Pappus's hexagon theorem

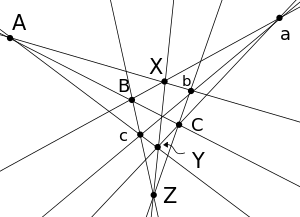

In mathematics, Pappus's hexagon theorem (attributed to Pappus of Alexandria) states that given one set of collinear points A, B, C, and another set of collinear points a, b, c, then the intersection points X, Y, Z of line pairs Ab and aB, Ac and aC, Bc and bC are collinear, lying on the Pappus line. These three points are the points of intersection of the "opposite" sides of the hexagon AbCaBc. It holds in a projective plane over any field, but fails for projective planes over any noncommutative division ring.[1] Projective planes in which the "theorem" is valid are called pappian planes.

The dual of this incidence theorem states that given one set of concurrent lines A, B, C, and another set of concurrent lines a, b, c, then the lines x, y, z defined by pairs of points resulting from pairs of intersections A∩b and a ∩ B, A ∩ c and a ∩ C, B ∩ c and b ∩ C are concurrent. (Concurrent means that the lines pass through one point.)

Pappus's theorem is a special case of Pascal's theorem for a conic—the limiting case when the conic degenerates into 2 straight lines. Pascal's theorem is in turn a special case of the Cayley–Bacharach theorem.

The Pappus configuration is the configuration of 9 lines and 9 points that occurs in Pappus's theorem, with each line meeting 3 of the points and each point meeting 3 lines. In general, the Pappus line does not pass through the point of intersection of ABC and abc.[2] This configuration is self dual. Since, in particular, the lines Bc, bC, XY have the properties of the lines x, y, z of the dual theorem, and collinearity of X, Y, Z is equivalent to concurrence of Bc, bC, XY, the dual theorem is therefore just the same as the theorem itself. The Levi graph of the Pappus configuration is the Pappus graph, a bipartite distance-regular graph with 18 vertices and 27 edges.

Proof

Choose projective coordinates with

- C = (1, 0, 0), c = (0, 1, 0), X = (0, 0, 1), A = (1, 1, 1).

On the lines AC, Ac, AX, given by x2 = x3, x1 =x3, x2 = x1, take the points B, Y, b to be

- B = (p, 1, 1), Y = (1, q, 1), b = (1, 1, r)

for some p, q, r. The three lines XB, CY, cb are x1 = x2p, x2 = x3q, x3 = x1r, so they pass through the same point a if and only if rqp = 1. The condition for the three lines Cb, cB and XY x2 = x1q, x1 = x3p, x3 = x2r to pass through the same point Z is rpq = 1. So this last set of three lines is concurrent if all the other eight sets are because multiplication is commutative, so pq = qp. Equivalently, X, Y, Z are collinear.

The proof above also shows that for Pappus's theorem to hold for a projective space over a division ring it is both sufficient and necessary that the division ring is a (commutative) field. German mathematician Gerhard Hessenberg proved that Pappus's theorem implies Desargues's theorem.[3][4] In general, Pappus's theorem holds for some projective plane if and only if it is a projective plane over a commutative field. The projective planes in which Pappus's theorem does not hold are Desarguesian projective planes over noncommutative division rings, and non-Desarguesian planes.

The proof is invalid if C, c, X happen to be collinear. In that case an alternative proof can be provided, for example, using a different projective reference.

Origins

In its earliest known form, Pappus's Theorem is Propositions 138, 139, 141, and 143 of Book VII of Pappus's Collection.[5] These are Lemmas XII, XIII, XV, and XVII in the part of Book VII consisting of lemmas to the first of the three books of Euclid's Porisms.

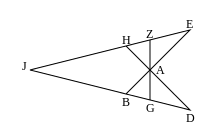

The lemmas are proved in terms of what today is known as the cross ratio of four collinear points. Three earlier lemmas are used. The first of these, Lemma III, has the diagram below (which uses Pappus's lettering, with G for Γ, D for Δ, J for Θ, and L for Λ).

Here three concurrent straight lines, AB, AG, and AD, are crossed by two lines, JB and JE, which concur at J. Also KL is drawn parallel to AZ. Then

- KJ : JL :: (KJ : AG & AG : JL) :: (JD : GD & BG : JB).

These proportions might be written today as equations:[6]

- KJ/JL = (KJ/AG)(AG/JL) = (JD/GD)(BG/JB).

The last compound ratio (namely JD : GD & BG : JB) is what is known today as the cross ratio of the collinear points J, G, D, and B in that order; it is denoted today by (J, G; D, B). So we have shown that this is independent of the choice of the particular straight line JD that crosses the three straight lines that concur at A. In particular

- (J, G; D, B) = (J, Z; H, E).

