Consecutive fifths

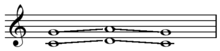

In music, consecutive fifths, or parallel fifths, are progressions in which the interval of a perfect fifth is followed by a different perfect fifth between the same two musical parts (or voices): for example, from C to D in one part along with G to A in a higher part. Octave displacement is irrelevant to this aspect of musical grammar; for example, parallel twelfths (i.e. an octave plus a fifth) are equivalent to parallel fifths.[nb 1]

Though used in, and evocative of, various kinds of popular, folk, and medieval music, parallel motion in perfect consonances (P1, P5, P8) is strictly forbidden in species counterpoint instruction (1725–present)[2] and during the common practice period, consecutive fifths were strongly discouraged. This was primarily due to the notion of voice leading in tonal music, in which, "one of the basic goals...is to maintain the relative independence of the individual parts."[3] The perfect intervals (the 4th, 5th and octave) sound 'pure'. This has the psychoacoustic effect momentarily of 'fusing' the separate voices and weakening their harmonic independence. Thus voices moving in parallel perfect intervals lose their harmonic autonomy momentarily. An analogy is to consider the flight of birds ‘welded’ together.

A common theory is that the presence of the 3rd harmonic of the harmonic series influenced the creation of the prohibition.

Development of the prohibition

Singing in consecutive fifths may have originated from the accidental singing of a chant a perfect fifth above (or a perfect fourth below) the proper pitch. Whatever its origin, singing in parallel fifths became commonplace in early organum and conductus styles. Around 1300, Johannes de Grocheo became the first theorist to prohibit the practice. However, parallel fifths were still common in 14th-century music. The early 15th-century composer Leonel Power likewise forbade the motion of "2 acordis perfite of one kynde, as 2 unisouns, 2 5ths, 2 8ths, 2 12ths, 2 15ths,"[4] and it is with the transition to Renaissance-style counterpoint that the use of parallel perfect consonances was consistently avoided in practice. The convention dates approximately from 1450.[3] Composers avoided writing consecutive fifths between two independent parts, such as tenor and bass lines.

Consecutive fifths were usually considered forbidden, even if disguised (e.g., in a "horn fifth") or broken up by an intervening note (e.g., the third/mediant in a triad). The interval may form part of a chord of any number of notes, and may be set well apart from the rest of the harmony, or finely interwoven in its midst. But the interval was always to be quit by any movement that did not land on another fifth.

The prohibition concerning fifths did not just apply to perfect fifths. Some theorists objected also to the progression from a perfect fifth to a diminished fifth in parallel motion; for example the progression from C and G to B and F (B and F forming a diminished fifth).

"The reason for avoiding parallel 5ths and 8ves has to do with the nature of counterpoint. The P8 and P5 are the most stable of intervals, and to link two voices through parallel motion at such intervals interferes with their independence much more than would parallel motion at 3rds or 6ths."[3] "Since the octave really represents a repetition of the same tone in a different register, if two or more octaves occur in succession, the result is a reduction in the number of voices; for example, in a two-voice setting, one of the voices would temporarily disappear, and along with it the rationale of the intended two-voice setting. The octave acts merely as a doubling; if, in a particular instance, it is not intended to act as such, this must be sufficiently emphasized by what precedes and follows it. But even the succession of two octaves brings the sense of doubling into the foreground. Of course, this must not be confused with an intentional doubling used to strengthen sonority, for which, however, strict counterpoint offers no motivation."[5] Similarly, "Parallel 8ves...reduce the number of voices...since the voice that [momentarily] doubles at the 8ve...is not an independent voice but merely a duplication. Parallel 8ves...may also confuse the functions of the voices...If the upper voice succession...is merely a duplication of the bass, then the actual soprano must be...the alto voice. This interpretation of course makes no sense, for it turns the texture inside out."[6] "Parallel 5ths are avoided because the 5th, formed by scale degrees 1 and 5, is the primary harmonic interval, the interval that divides the scale and thus defines the key. The direct succession of two 5ths raises doubt concerning the key."[6]

