Italian Parliament

| Italian Parliament Parlamento Italiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses |

Senate of the Republic Chamber of Deputies |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

President of the Chamber of Deputies | |

| Structure | |

| Seats |

950 320 senators (315 elected + 5 for life) 630 deputies |

| |

Senate of the Republic political groups |

List

|

| |

Chamber of Deputies political groups |

List

|

| Elections | |

Senate of the Republic last election | 24–25 February 2013 |

Chamber of Deputies last election | 24–25 February 2013 |

| Meeting place | |

|

Chamber of Deputies: Palazzo Montecitorio Senate of the Republic: Palazzo Madama | |

| Website | |

| http://www.parlamento.it | |

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Italy |

| Constitution |

|

Legislature |

|

|

| Foreign relations |

|

Related topics |

The Italian Parliament (Italian: Parlamento Italiano) is the national parliament of the Italian Republic. The Parliament is the representative body of Italian citizens and is the successor to the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia (1848-1861) and the Parliament of the Kingdom of Italy (1861-1946). It is a bicameral legislature with 945 elected members and a small number of unelected members (parlamentari). It is composed of the Chamber of Deputies, with 630 members (deputati) elected on a national basis,[1] and the Senate of the Republic, with 315 members (senatori) elected on a regional basis, plus a small number (currently 5) of senators for life (senatori a vita), either appointed or ex officio.[2] The two houses are independent from one another and never meet jointly except under circumstances specified by the Constitution.

By the Republican Constitution of 1948, the two houses of the Italian Parliament possess the same powers: this particular form of parliamentary democracy (so-called perfect bicameralism) has been coded in the current form since the adoption of the Albertine Statute and resurged after the dismissal of the fascist dictatorship of the 1920s and 1930s during World War II.

Because the President of the Senate is acting Head of State in the absence of the President of the Republic, the President of the Senate and the Vice-Presidents of the Senate have a higher position than their respective counterparts of the Chamber of Deputies in the Italian order of precedence.[3] On the other hand, no distinction is made between deputies and senators.

Composition of the Parliament

The Chamber of Deputies has 630 elected members, while the Senate has 315 elected members. The number of deputies and senators was fixed by a constitutional amendment in 1963: in its original text, the Constitution provided for a variable number of Members of Parliament depending on the population.[4] The Senate of the Republic also includes a small number of unelected members (senators for life). There are two categories of senators for life. Former Presidents of the Republic are senators for life by law, unless they renounce this privilege. Furthermore, the President of the Republic can appoint up to five Italian citizens as senators for life "for outstanding merits in the social, scientific, artistic or literary field".[5]

Different voting ages are mandated for each house: any Italian citizen who is 18 or older can vote in the election of the Chamber of Deputies,[6] while the voting age for the Senate of the Republic is 25.[7] Similarly, the two houses have a different age of candidacy: deputies are required to be 25 or older,[6] while elected senators must be 40 or older.[7] No explicit age limit is required to be appointed senator for life (but Presidents of the Republic must be 50 or older).[8]

Functions of the Parliament

The main prerogative of the Parliament is the exercise of legislative power, that is the power to enact laws. For a bill to become law, it must receive the support of both houses independently in the same text. A bill is first introduced in one of the houses, amended, and then approved or rejected: if approved, it is passed to the other house, which can amend it before approving or rejecting it. If approved without amendments, the bill is then promulgated by the President of the Republic and becomes law. If approved with amendments, it is goes back to the other house. The process continues until the bill is approved in the same text by both houses (in which case it becomes law after promulgation) or is rejected by one house.

The Council of Ministers, which is led by the Prime Minister and is the national executive of Italy, needs to have the confidence of both houses.[9] It must receive a vote of confidence by both houses before being officially in power, and the Parliament can cast a motion of no confidence at any moment, which forces the Prime Minister and their Cabinet to resign. If the President of the Republic is unable to find a new Prime Minister able to receive the support of both houses, he or she can dissolve one or both houses and new elections are held.

