Lunar eclipse

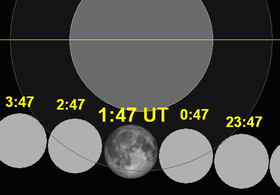

April 15, 2014 |

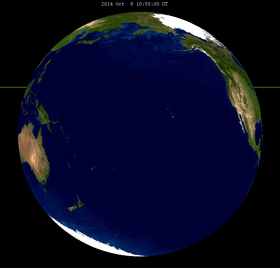

October 8, 2014 |

April 4, 2015 |

September 28, 2015 |

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes directly behind the Earth into its umbra (shadow). This can occur only when the sun, Earth, and moon are aligned (in "syzygy") exactly, or very closely so, with the Earth in the middle. Hence, a lunar eclipse can occur only the night of a full moon. The type and length of an eclipse depend upon the Moon's location relative to its orbital nodes.

A total lunar eclipse has the direct sunlight completely blocked by the earth's shadow. The only light seen is refracted through the earth's shadow. This light looks red for the same reason that the sunset looks red, due to rayleigh scattering of the more blue light. Because of its reddish color, a total lunar eclipse is sometimes called a blood moon.

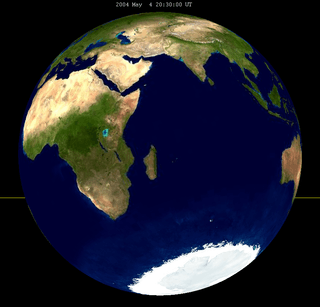

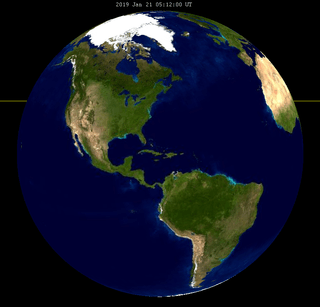

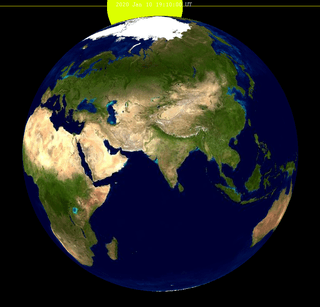

Unlike a solar eclipse, which can be viewed only from a certain relatively small area of the world, a lunar eclipse may be viewed from anywhere on the night side of the Earth. A lunar eclipse lasts for a few hours, whereas a total solar eclipse lasts for only a few minutes at any given place, due to the smaller size of the Moon's shadow. Also unlike solar eclipses, lunar eclipses are safe to view without any eye protection or special precautions, as they are dimmer than the full moon.

For the date of the next eclipse see the section Recent and forthcoming lunar eclipses.

Types of lunar eclipse

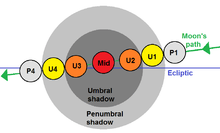

The shadow of the Earth can be divided into two distinctive parts: the umbra and penumbra. Within the umbra, there is no direct solar radiation. However, as a result of the Sun's large angular size, solar illumination is only partially blocked in the outer portion of the Earth's shadow, which is given the name penumbra.

A penumbral eclipse occurs when the moon passes through the Earth's penumbra. The penumbra causes a subtle darkening of the moon's surface. A special type of penumbral eclipse is a total penumbral eclipse, during which the Moon lies exclusively within the Earth's penumbra. Total penumbral eclipses are rare, and when these occur, that portion of the moon which is closest to the umbra can appear somewhat darker than the rest of the moon.

A partial lunar eclipse occurs when only a portion of the moon enters the umbra. When the moon travels completely into the Earth's umbra, one observes a total lunar eclipse. The moon's speed through the shadow is about one kilometer per second (2,300 mph), and totality may last up to nearly 107 minutes. Nevertheless, the total time between the moon's first and last contact with the shadow is much longer and could last up to four hours.[1] The relative distance of the moon from the Earth at the time of an eclipse can affect the eclipse's duration. In particular, when the moon is near its apogee, the farthest point from the Earth in its orbit, its orbital speed is the slowest. The diameter of the umbra does not decrease appreciably within the changes in the orbital distance of the moon. Thus, a totally eclipsed moon occurring near apogee will lengthen the duration of totality.

