Human penis

| Human penis | |

|---|---|

|

A flaccid penis | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Genital tubercle, Urogenital folds |

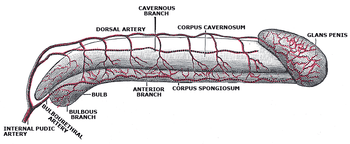

| Artery | Penile artery, Dorsal artery of the penis, deep artery of the penis, artery of the urethral bulb |

| Vein | Dorsal veins of the penis |

| Nerve | Dorsal nerve of the penis |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | 'penis, penes' |

| MeSH | A05.360.444.492 |

| TA | A09.4.01.00222 |

| FMA | 9707 |

The human penis is an external male intromittent organ that additionally serves as the urinal duct. The main parts are the root (radix); the body (corpus); and the epithelium of the penis including the shaft skin and the foreskin (prepuce) covering the glans penis. The body of the penis is made up of three columns of tissue: two corpora cavernosa on the dorsal side and corpus spongiosum between them on the ventral side. The human male urethra passes through the prostate gland, where it is joined by the ejaculatory duct, and then through the penis. The urethra traverses the corpus spongiosum, and its opening, the meatus (/miːˈeɪtəs/), lies on the tip of the glans penis. It is a passage both for urination and ejaculation of semen. (See: male reproductive system.)

Most of the penis develops from the same tissue in the embryo as does the clitoris in females; the skin around the penis and the urethra come from the same embryonic tissue from which develops the labia minora in females.[1][2] An erection is the stiffening and rising of the penis, which occurs during sexual arousal, though it can also happen in non-sexual situations. Spontaneous non-sexual erections frequently occur during adolescence.

The most common form of genital alteration is circumcision, removal of part or all of the foreskin for various cultural, religious and, more rarely, medical reasons. There is controversy surrounding circumcision.

In its relaxed (flaccid, i.e. soft/limp) state, the shaft of the penis has the feel of a dense sponge encased in very smooth eyelid-type skin. The tip, or glans of the penis is darker in color, and covered by the foreskin, if present.

In its fully erect state, the shaft of the penis is rigid, with the skin tightly stretched. The glans of the erect penis has the feel of a raw mushroom. The erect penis may be straight or curved and may point at an upward or downward angle, or straight ahead. It may also have a tendency to the left or right.

While results vary across studies, the consensus is that the average erect human penis is approximately 12.9–15 cm (5.1–5.9 in) in length with 95% of adult males falling within the interval 10.7–19.1 cm (4.2–7.5 in). Neither age nor size of the flaccid penis accurately predicts erectile length.

Anatomy

Parts

- Root of the penis (radix): It is the attached part, consisting of the bulb of penis in the middle and the crus of penis, one on either side of the bulb. It lies within the superficial perineal pouch.

- Body of the penis (corpus): It has two surfaces: dorsal (posterosuperior in the erect penis), and ventral or urethral (facing downwards and backwards in the flaccid penis). The ventral surface is marked by a groove in a lateral direction.

- Epithelium of the penis consists of the shaft skin, the foreskin, and the preputial mucosa on the inside of the foreskin and covering the glans penis. The epithelium is not attached to the underlying shaft so it is free to glide to and fro.[3]

Structure

The human penis is made up of three columns of tissue: two corpora cavernosa lie next to each other on the dorsal side and one corpus spongiosum lies between them on the ventral side.

The enlarged and bulbous-shaped end of the corpus spongiosum forms the glans penis, which supports the foreskin, or prepuce, a loose fold of skin that in adults can retract to expose the glans. The area on the underside of the penis, where the foreskin is attached, is called the frenum, or frenulum. The rounded base of the glans is called the corona. The perineal raphe is the noticeable line along the underside of the penis.

The urethra, which is the last part of the urinary tract, traverses the corpus spongiosum, and its opening, known as the meatus /miːˈeɪtəs/, lies on the tip of the glans penis. It is a passage both for urine and for the ejaculation of semen. Sperm are produced in the testes and stored in the attached epididymis. During ejaculation, sperm are propelled up the vas deferens, two ducts that pass over and behind the bladder. Fluids are added by the seminal vesicles and the vas deferens turns into the ejaculatory ducts, which join the urethra inside the prostate gland. The prostate as well as the bulbourethral glands add further secretions, and the semen is expelled through the penis.

The raphe is the visible ridge between the lateral halves of the penis, found on the ventral or underside of the penis, running from the meatus (opening of the urethra) across the scrotum to the perineum (area between scrotum and anus).

The human penis differs from those of most other mammals, as it has no baculum, or erectile bone, and instead relies entirely on engorgement with blood to reach its erect state. It cannot be withdrawn into the groin, and it is larger than average in the animal kingdom in proportion to body mass.

Size

While results vary across studies, the consensus is that the average erect human penis is approximately 12.9–15 cm (5.1–5.9 in) in length with 95% of adult males falling within the interval 10.7–19.1 cm (4.2–7.5 in). Neither age nor size of the flaccid penis accurately predicted erectile length. Stretched length most closely correlated with erect length.[4][5][6] The average penis size is slightly larger than the median size (i.e., most penises are below average in size).

Length of the flaccid penis does not necessarily correspond to length of the erect penis; some smaller flaccid penises grow much longer, while some larger flaccid penises grow comparatively less.[7] Among all primates, the human penis is the largest in girth, but comparable to chimpanzees and certain other species in length.[8]

A research project, summarizing dozens of published studies conducted by physicians of different nationalities, shows that, worldwide, erect-penis size averages vary between 9.6 and 16 cm (3.8 and 6.3 in). It has been suggested that this difference is caused not only by genetics but also by environmental factors such as fertility medications,[9] culture, diet, and chemical/pollution exposure.[10][11][12] Endocrine disruption resulting from chemical exposure has been linked to genital deformation in both sexes (among many other problems).

