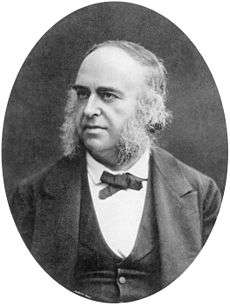

Paul Broca

| Pierre Paul Broca | |

|---|---|

|

Pierre Paul Broca | |

| Born |

28 June 1824 Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, Gironde |

| Died |

9 July 1880 (aged 56) Paris |

| Nationality | French |

| Fields | Anthropology, anatomy, medicine |

Pierre Paul Broca (/broʊˈkɑː/ or /ˈbroʊkə/; 28 June 1824 – 9 July 1880) was a French physician, anatomist and anthropologist. He was born in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, Gironde. He is best known for his research on Broca's area, a region of the frontal lobe that has been named after him. Broca's Area is involved with language. His work revealed that the brains of patients suffering from aphasia contained lesions in a particular part of the cortex, in the left frontal region. This was the first anatomical proof of the localization of brain function. Broca's work also contributed to the development of physical anthropology, advancing the science of anthropometry.[1]

Personal life

Paul Broca was born on 28 June 1824 in Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, Bordeaux, France, the son of Benjamin Broca, a medical practitioner and former surgeon in Napoleon's service. Broca's mother was a well-educated daughter of a Protestant preacher.[2] Broca received basic education in the school in his hometown, earning a bachelor's degree at the age of 16. He entered medical school in Paris when he was 17, and graduated at 20, when most of his contemporaries were just beginning as medical students.[3]

After graduating, Broca undertook an extensive internship, first with the urologist and dermatologist Philippe Ricord (1800–1889) at the Hôpital du Midi, then in 1844 with the psychiatrist François Leuret (1797–1851) at the Bicêtre. In 1845, he became an intern with Pierre Nicolas Gerdy (1797–1856), a great anatomist and surgeon. After two years with Gerdy, Broca became his assistant.[3]

In 1848, Broca founded a society of free-thinkers, sympathetic to Charles Darwin's theories. Broca was fascinated by the concept of evolution and once remarked, "I would rather be a transformed ape than a degenerate son of Adam".[3][4]

This brought him into conflict with the church, which regarded him as a subversive, materialist, and a corrupter of the youth. The church’s animosity toward him continued throughout his lifetime, resulting in numerous confrontations between Broca and the ecclesiastical authorities.[3]

In 1848, Broca became Prosector of anatomy at the University of Paris Medical School. He was also appointed secretary to the Société Anatomique. In 1849, he was awarded a medical doctorate. In 1859, in association with Étienne Eugène Azam, Charles-Pierre Denonvilliers, François Anthime Eugène Follin, and Alfred-Armand-Louis-Marie Velpeau, Broca performed the first experiments in Europe using hypnotism as surgical anesthesia.[3]

In 1853, Broca became professor agrégé, and was appointed surgeon of the hospital. He was elected to the chair of external pathology at the Faculty of Medicine in 1867, and one year later professor of clinical surgery. In 1868, he was elected a member of the Académie de medicine, and appointed the Chair of clinical surgery. He served in this capacity until his death. He worked for the Hôpital St. Antoine, the Pitié, the Hôtel des Clinques, and the Hôpital Necker.[3]

In parallel with his medical career, Broca pursued his interest in anthropology. In 1859, he founded the Society of Anthropology of Paris. He served as the secretary of the society from 1862. In 1872, he founded the journal Revue d'anthropologie, and in 1876, the Institute of Anthropology. The Church opposed the development of anthropology in France, and in 1876 organized a campaign to stop the teaching of the subject in the Anthropological Institute.[1][3]

Near the end of his life, Paul Broca was elected a lifetime member of the French Senate. He was also a member of the Académie française and held honorary degrees from many learned institutions, both in France and abroad.[3]

Broca died of a brain hemorrhage on 9 July 1880, at the age of 56.[1] His two sons both became distinguished professors of medical science.[3]

He was an atheist and identified as a Liberal.[5]