A central lunar eclipse is a total lunar eclipse during which the moon passes through the centre of the Earth's shadow. These are relatively rare.

Selenelion

A selenelion or selenehelion occurs when both the Sun and the eclipsed Moon can be observed at the same time. This can happen only just before sunset or just after sunrise, and both bodies will appear just above the horizon at nearly opposite points in the sky. This arrangement has led to the phenomenon being referred to as a horizontal eclipse. There are typically a number of high ridges undergoing sunrise or sunset that can see it. Although the moon is in the Earth’s umbra, the Sun and the eclipsed Moon can both be seen at the same time because the refraction of light through the Earth’s atmosphere causes each of them to appear higher in the sky than their true geometric position.[2]

Timing

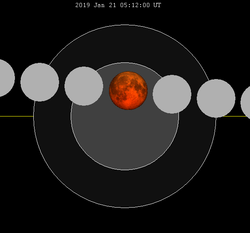

The timing of total lunar eclipses are determined by its contacts:[3]

- P1 (First contact): Beginning of the penumbral eclipse. Earth's penumbra touches the Moon's outer limb.

- U1 (Second contact): Beginning of the partial eclipse. Earth's umbra touches the Moon's outer limb.

- U2 (Third contact): Beginning of the total eclipse. The Moon's surface is entirely within Earth's umbra.

- Greatest eclipse: The peak stage of the total eclipse. The Moon is at its closest to the center of Earth's umbra.

- U3 (Fourth contact): End of the total eclipse. The Moon's outer limb exits Earth's umbra.

- U4 (Fifth contact): End of the partial eclipse. Earth's umbra leaves the Moon's surface.

- P4 (Sixth contact): End of the penumbral eclipse. Earth's penumbra no longer makes contact with the Moon.

Danjon scale

The following scale (the Danjon scale) was devised by André Danjon for rating the overall darkness of lunar eclipses:[4]

- L=0: Very dark eclipse. Moon almost invisible, especially at mid-totality.

- L=1: Dark eclipse, gray or brownish in coloration. Details distinguishable only with difficulty.

- L=2: Deep red or rust-colored eclipse. Very dark central shadow, while outer edge of umbra is relatively bright.

- L=3: Brick-red eclipse. Umbral shadow usually has a bright or yellow rim.

- L=4: Very bright copper-red or orange eclipse. Umbral shadow is bluish and has a very bright rim.

Lunar versus solar eclipse

There is often confusion between a solar and lunar eclipse. While both involve interactions between the sun, Earth, and moon, they are very different in their interactions.

Lunar eclipse appearance

The moon does not completely disappear as it passes through the umbra because of the refraction of sunlight by the Earth's atmosphere into the shadow cone; if the Earth had no atmosphere, the Moon would be completely dark during an eclipse.[5] The reddish coloration arises because sunlight reaching the Moon must pass through a long and dense layer of the Earth's atmosphere, where it is scattered. Shorter wavelengths are more likely to be scattered by the air molecules and the small particles, and so by the time the light has passed through the atmosphere, the longer wavelengths dominate. This resulting light we perceive as red. This is the same effect that causes sunsets and sunrises to turn the sky a reddish color; an alternative way of considering the problem is to realize that, as viewed from the moon, the sun would appear to be setting (or rising) behind the Earth.

The amount of refracted light depends on the amount of dust or clouds in the atmosphere; this also controls how much light is scattered. In general, the dustier the atmosphere, the more that other wavelengths of light will be removed (compared to red light), leaving the resulting light a deeper red color. This causes the resulting coppery-red hue of the moon to vary from one eclipse to the next. Volcanoes are notable for expelling large quantities of dust into the atmosphere, and a large eruption shortly before an eclipse can have a large effect on the resulting color.