Legislating

The process by which the Italian Parliament makes law, the iter legis, is as follows:

Proposals can be made by the Government, individual Members of Parliament (who must present their proposal to the Chamber that they are a member of), private citizens (who must present a proposal in the form of a draft law, approved by 50,000 voters), individual Regional Councils, and the National Council for Economics and Labour (CNEL).

Once a proposal is introduced in one of the two Chambers, it is assigned to a parliamentary committee to carry out preliminary inspection of the proposal (taking advantage of advice of other committees, especially, the so-called "filter committees"). At this point, two different procedures can be taken.

In the "normal procedure", the committee holds a referral meeting, drafts a response and names a spokesperson to report this response, then leaves the responsibility for composing and approving the bill's text to the assembly. This must be completed in no more than four months for the Chamber of Deputies and two months for the Senate. Once the bill has come before one of the chambers, a general discussion takes place, followed by the review (with a vote) article by article, and finally a vote on the whole bill, which is normally an open ballot (secret ballots are possible for matters of individual conscience). If the bill passes the vote in one chamber then it passes to the other chamber of the parliament, where it must be voted through without any further changes. If the other chamber does make any modifications to the bill then the new version of the bill must be returned to the first chamber to approve these changes. If the bill repeats this process many times it is said to be "shuttling" or "dribbling." This procedure is obligatory for bills which concern constitutional and electoral matters, the delegation of legislative power, the authorisation of the ratification of international treaties, the approval of the budget.[10]

In all other cases, the "special procedure" (also called the "decentralised legislative procedure") can be employed. In this case, the committee holds a drafting meeting (leaving only the final approval of the bill to the parliament), or a deliberative/legislative meeting (in which case the entire legislative process is carried out by the committee and the bill is not voted on by parliament at all). This procedure can be vetoed by the vote of one tenth of the members of the Chamber in which the bill was originally proposed, by a vote of one fifth of the members of the committee, or by the decision of the Government.

There are special procedures for the passage of laws granting emergency powers, the annual law incorporating EU law, annual financial laws (such as the budget), and the passage of laws under urgency.[11]

Once the bill has been approved in the same form by both houses of Parliament, it is sent to the President of the Republic, who must promulgate it within one month or send it back to Parliament for renewed debate with a written justification. If after the renewed debate the bill is approved by Parliament again, the President of the Republic is constitutionally required to promulgate it. Once it has been promulgated, the law is published in the official gazette by the Ministry of Justice and enters into force after the vacatio legis (15 days unless otherwise specified).

Amendments to the Constitutional and constitutional laws

The rigidity of the Constitution is ensured by the special procedure required to amend it. With the same procedure, Parliament can adopt a constitutional law, which is a law with the same strength as the Constitution.

Article 138 of the Constitution provides for the special procedure through which the Parliament can adopt constitutional laws (including laws to amend the Constitution), which is a variation of the ordinary legislative procedure.[12] The ordinary procedure to adopt a law in Italy requires both houses of parliament to approve the law in the same text, with a simple majority (i.e. the majority of votes cast). Constitutional laws start by following the same procedure. However, after having been approved for the first time, they need to be voted for by both houses a second time, which can happen no sooner than three months after the first. In this second reading, no new amendments to the bill may be proposed: the bill must be either approved or rejected in its entirety.

The constitutional law needs to be approved by at least a majority of MPs in each house (absolute majority) in its second reading. Depending on the results of this second vote, the constitutional law may then follow two different paths.

- If the bill is approved by a qualified majority of two-thirds of members in each house, it can be immediately promulgated by the President of the Republic and become law.

