Paris Gun

| Paris Gun | |

|---|---|

|

The German Paris Gun, also known as William's Gun, was the largest artillery gun of World War I. In 1918 the Paris Gun was able to shell Paris from 120 kilometres (75 mi) away. | |

| Type | Super heavy field cannon |

| Place of origin | German Empire |

| Service history | |

| Used by | German Empire |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Fritz Rausenberger |

| Manufacturer | Krupp |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 256 tons |

| Length | 34 m (111 ft 7 in)[1]:84 |

|

| |

| Caliber | 211 mm, later rebored to 238 mm |

| Breech | horizontal sliding-block |

| Elevation | 55 degrees |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,640 m/s (5,400 ft/s) |

| Effective firing range | 130 km (81 mi) |

The Paris Gun (German: Paris-Geschütz / Pariser Kanone) was the name given to a type of German long-range siege gun, several of which were used to bombard Paris during World War I. They were in service from March to August 1918. When the guns were first employed, Parisians believed they had been bombed by a high-altitude Zeppelin, as the sound of neither an aeroplane nor a gun could be heard. They were the largest pieces of artillery used during the war by barrel length, and are considered to be superguns. The Paris Guns hold an important place in the history of astronautics, as their shells were the first human-made objects to reach the stratosphere.

Also called the "Kaiser Wilhelm Geschütz" ("Emperor William Gun"), they were often confused with Big Bertha, the German howitzer used against the Liège forts in 1914; indeed, the French called them by this name, as well.[Note 1] They were also confused with the smaller "Langer Max" (Long Max) cannon, from which they were derived; although the famous Krupp-family artillery makers produced all these guns, the resemblance ended there.

As military weapons, the Paris Guns were not a great success: the payload was small, the barrel required frequent replacement, and the guns' accuracy was only good enough for city-sized targets. The German objective was to build a psychological weapon to attack the morale of the Parisians, not to destroy the city itself.

Description

_-_Emplacement_d-une_Bertha_(pd).jpg)

The Paris Gun was a weapon like no other, but its capabilities are not known with full certainty. This is due to the weapon's apparent total destruction by the Germans in the face of the final Allied offensives. Figures stated for the weapon's size, range, and performance varied widely depending on the source—not even the number of shells fired is certain. With the discovery (in the 1980s) and publication (in the Bull and Murphy book) of a long note on the gun written shortly before his death in 1926 by Dr. Fritz Rausenberger, who was in charge of its development at Krupp, the details of its design and capabilities were considerably clarified.

The gun was capable of firing a 106-kilogram (234 lb)[1]:120 shell to a range of 130 kilometers (81 mi) and a maximum altitude of 42.3 kilometers (26.3 mi)[1]:120—the greatest height reached by a human-made projectile until the first successful V-2 flight test in October 1942. At the start of its 182-second trajectory,[1]:33 each shell from the Paris Gun reached a speed of 1,640 meters per second (5,400 ft/s).[1]:33

Seven barrels were constructed. They used worn-out 38 cm SK L/45 "Max" gun barrels that were fitted with an internal tube that reduced the caliber from 380 millimeters (15 in) to 210 millimeters (8 in). The tube was 21 meters (69 ft) long and projected 3.9 meters (13 ft) out of the end of the gun, so an extension was bolted to the old gun-muzzle to cover and reinforce the lining tube. A further, 12-meter–long smooth-bore extension was attached to the end of this, giving a total barrel length of 34 meters (112 ft).[1]:84 This smooth section was intended to improve accuracy and reduce the dispersion of the shells, as it reduced the slight yaw a shell might have immediately after leaving the gun barrel produced by the gun's rifling.[2] The barrel was braced to counteract barrel drop due to its length and weight, and vibrations while firing; it was mounted on a special rail-transportable carriage and fired from a prepared, concrete emplacement with a turntable. The original breech of the old 38 cm gun did not require modification or reinforcement.

Since it was based on a naval weapon, the gun was manned by a crew of 80 Imperial Navy sailors under the command of Vice-Admiral Rogge, chief of the Ordnance branch of the Admiralty.[1]:66 It was surrounded by several batteries of standard army artillery to create a "noise-screen" chorus around the big gun so that it could not be located by French and British spotters.

The projectile was the first human-made object to reach the stratosphere. Writer and journalist Adam Hochschild put it this way: "It took about three minutes for each giant shell to cover the distance to the city, climbing to an altitude of 25 miles (40 km) at the top of its trajectory. This was by far the highest point ever reached by a man-made object, so high that gunners, in calculating where the shells would land, had to take into account the rotation of the Earth. For the first time in warfare, deadly projectiles rained down on civilians from the stratosphere".[3] This reduced drag from air resistance, allowing the shell to achieve a range of over 130 kilometres (81 mi).

