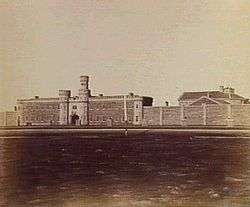

HM Prison Pentridge

| |

| Location | Coburg, Victoria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°44′21″S 144°58′9″E / 37.73917°S 144.96917°ECoordinates: 37°44′21″S 144°58′9″E / 37.73917°S 144.96917°E |

| Status | Closed, under redevelopment |

| Security class | Maximum security |

| Opened | 1851 |

| Closed | 1997 |

| Former name | Pentridge Stockade[1][2][3] |

Her Majesty's Prison Pentridge was an Australian prison that was first established in 1851 in Coburg, Victoria. The first prisoners arrived in 1851. The prison officially closed on 1 May 1997.[4]

Pentridge was often referred to as the "Bluestone College", "Coburg College" or "College of Knowledge". The grounds were originally landscaped by renowned landscape gardener Hugh Linaker.[5]

The site is currently split into two parts.

The northern part of the prison, referred to as the “Pentridge Coburg” or “Pentridge Piazza“ site, is bordered by Champ Street, Pentridge Boulevard, Murray Road and Stockade Avenue.[6] It is currently under development by the developer Shayher Group, who has owned the site since 2013. The southern part of the prison, referred to as the “Pentridge Village” site, is bordered by Pentridge Boulevard, Stockade Avenue, Wardens Walk and Urquhart Street.[7] It is currently owned by the developer Future Estate.

Divisions

The prison was split into many divisions, named using letters of the alphabet.

- A – Short and long-term prisoners of good behaviour but during the late 1980s till its closure it became a scene of many monthly bashings, stabbings and bludgeonings.

- B – Long-term prisoners with behaviour problems

- C – Vagabonds and short term prisoners, where Ned Kelly was imprisoned (Demolished early 1970s)[8]

- D – Remand prisoners

- E – The hospital, later turned into a dormitory division housing short term prisoners

- F – Remand and short-term

- G – Psychiatric problems

- H – High security, discipline and protection

- J – Young Offenders Group- Later for long-term with record of good behaviour

- Jika Jika – maximum security risk and for protection, later renamed K Division

Panopticons

In 2014, archaeological work in the former prison grounds led to the discovery of three rare panopticons (named after Jeremy Bentham’s prison design of 1791) located near the A and B Divisions that were built of bluestone in the 1850s. The first uncovered and excavated was to the north of A division and was built of bluestone in the 1850s. The circular design, with walls coming out from the centre, created wedge shaped 'airing yards' where prisoners would be permitted access for one hour per day without coming into contact with each other. The panopticons fell out of use, due to prison overcrowding, and were largely demolished in the early 1900s.[9] The panopticons were based on the design concepts of British philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham. The footings of the first panopticon that was excavated and uncovered is located to the north of A Division and remains relatively intact. The excavation and uncovering of the other two panopticons next to B Division only revealed the remains of its rubble footings.

Jika Jika high security unit

Jika Jika, opened in 1980 at a cost of 7 million Australian dollars, was a 'gaol within a gaol' maximum security section, designed to house Victoria's hardest and longest serving prisoners.[10] It was awarded the 'Excellence in Concrete Award' by the Concrete Institute of Australia before being closed, 8 years later, amidst controversy after the deaths of five prisoners in 1987.[11]

The design of Jika Jika was based on the idea of six separate units at the end of radiating spines. The unit comprised electronic doors, closed-circuit TV and remote locking, designed to keep staff costs to a minimum and security to a maximum. The furnishings were sparse and prisoners exercised in aviary-like escape proof yards.

In 1983 four prisoners escaped from ‘escape proof’ Jika Jika.[10] When two prison officers were disciplined in relation to the Jika Jika escape a week-long strike occurred.

1987 Jika Jika prison fire

Inmates Robert Wright, Jimmy Loughnan, Arthur Gallagher, David McGauley and Ricky Morris from one side of the unit, and convicted Russell Street bomber Craig Minogue and three other inmates on the other side, sealed off their section doors with a tennis net. Mattresses and other bedding were then stacked against the doors and set on fire. Wright,[10] Loughnan, Gallagher, McGauley[10] and Morris died in the blaze, while Minogue and the three others were evacuated and survived.

