Division of Korea

Part of a series on the |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Korea | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Prehistory | ||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Proto–Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| North–South States | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Later Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Unitary dynastic period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Division of Korea | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

The division of Korea between North and South Korea was the result of the Allied victory in World War II in 1945, ending the Empire of Japan's 35-year rule of Korea. The United States and the Soviet Union occupied the country, with the boundary between their zones of control along the 38th parallel.

With the onset of the Cold War, negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union failed to lead to an independent, unified Korea. In 1948, UN-supervised elections were held in the US-occupied south only. This led to the establishment of the Republic of Korea in South Korea, which was promptly followed by the establishment of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea in North Korea. The United States supported the South, and the Soviet Union supported the North, and each government claimed sovereignty over the whole Korean peninsula.

The Korean War (1950–1953) left the two Koreas separated by the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) for the rest of the Cold War and beyond.

Historical background

Korea under Japanese rule (1910–1945)

When the Russo-Japanese War ended in 1905 Korea became a nominal protectorate of, and was annexed in 1910 by, Japan. The Korean king Gojong was removed. In the following decades, nationalist and radical groups emerged, mostly in exile, to struggle for independence. Divergent in their outlooks and approaches, these groups failed to unite in one national movement.[1][2] The Korean Provisional Government in China failed to obtain widespread recognition.[3]

End of World War II

In November 1943, Franklin Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Chiang Kai-shek met at the Cairo Conference to discuss what should happen to Japan's colonies, and agreed that Japan should lose all the territories it had conquered by force. In the declaration after this conference, Korea was mentioned for the first time. The three powers declared that they were, "mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, ... determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent."[4][5]

.gif)

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943 and the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Soviet Union promised to join its allies in the Pacific War in two to three months after victory in Europe. On August 8, 1945, three months to the day after the end of hostilities in Europe, and two days after the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan.[6] Soviet troops advanced rapidly, and the US government became anxious that they would occupy the whole of Korea. On August 10, 1945 two young officers – Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel – were assigned to define an American occupation zone. Working on extremely short notice and completely unprepared, they used a National Geographic map to decide on the 38th parallel. They chose it because it divided the country approximately in half but would place the capital Seoul under American control. No experts on Korea were consulted. The two men were unaware that forty years before, Japan and pre-revolutionary Russia had discussed sharing Korea along the same parallel. Rusk later said that had he known, he "almost surely" would have chosen a different line.[7][8] The division placed sixteen million Koreans in the American zone and nine million in the Soviet zone.[9] To the surprise of the Americans, the Soviet Union immediately accepted the division. The agreement was incorporated into General Order No. 1 (approved on 17 August 1945) for the surrender of Japan.[10]

Soviet forces began amphibious landings in Korea by August 14 and rapidly took over the north-east of the country, and on August 16 they landed at Wonsan.[11] On August 24, the Red Army reached Pyongyang.[10]