The identification and avoidance of perfect fifths in the instruction of counterpoint and harmony help to distinguish the more formal idiom of classical music from popular and folk musics, in which consecutive fifths commonly appear in the form of double tonics and shifts of level. The prohibition of consecutive fifths in European classical music originates not only in the requirement for contrary motion in counterpoint but in a gradual and eventually self-conscious attempt to distance classical music from folk traditions. As Sir Donald Tovey explains in his discussion of Joseph Haydn's Symphony no. 88, "The trio is one of Haydn's finest pieces of rustic dance music, with hurdy-gurdy drones which shift in disregard of the rule forbidding consecutive fifths. The disregard is justified by the fact that the essential objection to consecutive fifths is that they produce the effect of shifting hurdy-gurdy drones."[7] A more contemporary example would be guitar power chords.

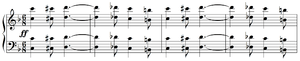

In the course of the 19th century consecutive fifths became more common, arising out of new textures and new conceptions of propriety in voice leading generally. They even became a stylistic feature in the work of some composers, notably Chopin; and with the early 20th century and the breakdown of common-practice norms the prohibition became less and less relevant.[8]

Related progressions

Unequal fifths

Unequal fifths, motion between perfect and diminished fifths is often avoided, with some avoiding only motion one way (diminished to perfect fifth or perfect to diminished fifth) or only if the bass is involved.[3] Notice that unequal fifths resemble similar rather than parallel motion, since the perfect fifth is seven semitones and the diminished fifth is six semitones.

Parallel octaves and fourths

Consecutive fifths are avoided in part because they cause a loss of individuality between parts. This lack of individuality is even more pronounced when parts move in parallel octaves or in unison. These are therefore also generally forbidden among independently moving parts.[nb 2]

Parallel fourths (consecutive perfect fourths) are allowed, even though a P4 is the inversion and thus the complement of a P5.[1] The literature deals with them less systematically however, and theorists have often restricted their use. Theorists commonly disallow consecutive perfect fourths involving the lowest part, especially between the lowest part and the highest part. Since the beginning of the common practice period, it has been theorized that all dissonances should be properly resolved to a perfect consonance (there are few exceptions). Therefore, parallel fourths above the bass are generally dismissed in voice leading as a series of consecutive unresolved dissonances. However parallel fourths in upper voices (especially as part of a parallel "6-3" sonorities) are common, and formed the basis of fifteenth-century fauxbourdon style. As an example of this type of allowed parallel perfect fourth in common practice music, see the final movement of Mozart's A minor Piano sonata whose theme in mm. 37-40 consists of parallel fourths in the right hand part (but not above the bass).

Hidden consecutives

So-called hidden consecutives, also called direct or covered octaves or fifths,[10][nb 3] occur when two independent parts approach a single perfect fifth or octave by similar motion instead of oblique or contrary motion. A single fifth or octave approached this way is sometimes called an exposed fifth or exposed octave. Conventional style dictates that such a progression be avoided; but it is sometimes permitted under certain conditions, such as the following: the interval does not involve either the highest or the lowest part, the interval does not occur between both of those extreme parts, the interval is approached in one part by a semitone step, or the interval is approached in the higher part by step. The details differ considerably from period to period, and even among composers writing in the same period.

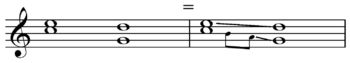

An important acceptable case of hidden fifths in the common practice period are horn fifths. Horn fifths arise from the limitation of valveless brass instruments to the notes of the harmonic series (hence their name). In all but their extreme high registers, these brass instruments are limited to the notes of the major triad. The typical two-instrument configuration would have the high instrument playing a scalar melody against a lower instrument confined to the notes of the tonic chord. Horn fifths occur when the upper voice is on the first three scale degrees.