- If the bill is approved by a majority of members in each house, but not enough to reach the qualified majority of two-thirds, it does not immediately become law. Instead, it must first be published in the Official Gazette (the official journal where all Italian laws are published). Within three months after its publication, a constitutional referendum may be requested by either 500,000 voters, five regional councils, or one-fifth of the members of a house of parliament. If no constitutional referendum has been requested after the three months have elapsed, the bill can be promulgated and becomes law.

Reviewing and guiding the executive

In addition to its legislative functions, the Parliament also reviews the actions of the Government and provides it with political direction.

Parliament exercises its review function by means of questions and inquests. Questions consist of a written question directed to the Government, asking whether a certain claim is true, whether the Government is aware of it, and whether the Government is taking any action about it. The response can be given by the relevant Government minister, by the chairperson of the relevant ministry, or by an undersecretary. It may be given in writing or delivered to the parliament orally. The member who asked the question can respond to say whether or not the answer is satisfactory. In injunctions, a fact is noted with a request for the reasons for the conduct of the Government and its future intentions. The process is done by writing. If the member who filed the injunction is not satisfied with the response, they can present a motion to hold a debate in the Parliament.

The provision of political direction embodies the relationship of trust which is meant to exist between Parliament and the Government. It takes the form of confidence votes and votes of no confidence. These can be held concerning the entire Government or an individual minister. Other means of providing political direction include motions, resolutions, and day-orders giving instruction to the Government.

Inquests

Under Article 82 of the Constitution, "each chamber can undertake inquests into matters of public interest. For this purpose, they should appoint a committee formed so that it conforms to the proportions of the various parliamentary groups." In order to fulfill its function as the ordinary organ through which popular sovereignty is exercised, Parliament can employ the same investigative and coercive instruments as the judiciary in these inquests.

Joint sessions

The Parliament meets and votes in joint session (Italian: Camere in seduta comune) for a set of functions explicitly established by the Constitution. Article 55.2 specifies that these functions are entrenched and cannot be altered.

Joint sessions take place in the building of the Chamber of Deputies at Palazzo Montecitorio and are presided over by the President of the Chamber of Deputies ex officio.[13] In this way, the drafters of the Constitution intended to establish an equilibrium with the power of the President of the Senate to exercise the functions of the President of the Republic when the latter is indisposed.

Joint sessions take place for the following matters explicitly established by the Constitution:[14]

- to elect the President of the Republic (in this case, 58 regional delegates are added to the assembly). For the first three votes, a two-thirds majority is required to elect the president. If these fail, subsequent votes only require a simple majority.[15]

- to receive the President of the Republic's oath of office on election.[16]

- to vote on the impeachment of the President of the Republic[17] (an accusation of "high treason or attack to the Constitution"; this has never happened). This only requires a simple majority.

- to elect one third of the elected members of the High Council of the Judiciary.[18] For the first two votes, election requires a three-fifths majority of the delegates; subsequent votes require a three-fifths majority of voting members (i.e. excluding abstentions).[19]

- to elect five of the fifteen judges of the Constitutional Court.[20] The first three votes require a two-thirds majority; subsequent votes require only a three-fifths majority.[21]

- to vote on the list of 45 citizens from which sixteen lay members of the Constitutional Court are to be drawn in case of impeachment against the President of the Republic.[20] The same voting system is used as for the election of the judges of the Consititutional Court.

There is debate among legal scholars about whether the Parliament in joint session can make its own standing orders. Most scholars think it can, by analogy with the regulation of the Senate in article 65, which explicitly foresees such action.[22]

Prerogatives

The Chambers of the Italian Parliament enjoy special prerogatives to guarantee their autonomy with respect to other parts of Government:

- Regulatory autonomy: the chambers regulate and approve the regulations which govern their internal affairs autonomously.

- Financial autonomy: the chambers decide autonomously the amount of resources they require for carrying out their functions. The Court of Audit has no jurisdiction over this.[23]

- Administrative autonomy: Each chamber is in charge of the organisation of its own administrative facilities and the employment of its own officials (exclusively through a national public competition).