Research

Broca's early scientific works dealt with the histology of cartilage and bone, but he also studied cancer pathology, the treatment of aneurysms, and infant mortality. One of his major concerns was the comparative anatomy of the brain. As a neuroanatomist he made important contributions to the understanding of the limbic system and rhinencephalon. Olfaction was for him a sign of animality. He wrote extensively on biological evolution, then known as transformism in France (the term was also adopted in English at the time but is today used little in either language).[3]

In his later career, Broca wrote on public health and public education. He engaged in the discussion on the health care for the poor, becoming an important figure in the Assistance Publique. He also advocated secular education for women and famously opposed Félix-Antoine-Philibert Dupanloup (1802–1878), Roman Catholic bishop of Orléans, who wanted to keep control of women's education.[3]

One of Broca's major areas of expertise was the comparative anatomy of the brain. His research on the localization of speech led to entirely new research into the lateralization of brain function.[3]

Speech research

Broca is celebrated for his discovery of the speech production center of the brain located in the ventroposterior region of the frontal lobes (now known as Broca's area). He arrived at this discovery by studying the brains of aphasic patients (persons with speech and language disorders resulting from brain injuries).[6]

This area of study began for Broca with the dispute between the proponents of cerebral localization – whose views derived from the phrenology of Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) – and their opponents led by Pierre Flourens (1794–1867) – who claimed that, by careful ablation (specific way of removing material) of various brain regions, he had disproved Gall's hypotheses. However, Gall's former student, Jean-Baptiste Bouillaud (1796–1881), kept the localization of function hypothesis alive (especially with regards to a "language center"), although he rejected much of the rest of phrenological thinking. Bouillaud challenged professionals of the time to disprove him by finding a case of frontal lobe damage unaccompanied by a disorder of speech. His son-in-law, Ernest Aubertin (1825–1893), began seeking out cases to either support or disprove the theory, and he found several in support of it.[6]

Broca's Society of Anthropology of Paris became the new platform for the localization of function controversy when several experts of head and brain anatomy joined, including Aubertin. Most of these experts still supported Flourens argument, but Aubertin was persistent in presenting new patients to counter their views. However, it was Broca, not Aubertin, who finally put the localization of function existence issue to rest.[6]

In 1861, Broca heard of a patient, named Louis Victor Leborgne,[7] in the Bicêtre Hospital who had a 21-year progressive loss of speech and paralysis but not a loss of comprehension nor mental function. He was nicknamed "Tan" due to his inability to clearly speak any words other than "tan".[6][8]

When Leborgne died just a few days later, Broca performed an autopsy. He determined that, as predicted, Leborgne did in fact have a lesion in the frontal lobe of the left cerebral hemisphere. From a comparative progression of Leborgne's loss of speech and motor movement, the area of the brain important for speech production was determined to lie within the third convolution of the left frontal lobe, next to the lateral sulcus. For the next two years, Broca went on to find autopsy evidence from 12 more cases in support of the localization of articulated language.[6][8]

Although history credits this discovery to Broca, another French neurologist, Marc Dax, made similar observations a generation earlier, but he died shortly after with no chance to further his evidence. Today the brains of many of Broca's aphasic patients are still preserved in the Musée Dupuytren, and his collection of casts in the Musée d'Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière. Broca presented his study on Leborgne in 1861 in the Bulletin of the Société Anatomique.[6][8]

Patients with damage to Broca's area and/or to neighboring regions of the left inferior frontal lobe are often categorized clinically as having Expressive aphasia (also known as Broca's aphasia). This type of aphasia, which often involves impairments in speech output, can be contrasted with Receptive aphasia, (also known as Wernicke's aphasia), named for Karl Wernicke, which is characterized by damage to more posterior regions of the left temporal lobe, and is often characterized by impairments in language comprehension.[6][8]

Anthropological research

Broca first became acquainted with anthropology through the works of Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1805–1861), Antoine Étienne Reynaud Augustin Serres (1786–1868) and Jean Louis Armand de Quatrefages de Bréau (1810–1892), and anthropology soon became his lifetime interest. He spent much time at his Anthropological Institute, studying skulls and bones. In that sense, Broca was a pioneer in the study of physical anthropology. He advanced the science of cranial anthropometry by developing many new types of measuring instruments (craniometers) and numerical indices.[3]

