Paris in the 17th century

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Paris |

|

| See also |

|

|

Paris in the 17th century was the largest city in Europe, with a population of half a million, matched in size only by London. It was ruled in turn by three monarchs; Henry IV, Louis XIII, and Louis XIV, and saw the building of some of the city's most famous parks and monuments, including the Pont Neuf, the Palais Royal, the newly joined Louvre and Tuileries Palace, the Place des Vosges, and the Luxembourg Garden. It was also a flourishing center of French science and the arts; it saw the founding of the Paris Observatory, the French Academy of Sciences and the first botanical garden in Paris, which also became the first park in Paris open to the public. The first permanent theater opened, the Comédie-Française was founded, and the first French opera and French ballets had their premieres. Paris became the home of the new Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, and of some of France's most famous writers, including Pierre Corneille, Jean Racine, La Fontaine and Moliere. Urban innovations for the city included the first street lighting, the first public transport, the first building code, and the first new aqueduct since Roman times.

Paris under Henry IV

At the end of the 16th century, Paris was the last fortress of the besieged Catholic League, defended by the soldiers of the King of Spain and the fervently Catholic population. The royalist army of Henry IV had defeated the Catholic League on the battlefield, and Henry's soldiers were bombarding Paris from the heights of Montmartre and Montfaucon, but, lacking heavy artillery he could not break through the massive walls of the city. He decided instead upon a dramatic gesture to win over the Parisians; on July 25, 1593, at the Abbey of Saint-Denis, Henry IV formally renounced his Protestant faith. In the following weeks, the support for the Catholic League melted away. The Governor of Paris and the Provost of the merchants secretly joined Henry's side, and on March 2 the leader of the League, Charles de Mayenne, fled the city, followed by his Spanish soldiers. On March 22, 1594, Henry IV triumphantly entered the city, ending a war that had lasted for thirty years.[1]

Once established in Paris, Henry worked to reconcile himself with the leaders of the Catholic Church. He decreed toleration of the Protestants with the Edict of Nantes, and imposed an end to the war with Spain and Savoy. To govern the city, he named Francois Miron, a loyal and energetic administrator, as the new lieutenant of the Chatelet (effectively the chief of police) from 1604 until 1606, and then as Provost of the Merchants, the highest administrative post, from 1606 until 1612. He named Jacques Sanguin, another effective administrator, to be Provost of the Merchants from 1606 to 1612.[2]

Paris had suffered greatly during the wars of religion; a third of the Parisians had fled; the population was estimated to be 300,000 in 1600.[3] Many houses were destroyed, and the grand projects of the Louvre, the Hôtel de Ville, and the Tuileries Palace were unfinished. Henry began a series of major new projects to improve the functioning and appearance of the city, and to win over the Parisians to his side. The Paris building projects of Henry IV were managed by his forceful superintendent of buildings, a Protestant and a general, Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully.[4]

Henry IV recommenced the construction of the Pont Neuf, which had been begun by Henry III in 1578, but had stopped during the wars of religion. It was finished between 1600 and 1607, and was the first Paris bridge without houses and with sidewalks. Near the bridge, he built La Samaritaine (1602–1608), a large pumping station which provided drinking water, as well as water for the gardens of the Louvre and the Tuileries Gardens.

Henry and his builders also decided to add an innovation to the Paris cityscape; three new residential squares, modeled after those in Italian Renaissance cities. On the vacant site of the old royal residence of Henri II, the Hôtel des Tournelles, he built an elegant new residential square surrounded by brick houses and an arcade. It was built between 1605 and 1612, and was named Place Royale, renamed Place des Vosges in 1800. In 1607, he began work on a new residential triangle, Place Dauphine, lined by thirty-two brick and stone houses, near the end of the Île de la Cité. A third square, Place de France, was planned for a site near the old Temple, but was never built.[5]

Place Dauphine was Henry's last project for the city of Paris. The more fervent factions of the Catholic hierarchy in Rome and in France had never accepted Henry's authority, and there were seventeen unsuccessful attempts to kill him. The eighteenth attempt, on May 14, 1610 by François Ravaillac, a Catholic fanatic, while the King's carriage was blocked in traffic on rue de la Ferronnerie, was successful. Four years later, a bronze equestrian statue of the murdered king was erected on the bridge he had constructed at the Île de la Cité western point, looking toward Place Dauphine.[6]

Paris under Louis XIII

Louis XIII was a few months short of his eighth birthday when his father was assassinated. His mother, Marie de' Medici, became Regent and ruled France in his name. She retained many of the ministers of Henry IV, but dismissed the most talented, Sully, because of his abrasive personality. She filled the royal council instead with nobles from her native Florence, including Concino Concini, the husband of one of her ladies in waiting, Leonora Dori, who served the superstitious Queen by performing exorcisms and white magic to undo curses and black magic. Concini became head of the royal council.

Marie de' Medicis decided to build a residence for herself, the Luxembourg Palace, on the sparsely-populated left bank. It was constructed between 1615 and 1630, and modelled after the Pitti Palace in Florence. She commissioned the most famous painter of the period, Peter Paul Rubens, to decorate the interior with huge canvases of her life with Henry IV (now on display in the Louvre). She ordered the construction of a large Italian Renaissance garden around her palace, and commissioned a Florentine fountain-maker, Tommaso Francini, to create the Medici Fountain. Water was scarce in the Left Bank, one reason that part of the city had grown more slowly than the Right Bank. To provide water for her gardens and fountains, Marie de Medicis had the old Roman aqueduct from Rungis reconstructed. Thanks largely to her presence on the left bank, and the availability of water, noble families began to build houses on the left bank, in a neighborhood that became known Faubourg Saint-Germain. In 1616, she created another reminder of Florence on the right bank; the Cours la Reine, a long tree-shaded promenade along the Seine west of the Tuileries Gardens.

Louis XIII entered his fourteenth year in 1614, and was officially an adult, but his mother and her favorite, Concini, refused to allow him to lead the Royal Council. On April 24, 1617, Louis had his captain of the guards assassinate Concini at the Louvre. Concini's wife was charged with sorcery, beheaded and then burned at that stake on the Place de Greve. Concini's followers were chased from Paris. Louis exiled his mother to the Château de Blois in the Loire Valley. Louis made his own favorite, Charles d'Albert, the Duke of Luynes, the new head of the council, and launched a new campaign to persecute the Protestants. The Duke of Luynes died during an unsuccessful military campaign against the Protestants in Montauban.[5]

Marie de' Medici managed to escape from her exile in the Château de Bois, and was reconciled with her son. Louis tried several different heads of government before finally selecting the Cardinal de Richelieu, a protege of his mother, in April 1624. Richelieu quickly showed his military skills and gift for political intrigue by defeating the Protestants at La Rochelle in 1628 and by executing or sending into exile several high-ranking nobles who challenged his authority.[7]

In 1630 Marie de' Medici quarreled again with Richelieu, and demanded that her son choose between Richelieu or her. For a day (called by historians the "Day of the dupes") it appeared that she had won, but the next day Louis XIII invited Richelieu to the château de Vincennes and gave him his full support. Marie de' Medici was exiled to Compiegne, then went to live in exile in Brussels, Amsterdam and Cologne, where she died in 1642. Richelieu turned his attention to completing and beginning new projects for the improvement of Paris. Between 1614 and 1635, four new bridges were built over the Seine; the Pont Marie, the Pont de la Tournelle, the Pont au Double, and the Pont Barbier. Two small islands in the Seine, the Île Notre-Dame and the Île-aux-vaches, which had been used for grazing cattle and storing firewood, were combined to make the Île Saint-Louis, which became the site of the splendid hôtels particuliers of Parisian financiers.[8]

Louis XIII and Richelieu continued the rebuilding of the Louvre project begun by Henri IV. In the center of the old medieval fortress, where the great round tower had been, he created the harmonious cour carrée, or square courtyard, with its sculpted facades. In 1624 Richelieu began construction of a palatial new residence for himself in the center of the city, the Palais-Cardinal, which on his death was willed to the King and became the Palais-Royal. He began by buying a large mansion, the Hôtel de Rambouillet, to which he added an enormous garden, three times larger than the present Palais-Royal garden, ornamented with a fountain in the center, flowerbeds and rows of ornamental trees, and surrounded by arcades and buildings.[9] In 1629, once the construction of the new palace was underway, land was cleared and construction of a new residential neighborhood began nearby, the quartier Richelieu, near the Porte Saint-Honoré. Other members of the Nobility of the Robe (mostly members of government councils and the courts) built their new residences in the Marais, close to the Place Royale.[7]

Richelieu helped introduce a new religious architectural style into Paris, inspired by the famous churches in Rome, particularly the church of the Jesuits, and the Basilica of Saint Peter. The first façade built in the Jesuit style was that of the church of Saint-Gervais (1616); the first church entirely built in the new style was Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, on rue Saint-Antoine in the Marais between 1627-1647. The hearts of both Louis XIII and Louis XIV were interred there.[10]

Richelieu also built a new chapel for the Sorbonne, for which he had been the proviseur, or head of the college. It was constructed between 1635 and 1642. The dome was inspired by dome of Saint Peter's in Rome, which also inspired the domes at the churches of Val-de-Grace and Les Invalides. The plan was taken from another Roman church, San Carlo ai Catinari. When Richelieu died, the church became his final resting place.