March 1504 lunar eclipse

When Christopher Columbus came to the New World—specifically, the north coast of Jamaica—he was able to use European scientific understanding to correctly predict a lunar eclipse. The event is known as the March 1504 lunar eclipse and occurred when Columbus, after he wanted to be seen as god-like, stated that he would make the moon disappear during the night of February 29, 1504. The reason Columbus wanted to prove he could make the moon disappear is because he and his crew were eating a great deal of the inhabitants' food, and the inhabitants refused to feed them anymore. Columbus was right in his prediction, for he used astronomical tables and local clocks in order to predict when the lunar eclipse would happen and was able to convince the inhabitants that he had the power to make the moon disappear and then reappear. After the inhabitants believed that Columbus was truly able to make the moon disappear, they begged him to return the moon to its previous form, and after roughly an allotted amount of time (the amount of time Columbus discerned to be how long the eclipse would last), Columbus agreed to return the moon, and the moon began to reappear. The next day, the inhabitants gave Columbus and his crew the food they desired.[6]

Lunar eclipse in culture

Several cultures have myths related to lunar eclipses or allude to the lunar eclipse as being a good or bad omen. The Egyptians saw the eclipse as a sow swallowing the moon for a short time; other cultures view the eclipse as the moon being swallowed by other animals, such as a jaguar in Mayan tradition, or a three legged toad in China. Some societies thought it was a demon swallowing the moon, and that they could chase it away by throwing stones and curses at it.[7] The Greeks were ahead of their time when they said the Earth was round and used the shadow from the lunar eclipse as evidence.[8] Some Hindus believe in the importance of bathing in the Ganges River following an eclipse because it will help to achieve salvation.[9]

Incans

Similarly to the Mayans, the Incans believed that lunar eclipses occurred when a jaguar would eat the moon, which is why a blood moon looks red. The Incans also believed that once the jaguar finished eating the moon, it could come down and devour all the animals on Earth, so they would take spears and shout at the moon to keep it away.[10]

Mesopotamians

The ancient Mesopotamians believed that a lunar eclipse was when the moon was being attacked by seven demons. This attack was more than just one on the moon, however, for the Mesopotamians linked what happened in the sky with what happened on the land, and because the king of Mesopotamia represented the land, the seven demons were thought to be also attacking the king. In order to prevent this attack on the king, the Mesopotamians made someone pretend to be the king so they would be attacked instead of the true king. After the lunar eclipse was over, the substitute king was made to disappear (possibly by poisoning).[10]

Chinese

In some Chinese cultures, people would ring bells to prevent a dragon or other wild animals from biting the moon.[11] In the nineteenth century, during a lunar eclipse, the Chinese navy fired its artillery because of this belief.[12] During the Zhou Dynasty in the Book of Songs, the sight of a red moon engulfed in darkness was believed to foreshadow famine or disease.[13]

Blood moon

Due to its reddish color, a totally eclipsed moon is sometimes referred to as a "blood moon".[14] In addition, in the 2010s the media started to associate the term with the four full moons of a lunar tetrad, especially the 2014–15 tetrad coinciding with the feasts of Passover and Tabernacles. A lunar tetrad is a series of four consecutive total lunar eclipses, spaced six months apart.[15][16]

Blood Moon is not a scientific term but has come to be used due to the reddish color seen on a Super Moon during the lunar eclipse. When sunlight passes through the earth's atmosphere, it filters and refracts in such a way that the green to violet lights on the spectrum scatters more strongly than the red light. This results the moon to get more red light[17]

Occurrence

Every year, there are at least two lunar eclipses and as many as five, although total lunar eclipses are significantly less common. If one knows the date and time of an eclipse, it is possible to predict the occurrence of other eclipses using an eclipse cycle like the saros.

Recent and forthcoming lunar eclipses

Eclipses only occur during an eclipse season, when the Sun is close to either the ascending or descending node of the Moon.

