Cadaverine

| | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Pentane-1,5-diamine | |

| Other names

1,5-Diaminopentane | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 3DMet | B00334 |

| 1697256 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.664 |

| EC Number | 207-329-0 |

| 2310 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Cadaverine |

| PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number | SA0200000 |

| UNII | |

| UN number | 2735 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C5H14N2 | |

| Molar mass | 102.18 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colourless to yellow oily liquid |

| Odor | unpleasant |

| Density | 0.8730 g/mL |

| Melting point | 11.83 °C (53.29 °F; 284.98 K) |

| Boiling point | 179.1 °C; 354.3 °F; 452.2 K |

| soluble | |

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol slightly soluble in ethyl ether |

| log P | −0.123 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.25, 9.13 |

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.458 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS pictograms |  |

| GHS signal word | DANGER |

| H314 | |

| P280, P305+351+338, P310 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 62 °C (144 °F; 335 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

2000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| Related compounds | |

| Related alkanamines |

|

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

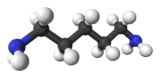

Cadaverine is a foul-smelling diamine compound produced by the putrefaction of animal tissue. Cadaverine is a toxic[1] diamine with the formula NH2(CH2)5NH2, which is similar to putrescine. Cadaverine is also known by the names 1,5-pentanediamine and pentamethylenediamine.

History

Putrescine[2] and cadaverine[3] were first described in 1885 by the Berlin physician Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919).[4]

Production

Cadaverine is the decarboxylation product of the amino acid lysine.[5] This can be done by heating lysine with a small amount of Sodium bicarbonate mixed in. The produced gas should be led to a glass container which is surrounded by ice water. The heating must be done in a glass container, as metals may contaminate the process.

However, this diamine is not purely associated with putrefaction. It is also produced in small quantities by living beings. It is partially responsible for the distinctive odors of urine.[6]

Clinical significance

Elevated levels of cadaverine have been found in the urine of some patients with defects in lysine metabolism. The odor commonly associated with bacterial vaginosis has been linked to cadaverine and putrescine.[7]

- Pentolinium & Pentamethonium are both chemical derivatives of cadaverine.

Toxicity

Cadaverine is toxic in large doses. In rats it has a low acute oral toxicity of 2000 mg/kg body weight, with no-observed-adverse-effect level of 2000 ppm (180 mg/kg body weight/day).[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Lewis, Robert Alan (1998). Lewis' Dictionary of Toxicology. CRC Press. p. 212. ISBN 1-56670-223-2.

- ↑ Ludwig Brieger, "Weitere Untersuchungen über Ptomaine" [Further investigations into ptomaines] (Berlin, Germany: August Hirschwald, 1885), page 43.

- ↑ Ludwig Brieger, "Weitere Untersuchungen über Ptomaine" [Further investigations into ptomaines] (Berlin, Germany: August Hirschwald, 1885), page 39. From page 39: Ich nenne das neue Diamin C5H16N2: "Cadaverin", da ausser der empirischen Zussamsetzung, welche die neue Base als ein Hydrür des Neuridins für den flüchtigen Blick erscheinen lässt, keine Anhaltspunkte für die Berechtigung dieser Auffassung zu erheben waren. (I call the new di-amine, C5H16N2, "cadaverine," since besides its empirical composition, which allows the new base to appear superficially as a hydride of neuridine, no clues for the justification of this view arose.)

- ↑ Brief biography of Ludwig Brieger (in German). Biography of Ludwig Brieger in English.

- ↑ Wolfgang Legrum: Riechstoffe, zwischen Gestank und Duft, Vieweg + Teubner Verlag (2011) S. 65, ISBN 978-3-8348-1245-2.

- ↑ Cadaverine PubChem

- ↑ Yeoman, CJ; Thomas, SM; Miller, ME; Ulanov, AV; Torralba, M; Lucas, S; Gillis, M; Cregger, M; Gomez, A; Ho, M; Leigh, SR; Stumpf, R; Creedon, DJ; Smith, MA; Weisbaum, JS; Nelson, KE; Wilson, BA; White, BA (2013). "A multi-omic systems-based approach reveals metabolic markers of bacterial vaginosis and insight into the disease.". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e56111. PMC 3566083

. PMID 23405259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056111.

. PMID 23405259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056111. - ↑ Til, H.P.; Falke, H.E.; Prinsen, M.K.; Willems, M.I. (1997). "Acute and subacute toxicity of tyramine, spermidine, spermine, putrescine and cadaverine in rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 35 (3-4): 337–348. ISSN 0278-6915. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(97)00121-X.