During the first part of the regime of Louis XIII Paris prospered and expanded, but the beginning of French involvement the Thirty Years' War against the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs in 1635 brought heavy new taxes and hardships. The French Army was defeated by the Habsburg-ruled Spanish on August 15, 1636, and for several months a Spanish army threatened Paris. The King and Richelieu became increasingly unpopular with the Parisians. Richelieu died in 1642, and Louis XIII six months later in 1643. The playwright and poet Pierre Corneille described the feelings of Parisians toward the King and his government in a sonnet written shortly after the King's death; "In his name, ambition, pride, audacity and avarice made our laws: and while He was himself the most just of Kings, injustice ruled throughout his reign."[7]

Paris under Louis XIV

Turmoil and the Fronde

Richelieu died in 1642, and Louis XIII in 1643. At the death of his father, Louis XIV was only five years old, and his mother, Anne of Austria, became Regent. Richelieu's successor, Cardinal Mazarin, decreed a series of heavy new taxes upon the Parisians to finance the ongoing war. A new law in 1644 required those who had built homes close to the city walls to pay heavy penalties; in 1646 new tax was imposed on the middle-class to finance a loan to the state of 500,000 pounds, and taxes were imposed on all fruits and vegetables brought into the city. In 1647 a new law required that those who had built homes on property officially belonging to the King would have to re-purchase the rights to the land. In 1648 Mazarin informed the noble members of three of the highest civil councils in the city, the Grand Council, the Chambre des comptes and the Cour des Aides that they would not be paid any salary for the next four years. These measures caused a rebellion within the Parlement of Paris, which was not an elected assembly but a high court made up of prominent noblemen. On May 13, 1648, the Parlement called a meeting in the Chambre Saint-Louis, the main hall of the Palace on the île de la Cité, to "reform the abuses of the State".[11]

Faced with the united opposition of the leaders of Paris, Mazarin backed down and accepted many of their proposals, and waited for an opportunity to strike back. The victory of the French army led by Louis de Bourbon, Prince of Condé over the Spanish at the Battle of Lens gave him the opportunity he needed. An arranged a special mass at the Cathedral of Notre Dame, with the presence of the young King, to celebrate the victory, and brought soldiers into the city to line the street for the procession before the ceremony. As soon as the ceremony at Notre-Dame concluded, Mazarin had three prominent members of the Parlement arrested.

When news of the arrests spread around Paris, riots broke out in the streets, and more than twelve hundred barricades were erected on the Île de la Cité, near the Place de Greve, les Halles, around the University, and in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. There were several violent confrontations in the streets between soldiers and the Parisians. The leaders of the Parlement were received at the Palais-Royal, where Anne of Austria and the young King were living, and she agreed, after some hesitation, to release the imprisoned member of the Parlement.

This was the beginning of the Fronde, a long struggle between Mazarin and the Parlement of Paris and its supporters, and then between Mazarin and two princes of the royal family. The signing of the Peace of Westphalia on May 15, 1648, ending the Thirty Years' War, allowed Mazarin to bring his army, led by the Prince of Condé, back toward Paris. On the night of 5–6 January, Mazarin, the Regent and the young king were smuggled out of Paris to the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. The Parlement declared Mazarin a public enemy and called upon the Parisians to take up arms. The arrival of the royal army under de Condé put down the first uprising, but the struggle between Mazarin and the Parlement continued. On the night of February 6–7, Mazarin, in disguise, left Paris for Le Havre. On February 16, Condé, the commander of the royal army, changed sides and demanded to be the leader of the Fronde. The Fronde quickly split into rival factions, while Mazarin did not have the funds to raise an army to defeat it. The standoff between Mazarin and the Fronde continued from 1648 until 1653. At times, the young Louis XIV was held under virtual house arrest in the Palais-Royal. He and his mother were forced to flee the city twice to the royal château at Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

In 1652, Mazarin made the error of enlisting seven to eight thousand German mercenaries with his own money to fight against the French army. The Fronde rose again, this time led by two prominent nobles, the Prince de Condé, Gaston, Duke of Orléans, the Governor of Paris and the younger brother of the King, against Mazarin. At the beginning of May, the royal army of Turenne defeated the Frondeurs under Condé at Étampes, not far from Paris; they fought again at Saint Denis April 10 and 12. The Parlement refused to allow Condé and his soldiers into the city. On July 2, Condé's soldiers fought the royal army just outside the city, beneath the walls of the Bastille, and were defeated. Condé managed to bring the remains of his army into Paris. He summoned the Parlement and leading merchants and clergy, and demanded to be recognized as the leader of the city. The leaders of the Parlement and the merchants of Paris, along with representatives of the clergy, assembled at the Hôtel de Ville and rejected Condé's proposal; they simply wanted the departure of Mazarin. The soldiers of Condé, furious, attacked the assembly, killing some of the members, further alienating the Parisians.[12]

On August 19 Mazarin withdrew to Bouillon in the Ardennes and continued his intrigues to win back Paris from there. Rising prices and the scarcity of food in Paris made the government of Frondeurs more and more unpopular. On September 10, Mazarin encouraged the Parisians to take up arms against Condé. On September 24, a large demonstration took place outside the Palais-Royal, demanding the return of the King. Gaston d'Orleans changed sides, turning against Condé. On September 28, the leaders of Paris sent a delegation to the King asking him to return to the city, and refused to pay or feed the soldiers of Condé camped in the city. Condé abandoned Paris on October 14 and took refuge in the Spanish Netherlands. On October 22 the young King, at the Louvre, issued a decree forbidding the Parlement of Paris to interfere in affairs of state and the royal finances. Mazarin, victorious, returned to Paris on February 3, 1653 and took charge once again of the government.[13]

"The new Rome"

As a result of the Fronde, Louis XIV had a profound lifelong distrust of the Parisians. He moved his Paris residence from the Palais-Royal to the more secure Louvre: then, in 1671, he moved the royal residence out of the city to Versailles, and came into Paris as seldom as possible.[14]

While he disliked the Parisians, Louis XIV wanted to give Paris a monumental grandeur that would make it the successor to Ancient Rome. The King named Jean-Baptiste Colbert as his new Superintendent of Buildings, and Colbert began an ambitious building program. To make his intention clear Louis XIV organised a carrousel festival in the courtyard of the Tuileries in January 1661, in which he appeared, on horseback, in the costume of a Roman Emperor, followed by the nobility of Paris. Louis completed the Cour carrée of the Louvre and built a majestic row of columns along its east façade (1670). Inside the Louvre his architect Louis Le Vau and his decorator Charles Le Brun created the Gallery of Apollo, the ceiling of which featured an allegoric figure of the young king steering the chariot of the sun across the sky. He enlarged the Tuileries Palace with a new north pavilion, built a magnificent new theater attached to the palace, and had André Le Nôtre, the royal gardener, remodel the gardens of the Tuileries into a French formal garden. But another ambitious project, an exuberant design by Bernini for the eastern facade, was never built; it was replaced by a more severe and less expensive colonnade by Claude Perrault, whose construction proceeded very slowly due to a lack of funds. Louis turned his attention more and more to Versailles.[15]