The longest officially documented human penis was found by physician Robert Latou Dickinson. It was 34.3 cm (13.5 in) long and 15.9 cm (6.26 in) around.[13]

Normal variations

- Pearly penile papules are raised bumps of somewhat paler color around the base (sulcus) of the glans which typically develop in men aged 20 to 40. As of 1999, different studies had produced estimates of incidence ranging from 8 to 48 percent of all men.[14] They may be mistaken for warts, but are not harmful or infectious and do not require treatment.[15]

- Fordyce's spots are small, raised, yellowish-white spots 1–2 mm in diameter that may appear on the penis, which again are common and not infectious.

- Sebaceous prominences are raised bumps similar to Fordyce's spots on the shaft of the penis, located at the sebaceous glands and are normal.

- Phimosis is an inability to retract the foreskin fully. It is normal and harmless in infancy and pre-pubescence, occurring in about 8% of boys at age 10. According to the British Medical Association, treatment (topical steroid cream and/or manual stretching) does not need to be considered until age 19.

- Curvature: few penises are completely straight, with curves commonly seen in all directions (up, down, left, right). Sometimes the curve is very prominent but it rarely inhibits sexual intercourse. Curvature as great as 30° is considered normal and medical treatment is rarely considered unless the angle exceeds 45°. Changes to the curvature of a penis may be caused by Peyronie's disease.

Development

Differences between female and male organs

In the developing fetus, the genital tubercle develops into the glans of the penis in males and into the clitoral glans in females; they are homologous. The urogenital fold develops into the skin around the shaft of the penis and the urethra in males and into the labia minora in females.[1] The corpora cavernosa are homologous to the body of the clitoris; the corpus spongiosum is homologous to the vestibular bulbs beneath the labia minora; the scrotum, homologous to the labia majora; and the foreskin, homologous to the clitoral hood.[1][16] The raphe does not exist in females, because there, the two halves are not connected.

Penile growth and puberty

On entering puberty, the penis, scrotum and testicles will enlarge toward maturity. During the process, pubic hair grows above and around the penis. A large-scale study assessing penis size in thousands of 17- to 19-year-old males found no difference in average penis size between 17-year-olds and 19-year-olds. From this, it can be concluded that penile growth is typically complete not later than age 17, and possibly earlier.[17]

Physiological functions

Urination

In males, the expulsion of urine from the body is done through the penis. The urethra drains the bladder through the prostate gland where it is joined by the ejaculatory duct, and then onward to the penis. At the root of the penis (the proximal end of the corpus spongiosum) lies the external sphincter muscle. This is a small sphincter of striated muscle tissue and is in healthy males under voluntary control. Relaxing the urethra sphincter allows the urine in the upper urethra to enter the penis properly and thus empty the urinary bladder.

Physiologically, urination involves coordination between the central, autonomic, and somatic nervous systems. In infants, some elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury, urination may occur as an involuntary reflex. Brain centers that regulate urination include the pontine micturition center, periaqueductal gray, and the cerebral cortex.[18] During erection, these centers block the relaxation of the sphincter muscles, so as to act as a physiological separation of the excretory and reproductive function of the penis, and preventing urine from entering the upper portion of the urethra during ejaculation.[19]

Voiding position

The distal section of the urethra allows a human male to direct the stream of urine by holding the penis. This flexibility allows the male to choose the posture in which to urinate. In cultures where more than a minimum of clothing is worn, the penis allows the male to urinate while standing without removing much of the clothing. It is customary for some men to urinate in seated or crouched positions. The preferred position may be influenced by cultural or religious beliefs.[20] Research on the medical superiority of either position exists, but the data are heterogenic. A meta-analysis[21] summarizing the evidence found no superior position for young, healthy males. For elderly males with LUTS however, in the sitting position compared to the standing:

- the post void residual volume (PVR, ml) was significantly decreased

- the maximum urinary flow (Qmax, ml/s) was increased

- the voiding time (VT, s) was decreased

This urodynamic profile is related to a lower risk of urologic complications, such as cystitis and bladder stones.

Erection

See also: Commons image gallery

An erection is the stiffening and rising of the penis, which occurs during sexual arousal, though it can also happen in non-sexual situations. Spontaneous erections frequently occur during adolescence due to friction with clothing, a full bladder or large intestine, hormone fluctuations, nervousness, and undressing in a nonsexual situation. It is also normal for erections to occur during sleep and upon waking. (See nocturnal penile tumescence.) The primary physiological mechanism that brings about erection is the autonomic dilation of arteries supplying blood to the penis, which allows more blood to fill the three spongy erectile tissue chambers in the penis, causing it to lengthen and stiffen. The now-engorged erectile tissue presses against and constricts the veins that carry blood away from the penis. More blood enters than leaves the penis until an equilibrium is reached where an equal volume of blood flows into the dilated arteries and out of the constricted veins; a constant erectile size is achieved at this equilibrium. The scrotum will usually tighten during erection.

Erection facilitates sexual intercourse though it is not essential for various other sexual activities.

Erection angle

Although many erect penises point upwards (see illustration), it is common and normal for the erect penis to point nearly vertically upwards or nearly vertically downwards or even horizontally straight forward, all depending on the tension of the suspensory ligament that holds it in position.