Traditional horn fifths actually come in pairs. Begin with the upper instrument on the third scale degree and the lower instrument on the tonic. Then move the upper instrument to the second scale degree and the second instrument down to the fifth scale degree. Because the distance from 5 up to 2 is a perfect fifth, we have just created a hidden fifth by descending motion. The first instrument can then complete its descent to 1 as the lower instrument moves to 3. The second hidden fifth of the pair is obtained by making the upward maneuver a mirror image of the downward maneuver. These direct fifths are preferable to other less acceptable voice-leading alternatives including doubling the third scale degree at the octave, and limiting the low instrument to the use of only the first and fifth scale degrees. Although traditional horn fifths come in pairs and in passing, the acceptability of horn fifths has been generalized to any situation of hidden fifths where the top voice moves by step.

Special uses and exceptions in early music

Consecutive fifths are typically used to evoke the sound of music in medieval times or exotic places. The use of parallel fifths (or fourths) to refer to the sound of traditional Chinese or other kinds of Eastern music was once commonplace in film scores and songs. Since these passages are an obvious oversimplification and parody of the styles that they seek to evoke, this use of parallel fifths declined during the last half of the 20th century.

In the medieval period, large church organs and positive organs would often be permanently arranged for each single key to speak in a consecutive fifth. It is believed this practice dates to Roman times. A positive organ having this configuration has been reconstructed recently by Van der Putten and is housed in Groningen, and is used in an attempt to rediscover performance practice of the time.

In Iceland, the traditional song style known as tvísöngur, "twin-singing", goes back to the Middle Ages and is still taught in schools today. In this style, a melody is sung against itself, typically in parallel fifths.

Georgian music frequently uses parallel fifths, and sometimes parallel major ninths above the fifths. This means that there are two sets of parallel fifths, one directly on top of the other. This is especially prominent in the sacred music of the Guria region, in which the pieces are sung a cappella by men. It is believed that this harmonic style dates from pre-Christian times.

Consecutive fifths (as well as fourths and octaves) are commonly used to mimic the sound of Gregorian plainsong. This practice is well-founded in early European musical traditions. Plainsong was originally sung in unison, not in fifths, but by the ninth century there is evidence that singing in parallel intervals (fifths, octaves, and fourths) commonly ornamented the performance of chant. This is documented in the anonymous ninth-century theory treatises known as Musica enchiriadis and its commentary Scolica enchiriadis. These treatises use Daseian music notation, based on four-note patterns called tetrachords, which easily notates parallel fifths. This notation predates Guido of Arezzo's solmization, which divides the scale into six-note patterns called hexachords, and the modern octave-based staff notation into which Guido's gamut evolved.

Mozart fifths

In Brahms' essay "Octaven und Quinten," he identifies many cases of apparent consecutive fifths in the works of Mozart. Most of the examples he provides involve accompaniment figuration in small note values that moves in parallel fifths with a slower moving bass. The background voice-leading of such progressions is oblique motion, with the consecutive fifths resulting from the ornamentation of the sustaining voice with a chromatic lower neighbor. Such "Mozart Fifths" occur in bar 254-255 of the Act I finale of Così fan Tutte, in bar 80 of the Act II sextet from Don Giovanni, and in bar 189 of the overture to Zauberflöte.