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 1998–2002 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descending node | Ascending node | |||||

| Saros | Date Viewing |

Type Chart |

Saros | Date Viewing |

Type Chart | |

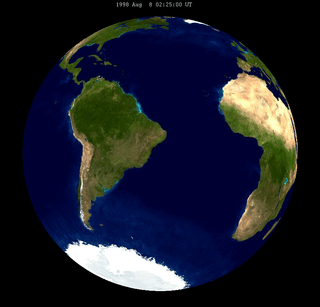

| 109 | 1998 Aug 08 |

Penumbral |

114 | 1999 Jan 31 |

Penumbral | |

| 119 | 1999 Jul 28 |

Partial |

124 | 2000 Jan 21 |

Total | |

| 129 | 2000 Jul 16 |

Total |

134 |

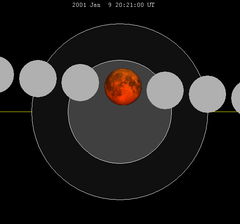

2001 Jan 09 |

Total | |

| 139 |

2001 Jul 05 |

Partial |

144 | 2001 Dec 30 |

Penumbral | |

| 149 | 2002 Jun 24 |

Penumbral | ||||

| Last set | 1998 Sep 06 | Last set | 1998 Mar 13 | |||

| Next set | 2002 May 26 | Next set | 2002 Nov 20 | |||

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 2002–2005 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descending node | Ascending node | |||||

| Saros Photo |

Date View |

Type Chart |

Saros Photo |

Date View |

Type Chart | |

| 111 | 2002 May 26 |

penumbral |

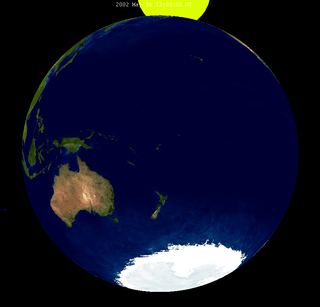

116 |

2002 Nov 20 |

penumbral | |

121 |

2003 May 16 |

total |

126 |

2003 Nov 09 |

total | |

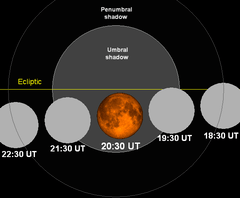

131 |

2004 May 04 |

total |

136 |

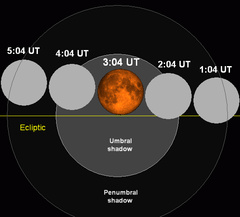

2004 Oct 28 |

total | |

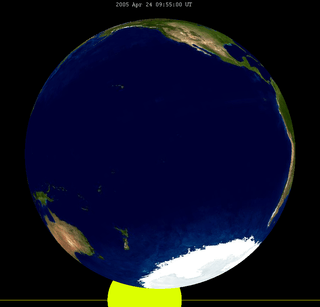

| 141 |

2005 Apr 24 |

penumbral |

146 |

2005 Oct 17 |

partial | |

| Last set | 2002 Jun 24 | Last set | 2001 Dec 30 | |||

| Next set | 2006 Mar 14 | Next set | 2006 Sep 7 | |||

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 2006–2009 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descending node | Ascending node | |||||

| Saros # and photo |

Date Viewing |

Type Chart |

Saros # and photo |

Date Viewing |

Type Chart | |

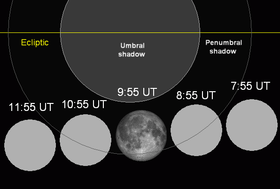

113 |

2006 Mar 14 |

penumbral |

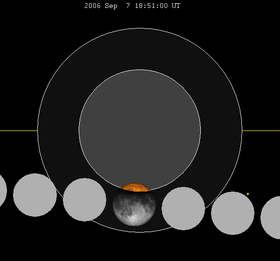

118 |

2006 Sep 7 |

partial | |

123 |

2007 Mar 03 |

total |

128 |

2007 Aug 28 |

total | |

133 |

2008 Feb 21 |

total |

138 |

2008 Aug 16 |

partial | |

143 |

2009 Feb 09 |

penumbral |

148 |

2009 Aug 06 |

penumbral | |

| Last set | 2005 Apr 24 | Last set | 2005 Oct 17 | |||

| Next set | 2009 Dec 31 | Next set | 2009 Jul 07 | |||

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 2009–2013 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending node | Descending node | |||||