The following table shows how common various erection angles are for a standing male, out of a sample of 1,564 males aged 20 through 69. In the table, zero degrees is pointing straight up against the abdomen, 90 degrees is horizontal and pointing straight forward, while 180 degrees would be pointing straight down to the feet. An upward pointing angle is most common.[22]

| angle (°) from vertically upwards |

Percent of males |

|---|---|

| 0–30 | 4.9 |

| 30–60 | 29.6 |

| 60–85 | 30.9 |

| 85–95 | 9.9 |

| 95–120 | 19.8 |

| 120–180 | 4.9 |

Ejaculation

Ejaculation is the ejecting of semen from the penis, and is usually accompanied by orgasm. A series of muscular contractions delivers semen, containing male gametes known as sperm cells or spermatozoa, from the penis. It is usually the result of sexual stimulation, which may include prostate stimulation. Rarely, it is due to prostatic disease. Ejaculation may occur spontaneously during sleep (known as a nocturnal emission or wet dream). Anejaculation is the condition of being unable to ejaculate.

Ejaculation has two phases: emission and ejaculation proper. The emission phase of the ejaculatory reflex is under control of the sympathetic nervous system, while the ejaculatory phase is under control of a spinal reflex at the level of the spinal nerves S2–4 via the pudendal nerve. A refractory period succeeds the ejaculation, and sexual stimulation precedes it.[23]

Evolved adaptations

The human penis has been argued to have several evolutionary adaptations. The purpose of these adaptations is to maximise reproductive success and minimise sperm competition. Sperm competition is where the sperm of two males simultaneously resides within the reproductive tract of a female and they compete to fertilise the egg.[24] If sperm competition results in the rival male's sperm fertilising the egg, cuckoldry could occur. This is the process whereby males unwittingly invest their resources into offspring of another male and, evolutionarily speaking, should be avoided at all costs [25]

The most researched human penis adaptations are testis and penis size, ejaculate adjustment and semen displacement.[26]

Testis and penis size

Evolution has caused sexually selected adaptations to occur in penis and testis size in order to maximise reproductive success and minimise sperm competition.[27][28]

Sperm competition has caused the human penis to evolve in length and size for sperm retention and displacement.[28] To achieve this, the penis must be of sufficient length to reach any rival sperm and to maximally fill the vagina.[28] In order to ensure that the female retains the male's sperm, the adaptations in length of the human penis have occurred so that the ejaculate is placed close to the female cervix.[29] This is achieved when complete penetration occurs and the penis pushes against the cervix.[30] These adaptations have occurred in order to release and retain sperm to the highest point of the vaginal tract. As a result, this adaptation also leaves the male’s sperm less vulnerable to sperm displacement and semen loss. Another reason for this adaptation is due to the nature of the human posture, gravity creates vulnerability for semen loss. Therefore, a long penis, which places the ejaculate deep in the vaginal tract, could reduce the loss of semen.[31]

Another evolutionary theory of penis size is female mate choice and its associations with social judgements in modern-day society.[28][32] A study which illustrates female mate choice as an influence on penis size presented females with life-size, rotatable, computer generated males. These varied in height, body shape and flaccid penis size, with these aspects being examples of masculinity.[28] Female ratings of attractiveness for each male revealed that larger penises were associated with higher attractiveness ratings.[28] These relations between penis size and attractiveness have therefore led to frequently emphasized associations between masculinity and penis size in popular media.[32] This has led to a social bias existing around penis size with larger penises being preferred and having higher social status. This is reflected in the association between believed sexual prowess and male penis size and the social judgement of penis size in relation to 'manhood'.[32]

Like the penis, sperm competition has caused the human testicles to evolve in size through sexual selection.[27] This means that large testicles are an example of a sexually selected adaptation. The human testicles are moderately sized when compared to other animals such as gorillas and chimpanzees, placing somewhere midway.[33] Large testicles are advantageous in sperm competition due to their ability to produce a bigger ejaculation.[34] Research has shown that a positive correlation exists between the number of sperm ejaculated and testis size.[34] Larger testes have also been shown to predict higher sperm quality, including a larger number of motile sperm and higher sperm motility.[27]

Research has also demonstrated that evolutionary adaptations of testis size are dependent on the breeding system in which the species resides.[35] Single-male breeding systems - or monogamous societies - tend to show smaller testis size than do multi-male breeding systems or extra pair copulation (EPC) societies. Human males live largely in monogamous societies like gorillas, and therefore testis size is smaller in comparison to primates in multi-male breeding systems, such as chimpanzees. The reason for the differentiation in testis size is that in order to succeed reproductively in a multi-male breeding system, males must possess the ability to produce several fully fertilising ejaculations one after another.[27] This, however, is not the case in monogamous societies, where a reduction in fertilising ejaculations has no effect on reproductive success.[27] This is reflected in humans, as the sperm count in ejaculations is decreased if copulation occurs more than 3 to 5 times in a week.[36]

Ejaculate adjustment

One of the primary ways in which a male's ejaculate has evolved to overcome sperm competition is through the speed at which it travels. Ejaculates can travel up to 30-60 centimetres at a time which, when combined with its placement at the highest point of the vaginal tract, acts to increase a male's chances that an egg will be fertilised by his sperm (as opposed to a potential rival male's sperm), thus maximising his paternal certainty.[31]

In addition, males can - and do - adjust their ejaculates in response to sperm competition and according to the likely cost-benefits of mating with a particular female.[37] Research has focused primarily on two fundamental ways in which males go about achieving this: adjusting ejaculate size and adjusting ejaculate quality.

Ejaculate size

The number of sperm in any given ejaculate varies from one ejaculate to another.[38] This variation is hypothesised to be a male's attempt to eliminate, if not reduce, his sperm competition. A male will alter the number of sperm he inseminates into a female according to his perceived level of sperm competition,[26] inseminating a higher number of sperm if he suspects a greater level of competition from other males.