On February 10, 1671, Louis departed Paris and made his permanent residence in Versailles. In the remaining forty-three years of his reign, he visited Paris just twenty-four times for official ceremonies, usually for no longer than twenty-four hours. While he built new monuments to his glory, the King also took measures to prevent any form of opposition to his will. On March 15, 1667, he named Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie to a new position, the Lieutenant General of Police, with the function of making the city work more efficiently, but also to suppress any opposition or criticism of the King. The number of policemen was quadrupled. Anyone who circulated a pamphlet or flyer critical of the King was subject to whipping, banishment and a sentence to the galleys. On 22 October the King revoked the edict of Nantes and its promised religious tolerance for Protestants; on the same day demolition of the Protestant church at Charenton began. Repression of dissident sects resumed.[16]

In his absence, his construction projects within Paris continued. Mazarin left funds in his will to build the Collège des Quatre-Nations (College of the Four Nations) (1662–1672), an ensemble of four baroque palaces and a domed church, to house sixty young noble students coming to Paris from four provinces recently attached to France (today it is the Institut de France). In the center of Paris, Colbert constructed two monumental new squares, Place des Victoires (1689) and Place Vendôme (1698). He built a new hospital for Paris, La Salpêtrière, and, for wounded soldiers, a new hospital complex with two churches, Les Invalides (1674). Of the two hundred million livres that Louis spent on buildings, twenty million were spent in Paris; ten million for the Louvre and the Tuileries; 3.5 million for the new royal Gobelins Manufactory and the Savonnerie, 2 million for Place Vendôme, and about the same for the churches of Les Invalides. Louis XIV made his final visit to Paris in 1704 to see Les Invalides under construction.[17]

The city continued to expand. In 1672 Colbert issued new lettres patent to enlarge the formal boundaries of the city to the site of the future wall built by Louis XVI in 1786, the Wall of the Farmers General. The nobility built its townhouses in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, which expanded as far as Les Invalides. Louis XIV declared that Paris was secure against any attack, and no longer needed its old walls. He demolished the main city walls, creating the space which eventually became the Grands Boulevards. To celebrate the destruction of the old walls, he built two small arches of triumph, Porte Saint-Denis (1672) and Porte Saint-Martin (1676).

The last years of the century brought more unhappiness for the Parisians. In 1688 the King's grand design to dominate Europe was challenged by the new Protestant King of England, William of Orange, King of England, and by a new coalition of European countries. The war brought more taxation for the Parisians. In 1692-93, the countryside was hit with poor harvests, causing widespread hunger in the city. In October 1693 the Lieutenant General of Police, La Reynie, built thirty ovens to bake bread for the poor of Paris. The bread was sold for two sous a loaf at the Louvre, the Place des Tuileries, the Bastille, the Luxembourg Palace, and on rue d'Enfer. Crowds pushed and fought for a chance to buy bread. The terrible conditions were repeated in the winter of 1693-94. One diarist, Robert Challes, wrote that, at the height of the famine, between fourteen and fifteen hundred people of both sexes and all ages were dying daily of hunger and disease at the Hôtel de Dieu hospital and on the streets outside. At the end of March 1694, Madame de Sévigné wrote to friends that she had to leave the city; "there is no longer any way to live in the middle of the air and misery we have here."[18]

The city grows

Paris in 1610 was roughly round, about five hundred hectares in area, and was divided by the Seine. It was possible to walk at a brisk pace from the north end of the city to the south, a distance of about three kilometers, in about half an hour.[19]

There were two main north-south streets through the city; one from Porte Saint Martin to Porte Saint-Jacques, which crossed the Seine on the Pont Notre-Dame, and a second wide street from Porte Saint-Denis to the Porte Saint-Michel, crossing the Pont au Change and the Pont Saint-Michel. There was a single main east-west axis, beginning at the Bastille in the east and ending at Porte Saint-Honoré in the west, via the rue Saint Antoine, rue des Balais, rue Roi-de-Sicilie, rue de la Verrerie, rue des Lombards, rue de la Ferronnerie, and finally rue Saint-Honoré.[19]

Between the main streets in the center of the city was a maze of narrow, winding streets, between wooden houses four or five stories high, dark at night and crowded and noisy during the day. At night, many of the streets were closed with large chains, kept in drums at the corners. They were dimly lit by a small number of oil lamps.

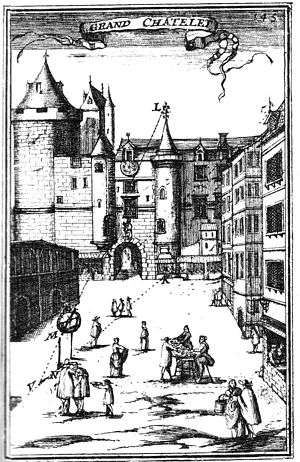

The royal residence was usually either the Louvre or the Château of Vincennes, just east of the city. The courts and royal administrative offices were in the old palace on the île de la Cité. The offices of the Provost of Paris, the King's governor, were in the Châtelet fortress, which also served as a prison. The city administration, run by the Provost of the Merchants, was in the Hôtel de Ville. The commercial center of the city was the river port, located mostly on the right bank between the Place de Greve and the Quai Saint Paul, not far from les Halles, the central market of the city. The colleges of the University occupied buildings on the side of Mount Saint-Genevieve, on the left bank.

On the right bank Paris was bordered by the wall begun in 1566 by Charles V, and later finished by Louis XIII in 1635. The wall was four meters high and two meters thick, and was reinforced by fourteen bastions ranging in size from 30 to 290 meters, and by a moat 25 to 30 meters wide, which was always kept full of water. Access to the city was by fourteen gates, each of which had a drawbridge over the moat. The gates were closed at night, usually between seven in the evening and five in the morning, with the schedule changing depending upon the season. The left bank did not have any recent fortifications; it was still protected by the old wall of King Philip Augustus.

The city wall did not mark the real edge of the city; there were some rural areas, with gardens and orchards, inside the walls, and there were many buildings and houses outside. Outside the walls there were a number of faubourgs, or suburbs; on the left bank, the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés was a virtual town, with its own fair and farms. The Faubourg of Saint-Jacques also on the left bank, was largely occupied by monasteries. The Faubourg Saint-Victor and Faubourg Saint-Marcel were crowded and growing. On the right bank were the Faubourgs of Saint-Honoré, Montmartre, Saint-Denis, du Temple, and the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, filled with artisans and workshops.

The edges of the growing city were not clearly defined until 1638, when the royal government drew a new line, which included the Faubourgs on both the right and left banks. On the left bank it reached south as far as the site of the future observatory, and included the all the area of the modern fifth and sixth arrondissements. On the right bank, the new boundary followed the line of new fortifications constructed by Louis XIII, along the modern boulevards de la Madeleine, des Capucines, des Italiens, Montmartre and Poissonniere.[20]

In 1670, Louis XIV declared that France was safe from attack and the walls were no longer necessary, and they were gradually replaced by boulevards lined by trees. The area of the city approximately doubled from what it had been early in the century, from 500 to about 1100 hectares. In 1674 the administrators marked the border more precisely, planting thirty-five marble or cut stone pillars and markers, twenty-two on the right bank and thirteen on the left. On the right bank, it began at the Place de la Concorde, passed by the sites of future Gare du Nord and de l'Est and reached almost to the modern avenue de la Republique and Place de la Nation, and came back to the river again at Bercy. On the left bank, the edges of the city were at rue de Tolbiac to the east and close to the modern Pont d'Alma to the west.[20]

Parisians

There was no official census of the city's population in the 17th century, but, using tax records, the amount of wheat consumed and church baptism records, modern historians estimate that it increased from about 300,000 in 1600 to 415,000 in 1637 to about 500,000 in about 1680. An account published in 1665 by Lemaire estimated that there were 23,000 houses in Paris, each inhabited by an average of twenty persons.[3]

Paris society was structured in a formal and rigid hierarchy. At the top were the nobles, known as personnes de qualité, meaning that they had no profession, unlike the artisans and merchants. They were subdivided into four categories; the highest were the titled nobility, gentlemen of the royal chamber and marshals of France, who had the titles of duke, marquis, comte, and baron. Just below them were those with the lesser rank of chevalier or seigneur.