| Saros # Photo |

Date Viewing |

Type chart |

Saros # Photo |

Date Viewing |

Type chart | |

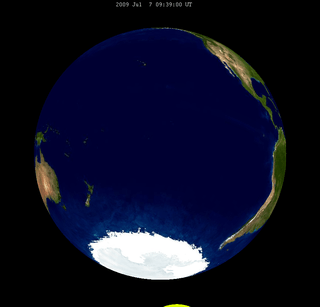

| 110 | 2009 July 07 |

penumbral |

115 |

2009 Dec 31 |

partial | |

120 |

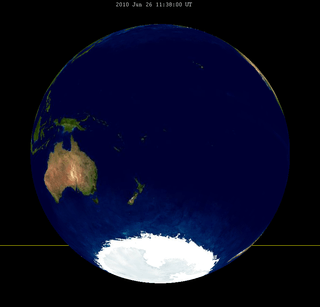

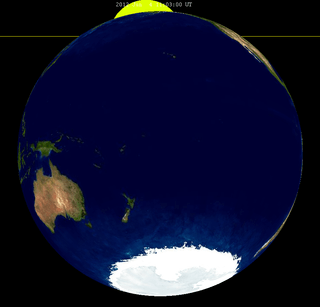

2010 June 26 |

partial |

125 |

2010 Dec 21 |

total | |

130 |

2011 June 15 |

total |

135 |

2011 Dec 10 |

total | |

140 |

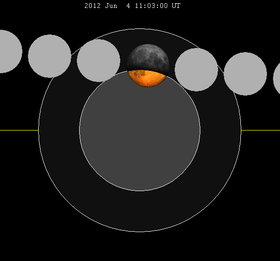

2012 June 04 |

partial |

145 | 2012 Nov 28 |

penumbral | |

| 150 | 2013 May 25 |

penumbral | ||||

| Last set | 2009 Aug 06 | Last set | 2009 Feb 9 | |||

| Next set | 2013 Apr 25 | Next set | 2013 Oct 18 | |||

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 2013–2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending node | Descending node | |||||

| Saros | Viewing date |

Type | Saros | Viewing date |

Type | |

112 |

2013 Apr 25 |

Partial |

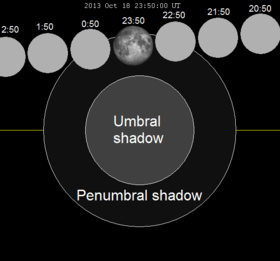

117 | 2013 Oct 18 |

Penumbral | |

122 |

2014 Apr 15 |

Total |

127 |

2014 Oct 08 |

Total | |

132 |

2015 Apr 04 |

Total |

137 |

2015 Sep 28 |

Total | |

| 142 | 2016 Mar 23 |

Penumbral |

147 |

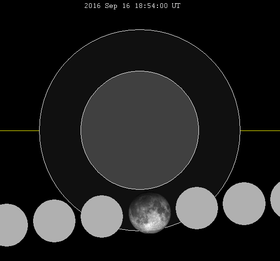

2016 Sep 16 |

Penumbral | |

| Last set | 2013 May 25 | Last set | 2012 Nov 28 | |||

| Next set | 2017 Feb 11 | Next set | 2016 Aug 18 | |||

| Lunar eclipse series sets from 2016–2020 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descending node | Ascending node | |||||