Prison works

In 1851, an ad-hoc group of structures built by prison labour using local materials existed. None of these structures survived, other than the boundaries of the prison that were established. The second phase of construction, undertaken in the late 1850s and early 1860s, was the construction of Inspector General William Champ's model prison complex, based on British and American precedents.

In 1924, Pentridge replaced the Melbourne Gaol as the main remand and reception prison for the metropolitan area. In 1929, Melbourne Gaol was closed and its prisoners relocated to Pentridge. The Victorian Government confirmed its intention to close Pentridge and replace it with two new male prisons, each accommodating around 600 prisoners, in December 1993. In April 1995, the Office of Corrections ordered that the six main towers at Pentridge be closed, since most of the high security prisoners from the gaol had been relocated to Barwon as part of the downgrading of Pentridge to a medium security prison. The prison was finally closed in 1997 and sold by the State Government of Victoria.

Since the site was closed, almost all of the buildings identified as being of no significance in the 1996 Pentridge Conservation Management Plan (1996 CMP) prepared by Allom Lovell & Associates have been demolished with the approval of Heritage Victoria. The remaining heritage buildings and landmarks of significance, including A, B, E and H Divisions, B Annexe, Pentridge’s iconic entrance, the Administration Building, the Warden’s Quarters, the Rock-Breaking Yards, the Guard Towers/Posts (or Observation Posts) and the wall surrounding the site have been retained and will undergo restoration works to ensure their stability and preservation into the future.[12] The site as a whole is also classified as a place of state significance by the National Trust of Australia (Victoria) (National Trust).[13] The National Trust has adopted the levels of significance identified in the 1996 CMP.

Future of the site

A number of the iconic heritage building landmarks on the site are located at the Pentridge Coburg site. The heritage features of these landmarks are protected and will be retained and integrated into a new community precinct that will feature a mix of housing types, retail, public open space and open piazza as set out in the Pentridge Coburg Design Guidelines and Masterplan of February 2014 (Pentridge Coburg Masterplan).

This document forms part of the Moreland Planning Scheme and was approved by The Hon. Matthew Guy, the Victorian Minister for Planning between December 2010 to December 2014.[14] A similar Masterplan exists for the Pentridge Village site (Pentridge Village Masterplan).[15] The National Trust has expressed strong concerns about the nature of these Masterplans, which involves building high-density high-rise between the historic divisions.

In 2016, Shayher Group revealed plans for a new urban village to revitalise Pentridge Prison and breathe new life into the historical asset. This includes up to 20 new buildings designed to complement the existing heritage landmarks and numerous community spaces as well as public amenities including an open piazza, forecourt areas and public open space including landscaped gardens as set out in the Pentridge Coburg Masterplan. Shayher Group also revealed its plans to invest several million dollars to restore the roof of A Division, the seven guard towers on site and the rock-breaking yards. These restoration works are anticipated to be completed by late 2018.[16]

Grave sites

The grave site of bushranger Ned Kelly formerly lay within the walls of Pentridge Prison while Ronald Ryan's remains have been returned to his family. Kelly was executed by hanging at the Melbourne Gaol in 1880 and his remains moved to Pentridge Prison in 1929, after his skeleton was disturbed on 12 April 1929 by workmen constructing the present Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) building. Peter Norden, former prison chaplain at Pentridge Prison, has campaigned for the site's restoration.

As of 2011, most of the bodies have been exhumed by archaeologists and have either been re-interred in the original cemetery near D Division, are awaiting identification at the Melbourne morgue or have been returned to their families.[17]

In 2011, Ned Kelly's remains were once again exhumed and returned to his surviving descendants for a proper family burial.[18] The identified remains of Kelly did not include most of his skull.[17] DNA testing also established another complete skull believed to be Kelly's was not in fact his.[17][19]

Executions

- David Bennett 26 September 1932

- Arnold Karl Sodeman 1 June 1936

- Edward Cornelius 26 June 1936

- Thomas Johnson 3 January 1939

- George Green 17 April 1939

- Alfred Bye 22 December 1941

- Eddie Leonski (US soldier, executed on behalf of the United States Army) 9 November 1942

