Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi

| Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi Переяслав-Хмельницький | ||

|---|---|---|

| City | ||

|

Architectural landmarks in the town centre | ||

| ||

Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi | ||

| Coordinates: 50°03′58″N 31°26′32″E / 50.06611°N 31.44222°ECoordinates: 50°03′58″N 31°26′32″E / 50.06611°N 31.44222°E | ||

| Country |

| |

| Oblast |

| |

| Major city | Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi | |

| Founded | 907 | |

| Magdeburg rights | 1585 | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 32 km2 (12 sq mi) | |

| Population (2013) | ||

| • Total | 27,945 | |

| • Density | 870/km2 (2,300/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | |

| Zip code | 08400–08409 | |

| Area code(s) | +380 4567 | |

Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi (Ukrainian: Перея́слав-Хмельни́цький, translit. Pereyáslav-Khmel′nýts′kyi; also referred to as Pereyaslav-Khmelnytskyy) is an ancient city in the Kiev Oblast (province) of central Ukraine, located on the confluence of Alta and Trubizh rivers some 95 km (59.03 mi) south of the nation's capital Kiev. Until 1943, the city was known as Pereyaslav. Population: 27,945 (2013 est.)[1].

Serving as the administrative center of the Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi Raion (district), Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi itself is designated as a city of regional significance and does not belong to the raion. With its current estimated population around 30,000, and over 20 museums, Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi is often described as a "living museum"[2] and granted status of a History and Ethnography Reserve (Ukrainian: історико-етнографічний заповідник).

History

Medieval Kiev Rus city

Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi played a significant role in the history of Ukraine. It was mentioned for the first time in the text of the Rus' treaty with the Byzantine Empire[2] (911) as Pereyaslav-Ruskyi, to distinguish it from Pereyaslavets in Bulgaria. Vladimir I, Prince of Kiev built here in 992 the large fortress to protect the southern limits of Kievan Rus' from raids of nomads from steppes of currently Southern Ukraine. The city was the capital of the Principality of Pereiaslavl' from the middle of the 11th century until its demolition by Tatars in 1239, during the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus'.

Lithuania and Poland

In the 14th century Pereiaslav was annexed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Since 1471 it was part of the Kiev Voivodeship, which in 1569 became part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. In 1585, Polish King Stephen Báthory granted Perejasław Magdeburg city rights. It was a royal city of Poland.

Cossack Ukraine

In the second half of the 16th century Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi became a regimental city of the Ukrainian Cossacks. Here in 1654 Bohdan Khmelnytsky held the controversial "Pereyaslav Convent", where the Ukrainian Cossacks had voted for a military alliance with Muscovy and accepted the Treaty of Pereyaslav. The treaty led to the establishment of the Cossack Hetmanate in left-bank Ukraine under the Tsardom of Russia, and to the outbreak of the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667). The town known as Pereiaslav at that time, and later as Pereiaslav-Poltavskyi. According to the Truce of Andrusovo in 1667, Pereiaslav became part of Russia.

Soviet museum center

Upon the end of World War II, the Soviet government, keen to glorify the Treaty of Pereyaslav as the ground for Ukraine's subordination to Russia, renamed Pereiaslav to Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi in 1943 to stress Bohdan Khmelnytskyi's role of that event. Later, the otherwise obscure town was established as a dedicated museum and tourism center.

Notable people from Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi

- Sholem Aleichem, Jewish-Ukrainian Yiddish writer and playwright

- Hanna Knyazyeva-Minenko (born 1989), Ukrainian and Israeli triple jumper and long jumper

- Louise Nevelson, American sculptor

- Pavlo Teteria, Ukrainian Hetman

Tourist attractions

The most significant landmarks of Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi are:

- Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions in Middle Naddnipryanschina, presenting the architecture and traditions of Ukrainians from ancient times up to the 19th century, which includes submuseums: Museum of Bread, Museum of Land Transportation, Museum of Rushnyks (Ukrainian Decorative Towels), Museum of Space Exploration, Museum of Postal Services, Museum of Beekeeping, Museum of Applied and Decorative Arts, Museum of Ukrainian Traditional Rituals, Museum of Archeology, Museum of the Cossack Glory, Museum of Trypillya Culture, Museum of Ukrainian Traditional Dress, etc.

- Excavated ruins of buildings from the 10–11th centuries.

- St. Michael's church (1646–66)

- Ascension monastery (with cathedral built in 1695–1700).

Jewish Community

The first mention of the Jewish community of Pereiaslav dates to 1620, when the townspeople complained to King Sigismund of the growing number and influence of Jews in Pereiaslav. Denying Jews the right to keep breweries, malt-houses and distilleries, having already prohibited them to engage in farming, the King ordered his commissioners to consider the other rights of Jews. Three years later, an agreement was signed allowing the Jews to enjoy all of the rights and liberties of urban citizens. This agreement was confirmed by King Sigismund.

