destroyed the church, banished the monks who had preserved it, and destroyed the graves.[22]

Legacy

Krešimir is, by some historians, regarded as one of the greatest Croatian rulers. Thomas the Archdeacon named him "the great" in his work Historia Salonitana during the 13th century for his significance in unifing the Dalmatian coastal cities with the Croatian state and accomplishing a peak in Croatia's territorial extent. The RTOP-11 of the Croatian navy was named after Krešimir. The city of Šibenik holds a statue of him and some schools in the vicinity are named after Krešimir.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Peter Krešimir IV of Croatia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

^ i: It is questionable if Hicela was actually married to Stjepan I (the son of Krešimir III) since it is also probable that historical sources mix him with another personality with the same name, this figure was the son of Svetoslav Suronja, and later a close friend of the Venetian doge.

- ↑ http://www.hr/hrvatska/povijest/vladari

- ↑ Ante Oršanić, "Hrvatski orač", 1939.

- 1 2 http://arhinet.arhiv.hr/_DigitalniArhiv/Monumenta/HR-HDA-876-7.htm

- ↑ Šibenik – a story of four citadels

- ↑ Dragutin Pavličević, Povijest Hrvatske. Zagreb, 2007.

- ↑ Marek, Miroslav. "italy/orseolo.html". Genealogy.EU.

- 1 2 http://crohis.com/knjige/Sisic%20-%20pregled/17.%20Petar%20Kresimir%20IV.PDF

- ↑ Šišić, p. 516

- ↑ Marcus Tanner, Croatia – a nation forged in war – Yale University Press, New Haven 1997 ISBN 0-300-06933-2

- 1 2 3 Ferdo Šišić, Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600 – 1918 Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ↑ Šišić, p. 518

- ↑ Nada Klaić, Povijest Hrvata u ranom srednjem vijeku, Zagreb 1975., p. 377-379

- ↑ Tomislav Raukar, Hrvatsko srednjovjekovlje, Školska Knjiga, Zagreb, 1997 pp. 47-48

- ↑ Šišić, p. 526

- ↑ Foster, Jane (2004). Footprint Croatia, Footprint Handbooks, 2nd ed. p. 218. ISBN 1-903471-79-6

- 1 2 Kralj Petar Krešimir IV.

- 1 2 Ferdo Šišić, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara;;, 1925, Zagreb ISBN 86-401-0080-2

- ↑ Croatia in the Early Middle Ages: A Cultural Survey, HAZU and AGM, Zagreb p. 204 - 205

- ↑ N. Klaić, I. Petricioli, Zadar u srednjem vijeku do 1409., Filozofski fakultet Zadar, 1976

- ↑ Johannes Lucius, De regno Dalmatiae et Croatiae

- ↑ Thomas e. c. 55: "Ibi namque magnificus vir Cresimir rex. in atrio videlicet basilice Sancti Stephani tumulatus est cum pluribus aliis regibus et reginis"

- ↑ http://www.solin.hr/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=50&Itemid=192

- ↑ http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11776a.htm

Literature

- Ferdo Šišić, Povijest Hrvata u vrijeme narodnih vladara, 1925, Zagreb ISBN 86-401-0080-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Krešimir IV of Croatia. |

- (in Croatian) Povijest Hrvatske I. (R. Horvat)/Petar Krešimir

- A romantic portrait of Kresimir.

- Map of Kingdom of Croatia during Kresimir IV.

| Peter Krešimir IV of Croatia Died: 1074/5 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Stephen I |

King of Croatia 1058–1074 |

Succeeded by Demetrius Zvonimir |