- Jean Lee 19 February 1951

- Norman Andrews 19 February 1951

- Robert David Clayton 19 February 1951

- Ronald Joseph Ryan 3 February 1967

Last execution

Ronald Ryan was the last man executed at Pentridge Prison and in Australia. Ryan was hanged in "D" Division at 8.00 on 3 February 1967 after being convicted of the shooting death of a prison officer during a botched escape from the same prison. Later that day, Ryan's body was buried in an unmarked grave within the "D" Division prison facility.

Notable prisoners

- Dennis Allen – oldest member of the Pettingill family. (d. 1987)

- Garry David – (d. 1993), also known as Garry Webb, responsible for the Community Protection Act 1990.

- Peter Dupas – Australian serial killer.

- Keith Faure – convicted of murdering Lewis Caine and Lewis Moran with Evangelos Goussis during the Melbourne gangland killings was also the basis for the character of Keithy George in the film Chopper.

- Christopher Dale Flannery – aka Mr Rent-a-Kill, hitman.

- Kevin Albert Joiner – murderer, shot dead trying to escape in 1952.

- Ned Kelly – a bushranger. (d. 1880)

- Julian Knight – murdered 7 people in the Hoddle Street Massacre.

- Shelton Lea – poet.

- Eddie Leonski – the Brownout Strangler.

- Craig 'Slim' Minogue – the Russell Street Bomber.

- Clarrie O'Shea – a trade unionist.

- Victor Peirce – a member of the Pettingill family, acquitted of the 1988 Walsh Street police shootings. Killed in 2002.

- Harry Power – a bushranger.

- Mark "Chopper" Read – a gang leader and standover man. (d. 2013)

- Gregory David Roberts – author of Shantaram, escapee of Pentridge who fled to India.

- Ronald Ryan – the last person to be executed in Australia. (d. 1967)

- Frank Penhalluriack – in the 1980s due to trading hours activism.

- Maxwell Carl Skinner[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] – constant escapee, infamous for commandeering a Coburg Tram in one of his escapes.

- William Stanford – a sculptor.

- Stan Taylor – an actor and convicted Russell Street bomber.

- Squizzy Taylor – a gangster.

- John Zarb – the first person to be found guilty of having failed to comply with his call up notice during the Vietnam War.

Timeline

- 1851 Her Majesty’s Prison Pentridge established

- 1929 Melbourne Gaol closed and its prisoners relocated to Pentridge

- 1951 Last woman executed in Australia, Jean Lee is hanged

- 1967 Last person to be executed in Australia, Ronald Ryan (between 1842 and 1967, 186 prisoners were executed)

- 1987 Five prisoners die in a fire in Jika Jika during riots over prison conditions. Craig Minogue and 3 other inmates survived the fire

- 1997 Pentridge is closed

- 1999 The State Government of Victoria sells Pentridge to developers Luciano Crema and Harry Barbon in partnership with Peter and Leigh Chiavaroli

- 2002 Pentridge is split into Pentridge Piazza (also referred to as Pentridge Coburg), controlled by Luciano Crema and Harry Barbon, and Pentridge Village, controlled by Peter and Leigh Chiavaroli

- 2007 Luciano Crema and Harry Barbon sells the Pentridge Coburg site to developers Valad Property Group and Abadeen Group

- 2009 Pentridge Coburg Masterplan and Pentridge Village Masterplan are approved by the Victorian Planning Minister following an extensive period of consultation

- 2013 The Valad Property Group sells the Pentridge Coburg site to developer Shayher Group

- 2014 A revision to the Pentridge Coburg Masterplan is approved by the Victorian Planning Minister

- 2015 Chiavaroli sells the Pentridge Village site to Future Estate. Shayher Group commences construction of the Horizon apartments at the north-east corner of the Pentridge Coburg site

- 2016 Shayher Group rebrands and unveils the Pentridge Coburg site as “Pentridge” and opens the iconic gates to the public, hosting a Community Open Day and the prison's first public historical and interactive art exhibition, “Pentridge Unlocked”. Shayher Group also commences the restoration works on the roof of A Division, the Guard Towers and the Rock-Breaking Yards

Escapes

- 1851 Frank Gardiner - one of fifteen to escape that day

- 1899 Pierre Douar – Suicided after recapture

- 1901 Mr Sparks – never heard of again

- 1901 John O'Connor – Caught in Sydney two weeks later

- 1926 J.K. Monson – caught several weeks later in W.A.