Broca also contributed to the field of comparative anatomy of primates and humans. He was interested in the relationship between anatomical features of the brain and mental capabilities, such as intelligence. He believed, as did many in his time, that man's intellectual qualities could be measured by the size of his brain. From his research, he asserted that men had larger brains than woman and that "superior races" had larger brains than "inferior races". Modern scientists such as Stephen Jay Gould have criticised Broca's research for using a priori expectations and scientific racism.[9]

Broca published around 223 papers on general anthropology, physical anthropology, ethnology, and other branches of this field. He founded the Société d'Anthropologie de Paris in 1859, the Revue d'Anthropologie in 1872, and the School of Anthropology in Paris in 1876.

Broca's legacy

The discovery of Broca's area revolutionized the understanding of language processing, speech production, and comprehension, as well as what effects damage to this area may cause. Broca played a major role in the localization of function debate, by resolving the issue scientifically with Leborgne and his 12 cases thereafter. His research led others to discover the location of a wide variety of other functions, specifically Wernicke's area.

New research has found that dysfunction in the area may lead to other speech disorders such as stuttering and apraxia of speech. Recent anatomical neuroimaging studies have shown that the pars opercularis of Broca's area is anatomically smaller in individuals who stutter whereas the pars triangularis appears to be normal.

He also invented more than 20 measuring instruments for the use in craniology, and helped standardize measuring procedures.[3]

His name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

Publications

- Broca, Paul. 1849. De la propagation de l'inflammation – Quelques propositions sur les tumeurs dites cancéreuses. Doctoral dissertation.

- Broca, Paul. 1856. Traité des anévrismes et leur traitement. Paris: Labé & Asselin

- Broca, Paul. 1861. Sur le principe des localisations cérébrales. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 2: 190–204.

- Broca, Paul. 1861. Perte de la parole, ramollissement chronique et destruction partielle du lobe antérieur gauche. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 2: 235–38.

- Broca, Paul. 1861. Nouvelle observation d'aphémie produite par une lésion de la moitié postérieure des deuxième et troisième circonvolution frontales gauches. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique 36: 398–407.

- Broca, Paul. 1863. Localisations des fonctions cérébrales. Siège de la faculté du language articulé. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie 4: 200–208.

- Broca, Paul. 1864. On the phenomena of hybridity in the genus Homo. London: Pub. for the Anthropological society, by Longman, Green, Longman, & Roberts

- Broca, Paul. 1866. Sur la faculté générale du language, dans ses rapports avec la faculté du language articulé. Bulletin de la Société d"Anthropologie deuxième série 1: 377–82

- Broca, Paul. 1871–1878. Mémoires d'anthropologie, 3 vols. Paris: C. Reinwald

References

- 1 2 3 "Dr. Paul Broca". Science. 1 (8): 93. 21 August 1880. JSTOR 2900242. doi:10.1126/science.os-1.9.93.

- ↑ Schiller, 1979, p. 12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Memoir of Paul Broca". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 10: 242–261. 1881. JSTOR 2841526.

- ↑ Sagan, Carl. 1979. Broca's Brain. Random House: New York ISBN 1439505241.

- ↑ "Paul Broca (1824-80)". sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

He was a left-wing atheist who argued against African enslavement.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fancher, Raymond E. Pioneers of Psychology , 2nd ed. (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1990 (1979), pp. 72–93.

- ↑ "Identity of Famous 19th-Century Brain Discovered". Live Science. Archived from the original on 2016-06-14. Retrieved 2017-01-24.

- 1 2 3 4 Broca, Paul. “Remarks on the Seat of the Faculty of Articulated Language, Following an Observation of Aphemia (Loss of Speech)”. Bulletin de la Société Anatomique, Vol. 6, (1861), 330–357.

- ↑ Gould, Steven Jay (1981). The Mismeasure of Man (1st ed.). New York: Norton. pp. 83–84. ISBN 0-393-01489-4.