The unfinished V-3 cannon would have been able to fire somewhat larger projectiles to a longer range, and with a substantially higher rate of fire. The unfinished Iraqi super gun would also have been substantially bigger.

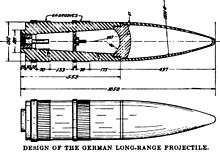

Projectiles

The Paris Gun shells weighed 106 kg (234 lb).[1]:120 The shells initially used had a diameter of 216 mm (8.5 in) and a length of 960 mm (38 in).[1]:120 The main body of the shell was composed of thick steel, containing 7 kg (15 lb) of TNT.[1]:120[Note 2] The small amount of explosive – around 6.6% of the weight of the shell – meant that the effect of its shellburst was small for the shell's size.[5] The thickness of the shell casing, to withstand the forces of firing, meant that shells would explode into a comparatively small number of large fragments, limiting their destructive effect.[5] A crater produced by a shell falling in the Tuileries Garden was described by an eyewitness as being 10 to 12 ft (3.0 to 3.7 m) across and 4 ft (1.2 m) deep.[6]

The shells were propelled at such a high velocity that each successive shot wore away a considerable amount of steel from the rifled bore. Each shell was sequentially numbered according to its increasing diameter, and had to be fired in numeric order, lest the projectile lodge in the bore, and the gun explode. Also, when the shell was rammed into the gun, the chamber was precisely measured to determine the difference in its length: a few inches off would cause a great variance in the velocity, and with it, the range. Then, with the variance determined, the additional quantity of propellant was calculated, and its measure taken from a special car and added to the regular charge. After 65 rounds had been fired, each of progressively larger caliber to allow for wear, the barrel was sent back to Krupp and rebored to a caliber of 238 mm (9.4 in) with a new set of shells.

The shell's explosive was contained in two compartments, separated by a wall. This strengthened the shell and supported the explosive charge under the acceleration of firing. One of the shell's two fuses was mounted in the wall, with the other in the base of the shell. The shell's nose was fitted with a streamlined, lightweight, ballistic cap – a highly unusual feature for the time – and the side had grooves that engaged with the rifling of the gun barrel, spinning the shell as it was fired so its flight was stable. Two copper driving bands provided a gas-tight seal against the gun barrel during firing.[5]

Use in World War I

The gun was fired from the forest of Coucy and the first shell landed at 7:18 a.m. on 21 March 1918 on the Quai de la Seine, the explosion being heard across the city. Shells continued to land at 15 minute intervals, with 21 counted on the first day.[7] The initial assumption was these were bombs dropped from an airplane or Zeppelin flying too high to be seen or heard.[Note 3] But within a few hours, sufficient casing fragments had been collected to show that the explosions were the result of shells, not bombs. By the end of the day, military authorities were aware the shells were being fired from behind German lines by a new long-range gun, although there was initially wild press speculation on the origin of the shells. This included the theory they were being fired by German agents close by Paris, or even within the city itself, so abandoned quarries close to the city were searched for a hidden gun.[7] However, the actual gun was found within days by the French air reconnaissance[8] aviator Didier Daurat.

The Paris gun emplacement was dug out of the north side of the wooded hill at Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique.[Note 4] The gun was mounted on heavy steel rails embedded in concrete, facing Paris.

The Paris gun was used to shell Paris at a range of 120 km (75 mi). The distance was so far that the Coriolis effect—the rotation of the Earth—was substantial enough to affect trajectory calculations. The gun was fired at an azimuth of 232 degrees (west-southwest) from Crépy-en-Laon, which was at a latitude of 49.5 degrees North.

A total of around 320 to 367 shells were fired, at a maximum rate of around 20 per day. The shells killed 250 people and wounded 620, and caused considerable damage to property. The worst incident was on 29 March 1918, when a single shell hit the roof of the St-Gervais-et-St-Protais Church, collapsing the entire roof on to the congregation then hearing the Good Friday service. A total of 91 people were killed and 68 were wounded. The incident inspired Romain Rolland to write his novel Pierre et Luce.

The gun was taken back to Germany in August 1918 as Allied advances threatened its security. No guns were ever captured by the Allies. It is believed that near the end of the war they were completely destroyed by the Germans. One spare mounting was captured by American troops in Bruyères-sur-Fère, near Château-Thierry, but the gun was never found; the construction plans seem to have been destroyed as well.[9]

After World War I

Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the Germans were required to turn over a complete Paris Gun to the Allies, but they never complied with this.[10]

In the 1930s, the German Army became interested in rockets for long range artillery as a replacement for the Paris Gun—which was specifically banned under the Versailles Treaty. This work would eventually lead to the V-2 rocket that was used in World War II.