- 1939 George Thomas Howard – caught after two days

- 1940 K.R. Jones – Caught in Sydney two weeks later

- 1951 Victor Franz – caught next day.

- 1952 Kevin Joiner – Shot dead escaping

- 1952 Maxwell Skinner – pushed off prison wall, broke leg[27]

- 1957 Willam O'Malley – caught after 15 minutes

- 1957 John Henry Taylor – caught after 15 minutes

- 1961 Maurice Watson – caught next day

- 1961 Gordon Hutchinson – caught next day[28]

- 1965 Ronald Ryan – caught in Sydney 19 days later

- 1965 Peter Walker – caught in Sydney 19 days later

- 1972 Dennis Denehy – [29]

- 1972 Gary Smedley – [29]

- 1972 Alan Mansell – [29]

- 1972 Henry Carlson – [29]

- 1973 Harold Peckman – [30] caught next day

- 1974 Edward "Jockey" Smith – [31]

- 1974 Robert Hughes –

- 1974 George Carter – [32]

- 1976 John Charles Walker – [33]

- 1977 David Keys – [34]

- 1977 Peter James Dawson and three others[35]

- 1980 Gregory David Roberts (at the time known as Gregory Smith) – escaped in broad daylight with Trevor Jolly and subsequently went to India after a brief period in New Zealand[36]

- 1980 Trevor Jolly – [36]

- 1982 Harry Richard Nylander – [37]

- 1987 Dennis Mark Quinn – [38] Recaptured in New Zealand 19 days later.

Usage in media

- The front gate showing the "HM Prison Pentridge" sign is featured on the cover of Australian band Airbourne's debut album Runnin' Wild.[39]

- Episode 2, "Homecomings" of the 1976 ABCTV adaption of Frank Hardy's novel Power Without Glory features John West picking his brother Frank West up from Pentridge Prison after serving 12 years for rape.

- The 1988 John Hillcoat and Evan English film Ghosts… of the Civil Dead was largely based on events which occurred in Pentridge Prison's infamous Jika Jika Maximum Security prison during the lead up to the 1987 fire.

- The 1994 Australian film Everynight ... Everynight details prison life inside Pentridge's H Division.[40]

- The 2000 Andrew Dominik film Chopper was partially filmed in H Division.

- In the 1997 Australian film The Castle, Wayne was a prisoner of HM Prison Pentridge.

References

- ↑ "PENTRIDGE STOCKADE.". The Argus (Melbourne) (3133). Victoria, Australia. 25 June 1856. p. 4. Retrieved 29 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE CONVICT HULKS.". The Argus (Melbourne) (3152). Victoria, Australia. 17 July 1856. p. 6. Retrieved 29 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE OLD CONVICT HULKS.". The Argus (Melbourne) (12,086). Victoria, Australia. 18 March 1885. p. 6. Retrieved 29 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Egger, Simone; David McClymont (2004). Melbourne. Lonely Planet. p. 69. ISBN 1-74059-766-4.

- ↑ "Mont Park Psychiatric Hospital Precinct (listing RNE100229)". Australia Heritage Places Inventory. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ↑ Identified as “Precinct 9” in Moreland Planning Scheme, clause 1.0 and 5.9 of clause 37.08, Schedule 1 to the Activity Centre Zone.

- ↑ Identified as “Precinct 10” in Moreland Planning Scheme, clause 1.0 and 5.10 of clause 37.08, Schedule 1 to the Activity Centre Zone.

- ↑ "Archaeologists dig major new find at Pentridge Prison". The Age. Fairfax Media. 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ "Archaeologists dig major new find at Pentridge Prison". The Age. Fairfax Media. 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Sawtell, Lydia (2012-04-24). "True Crime Scene details the escapes from Pentridge Prison in its 140-year history". Herald Sun. News Corp Australia. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ O'Toole, Sean (2006). The History of Australian Corrections. UNSW Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-86840-915-4.