The third level of nobles who held their title because of their function, as members of the highest bodies of state, the Parlement of Paris, the Grand Council, the Chambre des comptes, and the Cour des Aides. They were known as the Noblesse de la Grand Robe, the high nobility of the robe, because of the ceremonial costumes they wore. They usually purchased their titles, but once acquired they became hereditary. Below them were nobles of the petit robe, with high positions in the less important government bodies and less impressive ceremonial costumes. Below them, at the lowest edge of the nobility, were the ecuyers; some were from the ancient nobility, but many more recent arrivals, who had purchased a title or position at court. The members of the nobility of all levels usually had their own town houses, and most lived in the Marais, and later, on the newly created Île Saint-Louis and Faubourg Saint-Germain.

Just below the nobles and ecuyers but above the bourgeois were the notables, who were largely officials in the lesser government structures; officials in the treasury, royal accountants, and lawyers at the Parlement or other high courts. The notables but included prominent doctors and a few highly successful artists, including Claude Vignon and Simon Vouet. Just below the notables were those Parisians entitled to be called Maître; lawyers, notaries, and procureurs.

Below the notables and Maîtres was a far larger class, the Bourgeoisie or middle class, which was equally divided into categories. At the top were the Honorable hommes, a category which included the most successful merchants, artisans who had ten or fifteen employees, and a considerable number of successful painters, sculptors and engravers. Below them were the marchands or merchants, successful members of all the different professions. Twenty percent had their own shops. Below them were the maîtres and then the compagnons, craftsmen who had finished their apprenticeships. They usually lived in a single room, and were often not far above poverty.

Below the craftsmen and artisans was the largest class of Parisians; domestic servants, manual workers with no special qualifications, laborers, prostitutes, street sellers, rag-pickers, and a hundred other trades, with no certain income. They lived a very precarious existence.[21]

Beggars and the poor

A large number of Parisians were elderly, sick, or unable to work because of injuries. They were the responsibility of the Catholic church in each parish; an official of the parish was supposed to keep track of them and provide them with a small amount of money. In times of food shortages, such as the famine of 1629, or epidemics, the church was often unable to take care of all of the needs of those in the parish. In the case of vagabonds, those who came to Paris from outside the city but had no profession or home, there was no structure to take care of them.

There were a very large number of mendiants, or beggars, on the streets of Paris. One estimate put their number at forty thousand at the beginning of the reign of Louis XIII.[22] It was particularly feared that beggars from other cities would bring infectious diseases into the city. There was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the city in 1631, and there were frequent cases of leprosy, tuberculosis and syphilis in Paris. The Parisians learned that Geneva, Venice, Milan, Antwerp and Amsterdam had chosen to confine their beggars in hospitals created for that purpose. In 1611 the Bureau of the City ordered that the vagabonds should be taken off the streets. Those who could not show they were born in Paris were required to leave the city. Those who were native Parisians were put to work. When the news of the decree spread, many of the vagabonds and beggars quickly departed the city. The police rounded up the rest, confined the men who were able to work in a large house in the faubourg Saint-Victor, and the women and children in another large house in faubourg Saint-Marcel. Those with incurable illnesses or unable to work were taken to a third house in the faubourg Saint-Germain. They were supposed to awake at five in the morning and to work from 5:30 in the morning until 7:00 in the evening. The work consisted of grinding wheat, brewing beer, cutting wood, and other menial tasks; the women and girls over the age of eight were employed by sewing. The city judged the program a success, and acquired three large new buildings for the beggars. But within four years the program was abandoned; the work was poorly organized, and many of the beggars simply escaped.[22]

Charities - Renaudot and Vincent De Paul

The hardships and medical needs of the Paris poor were energetically addressed by one of the first Paris philanthropists, Theophraste Renaudot, a protegé of Cardinal Richelieu. Renaudot, a Protestant and a physician, founded the first weekly newspaper in France, La Gazette in 1631. Based on the newspaper, he founded the first employment bureau in Paris, matching employers and job-seekers. He organized public conferences on topics of public interest. He opened the first public pawn-shop in Paris, the mont-de-Pieté, so the poor could get money for belongings at reasonable rates. He also organized the first free medical consultations for the poor. This put him into opposition with the medical school of the University of Paris, which denounced him. After the death of his protectors, Richelieu and Louis XIII, the University had his medical license taken away, but eventually the University itself began to offer free medical consultations to the poor.[23]

Another pioneer in helping the Paris poor during the period was Vincent de Paul. As a young man, he had been captured by pirates and held as a slave for two years. When he finally returned to France, he entered the clergy and became chaplain to the French prisoners in Paris sentenced to the galleys. He had a talent for organization and inspiration; in 1629 he persuaded wealthy residents in the parish of Saint-Sauveur to fund and participate in charitable works for the poor of the Paris; with its success, he founded similar confréries for the parishes Saint-Eustache, Saint-Benoît, Saint-Merri and Saint Sulpice. In 1634, he took on a much more challenging task; providing assistance to the patients of the city's oldest and largest hospital, the Hôtel-Dieu, which was terribly overcrowded and under-funded. He persuaded wealthy women from noble families to prepare and distribute meat broth to the patients, and to help the patients with their needs. He instructed the women visiting the hospital to dress simply, and to speak to the poor with "humility, gentleness and cordiality." As time went on, he discovered that some of the wealthy women were delegating the servants to do the charitable work. In 1633 he founded a new charitable order for young women from more modest families, the Filles de la Charité, to carry on the work of feeding the poor. The young women, dressed in gray skirts and white cornettes, carried pots of soup to the poor of the neighborhoods. The first house of the order was at La Chapelle. Between 1638 and 1643, eight more houses of the order were opened to serve food to the poor.[24]

In 1638 he took on another ambitious project; providing food and care for the abandoned infants of Paris, the enfants trouvés. Four hundred unwanted babies were abandoned each year at the maison de la Couche, or maternity hospital, where most died in a very short time. There was only one nurse for four or five children, they were given laudanum to keep them from crying, and they were often sold to professional beggars, who used them to inspire pity and donations. In 1638 he persuaded wealthy Parisians to donate money to establish a home for found children on rue des Boulangers, near the porte Saint-Victor. De Paul and the sisters of the order made visits to churches to bring babies abandoned there at night to the new home. His work came to the attention of the King and Queen, who provided funding in 1645 to build a large new home for abandoned children near Saint-Lazare. De Paul died in 1660. In 1737, he was canonized as a saint by the Catholic Church.[25]

Thieves and the Courtyard of Miracles

Beside the beggars and the poor there was another underclass in Paris, composed of thieves. They often were expert in cutting the cords of the purses that wealthy Parisians carried around their necks and running off with them. They also sometimes pretended to be blind or lame, so they could attract charity from the Parisians. In the 17th century the most famous residence of such thieves was the Cour des Miracles, or Courtyard of Miracles, located between rue Montorgueil, the convent of the Filles-Dieu, and rue Neuve-Saint-Saveur, in the center of the city. It was named because its residents often appeared to blind or lame when on the streets but were perfectly whole when they returned home. It was described by the 18th century Paris historian Sauval,[26] based on his father's description of a visit to the Courtyard. "To enter there you have to descend a rather long slope, twisting and uneven. I saw a house half-buried in mud, crumbling with age and rot, which had only a fraction of its roof tiles, where however were lodged more than fifty families, with all their legitimate, illegitimate and undetermined children. I was assured that in this house and its neighbors there were more than five hundred large families living one on top of the other". The courtyard was a school of crime; the children were taught the best techniques for stealing purses and escaping, and were given a final examination of stealing a purse in a public place, such as the Cemetery of Saints-Innocents, under the scrutiny of their teachers. The Courtyard had its own King, laws, officers and ceremonies. The young inhabitants became expert in not only stealing, but also in simulating blindness, gangrene, rabies, and a wide variety of horrifying wounds and illnesses. In 1630 the city wanted to build a street through the Courtyard to connect rue Saint-Sauveur and rue Neuve-Saint-Sauveur, but the workmen were showered with rocks and assaulted and beaten by the residents of the Courtyard, and the project was abandoned.[27]

