Pareto efficiency

Pareto efficiency or Pareto optimality is a state of allocation of resources from which it is impossible to reallocate so as to make any one individual or preference criterion better off without making at least one individual or preference criterion worse off. The concept is named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Italian engineer and economist, who used the concept in his studies of economic efficiency and income distribution. The concept has been applied in academic fields such as economics, engineering, and the life sciences.

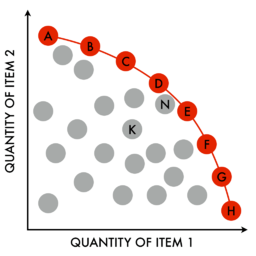

The Pareto frontier is the set of all Pareto efficient allocations, conventionally shown graphically.

A Pareto improvement is a change to a different allocation that makes at least one individual or preference criterion better off without making any other individual or preference criterion worse off, given a certain initial allocation of goods among a set of individuals. An allocation is defined as "Pareto efficient" or "Pareto optimal" when no further Pareto improvements can be made, in which case we are assumed to have reached Pareto optimality.

"Pareto efficiency" is considered as a minimal notion of efficiency that does not necessarily result in a socially desirable distribution of resources: it makes no statement about equality, or the overall well-being of a society.[1][2]

The notion of Pareto efficiency has been applied to the selection of alternatives in engineering and similar fields. Each option is first assessed, under multiple criteria, and then a subset of options is ostensibly identified with the property that no other option can categorically outperform any of its members.

Overview

"Pareto optimality" is a formally defined concept used to determine when an allocation is optimal. Simply put, an allocation is not Pareto optimal if there is an alternative allocation where improvements can be made to at least one participant's well-being without reducing any other participant's well-being. If there is a transfer that satisfies this condition, the reallocation is called a "Pareto improvement." When no further Pareto improvements are possible, the allocation is a "Pareto optimum."

The formal presentation of the concept in an economy is as follows: Consider an economy with agents and goods. Then an allocation , where , is Pareto optimal if there is no other feasible allocation such that, for utility function for each agent , for all with for some .[3] Here, in this simple economy, "feasibility" refers to an allocation where the total amount of each good that is allocated sums to no more than the total amount of the good in the economy. In a more complex economy with production, an allocation would consist both of consumption vectors and production vectors, and feasibility would require that the total amount of each consumed good is no greater than the initial endowment plus the amount produced.

In principle, a change from a generally inefficient economic allocation to an efficient one is not necessarily considered to be a Pareto improvement. Even when there are overall gains in the economy, if a single agent is disadvantaged by the reallocation, the allocation is not Pareto optimal. For instance, if a change in economic policy eliminates a monopoly and that market subsequently becomes competitive, the gain to others may be large. However, since the monopolist is disadvantaged, this is not a Pareto improvement. In theory, if the gains to the economy are larger than the loss to the monopolist, the monopolist could be compensated for its loss while still leaving a net gain for others in the economy, allowing for a Pareto improvement. Thus, in practice, to ensure that nobody is disadvantaged by a change aimed at achieving Pareto efficiency, compensation of one or more parties may be required. It is acknowledged, in the real world, that such compensations may have unintended consequences leading to incentive distortions over time, as agents supposedly anticipate such compensations and change their actions accordingly.[4]

Under the idealized conditions of the first welfare theorem, a system of free markets, also called a "competitive equilibrium," leads to a Pareto-efficient outcome. It was first demonstrated mathematically by economists Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu.

However, the result only holds under the restrictive assumptions necessary for the proof: markets exist for all possible goods, so there are no externalities; all markets are in full equilibrium; markets are perfectly competitive; transaction costs are negligible; and market participants have perfect information.

In the absence of perfect information or complete markets, outcomes will generally be Pareto inefficient, per the Greenwald-Stiglitz theorem.[5]

The second welfare theorem is essentially the reverse of the first welfare-theorem. It states that under similar, ideal assumptions, any Pareto optimum can be obtained by some competitive equilibrium, or free market system, although it may also require a lump-sum transfer of wealth.[3]

Weak Pareto efficiency

A "weak Pareto optimum" (WPO) is an allocation for which there are no possible alternative allocations whose realization would cause every individual to gain. Thus, an alternative allocation is considered to be a Pareto improvement if and only if the alternative allocation is strictly preferred by all individuals. When contrasted with weak Pareto efficiency, a standard Pareto optimum as described above may be referred to as a "strong Pareto optimum" (SPO).