In support of ejaculate adjustment, research has shown that a male typically increases the amount he inseminates sperm into his partner after they have been separated for a period of time.[39] This is largely due to the fact that the less time a couple is able to spend together, the chances the female will be inseminated by another male increases,[40] hence greater sperm competition. Increasing the number of sperm a male inseminates into a female acts to get rid of any rival male's sperm that may be stored within the female, as a result of her potential extra-pair copulations (EPCs) during this separation. Through increasing the amount he inseminates his partner following separation, a male increases his chances of paternal certainty. This increase in the number of sperm a male produces in response to sperm competition is not observed for masturbatory ejaculates.[26]

Ejaculate quality

Males also adjust their ejaculates in response to sperm competition in terms of quality. Research has demonstrated, for example, that simply viewing a sexually explicit image of a female and two males (i.e. high sperm competition) can cause males to produce a greater amount of motile sperm than when viewing a sexually explicit image depicting exclusively three females (i.e. low sperm competition).[41] Much like increasing the number, increasing the quality of sperm that a male inseminates into a female enhances his paternal certainty when the threat of sperm competition is high.

Ejaculate adjustment and female quality

A female's phenotypic quality is a key determinant of a male's ejaculate investment.[42] Research has shown that males produce larger ejaculates containing better, more motile sperm when mating with a higher quality female.[37] This is largely to reduce a male's sperm competition, since more attractive females are likely to be approached and subsequently inseminated by more males than are less attractive females. Increasing investment in females with high quality phenotypic traits therefore acts to offset the ejaculate investment of others.[42] In addition, female attractiveness has been shown to be an indicator of reproductive quality, with greater value in higher quality females.[43] It is therefore beneficial for males to increase their ejaculate size and quality when mating with more attractive females, since this is likely to maximise their reproductive success also. Through assessing a female's phenotypic quality, males can judge whether or not to invest (or invest more) in a particular female, which will influence their subsequent ejaculate adjustment.

Semen displacement

The shape of the human penis is thought to have evolved as a result of sperm competition.[44] Semen displacement is an adaptation of the shape of the penis to draw foreign semen away from the cervix. This means that in the event of a rival male's sperm residing within the reproductive tract of a female, the human penis is able to displace the rival sperm, replacing it with his own.[45]

Semen displacement has two main benefits for a male. Firstly, by displacing a rival male's sperm, the risk of the rival sperm fertilising the egg is reduced, thus minimising the risk of sperm competition.[46] Secondly, the male replaces the rival's sperm with his own, therefore increasing his own chance of fertilising the egg and successfully reproducing with the female. However, males have to ensure they do not displace their own sperm. It is thought that the relatively quick loss of erection after ejaculation, penile hypersensitivity following ejaculation, and the shallower, slower thrusting of the male after ejaculation, prevents this from occurring.[47]

The coronal ridge is the part of the human penis thought to have evolved to allow for semen displacement. Research has studied how much semen is displaced by different shaped, artificial genitals.[48] This research showed that, when combined with thrusting, the coronal ridge of the penis is able to remove the seminal fluid of a rival male from within the female reproductive tract. It does this by forcing the semen under the frenulum of the coronal ridge, causing it to collect behind the coronal ridge shaft.[48] When model penises without a coronal ridge were used, less than half the artificial sperm was displaced, compared to penises with a coronal ridge.[48]

The presence of a coronal ridge alone, however, is not sufficient for effective semen displacement. It must be combined with adequate thrusting to be successful. It has been shown that the deeper the thrusting, the larger the semen displacement. No semen displacement occurs with shallow thrusting.[48] Some have therefore termed thrusting as a semen displacement behaviour.[49]

The behaviours associated with semen displacement, namely thrusting (number of thrusts and depth of thrusts), and duration of sexual intercourse,[49] have been shown to vary according to whether a male perceives the risk of partner infidelity to be high or not. Males and females report greater semen displacement behaviours following allegations of infidelity. In particular, following allegations of infidelity, males and females report deeper and quicker thrusting during sexual intercourse.[48]

Circumcision has been suggested to affect semen displacement. Circumcision causes the coronal ridge to be more pronounced, and it has been hypothesised that this could enhance semen displacement.[31] This is supported by females' reports of sexual intercourse with circumcised males. Females report that their vaginal secretions diminish as intercourse with a circumcised male progresses, and that circumcised males thrust more deeply.[50] It has therefore been suggested that the more pronounced coronal ridge, combined with the deeper thrusting, causes the vaginal secretions of the female to be displaced in the same way as rival sperm can be.[31]

Clinical significance

Disorders

- Paraphimosis is an inability to move the foreskin forward over the glans. It can result from fluid trapped in a foreskin left retracted, perhaps following a medical procedure, or accumulation of fluid in the foreskin because of friction during vigorous sexual activity.

- In Peyronie's disease, anomalous scar tissue grows in the soft tissue of the penis, causing curvature. Severe cases can be improved by surgical correction.

- A thrombosis can occur during periods of frequent and prolonged sexual activity, especially fellatio. It is usually harmless and self-corrects within a few weeks.

- Infection with the herpes virus can occur after sexual contact with an infected carrier; this may lead to the development of herpes sores.

- Pudendal nerve entrapment is a condition characterized by pain on sitting and the loss of penile sensation and orgasm. Occasionally there is a total loss of sensation and orgasm. The pudendal nerve can be damaged by narrow, hard bicycle seats and accidents. This can also occur in the clitoris of females.

- Penile fracture can occur if the erect penis is bent excessively. A popping or cracking sound and pain is normally associated with this event. Emergency medical assistance should be obtained as soon as possible. Prompt medical attention lowers the likelihood of permanent penile curvature.

- In diabetes, peripheral neuropathy can cause tingling in the penile skin and possibly reduced or completely absent sensation. The reduced sensations can lead to injuries for either partner and their absence can make it impossible to have sexual pleasure through stimulation of the penis. Since the problems are caused by permanent nerve damage, preventive treatment through good control of the diabetes is the primary treatment. Some limited recovery may be possible through improved diabetes control.