Pereyaslav Jews were among the first to be killed during the first Khmelnytskyi uprising. Chronicler Nathan Hannover writes: «And a lot of holy communities, based not far from the place of battle and unable to flee, like the holy communities of Pereiaslav, Baryshivka, Pyryatin, Borispil, Lubny, Lokhvitsa and the surrounding communities, died as martyrs of various cruel and heinous kinds of slaughter...» («Yeven metsula», p. 94). Another chronicler, Rabbi Meir of Schebrzheschina, provides a detailed story: «The sacred community of Pereiaslav had drunk from the cup of bitterness several times; perplexed Jews fled to the sacred community of Borisovka (NB. probably Baryshivka). But the rebels also came there and slaughtered many Jews including infants. The local non-Jews pitied those who survived and brought them back to Pereiaslav, where they remained locked up like prisoners in their homes, because they were afraid to be seen by the rebels. At night they did not know what the morning would bring, and in the morning - what the evening promised».

Sholom Aleichem was born in Pereyaslav in 1859. He spent his childhood in the town of Voronkiv, but when the family became impoverished he returned to Pereiaslav, where he studied at the Russian gymnasium until 1876. In 1879, after a (temporarily) unsuccessful attempt to court Olga Loeva, he again returned to Pereiaslav for several years. The town is described in detail in his autobiographical prose. In the town's 'ethnographic reserve', there is a museum dedicated to him. Additional Comments: ...After the 1654 Pereyaslav Council, the remnants of the Pereyaslav Jewish community fell under the patronage of Russia. The Left Bank Jews were allowed to stay in their homes, but the townspeople of Pereyaslav presented to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich the law of 1620 limiting the rights of Jews, which was confirmed by the Tsar. Information about Pereyaslav Jews disappears from the same year 1654.

The new community emerged in the late 18th century. According to the tax books of 1801, there were 5 Christian merchants, no Jewish merchants; 844 Christian townspeople and 66 Jewish townspeople. According to the audit of 1847 there was only one "Pereyaslavskoe’ Jewish community in the district, consisting of 1,519 people. According to the census in 1897, there were 185,000 inhabitants in the district, among them 9,857 Jews, including in Pereyaslav - 14,614 residents, of whom 5,754 were Jews. In 1910, three Jewish schools operated in Pereiaslav: first grade primary boys school, a private boys school, and a Talmud-Torah. At the end of the 19th century, the synagogue was built, it survived the war and has preserved until now – the factory of woven products named after B. Khmelnitsky is operating there.

On 30 June – 2 July 1881 there was a brutal pogrom against the Jews in Pereiaslav. Among the victims were Jews who had fled here after the Kiev pogrom. From Pereiaslav, the unrest spread to the surrounding areas. In June 1919, Ataman Zeleniy arranged a pogrom in Pereiaslav and 20 people were killed. By 1921, a Jewish 'self-defence' organisation had been founded in Pereiaslav. In autumn 1941, on the outskirts of the city (the present territory of the Altitsky cemetery), 800 Jewish residents of Pereiaslav were shot. According to elderly residents, the exact date of the shooting was 4–5 November, however, the memorial plate indicates a different date – 6–8 October. On 19 May 1943, after a raid, 7 more Jewish women and 1 man were shot, and buried in the Altitsky cemetery.

The current Jewish population of Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi numbers fewer than 100. The community office is located in the building of the former synagogue.

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi is twinned with:

-

Mozhaysk, Russia

Mozhaysk, Russia -

Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia

Pereslavl-Zalessky, Russia -

Vileyka, Belarus

Vileyka, Belarus -

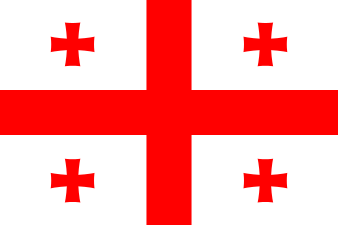

Mtskheta, Georgia

Mtskheta, Georgia -

Paide, Estonia

Paide, Estonia -

Kočani, Macedonia

Kočani, Macedonia

Gallery

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Museum of folk architecture and way of life of Middle Naddnipryanschina. |

Coat of arms of Pereyaslav adopted in 1620.

Coat of arms of Pereyaslav adopted in 1620. Replica of a ХІ century Kievan Rus house in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions

Replica of a ХІ century Kievan Rus house in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions- An old post office in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions

The Rushnyk Museum, in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions

The Rushnyk Museum, in the Museum of Folk Architecture and Household Traditions An avenue in central Pereyaslav

An avenue in central Pereyaslav A street in downtown Pereyaslav

A street in downtown Pereyaslav A church in the Old Town of Pereyaslav

A church in the Old Town of Pereyaslav A monument dedicated to the Treaty of Pereyaslav in the main square

A monument dedicated to the Treaty of Pereyaslav in the main square Bohdan Khmelnytsky square in Pereyaslav

Bohdan Khmelnytsky square in Pereyaslav

References

- ↑ "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Pereyaslav Khmelnytsky – a town of museums", Welcome to Ukraine Magazine, March 2007