Great white pelican

| Great white pelican | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Pelecaniformes |

| Family: | Pelecanidae |

| Genus: | Pelecanus |

| Species: | P. onocrotalus |

| Binomial name | |

| Pelecanus onocrotalus Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

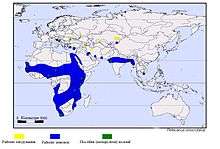

| yellow : nonbreeding area blue : breeding area green : year-round area | |

The great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus) also known as the eastern white pelican, rosy pelican or white pelican is a bird in the pelican family.[2] It breeds from southeastern Europe through Asia and in Africa in swamps and shallow lakes.

Description

The great white pelican is a huge bird, with only the Dalmatian pelican averaging larger amongst the pelicans. It measures 140 to 180 cm (55 to 71 in) in length with a 28.9 to 47.1 cm (11.4 to 18.5 in) enormous pink and yellow bill, and a bright yellow to orange gular pouch.[3][4][5][6] The wingspan measures 226 to 360 cm (7.41 to 11.81 ft), with the latter measurement being the largest recorded among extant flying animals outside of the great albatross.[7][8][3] Adult males weigh from 9 to 15 kg (20 to 33 lb), and larger races from the Palaearctic are usually around 11 kg (24 lb), with few exceeding 13 kg (29 lb).[9] Females are considerably less bulkier, weighing 5.4 to 9 kg (12 to 20 lb).[3] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 60 to 73 cm (24 to 29 in), the tail is 16 to 21 cm (6.3 to 8.3 in) and the tarsus is 13 to 14.9 cm (5.1 to 5.9 in) long. The standard measurements from different areas indicate that pelicans from the Western Palaearctic are somewhat larger in size than the ones from Asia and Africa. The male has a downward bend in the neck and the female has a shorter, straighter beak. The plumage is predominantly white, and pinkish skin surrounds the bare, dark eyes.[6][10] It has fleshy-yellow legs and pointed forehead-feathers where meeting culmen.[10] In breeding season, the male has pinkish skin while the female has orangey skin on its face.[11] The white plumage becomes tinged-pink with a yellow patch on the breast,[6] and the body is tinged with yellowish-rosy.[10] It also has a short, shaggy crest on the nape.[10] In flight, it is an elegant soaring bird, with the head held close to and aligned with the body. Its flight consists of a few slow wingbeats followed by a glide.[10] The white covert feathers contrast with the solid black primary and secondary feathers.[5]

It differs from the Dalmatian pelican by its pure white, rather than greyish-white, plumage, a bare pink facial patch around the eye, and pinkish legs.[12] The spot-billed pelican of Asia is slightly smaller than the great white, with greyish tinged white plumage, and a paler, duller-colored bill.[6] Similarly, the pink-backed pelican is smaller, with brownish-grey plumage, a light pink to off-grey bill, and a pinkish wash on the back.[3]

The juvenile has darker, greyish-brown underparts and dark flight feathers,[10] with brown edges to wings.[13] The head, neck, and upperparts, including upperwing coverts, are mostly brown, and the pouch is grey.[14] It has a whitish forehead, rump, and tail, and the grey legs and feet.[13]

It is mostly silent, and has a variety of low-pitched lowing, grunting, and growling calls. The flight call is a deep, quiet croak.[12] At breeding colonies, it gives geep moooo calls.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The breeding range of the great white pelican extends to Ethiopia, Tanzania, Chad, northern Cameroons, and Nigeria in Africa, and has been observed or reported breeding in Zambia, Botswana, and South Africa.[15] In the 1990s, 6,700 to 11,000 breeding pairs in 23 to 25 breeding sites, were found in the Palearctic region.[16] About 3,070 to 4,300 pairs are present in the Soviet Union.[17] Only two breeding colonies are located in the Mediterranean basin, one having 250 to 400 pairs in Turkey and the other having 50 to 100 pairs in northern Greece.[16] The breeding colony at Lake Rukwa, Tanzania is the largest known breeding colony in Africa, followed by the Lake Shala, Ethiopia colony which is probably of crucial importance to the species in Africa.[15]

