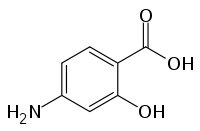

4-Aminosalicylic acid

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Paser |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | by mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 50–60% |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.557 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H7NO3 |

| Molar mass | 153.135 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 150.5 °C (302.9 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

4-Aminosalicylic acid, also known as para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) is an antibiotic primarily used to treat tuberculosis.[1] Specifically it is used to treat active drug resistant tuberculosis together with other antituberculosis medications. It has also been used as a second line agent to sulfasalazine in people with inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. It is typically taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include nausea, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Other side effects may include liver inflammation and allergic reactions. It is not recommended in people with end stage kidney disease. While there does not appear to be harm with use during pregnancy it has not been well studied in this population. 4-Aminosalicylic acid is believed to work by blocking the ability of bacteria to make folic acid.[2]

4-Aminosalicylic acid was first made in 1902 and came into medical use in 1943.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[4] As of 2005 a course of treatment for tuberculosis costs about 2,700 USD.[5]

Medical uses

The main use for 4-aminosalicylic acid is for the treatment of tuberculosis infections.

Tuberculosis

Aminosalicylic acid was introduced to clinical use in 1944. It was the second antibiotic found to be effective in the treatment of tuberculosis, after streptomycin. PAS formed part of the standard treatment for tuberculosis prior to the introduction of rifampicin and pyrazinamide.[6]

Its potency is less than that of the current five first-line drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin) for treating tuberculosis and its cost is higher, but it is still useful in the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.[7] PAS is always used in combination with other anti-TB drugs.

The dose when treating tuberculosis is 150 mg/kg/day divided into two to four daily doses; the usual adult dose is therefore approximately 2 to 4 grams four times a day. It is sold in the US as "Paser" by Jacobus Pharmaceutical, which comes in the form of 4 g packets of delayed-release granules. The drug should be taken with acid food or drink (orange, apple or tomato juice).[8] PAS was once available in a combination formula with isoniazid called Pasinah[9] or Pycamisan 33.[10]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended granting a marketing authorization for PAS in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in adults and children when other treatments cannot "be devised for reasons of resistance or tolerability."[11]

Inflammatory bowel disease

PAS has also been used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease),[12] but has been superseded by other drugs such as sulfasalazine and mesalazine.

Others

PAS has been investigated for the use in manganese chelation therapy, and a 17-year follow-up study shows that it might be superior to other chelation protocols such as EDTA.[13]

Side effects

Gastrointestinal side-effects (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) are common; the delayed-release formulation is meant to help overcome this problem.[14] It is also a cause of drug-induced hepatitis. Patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency should avoid taking aminosalicylic acid as it causes haemolysis.[15] Thyroid goitre is also a side-effect because aminosalicylic acid inhibits the synthesis of thyroid hormones.[16]

Drug interactions include elevated phenytoin levels. When taken with rifampicin, the levels of rifampicin in the blood fall by about half.[17]

The U.S. FDA assigned PAS to pregnancy category C, indicating that it is not known whether it will harm an unborn baby.

Pharmacology

With heat, aminosalicylic acid is decarboxylated to produce CO2 and 3-aminophenol.[18]

Mode of action

PAS has been shown to be a pro-drug and it is incorporated into the folate pathway by dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) and dihydrofolate synthase (DHFS) to generate a hydroxyl dihydrofolate antimetabolite, which in turn inhibits dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzymatic activity.[19]

History

PAS was first synthesized by Seidel and Bittner in 1902.[3] It was rediscovered by the Swedish chemist Jörgen Lehmann upon the report that the tuberculosis bacterium avidly metabolized salicylic acid.[20] Lehmann first tried PAS as an oral TB therapy late in 1944. The first patient made a dramatic recovery.[21] The drug proved better than streptomycin, which had nerve toxicity and to which TB could easily develop resistance. In the 1948, researchers at Britain's Medical Research Council demonstrated that combined treatment with streptomycin and PAS was superior to either drug alone, and established the principle of combination therapy for tuberculosis.[7][3]

Other names

Like many commercially significant compounds, PAS has many names including para-aminosalicylic acid, p-aminosalicylic acid, 4-ASA, and simply P.

References

- ↑ WHO Model Formulary 2008 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2009. p. 140. ISBN 9789241547659. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Aminosalicylic Acid". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 Donald, Peter R; Diacon, Andreas H. "Para-aminosalicylic acid: the return of an old friend". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 15 (9): 1091–1099. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00263-7.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (19th List)" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Garrett W.; Yamey, Gavin; Wamala, Sarah. "Chapter 12". The Handbook of Global Health Policy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118509609.