Literature

- Androutsos G, Diamantis A (2007). "Paul Broca (1824–1880): founder of anthropology, pioneer of neurology and oncology". Journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology. 12 (4): 557–64. PMID 18067221.

- Alajouanine T, Signoret JL (1980). "Paul Broca and aphasia" [Paul Broca and aphasia]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (6): 545–51. PMID 7008915.

- Bendiner E (November 1986). "Paul Broca: adventurer in the recesses of the mind". Hospital Practice. 21 (11A): 104–12, 117, 120–1 passim. PMID 3097033.

- Buckingham HW (2006). "The Marc Dax (1770–1837)/Paul Broca (1824–1880) controversy over priority in science: left hemisphere specificity for seat of articulate language and for lesions that cause aphemia". Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 20 (7–8): 613–9. PMID 17056493. doi:10.1080/02699200500266703.

- Cambier J (July 1980). "Paul Broca, 100 years after his death, 1880–1980" [Paul Broca, 100 years after his death, 1880–1980]. La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French). 9 (29): 1983. PMID 6995932.

- Castaigne P (1980). "Paul Broca (1824–1880)" [Paul Broca (1824–1880)]. Revue neurologique (in French). 136 (10): 559–62. PMID 7010498.

- Clower WT, Finger S (December 2001). "Discovering trepanation: the contribution of Paul Broca". Neurosurgery. 49 (6): 1417–25; discussion 1425–6. PMID 11846942. doi:10.1097/00006123-200112000-00021.

- "Commemoration of the centenary of the death of Paul Broca" [Commemoration of the centenary of the death of Paul Broca]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 773–93. 1980. PMID 7011701.

- Cowie SE (2000). "A place in history: Paul Broca and cerebral localization". Journal of Investigative Surgery. 13 (6): 297–8. PMID 11202005. doi:10.1080/089419300750059334.

- D'Aubigné RM (1980). "Paul Broca and surgery of the motor system" [Paul Broca and surgery of the motor system]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 791–3. PMID 7011706.

- Dechaume M, Huard P (1980). "Paul Broca (182401880). Dentist or dentistry in the last century" [Paul Broca (182401880). Dentist or dentistry in the last century]. Actualités Odonto-stomatologiques (in French). 34 (132): 537–43. PMID 7015804.

- Delmas A (1980). "Paul Broca and anatomy" [Paul Broca and anatomy]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (6): 552–6. PMID 7008916.

- Denoix P (1980). "Paul Broca : pathological anatomy, cancer, statistics (author's transl)" [Paul Broca : pathological anatomy, cancer, statistics]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 787–90. PMID 7011705.

- Finger S (June 2004). "Paul Broca (1824–1880)". Journal of Neurology. 251 (6): 769–70. PMID 15311362. doi:10.1007/s00415-004-0456-6.

- Frédy D (1996). "Paul Broca (1824–1880)" [Paul Broca (1824–1880)]. Histoire des sciences médicales (in French). 30 (2): 199–208. PMID 11624874.

- Greenblatt SH (1970). "Huglings Jackson's first encounter with the work of Paul Broca: the physiological and philosophical background". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 44 (6): 555–70. PMID 4925020.

- Harris LJ (January 1991). "Cerebral control for speech in right-handers and left-handers: an analysis of the views of Paul Broca, his contemporaries, and his successors". Brain and Language. 40 (1): 1–50. PMID 2009444. doi:10.1016/0093-934X(91)90115-H.

- Huard P, Aaron C, Askienazy S, Corlieu P, Fredy D, Vedrenne C (October 1980). "The death of Paul Broca (1824–1880)" [The death of Paul Broca (1824–1880)]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (7): 682–5. PMID 7013939.

- Huard P (1980). "Paul Broca, anatomist (author's transl)" [Paul Broca, anatomist]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 774–6. PMID 7011702.

- Huard P, Aaron C, Askienazy S, Corlieu P, Fredy D, Vedrenne C (March 1982). "The brain of Paul Broca (1824–1880). Correlation of pathological and computed tomography findings (author's transl)" [The brain of Paul Broca (1824–1880). Correlation of pathological and computed tomography findings]. Journal de Radiologie (in French). 63 (3): 175–80. PMID 7050373.