- Inviolability of the site: law enforcement officials can enter the parliament buildings only with the permission of the members of the respective chambers and they may not be armed.

Autodichia

In some matters (e.g. employment disputes) the Italian Parliament acts as its own judicial authority (without using external courts), which is referred to as "autodichia" (self-judging).[24] In order no. 137 of 2015 of the Italian Constitutional Court,[25] which agreed to rehear the appeal in the Lorenzoni case,[26] which had been dismissed the year before, it was stated that autodichia might be found in violation of the independence of the judiciary.

Parliamentary immunity

The constitution defines "Parliamentary status" in articles 66, 67, 68 and 69.

Article 67 ("Prohibition on imperative mandate) states that "every member of parliament represents the nation and performs their functions without limitation by a mandate." The members are considered to receive a general mandate from the whole electorate, which cannot be revoked by the initiative of the individual electoral district which elected them, nor by their political party. This general mandate is not subject to judicial review, only political review through constitutionally defined methods (mainly elections and referenda).

Article 68 lays down the principles of immunity (insindacabilità) and inviolability (inviolabilità), stating that "the members of parliament cannot be called to account for the opinions they express or the votes that they cast in the exercise of their functions" and that "without the permission of the chamber to which they belong, no member of parliament can be subjected to a body search or a search of their home, nor can they be arrested or otherwise stripped of their personal freedom, or imprisoned, except in the execution of a final court judgement or if caught in the act of a crime for which it is compulsory to arrest someone caught in the act. An analogous standard is required in order to put members of parliament under any form of surveillance." Neither immunity nor inviolability are prerogatives of individual parliamentarians; they are intended to protect the free exercise of Parliament's functions against judicial interference, which occurred in earlier regimes when the judiciary was under Government control and was not autonomous. There is controversy with respect to the principle of immunity about what statements are expressed in the member's parliamentary role and the Constitutional Court distinguishes between political activities and parliamentary activities, and even with respect to the latter, distinguishes between activities which are immune and activities which are not immune because they contradict other constitutional principles and rights. The principle of inviolability results from Constitutional Law #3 of 1993, which revoked the earlier system of "authorisation to proceed" (autorizzazione a procedere) for convictions in cases with defined sentences.

Finally, article 69 states that "members of parliament receive compensation set down by the law," thereby affirming that parliamentarians must receive compensation and cannot renounce that compensation. This reverses the principle laid down in the Albertine Statute, which was the opposite, and is linked to the principle of equality (article 3) and the prohibition on imperative mandate (article 67).

Electoral system

Election of the Senate

The election of the Senate is still regulated by Law n. 270 of 21 December 2005, which however was judged to be partly unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in December 2013.[27] It introduces a regional based proportional representation system corrected with a majority bonus, with the following characteristics:[28]

- The election uses a closed list system: seats are assigned based on the order of the candidates in the party list.

- Parties can run in coalitions. To be entitled to a share of seats, parties or coalitions need to pass an elaborate system of election threshold, based on regional votes: coalitions need to have at least 20% of the votes and a list with at least 3% of the votes; parties or lists need at least 8% of the votes (lowered to 3% if the party or list is part of a coalition that meets the threshold).

- In each Region, except for three, at least 55% of the seats are assigned to the coalition or list which received the most votes. The Aosta Valley elects one senator, so it uses a first past the post system. Molise elects two senators with a proportional system (no majority bonus). Trentino-South Tyrol uses a mixed member proportional system: it elects 6 senators in first past the post constituencies, plus one senator based on regional proportional voting.

The Constitutional Court found the majority bonus and the lack of preference voting of the electoral law to be unconstitutional. With those provisions now null and void, the voting system for electing the Senate became an open list proportional representation system, while still retaining the possibility to form coalitions and the high election thresholds.[29]

Election of the Chamber of Deputies

The election of the Chamber of Deputies is regulated by Law n. 52 of 6 May 2015,[30] which however was judged to be partly unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court in January 2017. It introduces a two-round system based on party-list proportional representation, with the following characteristics:[31]

- The party or list which gains 40% or more of the votes during the first turn gains 340 seats (out of 630). The remaining 290 seats are proportionally distributed among the other parties which pass a 3% election threshold.