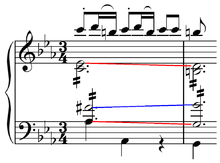

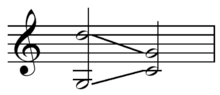

Another use of the term "Mozart fifths" results from the non-standard resolution of the German augmented sixth chord that Mozart used occasionally, such as in the retransition of the finale of the Jupiter Symphony (bars 222-223) and in the example at the right from Symphony No. 39 (Mozart). Mozart (and all common-practice composers) almost always resolves German augmented sixth chords to cadential six-four chords to avoid these fifths. The Jupiter example is unique in that Mozart spells the fifth enharmonically (A-flat and d-sharp) as a result of the progression arising from a B-major harmony (presented as a dominant of e-minor). Arnold Schoenberg humorously refers to these as acceptable only because Mozart wrote them.[12] Other theorists have tried to make the case that this resolution of the augmented sixth chord is more frequently acceptable. "The parallel fifths [in the German sixth] arising from the natural progression to the dominant are always considered acceptable, except when occurring between soprano and bass. They are most often seen between tenor and bass. The third degree is, however, frequently tied over as a suspension, or repeated as an appoggiatura, before continuing down to the second degree".[13] However, seeing as the vast majority of German augmented sixth chords in common-practice works resolve to cadential six-four chords to avoid parallel fifths, it can be concluded that common-practice composers deemed these fifths undesirable in most situations.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thus, the word "parallel" is not truly synonymous with "consecutive" here, as a fifth followed by another fifth approached with contrary motion would still count as consecutive fifths. The term parallel fifths may therefore be misleading, because some consecutive fifths occur with contrary motion: from a true uncompounded fifth to a twelfth, for example. If parts move by oblique motion (for example, one part moving from a C to a higher C, and another part repeating a G higher than both of those Cs), the intervals are not considered to differ in the relevant way, so parallel fifths do not occur.

- ↑ The restriction to independently moving parts is important. It has always been standard to double a part in unison or at the octave, even at several different octaves simultaneously, for the duration of a phrase or beyond. For contrapuntal and harmonic analysis this does not add new parts at all. By convention, common practice sometimes allows more transient parallel octaves, or even fifths, with certain melodic embellishments such as anticipations.(Piston 1987, pp. 306–312.)

- ↑ The traditional terms for these progressions are as vague and variable as the traditional rules that govern them.

Sources

- 1 2 Kostka & Payne (1995). Tonal Harmony, p.85. Third Edition. ISBN 0-07-300056-6.

- 1 2 3 Benward & Saker (2003). Music in Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.155. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Kostka & Payne (1995), p.84.

- ↑ Meech, Sanford B. (1935). "Three Musical Treatises in English from a Fifteenth-Century Manuscript". Speculum. 10 (3): 242. JSTOR 2848378.

- ↑ Jonas, Oswald (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker, p.110. (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers). Trans. John Rothgeb. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- 1 2 Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept & Practice, p.50. Third edition. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.

- ↑ Tovey, Donald Francis. Essays in musical analysis, vol. 1, p. 142. Quoted in van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music, p. 210. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-316121-4.

- ↑ Piston, Walter (1987). Harmony, 5th edition revised DeVoto, Mark, pp. 309–312, 477–480. ISBN 978-0-393-95480-7.

- ↑ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.133. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ↑ Piston (1987), p. 32.

- ↑ Ellis, Mark R. (2010). A Chord in Time: The Evolution of the Augmented Sixth Sonority from Monteverdi to Mahler, p.5. ISBN 9780754663850.

- ↑ Schoenberg, Arnold, Theory of Harmony, third edition 1922, trans. Roy Carter, University of California Press, 1978, p. 246.

- ↑ Piston (1987), p. 422.

Further reading

- Jeppesen, Knud. Counterpoint: the polyphonic vocal style of the sixteenth century, English translation 1939, reprint by Dover, NY, 1992. ISBN 0-486-27036-X.

- Meech, Sanford. "Three Musical Treatises in English from a Fifteenth-Century Manuscript", Speculum X.3, July 1935.

- Mast, Paul (1980). "Brahms's Study, Octaven u. Quinten u. A., with Schenker's Commentary Translated", Music Forum V. Cited in Jonas (1982), p. 112n84.

External links

- Hopkins, Pandora and Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson: Iceland, Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 8 June 2006), Grove Music - Access by subscription only

.png)