- Erectile dysfunction is the inability to develop and maintain an erection sufficiently firm for satisfactory sexual performance. Diabetes is a leading cause, as is natural aging. A variety of treatments exist, most notably including the phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor drugs (such as sildenafil citrate, marketed as Viagra), which work by vasodilation.

- Priapism is a painful and potentially harmful medical condition in which the erect penis does not return to its flaccid state. Priapism lasting over four hours is a medical emergency. The causative mechanisms are poorly understood but involve complex neurological and vascular factors. Potential complications include ischaemia, thrombosis, and impotence. In serious cases the condition may result in gangrene, which may result in amputation. However, that is usually only the case if the organ is broke out and injured because of it. The condition has been associated with a variety of drugs including prostaglandin. Contrary to common knowledge, sildenafil (Viagra) will not cause it.[51]

- Lymphangiosclerosis is a hardened lymph vessel, although it can feel like a hardened, almost calcified or fibrous, vein. It tends not to share the common blue tint with a vein however. It can be felt as a hardened lump or "vein" even when the penis is flaccid, and is even more prominent during an erection. It is considered a benign physical condition. It is fairly common and can follow a particularly vigorous sexual activity for men, and tends to go away if given rest and more gentle care, for example by use of lubricants.

- Carcinoma of the penis is rare with a reported rate of 1 person in 100,000 in developed countries. Some sources state that circumcision can protect against this disease, but this notion remains controversial among medical circles.[52]

Developmental disorders

- Hypospadias is a developmental disorder where the meatus is positioned wrongly at birth. Hypospadias can also occur iatrogenically by the downward pressure of an indwelling urethral catheter.[53] It is usually corrected by surgery.

- A micropenis is a very small penis caused by developmental or congenital problems.

- Diphallia, or penile duplication (PD), is the condition of having two penises. However, this disorder is extremely rare.

Alleged and observed psychological disorders

- Penis panic (koro in Malaysian/Indonesian)—delusion of shrinkage of the penis and retraction into the body. This appears to be culturally conditioned and largely limited to Ghana, Sudan, China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and West Africa.

- In April 2008, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo, West Africa's 'Police arrested 14 suspected victims (of penis snatching) and sorcerers accused of using black magic or witchcraft to steal (make disappear) or shrink men's penises to extort cash for cure, amid a wave of panic. Arrests were made in an effort to avoid bloodshed seen in Ghana a decade before, when 12 penis snatchers were beaten to death by mobs.[54]

- Penis envy – the contested Freudian belief of all women inherently envying men for having penises.

Surgical replacement

The first successful penis allotransplant surgery was done in September 2005 in a military hospital in Guangzhou, China.[55] A man at 44 sustained an injury after an accident and his penis was severed; urination became difficult as his urethra was partly blocked. A recently brain-dead man, aged 23, was selected for the transplant. Despite atrophy of blood vessels and nerves, the arteries, veins, nerves and the corpora spongiosa were successfully matched. But, on 19 September (after two weeks), the surgery was reversed because of a severe psychological problem (rejection) by the recipient and his wife.[56]

In 2009, researchers Chen, Eberli, Yoo and Atala have produced bioengineered penises and implanted them on rabbits.[57] The animals were able to obtain erection and copulate, with 10 of 12 rabbits achieving ejaculation. This study shows that in the future it could be possible to produce artificial penises for replacement surgeries or phalloplasties.

In 2015 the world's first successful penis transplant took place in Cape Town, South Africa in a nine-hour operation performed by surgeons from Stellenbosch University and Tygerberg Hospital. The 21-year-old recipient, who had been sexually active, had lost his penis in a botched circumcision at 18.[58]

An Italian nonprofit known as Foregen is working on regrowing the foreskin, with the procedure potentially being partially surgical.[59]

Society and culture

Terminology

In many cultures, referring to the penis is taboo or vulgar, and a variety of slang words and euphemisms are used to talk about it. In English, these include 'member', 'dick', 'cock', 'prick', 'dork', 'peter', 'pecker', 'putz', 'stick', 'rod', 'thing', 'banana', 'dong', 'schmuck' and 'schlong' and 'todger'.[60] Many of these (especially 'dick', 'cock', 'prick', 'dork', 'putz', and 'schmuck') are used as insults—though sometimes playfully--, meaning an unpleasant or unworthy person.[61][62] Among these, historically, most commonly used euphemism for penis in English literature and society was 'member'.[63]

- Aesthetic, e.g., Body modification

- In humor, considered indecent or completely taboo in various cultures

- Religious veneration, see St. Priapus Church[64]

- In symbology, e.g., Phallus

- In architecture and sculpture, Phallic architecture

Alteration

The penis is sometimes pierced or decorated by other body art. Other than circumcision, genital alterations are almost universally elective and usually for the purpose of aesthetics or increased sensitivity. Piercings of the penis include the Prince Albert, the apadravya, the ampallang, the dydoe, and the frenum piercing. Foreskin restoration or stretching is a further form of body modification, as well as implants under the shaft of the penis.

Male to female transsexuals who undergo sex reassignment surgery, have their penis surgically modified into a neovagina. Female to male transsexuals may have a phalloplasty.

Other practices that alter the penis are also performed, although they are rare in Western societies without a diagnosed medical condition. Apart from a penectomy, perhaps the most radical of these is subincision, in which the urethra is split along the underside of the penis. Subincision originated among Australian Aborigines, although it is now done by some in the U.S. and Europe.

Penis removal is another form of alteration done to the penis.

Circumcision

The most common form of genital alteration is circumcision: removal of part or all of the foreskin for various cultural, religious, and more rarely medical reasons. For infant circumcision, modern devices such as the Gomco clamp, Plastibell, and Mogen clamp are available.[65]

With all modern devices the same basic procedure is followed. First, the amount of foreskin to be removed is estimated. The foreskin is then opened via the preputial orifice to reveal the glans underneath and ensured that it is normal. The inner lining of the foreskin (preputial epithelium) is then separated from its attachment to the glans. The device is then placed (this sometimes requires a dorsal slit) and remains there until blood flow has stopped. Finally, part, or all, of the foreskin is then removed.