In 1668, shortly after being named Lieutenant-General of Police, de la Reynie decided to finally put an end to the Courtyard. He gathered one hundred fifty soldiers, gendarmes and sappers to break down the walls, and stormed the Courtyard, under a barrage or rocks from the residents. The inhabitants finally fled, and de la Reynie tore down their houses. The empty site was divided into lots and houses constructed. and is now part of the Benne-Nouvelle quarter. Sauval's description of the Courtyard was the source for Victor Hugo's courtyard of miracles in his novel Notre-Dame de Paris, though Hugo moved the period from the 17th century to the Middle Ages.[28]

City government

King Henry IV, who frequently was short of money, made one decision which was to have fateful consequences for Paris for two centuries to follow. At the suggestion of his royal secretary, Charles Paulet, he required the hereditary nobility of France to pay an annual tax for their titles. This tax, called "la Paullete" for the secretary, was so successful that it was expanded, so that wealthy Parisians who were not noble could purchase positions which gave them noble rank. When kings needed more money, they simply created more positions. By 1665, during the reign of Louis XIV, there were 45,780 positions of state. It cost 60,000 livres to become President of the Parlement of Paris, and 100,000 livres to be President of the Grand Council.[29]

During the reign of Louis XIII, the King's official representative in Paris was the Prévôt or Provost of Paris, who had his offices at the Châtelet fortress, but most of the day-to-day administration of the city was conducted from the recently finished Hôtel de Ville, under the direction of the Provost of the Merchants, elected by the bourgeois or upper-middle class of Paris. The status of bourgeois was granted to those Parisians who owned a house, paid taxes, had long been resident in Paris, and had an "honorable profession", which included magistrates; lawyers and those engaged in commerce, but excluded those whose business was providing food. Almost all the Provosts for generations came from among about fifty wealthy families. Elections were held for Provost every two years, and for the four positions of echevins, or deputies. After the election, held on August 16 of even-numbered years, the new Provost and new echevins were taken by carriage to the Louvre where they took an oath in person to the King and Queen.[29]

.jpg)

The position of Provost of the Merchants had no salary, but it had many benefits. The Provost received 250,000 livres a year for expenses, he was exempt from certain taxes, and he could import goods without duty into the city. He wore an impressive ceremonial costume of a velour robe, silk habit and a crimson cloak, and was entitled to cover his horse and his dress his household servants in a special red livery. He had his own honor guard, made up of twelve men chosen from the bourgeoisie, and he was always accompanied by four of these guards when about the city on official business.

The Provost was assisted by twenty-four conseillers de ville, a city council, who were chosen by the Provost and echevins, when there was an opening. Beneath the Provost and echevins there were numerous municipal officials, all selected from the bourgeoisie; two procureurs, three receveurs, a greffier, ten huissiers, a Master of Bridges, a Commissaire of the Quais, fourteen guardians of the city gates, and the Governor of the clock tower. Most of the positions of the Bureau of the City had to be purchased with a large sum of money, but once acquired, many of them could be held for life. Each of the sixteen quarters or neighborhoods of the city also had its own administrator, called a quarternier, who had eight deputies, called dizainiers. These positions had small salaries but were prestigious and came with generous tax exemptions.[30]

The Bureau of the City had its own courts and prison. The city officials were responsible for maintaining order in the city, fire safety, and security in the Paris streets. They assured that the gates were closed and locked at night, and that the chains were put up on the streets. They were responsible for the city's small armed force, the Milice Municipale and the Chevaliers de la guet, or night watchmen. The local officials of each quarter were responsible for keeping lists of the residents of every house in their neighborhoods, and also keeping track of strangers. They recorded the name of a traveler coming into the quarter, whether he stayed in a hotel, a cabaret with rooms, or a private home.[31]

During the second half of the 17th century, most of the independent institutions of the Parisian bourgeois had their powers taken away and transferred to the King. In March 1667 the King created the position of Lieutenant General of the police, with his office at the Chatelet, and gave the position to La Reynie, who held it for thirty years, from 1667 to 1697. He was responsible not only for the police, but also for supervising weights and measures, the cleaning and lighting of the streets, the supply of food to the markets, and the regulation of the corporations, all matters which previously had been overseen by the merchants of Paris. The last of the ancient corporations of Paris, the corporation of the water merchants, had its authority over river commerce taken away and given to the Crown in 1672. In 1681, Louis XIV took away almost all of the real powers of the municipal government. The Provost of the Merchants and the Echevins were still elected by the Bourgeois, but they had no more real power. Selling positions in the city government became an effective way to raise funds for the royal treasury. All other municipal titles below the Provost and Echevins had to be purchased directly from the King.[32]

Industry and commerce

At the beginning of the 17th century, the most important industry of the city was textiles; weaving and dyeing cloth, and making bonnets, belts, ribbons, and an assortment of other items of clothing. The dyeing industry was located in the Faubourg Saint-Marcel, along the River Bievre, which was quickly polluted by the workshops and dye vats along its banks. The largest workshops there, which made the fortunes of the families Gobelin, Canaye and Le Peultre, were dyeing six hundred thousand pieces of cloth a year in the mid-16th century, but, because of growing foreign competition, their output dropped to one hundred thousand pieces at the start of the 17th century, and the whole textile industry was struggling. Henry IV and Louis XIII observed that wealthy Parisians were spending huge sums to import silks, tapestries, glassware leather goods and carpets from Flanders, Spain, Italy and Turkey. They encouraged French businessmen to make the same luxury products in Paris.[33]

Royal manufacturies

With this royal encouragement, the financier Moisset launched an enterprise to make cloth woven with threads of gold, silver and silk. It failed, but was replaced by other successful ventures. The first tapestry workshop was opened, with royal assistance, in the Louvre, then at the Savonnerie and at Chaillot. The Gobelins' enterprise of dyers brought in two Flemish tapestry makers in 1601 and began to make its own tapestries in the Flemish style. Master craftsmen from Spain and Italy opened small enterprises to make high-quality leather goods. Workshops making fine furniture were opened by German craftsmen in the faubourg Saint-Antoine. A royal glass factory was opened 1601 in Saint-Germain-des-Prés to compete with Venetian glassmakers. A large factory was opened at Reuilly to produce and polish mirrors made by Saint-Gobain.[33]

Under Louis XIV and his minister of finance, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the royal manufacturies were expanded. The most skilled artisans in Europe were recruited and brought to Paris. In 1665 the enterprise of Hindret, located in the old château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne, produced the first French silk stockings. The Gobelins' workshops began to produce furniture for the royal residences as well as tapestries, while the Savonnerie Manufactory produced magnificent carpets for the royal palaces. The quality of the carpets, tapestries, furniture, glass and other products was unmatched; the problem was that it was nearly all destined for a single client, the King, and his new residence at Versailles. The royal manufacturies were kept going by enormous subsidies from the royal treasury.[34]

Craftsmen and corporations

The greatest resource of the Paris economy was its large number of skilled workers and craftsmen. Since the Middle Ages, each profession had had its own corporation, which set strict work rules and requirements to enter the profession. There were separate corporations for drapers, tailors, candle-makers, grocer-pharmacists, hat-makers, bonnet-makers, ribbon-makers, saddle-makers, stone carvers, bakers of spice breads, and many more. Doctors and barbers were members of the same corporation. Access in many professions was strictly limited to keep down competition, and the sons of craftsmen had priority. Those entering had to advance from apprentice to companion-worker to master worker, or maître. In 1637, there were 48,000 recorded skilled workers in Paris, and 13,500 maîtres.[35]

Luxury goods

The most important market for luxury goods was located on the Île-de-la-Cité, in the spacious gallery of the old royal palace, where it had been since at least the fourteenth century. The palace was no longer occupied by the King, and had become the administrative headquarters of the kingdom, occupied by the courts, the treasury, and other government offices. The small shops in the gallery sold a wide variety of expensive gowns, cloaks, perfumes, hats, bonnets, children's wear, gloves, and other items of clothing. Books were another luxury items sold there; they were hand-printed, expensively bound, and rare.