- If no party manages to gain 40% or more of the votes on the first round, a second round of voting is held between the two parties which received the most votes. The winner of the second round gains 340 seats.

- The national territory is divided into 20 electoral districts, further divided into 100 multi-member constituencies, except in the Aosta Valley and Trentino-South Tyrol Regions, where constituencies are single-member.

- The first elected candidate for each list is always the first candidate on the list (capolista). Starting from the second candidate, seats are assigned according to open list preferences: each voter can express two preferences, but they must be for candidates of different genders.

The law, which came into force on 1 July 2016, has yet to be used for an election. In January 2017, the Constitutional Court judged the majority bonus in the second round (but not the one in the first round, subject to a threshold of 40% of the votes), as well as the ability of the capolista running in multiple constituencies to choose in respect of which constituency they are elected, to be unconstitutional.

Overseas constituencies

The Italian Parliament is one of the few legislatures in the world to reserve seats for those citizens residing abroad. There are twelve such seats in the Chamber of Deputies and six in the Senate.[32]

Membership

Senate

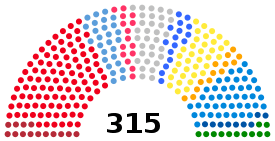

The current membership of the Italian Senate, following the latest political elections of 24 and 25 February 2013:

| Coalition | Party | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pier Luigi Bersani: Italy. Common Good |

Democratic Party (PD) | 111 | ||

| Left Ecology Freedom (SEL) | 7 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 2 | |||

| Trentino Tyrolean Autonomist Party (PATT) | 1 | |||

| Union for Trentino (UPT) | 1 | |||

| The Megaphone – Crocetta List (IM-LC) | 1 | |||

| Total | 123 | |||

| Silvio Berlusconi: Centre-right coalition |

The People of Freedom (PdL) | 98 | ||

| Lega Nord (LN) | 18 | |||

| Great South (GS) | 1 | |||

| Total | 117 | |||

| Beppe Grillo: Five Star Movement (M5S) | 54 | |||

| Mario Monti: With Monti for Italy | 19 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 1 | |||

| Aosta Valley coalition (VdA) | Valdostan Union (UV) | 1 | ||

| Total | 315 | |||

Chamber of Deputies

| Coalition | Party | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pier Luigi Bersani: Italy. Common Good |

Democratic Party (PD) | 297 | ||

| Left Ecology Freedom (SEL) | 37 | |||

| Democratic Centre (CD) | 6 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 5 | |||

| Total | 345 | |||

| Silvio Berlusconi: Centre-right coalition |

The People of Freedom (PdL) | 98 | ||

| Lega Nord (LN) | 18 | |||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 9 | |||

| Total | 125 | |||

| Beppe Grillo: Five Star Movement (M5S) | 109 | |||

| Mario Monti: With Monti for Italy |

Civic Choice (SC) | 37[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Union of Christian and Centre Democrats (UDC) | 8 | |||

| With Monti for Italy (SC abroad) | 2 | |||

| Total | 47 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 2 | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | 1 | |||

| Aosta Valley coalition (VdA) | Edelweiss (SA) | 1 | ||

| Total | 630 | |||

As illustrated by the bars above, the Bersani-led coalition won the plurality in the nationwide election with a 0.4% lead over the nearest coalition, and thus - as defined by the Italian election law - was granted a majority bonus equal to an automatic 55% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parliament of Italy. |

- Constituent Assembly of Italy

- Italian Parliament (1928–1939)

- Politics of Italy

- Prime Minister of Italy

- Roman Senate

Notes

- ↑ Incl. the Union for Trentino (UPT) party leader Lorenzo Dellai, who decided not to submit his own party list for the Monti-coalition, but opted to be a direct part of the Civic Choice list.[33][34]

References

- ↑ Article 56 of the Constitution

- ↑ Articles 57, 58, and 59 of the Constitution

- ↑ DISPOSIZIONI GENERALI IN MATERIA DI CERIMONIALE E DISCIPLINA DELLE PRECEDENZE TRA LE CARICHE PUBBLICHE. (in Italian)

- ↑ Constitutional Law n.2 of 9 February 1963.