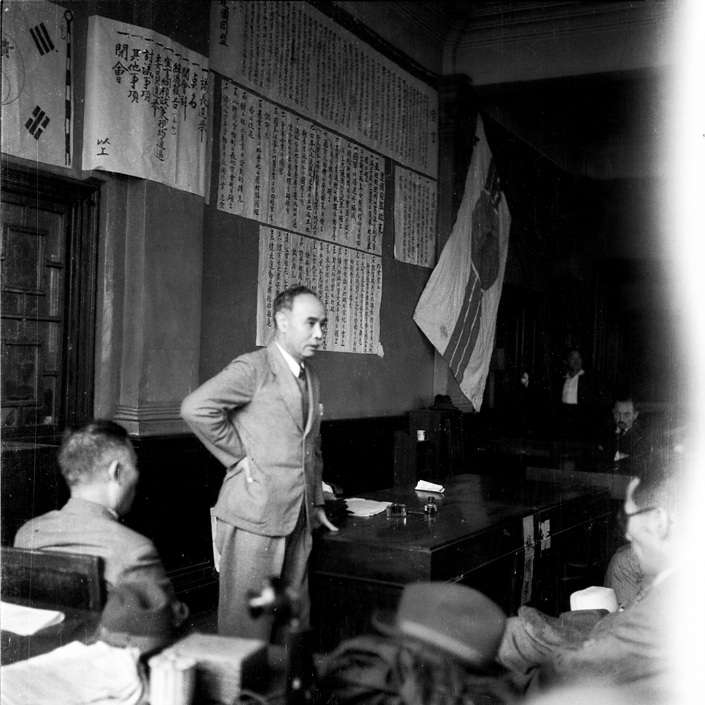

General Abe Nobuyuki, the last Japanese Governor-General of Korea, had established contact with a number of influential Koreans since the beginning of August 1945 to prepare the hand-over of power. Throughout August, Koreans organized people's committee branches for the "Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence" (CPKI, 조선건국준비위원회), headed by Lyuh Woon-hyung, a left-wing politician. On September 6, 1945, a congress of representatives was convened in Seoul and founded the short-lived People's Republic of Korea.[12][13]

Post-World War II

In December 1945, at the Moscow Conference, the Allies agreed that the Soviet Union, the US, the Republic of China, and Britain would take part in a trusteeship over Korea for up to five years in the lead-up to independence. Many Koreans demanded independence immediately; however, the Korean Communist Party, which was closely aligned with the Soviet Communist party, supported the trusteeship.[14][15] The US President Franklin Roosevelt had initiated the idea of the trusteeship for Korea in 1943.[16]

A Soviet-US Joint Commission met in 1946 and 1947 to work towards a unified administration, but failed to make progress due to increasing Cold War antagonism and to Korean opposition to the trusteeship.[17] Meanwhile, the division between the two zones deepened. The difference in policy between the occupying powers led to a polarization of politics, and a transfer of population between North and South.[18] In May 1946 it was made illegal to cross the 38th parallel without a permit.[19]

US occupation of South Korea

With the American government fearing Soviet expansion, and the Japanese authorities in Korea warning of a power vacuum, the embarkation date of the US occupation force was brought forward three times.[3]

On September 7, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur announced that Lieutenant General John R. Hodge was to administer Korean affairs, and Hodge landed in Incheon with his troops the next day. The Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, which had operated from China, sent a delegation with three interpreters to Hodge, but he refused to meet with them.[20] Likewise, Hodge refused to recognize the newly formed People's Republic of Korea and its People's Committees, and outlawed it on 12 December.[21]

In September 1946, thousands of laborers and peasants rose up against the military government. This uprising was quickly defeated, and failed to prevent scheduled October elections for the South Korean Interim Legislative Assembly.

The ardent anti-communist Syngman Rhee, who had been the first president of the Provisional Government and later worked as a pro-Korean lobbyist in the US, became the most prominent politician in the South. On July 19, 1947, Lyuh Woon-hyung, the last senior politician committed to left-right dialogue, was assassinated by a right-winger.[22]

The government conducted a number of military campaigns against left-wing insurgents. Over the course of the next few years, between 30,000[23] and 100,000 people were killed.[24]

Soviet occupation of North Korea

When Soviet troops entered Pyongyang, they found a local branch of the Committee for the Preparation of Korean Independence operating under the leadership of veteran nationalist Cho Man-sik.[25] The Soviet Army allowed these "People's Committees" (which were friendly to the Soviet Union) to function. Colonel-General Terentii Shtykov set up the Soviet Civil Administration, taking control of the committees and placing communists in key positions.

In February 1946 a provisional government called the Provisional People's Committee was formed under Kim Il-sung, who had spent the last years of the war training with Soviet troops in Manchuria. Conflicts and power struggles ensued at the top levels of government in Pyongyang as different aspirants maneuvered to gain positions of power in the new government. In March 1946 the provisional government instituted a sweeping land-reform program: land belonging to Japanese and collaborator landowners was divided and redistributed to poor farmers.[26] Organizing the many poor civilians and agricultural laborers under the people's committees, a nationwide mass campaign broke the control of the old landed classes. Landlords were allowed to keep only the same amount of land as poor civilians who had once rented their land, thereby making for a far more equal distribution of land. The North Korean land reform was achieved in a less violent way than in China or in Vietnam. Official American sources stated: "From all accounts, the former village leaders were eliminated as a political force without resort to bloodshed, but extreme care was taken to preclude their return to power."[27] The farmers responded positively; many collaborators and former landowners fled to the south, where some of them obtained positions in the new South Korean government. According to the U.S. military government, 400,000 northern Koreans went south as refugees.[28]

Key industries were nationalized. The economic situation was nearly as difficult in the north as it was in the south, as the Japanese had concentrated agriculture in the south and heavy industry in the north.