The African population of about 75,000 pairs of the great white pelican is resident.[16] The ones breeding in the Palearctic region are migrants, although it is possible that the majority of the western Palearctic populations stop-over in Israel during their autumn migration.[18] The migration routes are only partially known.[16] Migratory populations are found from Eastern Europe to Kazakhstan during the breeding season. More than 50% of Eurasian great white pelicans breed in the Danube Delta in Romania. They also prefer staying in the Lakes near Burgas, Bulgaria and in Srebarna Lake in Bulgaria. The pelicans arrive in the Danube in late March or early April and depart after breeding from September to late November.[3] Wintering locations for European pelicans are not exactly known but wintering birds may occur in northeastern Africa through Iraq to north India, with a particularly large number of breeders from Asia wintering around Pakistan and Sri Lanka.[3] Northern populations migrate to China, India, Myanmar, with stragglers reaching Java and Bali in Indonesia.[19] These are birds that are found mostly in lowlands, though in East Africa and Nepal may be found living at elevations of up to 1,372 m (4,501 ft).[3]

Overall, the great white pelican is one of the most widely distributed species. Although some areas still hold quite large colonies, it ranks behind the brown pelican and possibly the Australian pelican in overall abundance.[3] Europe now holds an estimated 7,345–10,000 breeding pairs, with over 4,000 pairs that are known to nest in Russia. During migration, more than 75,000 have been observed in Israel and, in winter, over 45,000 may stay in Pakistan. In all its colonies combined, 75,000 pairs are estimated to nest in Africa.[3] It is possibly extinct in Serbia and Montenegro, and regionally extinct in Hungary.[1]

Great white pelicans usually prefer shallow, (seasonally or tropical) warm fresh water. Well scattered groups of breeding pelicans occur through Eurasia from the eastern Mediterranean to Vietnam.[3] In Eurasia, fresh or brackish waters may be inhabited and the pelicans may be found in lakes, deltas, lagoons and marshes, usually with dense reed beds nearby for nesting purposes.[3] Additionally, sedentary populations are found year-round in Africa, south of the Sahara Desert although these are patchy. In Africa, great white pelicans occur mainly around freshwater and alkaline lakes and may also be found in coastal, estuarine areas.[20] Beyond reed beds, African pelicans have nested on inselbergs and flat inshore islands off of Banc d'Arguin National Park.[3]

Behavior

The great white pelican is highly sociable and often forms large flocks.[12] It is well adapted for aquatic life. The short strong legs and webbed feet propel it in water and aid the rather awkward takeoff from the water surface. Once aloft, the long-winged pelicans are powerful fliers, however, and often travel in spectacular linear, circular, or V-formation groups.[10]

Feeding

The great white pelican mainly eats fish.[1] It leaves its roost to feed early in the morning and may fly over 100 km (62 mi) in search of food, as has been observed in Chad and Mogode, Cameroon.[3] It needs from 0.9 to 1.4 kg (2.0 to 3.1 lb) of fish every day.[3] This corresponds to around 28,000,000 kg (62,000,000 lb) of fish consumption every year at the largest colony of the great white pelican, on Tanzania's Lake Rukwa, with almost 75,000 birds. Fish targeted are usually fairly large ones, in the 500–600 g (1.1–1.3 lb) weight range, and are taken based on regional abundance.[3] Common carp are preferred in Europe, mullets in China, and Arabian toothcarp in India.[3] In Africa, often the commonest cichlids, including many species in the Haplochromis and Tilapia genera, seem to be preferred.[3]

The pelican's pouch serves simply as a scoop. As the pelican pushes its bill underwater, the lower bill bows out, creating a large pouch which fills with water and fish. As it lifts its head, the pouch contracts, forcing out the water but retaining the fish. A group of 6 to 8 great white pelicans gather in a horseshoe formation in water to feed together. They dip their bills in unison, creating a circle of open pouches, ready to trap every fish in the area. Most feeding is cooperative and done in groups, especially in shallow waters where fish schools can be corralled easily, though they may also forage alone as well.[3]