- ↑ Mitchison DA (2000). "Role of individual drugs in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis Role of individual drugs in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis". Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 4 (9): 796–806. PMID 10985648.

- 1 2 Fox, W.; Ellard, G. A.; Mitchison, D. A. (1999). "Studies on the treatment of tuberculosis undertaken by the British Medical Research Council tuberculosis units, 1946-1986, with relevant subsequent publications". The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 3 (10 Suppl 2): S231–S279. PMID 10529902.

- ↑ "Paser". RxList. Archived from the original on September 13, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Smith NP, Ryan TJ, Sanderson KV, Sarkany I (1976). "Lichen scrofulosorum: A report of four cases". Br J Dermatol. 94 (3): 319–325. PMID 1252363. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb04391.x.

- ↑ Black JM; Sutherland, IB (1961). "Two incidents of tuberculous infection by milk from attested herds". Br Med J. 1 (5241): 1732–1735. PMC 1954350

. PMID 20789163. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5241.1732.

. PMID 20789163. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5241.1732. - ↑ Drug Discovery & Development. EMA Recommends Two New Tuberculosis Treatments. November 22, 2013.

- ↑ Daniel F, Seksik P, Cacheux W, Jian R, Marteau P (2004). "Tolerance of 4-aminosalicylic acid enemas in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and 5-aminosalicylic-induced acute pancreatitis". Inflamm Bowel Dis. 10 (3): 258–260. PMID 15290921. doi:10.1097/00054725-200405000-00013.

- ↑ Jiang, Y. M.; Mo, X. A.; Du, F. Q.; Fu, X.; Zhu, X. Y.; Gao, H. Y.; Xie, J. L.; Liao, F. L.; Pira, E.; Zheng, W. (2006). "Effective Treatment of Manganese-Induced Occupational Parkinsonism with p-Aminosalicylic Acid: A Case of 17-Year Follow-Up Study". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 48 (6): 644–649. PMID 16766929. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000204114.01893.3e.

- ↑ Das, K. M.; Eastwood, M. A.; McManus, J. P. A.; Sircus, W. (1973). "Adverse Reactions during Salicylazosulfapyridine Therapy and the Relation with Drug Metabolism and Acetylator Phenotype". New England Journal of Medicine. 289 (10): 491–495. PMID 4146729. doi:10.1056/NEJM197309062891001.

- ↑ Szeinberg, A.; Sheba, C.; Hirshorn, N.; Bodonyi, E. (1957). "Studies on erthrocytes in cases with past history of favism and drug-induced acute hemolytic anemia". Blood. 12 (7): 603–613. PMID 13436516.

- ↑ MacGregor, A. G.; Somner, A. R. (1954). "The anti-thyroid action of para-aminosalicylic acid". Lancet. 267 (6845): 931–936. PMID 13213079. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(54)92552-0.

- ↑ Boman G (1974). "Serum concentration and half-life of rifampicin after simultaneous oral administration of aminosalicylic acid or isoniazid". European journal of clinical pharmacology. 7 (3): 217–25. PMID 4854257. doi:10.1007/BF00560384.

- ↑ Vetuschi, C.; Ragno, G.; Mazzeo, P. (1988). "Determination of p-aminosalicylic acid and m-aminophenol by derivative UV-spectrophotometry". Journal of pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis. 6 (4): 383–391. PMID 16867404. doi:10.1016/0731-7085(88)80003-7.

- ↑ Zheng, J; Rubin, EJ; Bifani, P; Mathys, V; Lim, V; Au, M; Jang, J; Nam, J; Dick, T; Walker, JR; Pethe, K; Camacho, LR. "para-Aminosalicylic acid is a prodrug targeting dihydrofolate reductase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis". J Biol Chem. 288 (32): 23447–56. PMID 23779105. doi:10.1074/jbc.m113.475798.

- ↑ LEHMANN, JORGEN (1949-12-01). "The Treatment of Tuberculosis in Sweden with Para-Aminosalicylic Acid (PAS): A Review". Diseases of the Chest. 16 (6): 684–703. doi:10.1378/chest.16.6.684.

- ↑ Lehmann, J. (1946). "Para-aminosalicylic acid in the treatment of tuberculosis". Lancet. 1 (6384): 15–16. PMID 21008766. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(46)91185-3.