Weak Pareto-optimality is "weaker" than strong Pareto-optimality in the sense that any SPO also qualifies as a WPO, but a WPO allocation is not necessarily an SPO.

A market doesn't require local nonsatiation to get to a weak Pareto-optimum.[6]

Constrained Pareto-efficiency

The condition of constrained Pareto-optimality is a weaker version of the standard condition of Pareto optimality employed in economics, which ostensibly accounts for the fact that a potential planner (e.g., the government) may not be able to improve upon a decentralized market outcome, even if that outcome is inefficient. This will occur if it is limited by the same informational or institutional constraints as are individual agents.[7]

The most commonly proffered example is of a setting where individuals have private information (for example, a labor market where the worker's own productivity is known to the worker but not to a potential employer, or a used-car market where the quality of a car is known to the seller but not to the buyer) which results in moral hazard or an adverse selection and a sub-optimal outcome. In such a case, a planner who wishes to improve the situation is deemed unlikely to have access to any information that the participants in the markets do not have. Hence, the planner cannot implement allocation rules which are based on the idiosyncratic characteristics of individuals; for example, "if a person is of type A, they pay price p1, but if of type B, they pay price p2" (see Lindahl prices). Essentially, only anonymous rules are allowed (of the sort "Everyone pays price p") or rules based on observable behavior; "if any person chooses x at price px then they get a subsidy of ten dollars, and nothing otherwise". If there exists no allowed rule that can successfully improve upon the market outcome, then that outcome is said to be "constrained Pareto-optimal."

Note that the concept of constrained Pareto optimality assumes benevolence on the part of the planner and hence it is distinct from the concept of government failure, which occurs when the policy making politicians fail to achieve an optimal outcome simply because they are not necessarily acting in the public's best interest.

Use in engineering and economics

The notion of Pareto efficiency has been used in engineering. Given a set of choices and a way of valuing them, the Pareto frontier or Pareto set or Pareto front is the set of choices that are Pareto efficient. By restricting attention to the set of choices that are Pareto-efficient, a designer can make tradeoffs within this set, rather than considering the full range of every parameter.

Formal representation

Pareto frontier

For a given system, the Pareto frontier or Pareto set is the set of parameterizations (allocations) that are all Pareto efficient. Finding Pareto frontiers is particularly useful in engineering. By yielding all of the potentially optimal solutions, a designer can make focused tradeoffs within this constrained set of parameters, rather than needing to consider the full ranges of parameters.

The Pareto frontier, P(Y), may be more formally described as follows. Consider a system with function , where X is a compact set of feasible decisions in the metric space , and Y is the feasible set of criterion vectors in , such that .

We assume that the preferred directions of criteria values are known. A point is preferred to (strictly dominates) another point , written as . The Pareto frontier is thus written as:

Relationship to the marginal rate of substitution

A significant aspect about the Pareto frontier in economics is that, at a Pareto-efficient allocation, the marginal rate of substitution is the same for all consumers. A formal statement can be derived by considering a system with m consumers and n goods, and a utility function of each consumer as where is the vector of goods, both for all i. The feasibility constraint is for . To find the Pareto optimal allocation, we maximize the Lagrangian:

where and are the vectors of multipliers. Taking the partial derivative of the Lagrangian with respect to each good for and and gives the following system of first-order conditions:

where denotes the partial derivative of with respect to . Now, fix any and . The above first-order condition imply that

Thus, in a Pareto-optimal allocation, the marginal rate of substitution must be the same for all consumers.

Computation

Algorithms for computing the Pareto frontier of a finite set of alternatives have been studied in computer science and power engineering.[8] They include:

- "The maximum vector problem" or the skyline query.[9][10]

- "The scalarization algorithm" or the method of weighted sums.

Criticisms

It would be incorrect to treat Pareto efficiency as equivalent to societal optimization, as the latter is a normative concept that is a matter of interpretation that typically would account for the consequence of degrees of inequality of distribution. An example would be a school district with low property tax revenue versus one with much higher revenue. Generally, more equal distribution occurs with the help of government redistribution.