Great white pelicans are not restricted to fish, however, and are often opportunistic foragers. In some situations, they eat chicks of other birds, such as the well documented case off the southwest coast of South Africa.[21] Here, breeding pelicans from the Dassen Island predate chicks weighing up to 2 kg (4.4 lb) from the Cape gannet colony on Malgas Island.[22] Similarly, in Walvis Bay, Namibia the eggs and chicks of Cape cormorants are fed regularly to young pelicans. The local pelican population is so reliant on the cormorants, that when the cormorant species experienced a population decline, the numbers of pelicans appeared to decline as well.[3]

They also rob other birds of their prey. During periods of starvation, they also eat seagulls and ducklings. The gulls are held under water and drowned before being eaten headfirst. A flock of captive great white pelicans in St James' Park, London is well known for occasionally eating local pigeons, despite being well-fed.[23][24]

Breeding

The breeding season commences in April or May in temperate zones, is essentially all year around in Africa and runs February through April in India. Large numbers of these pelicans breed together in colonies.

Nest locations are variable. Some populations making stick nests in trees but a majority, including all those that breed in Africa, nest exclusively in scrapes on the ground lined with grass, sticks, feathers and other material.[20]

The female can lay from 1 to 4 eggs in a clutch, with two being the average.[3] The young are cared for by both parents. Incubation takes 29 to 36 days. The chicks are naked when they hatch but quickly sprout blackish-brown down. The colony gathers in "pods" around 20 to 25 days after the eggs hatch. The young fledge at 65 to 75 days of age. Around 64% of young successful reach adulthood, with sexual maturity attained at 3 to 4 years of age.[3]

Predators

White pelicans are often protected from bird-eating raptors by virtue of their own great size, but eagles, especially sympatric Haliaeetus species, may predate their eggs, nestlings, and fledglings. Occasionally, pelicans and their young are attacked at their colonies by mammalian carnivores from jackals to lions. As is common in pelicans, the close approach of a large predaceous or unknown mammal, including a human, at a colony will lead the pelican to abandon their nest in self-preservation.[25] Additionally, crocodiles, especially Nile crocodiles in Africa, readily kill and eat swimming pelicans.[26]

Status and conservation

Since 1998, the great white pelican has been rated as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. This is because it has a large range—more than 20,000 km2 (7700 mi2)—and because its population is thought not to have declined by 30% over ten years or three generations and thus is not a rapid enough decline to warrant a vulnerable rating. However, the state of the population overall is not known, and although it is widespread, it is not abundant anywhere.[1] It is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies. It is listed under the Appendix I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, Appendix II of the Berne Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats and Annexure I of the EU Birds Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds. It occurs within 43 Important Bird Areas in its European range, and is listed within 108 Special Protection Areas in the European Union.[1][27] This species is often kept in captivity, in zoos or in semi-wild colonies such as that in St. James's Park, London. The ancestors of this colony were originally given to Charles II by the Russian ambassador in 1664 which initiated the tradition of ambassadors donating the birds.[28]

Today, because of overfishing in certain areas, white pelicans are forced to fly long distances to find food. Great white pelicans are exploited for many reasons. Their pouch is used to make tobacco bags, Their skin is turned into leather, the guano is used as fertiliser, and the fat of young pelicans is converted into oils for traditional medicine in China and India. In Ethiopia, great white pelicans are shot for their meat. Human disturbance, loss of foraging habitat and breeding sites, and pollution are all contributing to the decline of the great white pelican. Declines have been particularly notable in the Palaearctic.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 BirdLife International (2012). "Pelecanus onocrotalus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Ali, Sálim (1997). Daniel, J.C., ed. The Book of Indian Birds (12th Rev ed.). Bombay, India: Bombay Natural History Society. ISBN 978-0-19-563731-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A.; Sargatal, J., eds. (1992). Handbook of the Birds of the World. 1. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-10-5.

- ↑ Fanshawe, John; Stevenson, Terry (2001). Birds of East Africa. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-85661-079-0.