- ↑ Article 59 of the Constitution.

- 1 2 Article 56 of the Constitution.

- 1 2 Article 58 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Article 84 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Against the mingling of confidence vote and legislative process see (in Italian) D. Argondizzo and G. Buonomo, Spigolature intorno all’attuale bicameralismo e proposte per quello futuro, in Mondoperaio online, 2 aprile 2014.

- ↑ Article 72 of the Constitution

- ↑ ((https://www.academia.edu/2462641/Esame_parlamentare_dei_documenti_finanziari_in_sessione_di_bilancio))

- ↑ Bin, Roverto and Pitruzella, Giovanni (2008), Diritto costituzionale, G. Giappichelli Editore, Turin, p. 322.

- ↑ Article 63 of the Constitution

- ↑ Article 55 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Article 83 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Article 91 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Article 90 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Article 104 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Law of 24 March 1958, article 22, n. 195

- 1 2 Article 135 of the Constitution.

- ↑ Constitutional Law of 22 November 1967, article 3, n. 2

- ↑ Paolo Caretti e Ugo De Siervo, Istituzioni di diritto pubblico, Torino, Giappichelli Editore, pag. 239. In the same chapter, the authors stress that the convention which drafted the constitution considered giving more powers to the joint sessions, but this was rejected in the hope of maintaining the bicameral system.

- ↑ Judgement. no. 129/1981

- ↑ According to the European Court of Human rights, in Italy "«autodichia», c'est-à-dire l'autonomie normative du Parlement" (judgement 28 April 2009, Savino and others v. Italy).

- ↑ http://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2015/07/07/consulta-ammissibile-il-conflitto-di-attribuzione-tra-poteri-dello-stato/1853996/

- ↑ See Giampiero Buonomo, Lo scudo di cartone, 2015, Rubbettino Editore, p. 224 (§ 5.5: La sentenza Lorenzoni), ISBN 9788849844405.

- ↑ http://www.cortecostituzionale.it/actionSchedaPronuncia.do?anno=2014&numero=1

- ↑ https://www.senato.it/1013?testo_generico=4&voce_sommario=58

- ↑ http://www.corriere.it/referendum-costituzionale-2016/notizie/legge-elettorale-italicum-camera-consultellum-senato-c7b7e3d8-bbac-11e6-a857-3c2e3af6f0b6.shtml

- ↑ (in Italian) LEGGE 6 maggio 2015, n. 52.

- ↑ http://www.internazionale.it/notizie/2016/10/05/italicum-riforma-elettorale

- ↑ "Presentazione delle candidature per la circoscrizione estero" [Submission of nominations for the constituency abroad]. Ministry of the Interior of Italy.

- ↑ "List Monti in Trentino: Lorenzo Dellai and candidates from Societa' Civile" (in Italian). l'Adige. 9 January 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Regional elections, the idea of coalition wins" (in Italian). l'Adige. 26 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

Further reading

- Gilbert, Mark (1995). The Italian Revolution: The End of Politics, Italian Style?.

- Koff, Sondra; Stephen P. Koff (2000). Italy: From the First to the Second Republic.

- Pasquino, Gianfranco (1995). "Die Reform eines Wahlrechtssystems: Der Fall Italien". Politische Institutionen im Wandel.

External links

- (in Italian) Official website

- Election resources for the Parliament