| Saros | Date | Type Viewing |

Saros | Date Viewing |

Type Chart | |

| 109 | 2016 Aug 18 |

Penumbral |

114 |

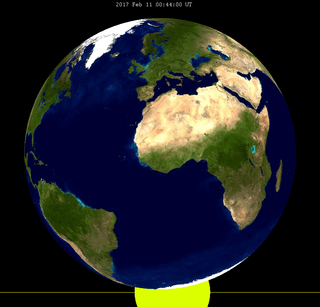

2017 Feb 11 |

Penumbral | |

119 |

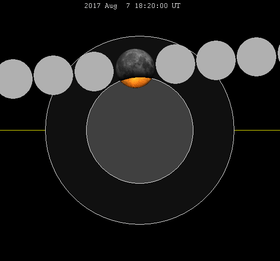

2017 Aug 07 |

Partial |

124 | 2018 Jan 31 |

Total | |

| 129 | 2018 Jul 27 |

Total |

134 | 2019 Jan 21 |

Total | |

| 139 | 2019 Jul 16 |

Partial |

144 | 2020 Jan 10 |

Penumbral | |

| 149 | 2020 Jul 05 |

Penumbral | ||||

| Last set | 2016 Sep 16 | Last set | 2016 Mar 23 | |||

| Next set | 2020 Jun 05 | Next set | 2020 Nov 30 | |||

See also

References

- ↑ Hannu Karttunen. Fundamental Astronomy. Springer.

- ↑ "In Search of Selenelion". Observing Blog - SkyandTelescope.com. 2010-06-26. Retrieved 2011-12-08.

- ↑ Clarke, Kevin. "On the nature of eclipses". Inconstant Moon. Cyclopedia Selenica. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ Paul Deans and Alan M. MacRobert (July 16, 2006). "Observing and Photographing Lunar Eclipses". Sky & Telescope. F+W.

- ↑ Fred Espenak and Jean Meeus. "Visual Appearance of Lunar Eclipses". NASA.

The troposphere and stratosphere act together as a ring-shaped lens that refracts heavily reddened sunlight into Earth's umbral shadow

- ↑ Peterson, Ivars. "The Eclipse That Saved Columbus". ScienceNews. Society for Science & the Public. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ Littmann, Mark; Espenak, Fred; Willcox, Ken (2008). "Chapter 4: Eclipses in Mythology". Totality Eclipses of the Sun (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953209-4. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Pollack, Rebecca. "Ancient Myths Revised with Lunar Eclipse". University of Maryland. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ Ani. "Hindus take a dip in the Ganges during Lunar Eclipse". Yahoo News. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- 1 2 Lee, Jane. "Lunar Eclipse Myths From Around the World". National Geographic. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Quilas, Ma Evelyn. "Interesting Facts and Myths about Lunar Eclipse". LA Times. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ "MYTHOLOGY OF THE LUNAR ECLIPSE".

- ↑ Kaul, Gayatri. "What Lunar Eclipse Means in Different Parts of the World". India.com. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Nigro, Nicholas (2010). Knack Night Sky: Decoding the Solar System, from Constellations to Black Holes. Globe Pequot. pp. 214–5. ISBN 978-0-7627-6604-8.

- ↑ Sappenfield, Mark (13 April 2014). "Blood Moon to arrive Monday night. What is a Blood Moon?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "What is a Blood Moon?". Earth & Sky. 24 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ↑ "All you need to know about the 'blood moon'". theguardian. 28 September 2015.

- ↑ "Total Lunar Eclipse over ESO Headquarters". Retrieved 1 October 2015.

Further reading

- Bao-Lin Liu, Canon of Lunar Eclipses 1500 B.C.-A.D. 3000, 1992

- Jean Meeus and Hermann Mucke Canon of Lunar Eclipses. Astronomisches Büro, Vienna, 1983

- Espenak, F., Fifty Year Canon of Lunar Eclipses: 1986-2035. NASA Reference Publication 1216, 1989

External links

- "Lunar Eclipse Essentials": video from NASA

- Animated explanation of the mechanics of a lunar eclipse, University of South Wales

- U.S. Navy Lunar Eclipse Computer

- NASA Lunar Eclipse Page

- Search among the 12,064 lunar eclipses over five millennium and display interactive maps

- Lunar Eclipses for Beginners

- Tips on photographing the lunar eclipse from New York Institute of Photography

- Lunar Eclipse 08 October 2014 on YouTube