Adult circumcisions are often performed without clamps and require 4 to 6 weeks of abstinence from masturbation or intercourse after the operation to allow the wound to heal.[66] In some African countries, male circumcision is often performed by non-medical personnel under non-sterile conditions.[67] After hospital circumcision, the foreskin may be used in biomedical research,[68] consumer skin-care products,[69] skin grafts,[70][71][72] or β-interferon-based drugs.[73] In parts of Africa, the foreskin may be dipped in brandy and eaten by the patient, eaten by the circumciser, or fed to animals.[74] According to Jewish law, after a Brit milah, the foreskin should be buried.[75]

There is controversy surrounding circumcision. Advocates of circumcision argue, for example, that it provides important health advantages that outweigh the risks, has no substantial effects on sexual function, has a low complication rate when carried out by an experienced physician, and is best performed during the neonatal period.[76] Opponents of circumcision argue, for example, that the practice has been and is still defended through the use of various myths; that it interferes with normal sexual function; that it is extremely painful; and that when performed on infants and children, it violates the individual's human rights.[77]

The American Medical Association stated in 1999: "Virtually all current policy statements from specialty societies and medical organizations do not recommend routine neonatal circumcision, and support the provision of accurate and unbiased information to parents to inform their choice."[78]

The World Health Organization (WHO; 2007), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS; 2007), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; 2008) state that evidence indicates male circumcision significantly reduces the risk of HIV acquisition by men during penile-vaginal sex, but also state that circumcision only provides partial protection and should not replace other interventions to prevent transmission of HIV.[79][80] In addition, some doctors have expressed concern over the policy and the data that supports it.[81][82]

Additional images

Dissection showing the fascia of the penis as well as several surrounding structures.

Dissection showing the fascia of the penis as well as several surrounding structures. Image showing innervation and blood-supply of the human male external genitalia.

Image showing innervation and blood-supply of the human male external genitalia.

References

- 1 2 3 Keith L. Moore, T. V. N. Persaud, Mark G. Torchia, The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology 10th Ed. Elsevier Health Sciences, 2015 ISBN 9780323313483, pp 267-69

- ↑ Richard E. Jones; Kristin H. Lopez (28 September 2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0.

- ↑ Video of gliding action

- ↑ Wessells H, Lue TF, McAninch JW (September 1996). "Penile length in the flaccid and erect states: guidelines for penile augmentation". The Journal of Urology. 156 (3): 995–7. PMID 8709382. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65682-9.

- ↑ Chen J, Gefen A, Greenstein A, Matzkin H, Elad D (December 2000). "Predicting penile size during erection". International Journal of Impotence Research. 12 (6): 328–33. PMID 11416836. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900627.

- ↑ "ANSELL RESEARCH – The Penis Size Survey". March 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-07-01. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- ↑ "Penis Size FAQ & Bibliography". Kinsey Institute. 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Dixson, A. F. (2009). Sexual selection and the origins of human mating systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 61–65.

- ↑ Center of Disease Control. "DES Update: Consumers". Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Swan SH, Main KM, Liu F, et al. (August 2005). "Decrease in anogenital distance among male infants with prenatal phthalate exposure". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (8): 1056–61. PMC 1280349

. PMID 16079079. doi:10.1289/ehp.8100.

. PMID 16079079. doi:10.1289/ehp.8100. - ↑ Montague, Peter. "PCBs Diminish Penis Size". Rachel's Hazardous Waste News. 372. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03.

- ↑ "Hormone Hell". DISCOVER. Retrieved 2008-04-05.

- ↑ Dickinson, R.L. (1940). The Sex Life of the Unmarried Adult. New York: Vanguard Press.

- ↑ Brown, Clarence William (February 13, 2014). "Pearly Penile Papules: Epidemiology". Medscape. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "Spots on the penis". 3 November 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Richard E. Jones; Kristin H. Lopez (28 September 2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-382185-0.

- ↑ Ponchietti R, Mondaini N, Bonafè M, Di Loro F, Biscioni S, Masieri L (February 2001). "Penile length and circumference: a study on 3,300 young Italian males". European Urology. 39 (2): 183–6. PMID 11223678. doi:10.1159/000052434.

- ↑ Sie JA, Blok BF, de Weerd H, Holstege G (2001). "Ultrastructural evidence for direct projections from the pontine micturition center to glycine-immunoreactive neurons in the sacral dorsal gray commissure in the cat". J. Comp. Neurol. 429 (4): 631–7. PMID 11135240. doi:10.1002/1096-9861(20010122)429:4<631::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-M.

- ↑ Schirren, C.; Rehacek, M.; Cooman, S. de; Widmann, H.-U. (24 April 2009). "Die retrograde Ejakulation". Andrologia. 5 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0272.1973.tb00878.x.

- ↑ Y. de Jong; R.M. ten Brinck; J.H.F.M. Pinckaers; A.A.B. Lycklama à Nijeholt. "Influence of voiding posture on urodynamic parameters in men: a literature review" (PDF). Nederlands Tijdschrift voor urologie). Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ de Jong, Y; Pinckaers, JH; Ten Brinck, RM; Lycklama À Nijeholt, AA; Dekkers, OM (2014). "Urinating Standing versus Sitting: Position Is of Influence in Men with Prostate Enlargement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.". PLOS ONE. 9 (7): e101320. PMC 4106761

. PMID 25051345. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320.

. PMID 25051345. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101320. - ↑ Sparling J (1997). "Penile erections: shape, angle, and length". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 23 (3): 195–207. PMID 9292834. doi:10.1080/00926239708403924.