Clocks and watches were another important luxury good made in Paris shops. Access to the profession was strictly controlled; at the beginning of the 17th century, the guild of horlogers had twenty-five members. Each horloger was allowed to have no more than one apprentice, and apprenticeship lasted six years. By 1646, under new rules of the guild, the number of masters was limited to seventy-two, and the apprenticeship was lengthened to eight years. Most of the important public buildings, including the Hôtel de Ville and the Samaritaine pump, had their own clocks made by the guild. Two families, the Martinet and the Bidauld, dominated the profession; they had their workshops in the galleries of the Louvre, along with many highly skilled artists and craftsmen. Nearly all the clock and watchmakers were Protestants; when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, most of the horlogers refused to renounce their faith and emigrated to Geneva, England and Holland, and France no longer dominated the industry.[36]

Religion

For most of the 17th century Paris was governed by two Cardinals, Richelieu and Mazarin, and Paris was a fortress of the Roman Catholic faith, but it was subject to considerable religious turmoil within. In 1622, after centuries of being a bishopric under the control of the Archbishop of Sens, Paris was finally given its own Archbishop, Jean-François de Gondi, from a noble and wealthy Florentine-French family. His elder brother had been Bishop of Paris before him, and he was succeeded as Archbishop by his nephew; members of the Gondi family were the bishops and archbishops of Paris for nearly a century from 1570 to 1662. The hierarchy of the Church in Paris were all members of the higher levels of the nobility, with close connections to the royal family. As one modern historian noted, their dominant characteristics were "nepotism...ostentatious luxury, arrogance, and personal conduct far removed from the morality they preached."[37]

While the leaders of the church in Paris were more concerned with high political matters, the lower levels of the clergy were agitating for reform and more engagement with the poor. The Vatican had decided to create seminaries in Paris to give priests more training; the Seminary of Saint-Nicolas-de-Chardonnet was opened in 1611, the Seminary of Sant-Magliore in 1624, the Seminary of Vaugirard in 1641, before moving to Saint-Sulpice in 1642; and the Seminary of Bons-Enfants also opened in 1642. The seminaries became centers for reform and change. Thanks in large part to the efforts of Vincent de Paul, the parishes became much more actively involved in giving assistance to the poor and the sick, and giving schooling to young children. Confreries or brotherhoods of wealthy nobles, such as the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement, were formed, to assist the poor in Paris, to convert Protestants, and to send missions abroad to convert the inhabitants of new French colonies.

More than eighty religious orders also established themselves in Paris; sixty orders, forty for women and twenty for men, were established between 1600 and 1660. These included the Franciscans at Picpus in 1600, the Congregation of the Feuillants next to the gates of the Tuillieries palace in 1602; the Dominican Order at the same location in 1604, and the Carmelites from Spain in 1604 at Notre-Dame des Champs. The Capuchins were invited from Italy by Marie de' Medici, and opened convents in the faubourg Saint-Honoré, and the Marais, and a novitiate in the Faubourg Saint-Jacques. They became particularly useful, because, before the formation of a formal fire department by Napoleon, they were the principal fire-fighters of the city. They were joined by the Dominicans and by the Jesuits, who founded the College of Clermont of the Sorbonne, and built the opulent new Church of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis next to their headquarters on rue Saint-Antoine. The arrival of all these new orders, directed from Rome and entirely out of the control of the Archbishop of Paris, caused the alarm and eventually the hostility of the Paris church establishment.[38]

Followers of the church in Paris were divided by a new theological movement called Jansenism, founded by a Dutch theologian named Cornelius Jansen, who died in 1638. It was based at the Port-Royal-des-Champs Abbey, and was based on variations of the doctrines of original sin and predestination which were strongly opposed by the Jesuits. Followers of the Jansenists included the philosopher Blaise Pascal and playwright Jean Racine. Cardinal Richelieu had the leader of the Jansenists in Paris put in prison in 1638, and the Jesuits persuaded Pope Innocent X to condemn Jansenism as a heresy in 1653, but the doctrines spread and Jansenism was broadly tolerated by most Parisians, and contributed to undermining the unquestioned authority of the church which followed in the 18th century.[39]

Henry IV had declared a policy of tolerance toward the Protestants of France in the Edict of Nantes in 1598. On August 1, 1606, at the request of his chancellor, Sully, Henry IV granted the Protestants of Paris permission to build a church, as long as it was far from the center of the city. The new church was constructed at Charenton, six kilometers from the Bastille. In 1680, there were an estimated eight thousand five hundred Protestants in the city, or about two percent of the population. Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, leading to an important exodus of Protestants from the city, and forcing those who remained to practice their faith in secret.[40]

The Jewish population of Paris in the 17th century was extremely small, following centuries of persecution and expulsion; there were only about a dozen Jewish families in the city, coming originally from Italy, Central Europe, Spain or Portugal.[41]

Daily life

Public transportation

At the beginning of the 17th century, the nobles and wealthy Parisians traveled by carriage, horse, or in a chair inside an elegant box carried by servants. In 1660 there were three hundred carriages in the city.

Less fortunate travelers had to go on foot. Paris could be crossed on foot in less than thirty minutes. However, it could be a very unpleasant walk; the narrow streets were crowded with carts, carriages, wagons, horses, cattle and people; there were no sidewalks, and the paving stones were covered with a foul-smelling soup of mud, garbage and horse and other animal droppings. Shoes and fine clothing were quickly ruined.

In about 1612 a new form of public transport appeared, called the fiacre, a coach and driver which could be hired for short journeys. The business was started by an entrepreneur from Amiens named Sauvage on the rue Saint-Martin. It took its name from the enseigne or hanging sign on the building, with an image of Saint Fiacre. By 1623 there were several different companies offering the service. In 1657 a decree of the Parlement of Paris gave the exclusive rights to operate coaches for hire to an ecuyer of the King, Pierre Hugon, the sieur of Givry. In 1666, the Parlement fixed the fare at twenty sous for the first hour and fifteen sous for each additional hour; three livres and ten sols for a half day, and four livres and ten sols if the passenger desired to go into the countryside outside Paris, which required a second horse. In 1669 fiacres were required to have large numbers painted in yellow on the sides and rear of the coach.

In January 1662 the mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal, the inventor of one of the first calculating machines, proposed an even more original and rational means of transport; buying seats in carriages which traveled on a schedule on regular routes from one part of the city to another. He prepared a plan and the enterprise was funded by three of his friends, and began service in March 1662. Each carriage carried eight passengers, and a seat in one cost five sols. The doors of the carriages had the emblem of the city of Paris, and the coachmen wore the city colors, red and blue. The coaches followed five different itineraries, including from rue Saint-Antoine to the Luxembourg by the Pont Neuf, from the Luxembourg to rue Montmartre, and a circular line, called "The Tour de Paris." Pascal's company was a great success at the beginning, but over the years it was not able to make money; after the death of Pascal, it went out of business in 1677.[42]

The fiacre remained the main means of public transport until well into the 19th century, when it was gradually replaced by the omnibus, the horse-drawn tramway, and the eventually by the motorized fiacre, or taxicab.[43]

Street lights

At the beginning of the century, the streets of Paris were dark at night, lit only here and there with candles or oil lanterns. In 1662 the Abbé Laudati received royal letters of patent to establish a service providing torch-carriers and lantern-carriers for those who wanted to voyage through the streets at night. Lantern-bearers were located at posts eight hundred steps apart on the main streets, and customers paid five sols for each portion of a torch used, or for fifteen minutes of lantern-light. The company of torch and lantern bearers was in business until 1789.

In 1667, the royal government decided to go further, and to require the placement of lanterns in each quarter, and on every street and place, at the expense of the owners of the buildings on that street. In the first year, three thousand oil lanterns were put in place. The system was described by English traveler, Martin Lister, in 1698: "The streets are lit all winter and even during the full moon! The lanterns are suspended from in the middle of the street at a height of twenty feet and at a distance of twenty steps between each lantern." The lamps were enclosed in a glass cage two feet high, with a metal plaque on top. The cords were attached to iron bars fixed to the walls, so they could be lowered and refilled with oil. The King issued a commemorative medal to celebrate the event, with the motto Urbis securitas et nitor ("for the security and illumination of the city").[44]

Water

In the 17th century the drinking water of Paris came mostly from Seine, despite pollution of the river from the nearby tanneries and butcher shops. In the 18th century, taking drinking water from the river in the center of the city was finally banned. Some water also came from outside the city, from springs and reservoirs in Belleville, the Pré Saint-Gervais and La Vilette, carried in aqueducts built by the monks to the monasteries on the right bank. These also provided water to the palaces of the Louvre and the Tuileries, which together consumed about half the water supply of Paris.[45]

In 1607 Henry IV decided to build a large pump on the Seine next to the Louvre to increase the water supply for the palaces. The pump was located on the second arch of the Pont Neuf, in a high building decorated with a bas-relief of Jesus and the Samaritan at the wells of Jacob, which gave the pump the popular name of Samaritaine. The pump was finished in October 1608. The water was lifted by a wheel with eight buckets. it was supposed to lift 480,000 liters of water a day, but, because of numerous breakdowns, it only provided 20,000 liters a day, used by the neighboring palaces and gardens.