Despite the ban, Krupp continued theoretical work on long-range guns. They started experimental work after the Nazi government began funding the project upon coming to power in 1933. This research led to the 21 cm K 12 (E), a refinement of the Paris Gun design.[11] Although it was broadly similar in size and range to its predecessor, Krupp's engineers had significantly reduced the problem of barrel wear. They also improved mobility over the fixed Paris Gun by making the K12 a railway gun.

The first K12 was delivered to the German Army in 1939 and a second in 1940. During World War 2, they were deployed in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France; they were used to shell Kent in Southern England between late 1940 and early 1941. One gun was captured by Allied forces in the Netherlands in 1945.[12]

In popular culture

A parody of the Paris Gun appears in the Charlie Chaplin movie The Great Dictator. Firing at the Cathedral of Notre Dame the "Tomanians" (the fictional country that represented Germany) succeed in blowing up a small outhouse.

In a mission in the game Blazing Angels 2: Secret Missions of WWII the player is required to disable or destroy a Paris Gun to progress in the mission.

Scrooge McDuck used a cannon called "Bertha" to defend his Money Bin against the Beagle Boys in DuckTales. Shown onscreen in the episode Catch as Cash Can: Part 1, the cannon was clearly of the same design as the Paris Gun.

The Paris Gun was referenced in S1E5 of the television series Time After Time, in the episode entitled "Picture Fades." When H. G. Wells is researching a particular date in WW1, their online research comes across a reference to the Paris Gun.

See also

- Krupp K5, a 283mm, World War II German Gun with a 64-kilometre (40 mi) range.

- V-3 cannon, World War II German Gun intended to bombard London from France.

Notes

- ↑ For an instance of war-time naming of this gun as "Big Bertha", see "Paris again Shelled by Long-Range Gun" (PDF). The New York Times. August 6, 1918. p. 3. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ↑ This overall weight of Paris Gun shells is not atypical for artillery of this calibre. As a comparison, World War 1-era, British BL 8-inch howitzer fired a 91 kg (201 lb) high-explosive shell. The 210mm shell fired by the World War 2-era 21 cm Kanone 39 weighed 135 kg (298 lb) and contained 18.8 kg (41 lb) of explosives (13.9% by weight).

- ↑ This was not an unreasonable assumption, as Zeppelins on night-time air-raids over the United Kingdom had previously used the tactic of cutting their engines when upwind of the target, then releasing their bombs as they silently drifted overhead.

- ↑ Position 49°31′40.43″N 3°18′17.57″E / 49.5278972°N 3.3048806°E

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bull, Gerald V.; Murphy, Charles H. (1988). Paris Kanonen: The Paris Guns (Wilhelmgeschutze) and Project HARP. Herford: E. S. Mittler. ISBN 3-8132-0304-2.

- ↑ Miller (1921) pg.737

- ↑ To End All Wars by Adam Hochschild c. 2011 Adam Hochschild(Houghton, Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company New York; 2011) pp.320 - 321

- ↑ Miller (1921) pg.742

- 1 2 3 Major J. Maitland-Addison (July–September 1918). "The Long Range Guns" (PDF). The Field Artillery Journal (3).

- ↑ Miller (1921) pg.83

- 1 2 Miller (1921) pg.723

- ↑ Miller (1921) pg.728

- ↑ Columbia Alumni News. Alumni Council of Columbia University (Vol. 10, No. 30). 1918. p. 937.

- ↑ Anne Cipriano Venzon (2 December 2013). The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 436. ISBN 978-1-135-68446-4.

- ↑ Ford (2000), p.116

- ↑ Ford (2000), p.117

- Bibliography

- Ford, Roger (2000). Germany's Secret Weapons in World War II. Zenith Imprint. ISBN 0760308470.

- Henry W. Miller, Railway Artillery: A Report on the Characteristics, Scope of Utility, etc. of Railway Artillery, United States Government Printing Office, 1921

- Henry W. Miller, The Paris Gun: The Bombardment of Paris by the German Long Range Guns and the Great German Offensive of 1918, Jonathan Cape, Harrison Smith, New York, 1930

- Bull, Gerald V.; Murphy, Charles H. (1988). Paris Kanonen: The Paris Guns (Wilhelmgeschutze) and Project HARP. Herford: E. S. Mittler. ISBN 3-8132-0304-2.

- Ian V. Hogg, The Guns 1914 -18, Ballantine Books, New York, 1971

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paris gun. |

- The Paris Gun in the First World War.com Encyclopedia

- Paris Gun at S. Berliner, III's ORDNANCE Superguns

- Une page sur le canon de Paris

- Map of impact sites