- ↑ Carlson, Neil. (2013). Physiology of Behavior. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

- ↑ Bleske-Rechek, A. L.; Euler, H. A.; LeBlanc, G. J.; Shackelford, T. K.; Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. (2002). "Psychological adaptation to human sperm competition." (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior.

- ↑ Ehrke, A. D.; Pham, M. N.; Shackelford, T. K.; Welling, L. L. M. (2013). "Oral sex, semen displacement, and sexual arousal: testing the ejaculate adjustment hypothesis.". Evolutionary Psychology.

- 1 2 3 Shackelford, Todd K.; Goetz, Aaron T. (2007-02-01). "Adaptation to Sperm Competition in Humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (1): 47–50. ISSN 0963-7214. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moller, A. P. (1988). "Ejaculate quality, testes size and sperm competition in primates". Journal of Human Evolution. 17: 479–488. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(88)90037-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mautz, B. S.; Wong, B. B. M.; Peters, R. A.; Jennions, M. D. (April 23, 2013). "Penis size interacts with body shape and height to influence male attractiveness". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (17): 6925–30. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.6925M. JSTOR 42590540. PMC 3637716

. PMID 23569234. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219361110.

. PMID 23569234. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219361110. - ↑ Masters, W. H.; Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- ↑ Schultz, W. W.; van Andel, P.; Sabelis, I.; Mooyaart, E. (December 18, 1999). "Magnetic resonance imaging of male and female genitals during coitus and female sexual arousal" (PDF). BMJ. 319: 1596–600. PMC 28302

. PMID 10600954. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1596.

. PMID 10600954. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1596. - 1 2 3 4 Gallup, G. G.; Burch, R. L. (January 1, 2004). "Semen displacement as a sperm competition strategy in humans" (PDF). Evolutionary Psychology. 2. doi:10.1177/147470490400200105.

- 1 2 3 Lever, J.; Frederick, D. A.; Peplau, L. A. (2006). "Does size matter? Men's and women's views on penis size across the lifespan". Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 7: 129–143. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.7.3.129.

- ↑ Harcourt, A. H.; Purvis, A.; Liles, L. (1995). "Sperm competition: Mating system, not breeding season, affects testes size of primates". Functional Ecology. 9 (3): 469–476. JSTOR 2390011. doi:10.2307/2390011.

- 1 2 Simmons, Leigh W.; Firman, Renée C.; Rhodes, Gillian; Peters, Marianne (2003). "Human sperm competition: testis size, sperm production and rates of extra pair copulations". Animal Behaviour. 68: 297–302. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.11.013.

- ↑ Harcourt, A. H.; Harvey, P. H.; Larson, S. G.; Short, R. V. (1981). "Testis weight, body weight and breeding system in primates". Nature. 293 (5827): 55–57. Bibcode:1981Natur.293...55H. PMID 7266658. doi:10.1038/293055a0.

- ↑ Freund, M. (1962). "Interrelationships among the characteristics of human semen and facts affecting semen specimen quality". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 4: 143–159. PMID 13959612. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0040143.

- 1 2 Kelly, Clint D.; Jennions, Michael D. (2011-11-01). "Sexual selection and sperm quantity: meta-analyses of strategic ejaculation". Biological Reviews. 86 (4): 863–884. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 21414127. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00175.x.

- ↑ Shackelford, Todd K.; Pound, Nicholas; Goetz, Aaron T. (2005). "Psychological and Physiological Adaptations to Sperm Competition in Humans". Review of General Psychology. 9 (3): 228–248. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.228.

- ↑ Baker, R. Robin; Bellis, Mark A. (1989-05-01). "Number of sperm in human ejaculates varies in accordance with sperm competition theory". Animal Behaviour. 37 (Pt 5): 867–869. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(89)90075-4.

- ↑ Shackelford, T (2002). "Psychological adaptation to human sperm competition". Evolution and Human Behavior. 23 (2): 123–138. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(01)00090-3.

- ↑ Kilgallon, Sarah J.; Simmons, Leigh W. (2005-09-22). "Image content influences men's semen quality". Biology Letters. 1 (3): 253–255. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1617155

. PMID 17148180. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0324.

. PMID 17148180. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0324. - 1 2 Leivers, Samantha; Rhodes, Gillian; Simmons, Leigh W. (2014-09-01). "Context-dependent relationship between a composite measure of men’s mate value and ejaculate quality". Behavioral Ecology. 25 (5): 1115–1122. ISSN 1045-2249. doi:10.1093/beheco/aru093.

- ↑ Thornhill, Randy; Gangestad, Steven W. (2008). The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199712489.

- ↑ Shackelford, Todd K.; Goetz, Aaron T. (2007-02-01). "Adaptation to Sperm Competition in Humans". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 16 (1): 47–50. ISSN 0963-7214. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00473.x.

- ↑ Burch, R. L.; Gallup, G. G.; Mitchell, T. J. (2006). "Semen displacement as a sperm competition strategy: Multiple mating, self-semen displacement, and timing of in-pair copulations". Human Nature.

- ↑ Burch, R. L.; Gallup, G. G.; Parvez, R. A.; Stockwell, M. L.; Zappieri, M. L. (2003). "The human penis as a semen displacement device.". Evolution and Behaviour. 24: 277–289.

- ↑ Burch, R. L.; Gallup, G. G.; Mitchell, T. J. (2006). "Semen displacement as a sperm competition strategy: Multiple mating, self-semen displacement, and timing of in-pair copulations". Human Nature. 17: 253–264.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Burch, R. L.; Davis, J. A.; Gallup, G. G.; Parvez, R. A.; Stockwell, M. L.; Zappieri, M. L. (2003). "The human penis as a semen displacement device." (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior.