Soviet forces departed in 1948.[29]

UN intervention and the formation of separate governments

With the failure of the Joint Commission to make progress, the US brought the problem before the United Nations in September 1947. The Soviet Union opposed UN involvement. At that time, the US had more influence over the UN than the USSR.[30] The UN passed a resolution on November 14, 1947, declaring that free elections should be held, foreign troops should be withdrawn, and a UN commission for Korea, the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK), should be created. The Soviet Union boycotted the voting and did not consider the resolution to be binding, arguing that the UN could not guarantee fair elections. In the absence of Soviet co-operation, it was decided to hold UN-supervised elections in the south only.[31][32] Some UNTCOK delegates felt that the conditions in the south gave unfair advantage to right-wing candidates, but they were overruled.[33]

The decision to proceed with separate elections was unpopular among many Koreans, who rightly saw it as a prelude to a permanent division of the country. General strikes in protest against the decision began in February 1948.[19] In April, Jeju islanders rose up against the looming division of the country. South Korean troops were sent to repress the rebellion. Tens of thousands of islanders were killed and by one estimate, 70% of the villages were burned by the South Korean troops.[34] The uprising flared up again with the outbreak of the Korean War.[35]

In April 1948, a conference of organizations from the north and the south met in Pyongyang, but the conference produced no results. The southern politicians Kim Koo and Kim Kyu-sik attended the conference and boycotted the elections in the south, as did other politicians and parties.[36][37] Kim Koo was assassinated the following year.[38]

On May 10, 1948 the south held a general election. On August 15, the "Republic of Korea" formally took over power from the U.S. military, with Syngman Rhee as the first president. In the North, the "Democratic People's Republic of Korea" was declared on September 9, with Kim Il-sung as prime minister.

On December 12, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly accepted the report of UNTCOK and declared the Republic of Korea to be the "only lawful government in Korea".[39]

Unrest continued in the South. In October 1948, the Yeosu–Suncheon Rebellion took place, in which some regiments rejected the suppression of the Jeju uprising and rebelled against the government.[40] In 1949, the Syngman Rhee government established the Bodo League in order to keep an eye on its political opponents. The majority of the Bodo League's members were innocent farmers and civilians who were forced into membership.[41] The registered members or their families were executed at the beginning of the Korean War. On December 24, 1949, South Korean Army massacred Mungyeong citizens who were suspected communist sympathizers or their family and affixed blame to communists.[42]

Korean War

This division of Korea, after more than a millennium of being unified, was seen as controversial and temporary by both regimes. From 1948 until the start of the civil war on June 25, 1950, the armed forces of each side engaged in a series of bloody conflicts along the border. In 1950, these conflicts escalated dramatically when North Korean forces invaded South Korea, triggering the Korean War. The North overran much of the South until pushed back by a US-led United Nations intervention. The UN forces then occupied most of the North, until Chinese forces intervened and restored communist control of the North.

The Korean Armistice Agreement was signed after three years of war. The two sides agreed to create a four-kilometer-wide buffer zone between the states, known as the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). This new border, reflecting the territory held by each side at the end of the war, crossed the 38th parallel diagonally.

Geneva Conference and NNSC

As dictated by the terms of the Korean Armistice, a Geneva Conference was held in 1954 on the Korean question. Despite efforts by many of the nations involved, the conference ended without a declaration for a unified Korea.

The Armistice established a Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC) which was tasked to monitor the Armistice. Since 1953, members of the Swiss[43] and Swedish[44] Armed Forces have been members of the NNSC stationed near the DMZ.

Post-armistice relations

Since the war, Korea has remained divided along the DMZ. North and South have remained in a state of conflict, with the opposing regimes both claiming to be the legitimate government of the whole country. Sporadic negotiations have failed to produce lasting progress towards reunification.[45]

See also

- List of border incidents involving North Korea

- Korean conflict

- Korean reunification

- North Korea–South Korea relations

- History of North Korea

- History of South Korea

- Partition of Vietnam

Notes

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 31–37. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 156–160. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- 1 2 Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 159–160. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ "Cairo Communique, December 1, 1943". Japan National Diet Library. December 1, 1943.

