''p''-Cresol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-Methylphenol | |

| Other names

4-Hydroxytoluene, p-Hydroxytoluene, p-Methylphenol, 4-Cresol, p-Cresylic acid, 1-Hydroxy-4-methylbenzene | |

| Identifiers | |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.090 |

| KEGG | |

| RTECS number | GO6475000 |

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C7H8O | |

| Molar mass | 108.13 |

| Appearance | colorless prismatic crystals |

| Density | 1.0347 g/ml |

| Melting point | 35.5 °C (95.9 °F; 308.6 K) |

| Boiling point | 201.8 °C (395.2 °F; 474.9 K) |

| 2.4 g/100 ml at 40 °C 5.3 g/100 ml at 100 °C | |

| Solubility in ethanol | fully miscible |

| Solubility in diethyl ether | fully miscible |

| Vapor pressure | 0.11 mmHg (25°C)[1] |

| -72.1·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Refractive index (nD) |

1.5395 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May be fatal if swallowed, inhaled, or absorbed through skin. |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R34 R24 R25 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | S36 S37 S39 S45 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Flash point | 86.1 °C (187.0 °F; 359.2 K) |

| Explosive limits | 1.1%-?[1] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LD50 (median dose) |

207 mg/kg (oral, rat, 1969) 1800 mg/kg (oral, rat, 1944) 344 mg/kg (oral, mouse)[2] |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

| PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 5 ppm (22 mg/m3) [skin][1] |

| REL (Recommended) |

TWA 2.3 ppm (10 mg/m3)[1] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) |

250 ppm[1] |

| Related compounds | |

| Related phenols |

o-cresol, m-cresol, phenol |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

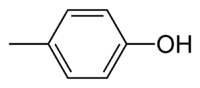

para-Cresol, also 4-methylphenol, is an organic compound with the formula CH3C6H4(OH). It is a colourless solid that is widely used intermediate in the production of other chemicals. It is a derivative of phenol and is an isomer of o-cresol and m-cresol.[3]

Production

Together with many other compounds, p-cresol is traditionally extracted from coal tar, the volatilized materials obtained in the roasting of coal to produce coke. This residue contains a few percent by weight of phenol and cresols. p-Cresol is currently prepared industrially mainly by a two step route beginning with the sulfonation of toluene:

- CH3C6H5 + H2SO4 → CH3C6H4SO3H + H2O

Base hydrolysis of the sulfonate salt gives the sodium salt of the cresol:

- CH3C6H4SO3Na + 2 NaOH → CH3C6H4OH + Na2SO3 + H2O

Other methods for the production of p-cresol include chlorination of toluene followed by hydrolysis. In the cymene-cresol process, phenol is alkylated with propylene to give p-cymene, which can be oxidatively dealkylated.[3]

Applications

p-Cresol is mainly consumed in the production of antioxidants, e.g., butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The monoalkylated derivatives undergo coupling to give an extensive family of diphenol antioxidants. These antioxidants are valued because they are relatively low in toxicity and nonstaining.[3]

Natural occurrences

In humans

p-Cresol is produced by bacterial fermentation of protein in the human large intestine. It is excreted in the feces and urine,[4] and is a component of human sweat that is attractive to female mosquitoes.[5][6]

p-Cresol is a constituent of tobacco smoke.[7]

In other species

p-Cresol is a major component in pig odor.[8]

Temporal glands secretion examination showed the presence of phenol and p-cresol during musth in male elephants.[9][10]

p-Cresol is one of the very few compounds to attract the orchid bee Euglossa cyanura and has been used to capture and study the species.[11]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0156". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ "Cresol (o, m, p isomers)". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 Fiege, Helmut (2000). "Cresols and Xylenols". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. ISBN 3-527-30673-0. doi:10.1002/14356007.a08_025.

- ↑ Hamer, H. M.; De Preter, V.; Windey, K.; Verbeke, K. (2011). "Functional analysis of colonic bacterial metabolism: relevant to health?". AJP: Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 302 (1): G1–G9. ISSN 0193-1857. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2011.

- ↑ Hallem, Elissa A.; Nicole Fox, A.; Zwiebel, Laurence J.; Carlson, John R. (2004). "Olfaction: Mosquito receptor for human-sweat odorant". Nature. 427 (6971): 212–3. Bibcode:2004Natur.427..212H. PMID 14724626. doi:10.1038/427212a.

- ↑ Linley, John R. (1989). "Laboratory tests of the effects of p-cresol and 4-methylcyclohexanol on oviposition by three species of Toxorhynchites mosquitoes". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 3 (4): 347–52. PMID 2577519. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2915.1989.tb00241.x.

- ↑ Talhout, Reinskje; Schulz, Thomas; Florek, Ewa; Van Benthem, Jan; Wester, Piet; Opperhuizen, Antoon (2011). "Hazardous Compounds in Tobacco Smoke". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (12): 613–628. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 3084482

. PMID 21556207. doi:10.3390/ijerph8020613.

. PMID 21556207. doi:10.3390/ijerph8020613. - ↑ http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=why-study-pig-odor%5B%5D

- ↑ Rasmussen, L.E.L; Perrin, Thomas E (1999). "Physiological Correlates of Musth: Lipid Metabolites and Chemical Composition of Exudates". Physiology & Behavior. 67 (4): 539–49. PMID 10549891. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(99)00114-6.

- ↑ Ananth, Deepa. "Musth in elephants" (PDF). Zoos' Print Journal. 15 (5): 259–62. doi:10.11609/jott.zpj.14.4.259-62.

- ↑ Williams, Norris H.; Whitten, W. Mark (June 1983). "Orchid Floral Fragrances and Male Euglossine Bees: Methods and Advances in the Last Sesquidecade". Biological Bulletin. 164 (3): 355–95. JSTOR 1541248. doi:10.2307/1541248.