- Huard P (October 1961). "Paul BROCA (1824–1880)" [Paul BROCA (1824–1880)]. Concours Médical (in French). 83: 4917–20. PMID 14036412.

- Huard P (October 1961). "Paul BROCA (1829–1880)" [Paul BROCA (1829–1880)]. Concours Médical (in French). 83: 5069–74 concl. PMID 14036413.

- Houdart R (1980). "Paul Broca : precursor of neurological disciplines (author's transl)" [Paul Broca : precursor of neurological disciplines]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 783–6. PMID 7011704.

- Jay V (March 2002). "Pierre Paul Broca". Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. 126 (3): 250–1. ISSN 0003-9985. PMID 11860295. doi:10.1043/0003-9985(2002)126<0250:PPB>2.0.CO;2.

- LaPointe, Leonard (2012). Paul Broca and the Origins of Language in the Brain. San Diego, Plural Publishing, Inc.

- Lee DA (May 1981). "Paul Broca and the history of aphasia: Roland P. Mackay Award Essay, 1980". Neurology. 31 (5): 600–2. PMID 7015163. doi:10.1212/wnl.31.5.600.

- Leischner A (May 1972). "Paul Broca and significance of his works for clinical pathology of the brain" [Paul Broca and significance of his works for clinical pathology of the brain]. Bratislavské Lekárske Listy (in Slovak). 57 (5): 615–23. PMID 4554955.

- Lukács D (August 1980). "Pierre Paul Broca, founder of anthropology and discoverer of the cortical speech center" [Pierre Paul Broca, founder of anthropology and discoverer of the cortical speech center]. Orvosi Hetilap (in Hungarian). 121 (34): 2081–2. PMID 7005822.

- Monod-Broca P (October 2001). "Paul Broca: 1824–1880". Annales de Chirurgie (in French). 126 (8): 801–7. PMID 11692769. doi:10.1016/S0003-3944(01)00600-9.

- Monod-Broca P (1980). "Paul Broca (1824–1880). The surgeon, the man" [Paul Broca (1824–1880). The surgeon, the man]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (6): 536–44. PMID 7008914.

- Monod-Broca P (April 2006). "The other Paul Broca" [The other Paul Broca]. La Revue du praticien (in French). 56 (8): 923–5. PMID 16764255.

- Natali J (1980). "Paul Broca, vascular surgeon (author's transl)" [Paul Broca, vascular surgeon]. Chirurgie (in French). 106 (10): 777–82. PMID 7011703.

- Olry R, Nicolay X (1994). "From Paul Broca to the long-term potentiation: the difficulties in confirming a limbic identity" [From Paul Broca to the long-term potentiation: the difficulties in confirming a limbic identity]. Histoire Des Sciences Médicales (in French). 28 (3): 199–203. PMID 11640329.

- Pineau H (1980). "Paul Broca and anthropology" [Paul Broca and anthropology]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (6): 557–62. PMID 7008917.

- Schiller F (May 1983). "Paul Broca and the history of aphasia". Neurology. 33 (5): 667. PMID 6341875. doi:10.1212/wnl.33.5.667.

- Schiller, Francis (1979). Paul Broca, Founder of French Anthropology, Explorer of the Brain. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03744-8.

- Stone JL (July 1991). "Paul Broca and the first craniotomy based on cerebral localization". Journal of Neurosurgery. 75 (1): 154–9. PMID 2045905. doi:10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0154.

- Valette G (1980). "Address at the meeting dedicated to the centenary of the death of Paul Broca (1824–1880)" [Address at the meeting dedicated to the centenary of the death of Paul Broca (1824–1880)]. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine (in French). 164 (6): 535. PMID 7008913.

- Wyplosz J (May 2003). "Paul Broca: the protohistory of neurosurgery" [Paul Broca: the protohistory of neurosurgery]. La Revue du praticien (in French). 53 (9): 937–40. PMID 12816030.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Broca, Paul. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by or about Paul Broca at Internet Archive

- "Paul Broca's discovery of the area of the brain governing articulated language", analysis of Broca's 1861 article, on BibNum [click 'à télécharger' for English version].