Pareto efficiency does not require a totally equitable distribution of wealth. An economy in which a wealthy few hold the vast majority of resources can be Pareto efficient. This possibility is inherent in the definition of Pareto efficiency; often the status quo is Pareto efficient regardless of the degree to which wealth is equitably distributed. A simple example is the distribution of a pie among three people. The most equitable distribution would assign one third to each person. However the assignment of, say, a half section to each of two individuals and none to the third is also Pareto optimal despite not being equitable, because none of the recipients could be made better off without decreasing someone else's share; and there are many other such distribution examples. An example of a Pareto inefficient distribution of the pie would be allocation of a quarter of the pie to each of the three, with the remainder discarded. The origin (and utility value) of the pie is conceived as immaterial in these examples. In such cases, whereby a "windfall" is gained that none of the potential distributees actually produced (e.g., land, inherited wealth, a portion of the broadcast spectrum, or some other resource), the criterion of Pareto efficiency does not determine a unique optimal allocation. Wealth consolidation may exclude others from wealth accumulation because of bars to market entry, etc.

The liberal paradox elaborated by Amartya Sen shows that when people have preferences about what other people do, the goal of Pareto efficiency can come into conflict with the goal of individual liberty.

See also

- Admissible decision rule, analog in decision theory

- Arrow's impossibility theorem

- Bayesian efficiency

- Fundamental theorems of welfare economics

- Deadweight loss

- Economic efficiency

- Game theory

- Kaldor–Hicks efficiency

- Market failure, when a market result is not Pareto optimal

- Maximal element, concept in order theory

- Multi-objective optimization

- Nash equilibrium

- Robinson Crusoe economy

- Social Choice and Individual Values for the '(weak) Pareto principle'

- Social choice theory

- TOTREP

- Welfare economics

- Zero-sum game

References

- ↑ Barr, N. (2012). "3.2.2 The relevance of efficiency to different theories of society". Economics of the Welfare State (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-929781-8.

- ↑ Sen, A. (October 1993). "Markets and freedom: Achievements and limitations of the market mechanism in promoting individual freedoms" (PDF). Oxford Economic Papers. 45 (4): 519–541. JSTOR 2663703.

- 1 2 Mas-Colell, A.; Whinston, Michael D.; Green, Jerry R. (1995), "Chapter 16: Equilibrium and its Basic Welfare Properties", Microeconomic Theory, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510268-1

- ↑ See Ricardian equivalence

- ↑ Greenwald, B.; Stiglitz, J. E. (1986). "Externalities in economies with imperfect information and incomplete markets". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 101 (2): 229–64. JSTOR 1891114. doi:10.2307/1891114.

- ↑ Markey‐Towler, Brendan and John Foster. "Why economic theory has little to say about the causes and effects of inequality", School of Economics, University of Queensland, Australia, 21 Feb 2013, RePEc:qld:uq2004:476

- ↑ Magill, M., & Quinzii, M., Theory of Incomplete Markets, MIT Press, 2002, p. 104 .

- ↑ Tomoiagă, B.; Chindriş, M.; Sumper, A.; Sudria-Andreu, A.; Villafafila-Robles, R. Pareto Optimal Reconfiguration of Power Distribution Systems Using a Genetic Algorithm Based on NSGA-II. Energies 2013, 6, 1439–55.

- ↑ Kung, H. T.; Luccio, F.; Preparata, F.P. (1975). "On finding the maxima of a set of vectors.". Journal of the ACM. 22 (4): 469–76. doi:10.1145/321906.321910.

- ↑ Godfrey, P.; Shipley, R.; Gryz, J. (2006). "Algorithms and Analyses for Maximal Vector Computation". VLDB Journal. 16: 5–28. doi:10.1007/s00778-006-0029-7.

Further reading

- Fudenberg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1991). Game theory. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 18–23. ISBN 9780262061414. Book preview.

- Bendor, Jonathan; Mookherjee, Dilip (April 2008). "Communitarian versus Universalistic norms". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. Now Publishing Inc. 3 (1): 33–61. doi:10.1561/100.00007028.

- Kanbur, Ravi (January–June 2005). "Pareto's revenge" (pdf). Journal of Social and Economic Development. Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. 7 (1): 1–11.

- Ng, Yew-Kwang (2004). Welfare economics towards a more complete analysis. Basingstoke, Hampshire New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333971215.

- Rubinstein, Ariel; Osborne, Martin J. (1994), "Introduction", in Rubinstein, Ariel; Osborne, Martin J., A course in game theory, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 6–7, ISBN 9780262650403 Book preview.

- Mathur, Vijay K. (Spring 1991). "How well do we know Pareto optimality?". The Journal of Economic Education. Taylor and Francis via JSTOR. 22 (2): 172–178. doi:10.2307/1182422.

- Newbery, David M.G.; Stiglitz, Joseph E. (January 1984). "Pareto inferior trade". Review of Economic Studies. Oxford Journals. 51 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/2297701.