In 1670 the city contracted with the engineer in charge of the Samaritaine to build a second pump on the pont Notre-Dame, then, in the same year on the same bridge, a third pump. The two new pumps went into service in 1673. A series of wheels lifted the water up to the top of a tall square tower, where it was transferred to pipes and flowed by gravity to the palaces. The new pumps were able to provide two million liters a day.[46]

Marie de' Medici needed abundant water for her new palace and gardens on the left bank, which had few sources of water. Recalling that the ancient Romans had built an aqueduct from Rungis to their baths on the left bank, Sully, the minister of public works, sent engineers to find the route of the old aqueduct. A new aqueduct thirteen kilometers long was constructed 1613 and 1623, ending near the present-day Observatory, bringing 240,000 liters of water a day, enough for the dowager Queen's gardens and fountains. It enabled her to construct one of the best-known fountains in Paris today, the Medici Fountain, a reminder of her childhood in the Pitti Palace in Florence, in the gardens of the Luxembourg Palace.

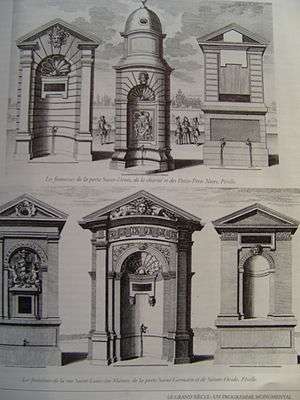

For those outside the palaces and monasteries, and the homes of nobles who had their own wells, the water came from the fountains of Paris. The first public fountain had been built in 1183 by King Philip Augustus at Les Halles, the central market, and a second, the Fontaine des Innocents was built in the 13th century. By the beginning of the 17th century there were a dozen fountains functioning within the center of the city. Between 1624 and 1628 Louis XIII built thirteen new fountains, providing water and decoration on the Parvis of the Cathedral of Notre Dame, on the Place de Greve, Place Maubert, Saint Severin, Place Royale, rue de Buci, porte Saint Michel, and other central points.[47]

The water was transported from the fountains to the residences of the Parisians by domestic servants or by water bearers, who, for a charge, carried it in two covered wooden buckets attached to a strap over his shoulders and to a frame. There were frequent disputes between water-bearers and domestic servants all trying to get water from the fountains. Frequently the water-bearers skipped the lines at the fountains and simply took the water from the Seine.[48]

Food and drink

Bread, meat and wine were the bases of the Parisian diet in the 17th century. As much of sixty percent of the income of working-class Parisians was spent on bread alone.[49] The taste of Parisian bread changed beginning in 1600 with the introduction of yeast, and, thanks to the introduction of milk into the bread, it became softer.[49] Poor harvests and speculation on the price of grain caused bread shortages and created hunger and riots, particularly in the winter of 1693-1694.[50]

Parisians consumed the meat of 50,000 beef cattle in 1634, increasing to 60,000 at the end of the century, along with 350,000 sheep and 40,000 pigs. The animals were taken live to the courtyards of the butcher shops in the neighborhoods, where they were slaughtered and the meat prepared. The best cuts of meat went to the nobility and upper classes, while working class Parisians consumed sausages, tripe and less expensive cuts, and made bouillon, or meat broth. A large quantity of fish was also consumed, particularly on Fridays and Catholic holidays.[51]

Wine was the third essential for the Parisians; not surprisingly, when the price of bread and meat increased, and living became more difficult, the consumption of wine also increased. Wine arrived by boat in large kegs at the ports near the Hotel de Ville from Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, and the Loire Valley. Less expensive wines came by wagon from vineyards on Montmartre and the surrounding Île-de-France. The tax on wine was a major source of income for the royal government; the wine was taxed as soon as it arrived at the port; the tax rose from three livres for a muid or barrel of wine in 1638 to 15 livres for wine arriving by land in 1680 and 18 livres for wine arriving by water.[52]

Cabarets

The cabaret was the ancestor of the restaurant, which did not appear until the 18th century. Unlike a tavern, which served wine by the pot without a meal, a cabaret only served wine accompanied by a meal, served on a tablecloth. Customers might sing if they had drunk enough wine, but in this era cabarets did not have formal programs of entertainment. They were popular meeting-places for Parisian artists and writers; La Fontaine, Moliere and Racine frequented the Mouton Blanc on rue du Vieux-Colombier, and later the Croix de Lorraine on the modern rue de Bourg-Tibourg.[53]

Coffee and the first cafés

Coffee was introduced to Paris from Constantinople in 1643; a merchant from the Levant sold cups of cahove in the covered passage between the rue Saint-Jacques and the Petit-Pont; and it was served as a novelty by Mazarin and in some noble houses, but it did not become fashionable until 1669 with the arrival of Soliman Aga Mustapha Aga, the ambassador of the Turkish sultan, Mahomet IV. In 1672 a coffee house was opened by an Armenian named Pascal at the Foire-Saint-Germain, serving coffee for two sous and six deniers for a cup. it was not a commercial success, and Pascal departed for London. A new café was opened by a Persian named Gregoire, who opened a coffee house near the theater of the Comédie-Française on rue Mazarin. When the theater moved to rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain in 1689, he moved the café with them. The café did not become a great success until it was taken over by a Sicilian, Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, who had first worked for Pascal in 1672. He bought the café and began serving coffee, tea, chocolate, liqueurs, ice creams and confitures. The new Cafe Procope became fashionable and successful, and was soon copied by other cafés in the city.[54]

Processions, carrousels and fireworks

The life of Parisians in the 17th century was usually hard and short, and perhaps for this reason the calendar was filled with holidays and celebrations. Religious processions were not as numerous as they had been in the Middle Ages, but they were colorful and impressive. The most important was in honor of the patron saint of the city, Saint Geneviève, from the church on the left bank containing her tomb to the Cathedral of Notre-Dame. The procession was led by the archbishop of Paris and the Abbé of the monastery of Sainte-Geneviève, in their full regalia and barefoot, preceded by one hundred and fifty monks and nuns. Behind them came the relics of the saint, carried by twenty men, also barefoot and dressed in white, carrying a jeweled chasse, followed by the members of the Parlement of Paris in their ceremonial scarlet robes, and the leaders of the leading guilds of craftsmen and artisans. There were processions for many different saints and holidays, which sometimes led to confrontations between the monks of different orders. According to Madame de Sevigné, in 1635 a procession of Benedictine monks refused to give way to a procession of Rogations, leading to a fight in the street in which two monks were struck with crucifixes and knocked unconscious.[55]

A ceremony from pre-Christian times, the Fire of Saint-Jean, was avidly celebrated in Paris on June 23, to mark the summer solstice. It was an enormous bonfire or series of fires, with burning twenty meters high, in front of the Hôtel de Ville. From the 14th century onwards, the fire was traditionally lit by the King himself. After the lighting, the crowd was offered wine and bread by the municipal government. While Henry IV and Louis XIII regularly took part, Louis XIV, discontented with the Parisians, only lit the fire once, and it was never lit by Louis XV or Louis XVI.[56]

For the nobility, the most important event at the beginning of the century was the carrousel, a series of exercises and games on horseback. These events were designed to replace the tournament, which had been banned after 1559 when King Henry II was killed in a jousting accident. In the new, less dangerous version, riders usually had to pass their lance through the interior of a ring, or strike mannequins with the heads of Medusa, Moors and Turks. The first carrousel in Paris was held in 1605 in the grand hall of the Hôtel Petit-Bourbon, an annex of the Louvre used for ceremonies. An elaborate carrousel took place 5–7 April 1612 at the Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges) to celebrate its completion. An even grander carrousel was held on June 5–6, 1662 to celebrate the birth of the Dauphin, the son of Louis XIV. It was held on the square separating the Louvre from the Tuileries Palace, which afterwards became known as the Place du Carrousel.[57]