- 1 2 Euler, H. A.; Goetz, A. T.; Hoier, S.; Shackelford, T. K.; Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. (2005). "Mate retention, semen displacement, and human sperm competition: A preliminary investigation of tactics to prevent and correct female infidelity." (PDF). Personality and Individual Differences. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2004.05.028.

- ↑ O'Hara, K.; O'Hara, J. (1999). "The effect of male circumcision on the sexual enjoyment of the female partner.". British Journal of Urology.

- ↑ Goldenberg MM (1998). "Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate in the treatment of male erectile dysfunction". Clinical Therapeutics. 20 (6): 1033–48. PMID 9916601. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(98)80103-3.

- ↑ Boczko S, Freed S (November 1979). "Penile carcinoma in circumcised males". New York State Journal of Medicine. 79 (12): 1903–4. PMID 292845.

- ↑ Andrews HO, Nauth-Misir R, Shah PJ (March 1998). "Iatrogenic hypospadias—a preventable injury?". Spinal Cord. 36 (3): 177–80. PMID 9554017. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3100508.

- ↑ "Lynchings in Congo as penis theft panic hits capital". 22 April 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017 – via Reuters.

- ↑ "世界首例异体阴茎移植成功 40岁患者数周后出院·广东新闻·珠江三角洲·南方新闻网". Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (2006-09-18). "Man rejects first penis transplant". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ Chen KL, Eberli D, Yoo JJ, Atala A (November 2009). "Regenerative Medicine Special Feature: Bioengineered corporal tissue for structural and functional restoration of the penis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (8): 3346–50. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.3346C. PMC 2840474

. PMID 19915140. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909367106.

. PMID 19915140. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909367106. - ↑ Gallagher, James (13 March 2015). "South Africans perform first 'successful' penis transplant". Retrieved 16 January 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- ↑ "How One Company Aims to Help Circumcised Men Grow Their Foreskin Back". Motherboard. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- ↑ "todger - Definition, meaning & more - Collins Dictionary". Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ↑ Marv Rubinstein, American English Compendium: A Portable Guide to the Idiosyncrasies, Subtleties, Technical Lingo, and Nooks and Crannies of American English, ISBN 1442232838, p. 147

- ↑ Ruth Bell, Changing Bodies, Changing Lives: Expanded Third Edition: A Book for Teens on Sex and Relationships, ISBN 0307794067, p. 15

- ↑ David M. Friedman 2008.

- ↑ Fritscher, Jack; Anton Szandor La Vey (2004). Popular witchcraft: straight from the witch's mouth. Popular Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-299-20304-7. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Holman JR, Lewis EL, Ringler RL (August 1995). "Neonatal circumcision techniques". American Family Physician. 52 (2): 511–8, 519–20. PMID 7625325.

- ↑ Holman JR, Stuessi KA (March 1999). "Adult circumcision". American Family Physician. 59 (6): 1514–8. PMID 10193593.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (2007-02-27). "In Africa, a problem with circumcision and AIDS". The New York Times.

- ↑ Hovatta O, Mikkola M, Gertow K, et al. (July 2003). "A culture system using human foreskin fibroblasts as feeder cells allows production of human embryonic stem cells". Human Reproduction. 18 (7): 1404–9. PMID 12832363. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg290.

- ↑ "'Miracle' Wrinkle Cream's Key Ingredient". Banderasnews.com. Banderas News, Inc. April 2008. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ↑ "High-Tech Skinny on Skin Grafts". www.wired.com:science:discoveries. CondéNet, Inc. 1999-02-16. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ "Skin Grafting". www.emedicine.com. WebMD. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Amst, Catherine; Carey, John (July 27, 1998). "Biotech Bodies". www.businessweek.com. The McGraw-Hill Companies Inc. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Cowan, Alison Leigh (April 19, 1992). "Wall Street; A Swiss Firm Makes Babies Its Bet". New York Times:Business. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Anonymous (editorial) (1949-12-24). "A ritual operation". British Medical Journal. 2 (4642): 1458–1459. PMC 2051965

. PMID 20787713. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1458.

. PMID 20787713. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1458. ...in parts of West Africa, where the operation is performed at about 8 years of age, the prepuce is dipped in brandy and eaten by the patient; in other districts the operator is enjoined to consume the fruits of his handiwork, and yet a further practice, in Madagascar, is to wrap the operation specifically in a banana leaf and feed it to a calf.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh Deah, 265:10

- ↑ Schoen EJ (December 2007). "Should newborns be circumcised? Yes". Canadian Family Physician. 53 (12): 2096–8, 2100–2. PMC 2231533

. PMID 18077736.

. PMID 18077736. - ↑ Milos MF, Macris D (1992). "Circumcision. A medical or a human rights issue?". Journal of Nurse-midwifery. 37 (2 Suppl): 87S–96S. PMID 1573462. doi:10.1016/0091-2182(92)90012-R.

- ↑ "Report 10 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (I-99):Neonatal Circumcision". 1999 AMA Interim Meeting: Summaries and Recommendations of Council on Scientific Affairs Reports. American Medical Association. December 1999. p. 17. Archived from the original on December 12, 2004. Retrieved 2006-06-13.

- ↑ "New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ "Male Circumcision and Risk for HIV Transmission and Other Health Conditions: Implications for the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2008. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ G. Dowsett; M. Couch. "Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Is There Really Enough of the Right Kind of Evidence?". Reproductive Health Matters. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ Vardi Y, Sadeghi-Nejad H, Pollack S, Aisuodionoe-Shadrach OI, Sharlip ID (July 2007). "Male circumcision and HIV prevention". J Sex Med. 4 (4 Pt 1): 838–43. PMID 17627731. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00511.x.

Bibliography

- David M. Friedman (4 September 2008), A Mind of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis, Simon and Schuster, p. 43, ISBN 978-1-43-913608-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Human penis. |