- 1 2 3 Sinclair, Ian; Hockey, P. A. R.; Arlott, Norman (2005). The Larger Illustrated Guide to Birds of Southern Africa. Struik. p. 58. ISBN 9781770072435.

- 1 2 3 4 Jeyarajasingam, Allen (2012). A Field Guide to the Birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780199639434.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ↑ Harrison, Peter (1991). Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-60291-1.

- ↑ Dunning Jr., John B., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Porter, Richard; Aspinall, Simon (2016). Birds of the Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 9781472946003.

- ↑ Mclachlan, G.R.; Liversidge, R. (1978). "42 White Pelican". Roberts Birds of South Africa. Illustrated by Lighton, N.C.K.; Newman, K.; Adams, J.; Gronvöld, H. (4th ed.). The Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund. pp. 23–24.

- 1 2 3 Beaman, Mark; Madge, Steve (2010). The Handbook of Bird Identification: For Europe and the Western Palearctic. A&C Black. p. 84. ISBN 9781408135235.

- 1 2 Harrison, John (2011). A Field Guide to the Birds of Sri Lanka. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780199585663.

- ↑ Grimmett, Richard; Roberts, Tom J.; Inskipp, Tim; Byers, Clive (2008). Birds of Pakistan. A&C Black. p. 150. ISBN 9780713688009.

- 1 2 Brown, L. H.; Urban, Emil K. (1969-04-01). "The Breeding Biology of the Great White Pelican Pelecanus Onocrotalus Roseus at Lake Shala, Ethiopia". Ibis. 111 (2): 199–237. ISSN 1474-919X. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1969.tb02527.x.

- 1 2 3 4 Izhaki, Ido; Shmueli, Marva; Arad, Zeev; Steinberg, Yoav; Crivelli, Alain (2002-09-01). "Satellite Tracking of Migratory and Ranging Behavior of Immature Great White Pelicans". Waterbirds. 25 (3): 295–304. ISSN 1524-4695. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2002)025[0295:STOMAR]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Crivelli, Alain J.; Leshem, Yossi; Mitchev, Taniu; Jerrentrup, Hans (1991). "Where Do Palaearctic Great White Pelicans (Pelcanus Onocratalus) Presently Over Winter ?" (PDF). Revue d Ecologie. 46.

- ↑ Izhaki, Ido (1994-06-01). "Preliminary Data on the Importance of Israel for the Conservation of the White Pelican Pelecanus Onocrotalus L.". Ostrich. 65 (2): 213–217. ISSN 0030-6525. doi:10.1080/00306525.1994.9639684.

- ↑ Jeyarajasingam, Allen (2012). A Field Guide to the Birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780199639434.

- 1 2 Crawford, R.J.M. (2005). Hockey, P.A.R.; Dean, W.R.J.; Ryan, P.G., eds. Great White Pelican. Roberts – Birds of Southern Africa (7th ed.). Cape Town: The Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund. pp. 614–615.

- ↑ Attenborough, David (2009). "Birds". Life. Episode 5. BBC. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ Ryan, P. (2007). "Going, going, Gannet...Tough times for Benguela Seabirds" (PDF). African Birds & Birding: 30–35.

- ↑ "Pelican Swallows Pigeon in Park". BBC News. 25 October 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2006.

- ↑ Clarke, James (30 October 2006). "Pelican's Pigeon Meal not so Rare". BBC News. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ↑ McLean, Nancy. "The Great White Pelican (Peleconus onothotations)" (PDF). Northwestwildlife.

- ↑ Ross, Charles A.; Garnett, Stephen, eds. (1989). Crocodiles and Alligators. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0-8160-2174-1.

- ↑ Anonymous. "Proposal for Inclusion of Species on the Appendices of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals" (PDF). Government of the Federal Republic of Germany. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-02. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- ↑ "Pelicans". Royalparks. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pelecanus onocrotalus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Pelecanus onocrotalus |

- (Great) White Pelican Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- BirdLife species factsheet for Pelecanus onocrotalus

- "Pelecanus onocrotalus". Avibase.

- "Great white pelican media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Great white pelican photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Pelecanus onocrotalus at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Great white pelican on Xeno-canto.