- ↑ See generally, Bryce Rawroth Pty Ltd, Former Pentridge Prison, Conservation Management Plan, April 2016, available at: http://pentridgecoburg.com.au/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/Former_Pentridge_Prison_CMP.pdf

- ↑ File number: B1303.

- ↑ Pentridge Coburg Design Guidelines and Masterplan, February 2014, available at: http://www.moreland.vic.gov.au/globalassets/areas/planning/reference-documents/moreland-~-pentridge-coburg-masterplan-2014-approval-pentridge-design-guidelines-and-masterplan-2014.pdf. See also, Moreland Planning Scheme, clause 12 of clause 37.08, Schedule 1 to the Activity Centre Zone.

- ↑ Pentridge Village Pty Ltd Design Guidelines and Masterplan, available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Pentridge-Village-Design-Guidelines-and-Masterplan-2009.pdf

- ↑ See generally, www.pentridgecoburg.com.au.

- 1 2 3 Smith, Jeremy (2011). "Losing the Plot: Archaeological Investigations of Prisoner Burials at the Old Melbourne Gaol and Pentridge Prison". Provenance: The Journal of Public Record Office Victoria (10). ISSN 1832-2522. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ "Ned Kelly farewelled by family". Australian Geographic. Bauer Media Group. 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ "Scientists at the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine have identified the body of Ned Kelly". Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ 19 Jan 1951 – WARDERS WITNESS DARING ESCAPE FROM PENTRIDGE MEL. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 11 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ 20 Jan 1951 – SEARCH FOR GAOL ESCAPEE MELBOURNE, Monday. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 10 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ 23 Jan 1951 – GAOL ESCAPEE SAYS HE HAS REFORMED MELBOURNE, Thu. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04.

- ↑ 19 Jan 1951 – GAOL ESCAPEE RECAPTURED MELBOURNE, Tuesday. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 15 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ 20 Jan 1951 – GAOL ESCAPEE WELL GUARDED MELBOURNE, Wednesday. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 15 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ 15 Jan 1952 – CONVICT MURDERER KILLED IN ESCAPE BID; COMPANION. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 11 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ 16 Jan 1952 – PRISON STAFF COMMENDED; ESCAPE FOILED MELBOURNE. Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. Retrieved on 2011-12-04. Archived 24 July 2012 at Archive.is

- ↑ "Man shot dead in bid to flee gaol". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 April 1952.

- ↑ "Through Roof". The Age. Melbourne. 17 January 1961.

- 1 2 3 4 "Prisoner's death". The Age. Melbourne. 10 May 1972.

- ↑ Dunn, Alan (2 February 1973). "Axe murderer escapes from Pentridge gaol". The Age. Melbourne.

- ↑ "'Jockey' is back facing court again". The Age. Melbourne. 3 December 1989.

- ↑ "Mattress pile clue to gaol escape". The Age. Melbourne. 5 October 1974.

- ↑ "Tighten up order after Pentridge escape". The Age. Melbourne. 28 April 1976.

- ↑ "Prisoner escapes over wall". The Age. Melbourne. 17 October 1977. p. 4.

- ↑ "Prisoner used jail gear for escape". The Age. Melbourne. 20 January 1978. p. 5.

- 1 2 Marshall, Ian (24 July 1980). "No news is dull viewing". The Age. Melbourne. p. 2.

- ↑ Gray, Tony; Eccleston, Roy (21 July 1982). "Prison had two warnings of escape: Toner". The Age. Melbourne. p. 3.

- ↑ Athersmith, Fiona (30 March 1988). "Robber gets 12 more months for escape from Pentridge". The Age. Melbourne. p. 18.

- ↑ Airbourne's official site, accessed 1 August 2009

- ↑ Everynight... Everynight, National Film and Sound Archive, Accessed 8 March 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to HM Prison Pentridge. |

- H.M. Melbourne's Pentridge prison, Urban exploration

- Transforming an historic icon into an urban hub, Pentridge