- ↑ Savada, Andrea Matles; Shaw, William, eds. (1990), "World War II and Korea", South Korea: A Country Study, GPO, Washington, DC: Library of Congress

- ↑ Walker, J Samuel (1997). Prompt and Utter Destruction: Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 82. ISBN 0-8078-2361-9.

- ↑ Oberdorfer, Don; Carlin, Robert (2014). The Two Koreas: A Contemporary History. Basic Books. p. 5. ISBN 9780465031238.

- ↑ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 306. ISBN 9780742567177. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- 1 2 Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 18.

- ↑ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A Concise History of Modern Korea: From the Late Nineteenth Century to the Present. Hawaìi studies on Korea. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 86. ISBN 9780742567139. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 53–57. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Bluth, Christoph (2008). Korea. Cambridge: Polity Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-07456-3357-2.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 187–188. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 59–60, 65. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- 1 2 Hyung Gu Lynn (2007). Bipolar Orders: The Two Koreas since 1989. Zed Books. p. 20.

- ↑ Hart-Landsberg, Martin (1998). Korea: Division, Reunification, & U.S. Foreign Policy. Monthly Review Press. pp. 71–77.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 65. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Arthur Millet, The War for Korea, 1945–1950 (2005).

- ↑ Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings, Korea: The Unknown War, Viking Press, 1988, ISBN 0-670-81903-4.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce. The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945–1947. Princeton University Press, 1981, 607 pages, ISBN 0-691-09383-0.

- ↑ Allan R. Millet, The War for Korea: 1945–1950 (2005) p. 59.

- ↑ Gbosoe, Gbingba T. (2006). Modernization of Japan. iUniverse. p. 212. ISBN 9780595411900. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

Although Soviet occupation forces were withdrawn on December 10, 1948, [...] the Soviets had maintained ties with the Democratic Peoples' Republic of Korea [...]

- ↑ Lone, Stewart; McCormack, Gavan (1993). Korea since 1850. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-84668-067-0.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 211–212. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ "Ghosts of Cheju". Newsweek. 2000-06-19. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ Robinson, Michael E (2007). Korea's Twentieth-Century Odyssey. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8248-3174-5.

- ↑ Cumings, Bruce (2005). Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 211, 507. ISBN 0-393-32702-7.

- ↑ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-84668-067-0.

- ↑ Jager, Sheila Miyoshi (2013). Brothers at War – The Unending Conflict in Korea. London: Profile Books. pp. 48, 496. ISBN 978-1-84668-067-0.

- ↑ Buzo, Adrian (2002). The Making of Modern Korea. London: Routledge. p. 67. ISBN 0-415-23749-1.

- ↑ "439 civilians confirmed dead in Yeosu-Suncheon Uprising of 1948 New report by the Truth Commission places blame on Syngman Rhee and the Defense Ministry, advises government apology". The Hankyoreh. 8 January 2009. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ↑ "Gov’t Killed 3,400 Civilians During War". The Korea Times. 2 March 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ↑ 두 민간인 학살 사건, 상반된 판결 왜 나왔나?'울산보도연맹' – '문경학살사건' 판결문 비교분석해 봤더니.... OhmyNews (in Korean). 2009-02-17. Archived from the original on 2011-05-03. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- ↑ "NNSC in Korea" (PDF). Swiss Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Korea". Swedish Armed Forces. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010.

- ↑ Feffer, John (June 9, 2005). "Korea's slow-motion reunification". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

References

- Oberdorfer, Don. The Two Koreas : A Contemporary History. Addison-Wesley, 1997, 472 pages, ISBN 0-201-40927-5

- Cumings, Bruce. The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regimes, 1945-1947. Princeton University Press, 1981, 607 pages, ISBN 0-691-09383-0

- Hoare, James; Daniels, Gordon (February 2004). "The Korean Armistice North and South: The Low-Key Victory [Hoare]; The British Press and the Korean Armistice: Antecedents, Opinions and Prognostications [Daniels]". The Korean Armistice of 1953 and its Consequences: Part I (PDF) (Discussion Paper No. IS/04/467 ed.). London: The Suntory Centre (London School of Economics).

External links

- South Korean Ministry of Unification (Korean and English)

- North Korean News Agency (Korean and English)

- Korea Web Weekly (English)

- NDFSK (Mostly Korean; some English)

- Koreascope (Korean and English)

- Rulers.org, has list of Post-World War II US and Soviet administrators (English)

- Korean Unification Studies