The ceremonial entry of the King into Paris also became an occasion for festivities. The return of Louis XIV and Queen Marie-Thérèse to Paris after his coronation in 1660 was celebrated by a grand event on a fairground at the gates of the city, where large thrones were constructed for the new monarchs. After the ceremony the site became known as the Place du Trône, or place of the Throne, until it became the Place de la Nation in 1880.[58]

Another traditional Parisian form of celebration, the grand fireworks display, was born in the 17th century. Fireworks were first mentioned in Paris in 1581, and Henry IV had put on a small display at the Hôtel de Ville in 1598 after lighting the Fire of Saint Jean, but the first large show was given on April 12, 1612 following the Carrousel to mark the opening of the place Royale and the proposed marriage of Louis XIII with Anne of Austria. New innovations were introduced in 1615; allegorical figures of Jupiter on an eagle and Hercules, representing the King, were created with fireworks mounted on scaffolds next to the Seine and on a balcony of the Louvre. In 1618 the show was even more spectacular; rockets were launched into the sky which, according to one witness, the Abbot of Marolles, "burst into stars and serpents of fire." Thereafter fireworks, launched from the quays of the Seine, were a regular feature of the celebrations of holidays and special events. All they lacked were color; all the fireworks were white or pale gold, until the introduction from China of colored fireworks in the 18th century.[59]

Sports and games

The most popular sport for French nobles in the first part of the 17th century was the jeu de paume, a form of handball or tennis, which reached its peak of popularity under Henry IV, when there were more than 250 courts throughout the city. Louis XIV, however, preferred billiards, and the number of courts for jeu de paume dropped to 114. The owners of the courts found an original and effective strategy to survive; in 1667 they applied for and received permission to have billiards tables in their premises, and in 1727 they demanded and received the exclusive rights to operate public billiards parlors.[60]

Winters in Paris were much colder than today; Parisians enjoyed ice skating on the frozen Seine.

A match of jeu de paume

A match of jeu de paume Ice skaters on the Seine in 1608

Ice skaters on the Seine in 1608

Press

The press had a difficult birth in Paris; all publications were carefully watched and censored by the royal authorities. The first regular publication was the Mercure français, which first appeared in 1611, and then once a year until 1648.[61] It was followed in January 1631 by a more frequent publication with a long title, Nouvelles ordinaries de divers androids. In the same year the prominent Parisian doctor and philanthropist, Théophraste Renaudot, launched a weekly newspaper, La Gazette. Renaudot had good connections with Cardinal Richelieu, and his new paper was given royal patronage; La Gazette took over the earlier newspaper, and also became the first to have advertising. Later, in 1762, under the name Gazette de France, it became the official newspaper of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1665 a new weekly, Le Journal des savants appeared, followed in 1672 by Le Mercure Galant. which in 1724 became the Mercure de France.[61] The Mercure Galant was the first Paris periodical to report on fashion, and also became the first literary magazine; it published poetry and essays. The literature it published was not admired by everyone; the essayist Jean de La Bruyère described its literary quality as "immediately below nothing".[62]

Education

Academies

The young noblemen of Paris, since the end of the 16th century, attended special schools called academies, where they were taught a range of military skills: horseback riding, fencing, marksmanship, the art of fortification and organizing sieges, as well as the social skills that they needed to succeed at the court: dance, music, writing, arithmetic, drawing, and understanding heraldry and coats-of-arms. Each student had one or two valets, and the education cost between 700 and 1,000 ecus a year. By 1650, there were six academies in the city, mostly run by Italians. When the King departed Paris for Versailles, the large riding school of the Tuileries palace, the Manege, became part of one the academies, La Guériniére. In 1789, during the French Revolution, it became the home of the French National Assembly.[63]

University

Cardinal Richelieu and Cardinal Mazarin lavished funds on the buildings of the University of Paris; Richelieu built a magnificent new chapel for the college of Sorbonne, which he headed, while Cardinal Mazarin built the equally-magnificent College of the Six Nations, to house nobles from the most recently added provinces of France, but the educational system of the University, which was primarily a school of theology, was in continual crisis, trying to deal with multiple heresies and challenges to its authority from newly arrived religious orders. The Sorbonne, the leading college, was challenged by the new College of Clermont, run by the Jesuit order. The royal government sought to turn the University into a training school for magistrates and state officials, but found that the faculty was only trained in canon, or church law. A fire in 1670 destroyed much of the old Sorbonne, but fortunately spared the domed chapel. By the end of the 17th century one-third of the colleges of the University had closed, and the remaining thirty-nine colleges had barely enough students to survive.[64]

Primary education

In the 16th century, in the middle of the fierce struggle battle between Protestants and Catholics and between the hierarchy of the Paris church and the new religious orders in Paris, the authorities of the Paris church had tried to control the growing number of schools for Parisian children being organized in each parish, and particularly sought to limit the education of girls. However, throughout the 17th century, dozens of new schools were founded throughout the city for both boys and girls. By the 18th century a majority of children in Paris were in various kinds of schools; there were 316 private schools for paying students, regulated by the church, and another eighty free schools for the poor, including twenty-six schools for girls, plus additional schools founded by the new religious orders in Paris.[65]

Gardens and promenades

At the beginning of the 17th century there was one royal French Renaissance garden in Paris, the Jardin des Tuileries, created for Catherine de' Medici in 1564 to the west of her new Tuileries Palace. It was inspired by the gardens of her native Florence, particularly the Boboli Gardens, The garden was divided into squares of fruit trees and vegetable gardens divided by perpendicular alleys and by boxwood hedges and rows of cypress trees. Like Boboli, it featured a grotto, with faience "monsters."[66]

Under Henry IV the old garden was rebuilt, following a design of Claude Mollet, with the participation of Pierre Le Nôtre, the father of the famous garden architect. A long terrace was built on the north side, looking down at the garden, and a circular basin was constructed, along with an octagonal basin on the central axis.

Marie de' Medici, the widow of Henry IV, also was nostalgic for the gardens and promenades of Florence, particularly for the long tree-shaded alleys where the nobility could ride on foot, horseback and carriages, to see and be seen. In 1616 she had built the Cours-la-Reine a promenade 1.5 kilometers long, shaded by four rows of elm trees, along the Seine.

The Jardin du Luxembourg was created by Marie de' Medici around her new home, the Luxembourg Palace. between 1612 and 1630. She began by planting two thousand elm trees, and commissioned a Florentine gardener, Tommaso Francini, to build the terraces and parterres, and the circular basin the center. The Medici Fountain was probably also the work of Francini, though it is sometimes attributed to Salomon de Brosse, the architect of the palace.[67] The original fountain (see 1660 engraving at right) did not have statuary or a basin; these were added in the 19th century.

The Jardin des Plantes, originally called the Jardin royal des herbes médicinales, was opened in 1626, on land purchased from the neighboring Abbey of Saint Victor. It was under the supervision of Guy de la Brosse, the physician of King Louis XIII, and its original purpose was to provide medicines for the court. In 1640, it became the first Paris garden to open to the public.

In 1664 Louis XIV had the Tuileries garden redesigned by André Le Nôtre in the style of the classic French formal garden, with parterres bordered with low shrubs and bodies of water organized along a wide central axis. He added the Grand Carré around the circular basin at the east end of the garden, and the horseshoe-shaped ramp at the west end, leading to a view of the entire garden.

In 1667, Charles Perrault, the author of Sleeping Beauty and other famous fairy tales, proposed to Louis XIV that the garden be opened at times to public. His proposal was accepted, and the public (with the exception of soldiers in uniform, servants and beggars) were allowed on certain days to promenade in the park.[66]

Culture and the arts

Culture and the arts flourished in Paris in the 17th century, but, particularly under Louis XIV, the artists were dependent upon the patronage and taste of the King. As the philosopher Montesquieu wrote in his Lettres persanes in 1721: "The Prince impresses his character and his spirit on the Court; the Court on the City; and the City on the provinces."[62]

Literature