It does not matter on which side of A the straight line JE falls. In particular, the situation may be as in the next diagram, which is the diagram for Lemma X.

Just as before, we have (J, G; D, B) = (J, Z; H, E). Pappus does not explicitly prove this; but Lemma X is a converse, namely that if these two cross ratios are the same, and the straight lines BE and DH cross at A, then the points G, A, and Z must be collinear.

What we showed originally can be written as (J, ∞; K, L) = (J, G; D, B), with ∞ taking the place of the (nonexistent) intersection of JK and AG. Pappus shows this, in effect, in Lemma XI, whose diagram, however, has different lettering:

What Pappus shows is DE.ZH : EZ.HD :: GB : BE, which we may write as

- (D, Z; E, H) = (∞, B; E, G).

The diagram for Lemma XII is:

The diagram for Lemma XIII is the same, but BA and DG, extended, meet at N. In any case, considering straight lines through G as cut by the three straight lines through A, (and accepting that equations of cross ratios remain valid after permutation of the entries,) we have by Lemma III or XI

- (G, J; E, H) = (G, D; ∞ Z).

Considering straight lines through D as cut by the three straight lines through B, we have

- (L, D; E, K) = (G, D; ∞ Z).

Thus (E, H; J, G) = (E, K; D, L), so by Lemma X, the points H, M, and K are collinear. That is, the points of intersection of the pairs of opposite sides of the hexagon ADEGBZ are collinear.

Lemmas XV and XVII are that, if the point M is determined as the intersection of HK and BG, then the points A, M, and D are collinear. That is, the points of intersection of the pairs of opposite sides of the hexagon BEKHZG are collinear.

Other statements of the theorem

In addition to the above characterizations of Pappus's theorem and its dual, the following are equivalent statements:

- If the six vertices of a hexagon lie alternately on two lines, then the three points of intersection of pairs of opposite sides are collinear.[7]

- Arranged in a matrix of nine points (as in the figure and description above) and thought of as evaluating a permanent, if the first two rows and the six "diagonal" triads are collinear, then the third row is collinear.

- That is, if ABC, abc, AbZ, BcX, CaY, XbC, YcA, ZaB are lines, then Pappus's theorem states that XYZ must be a line. Also, note that the same matrix formulation applies to the dual form of the theorem when (A,B,C) etc. are triples of concurrent lines.[8]

- Given three distinct points on each of two distinct lines, pair each point on one of the lines with one from the other line, then the joins of points not paired will meet in (opposite) pairs at points along a line.[9]

- If two triangles are perspective in at least two different ways, then they are perspective in three ways.[3]

- If AB, CD, and EF are concurrent and DE, FA, and BC are concurrent, then AD, BE, and CF are concurrent.[8]

Notes

- ↑ Coxeter, pp. 236–7

- ↑ However, this does occur when ABC and abc are in perspective, that is, Aa, Bb and Cc are concurrent.

- 1 2 Coxeter 1969, p. 238

- ↑ According to (Dembowski 1968, pg. 159, footnote 1), Hessenberg's original proof Hessenberg (1905) is not complete; he disregarded the possibility that some additional incidences could occur in the Desargues configuration. A complete proof is provided by Cronheim 1953.

- ↑ Heath (Vol. II, p. 421) cites these propositions. The latter two can be understood as converses of the former two. Kline (p. 128) cites only Proposition 139. The numbering of the propositions is as assigned by Hultsch.

- ↑ A reason for using the notation above is that, for the ancient Greeks, a ratio is not a number or a geometrical object. We may think of ratio today as an equivalence class of pairs of geometrical objects. Also, equality for the Greeks is what we might today call congruence. In particular, distinct line segments may be equal. Ratios are not equal in this sense; but they may be the same.

- ↑ Coxeter, p. 231

- 1 2 Coxeter, p. 233

- ↑ Whicher, chapter 14

References

- Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald (1969), Introduction to Geometry (2nd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-50458-0, MR 123930

- Cronheim, A. (1953), "A proof of Hessenberg's theorem", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society, 4: 219–221, doi:10.2307/2031794

- Dembowski, Peter (1968), Finite Geometries, Berlin: Springer Verlag

- Heath, Thomas (1981) [1921], A History of Greek Mathematics, New York: Dover

- Hessenberg, Gerhard (1905), "Beweis des Desarguesschen Satzes aus dem Pascalschen", Mathematische Annalen, Berlin / Heidelberg: Springer, 61 (2): 161–172, ISSN 1432-1807, doi:10.1007/BF01457558

- Hultsch, Fridericus (1877), Pappi Alexandrini Collectionis Quae Supersunt, Berlin

- Kline, Morris (1972), Mathematical Thought From Ancient to Modern Times, New York: Oxford University Press

- Whicher, Olive (1971), Projective Geometry, Rudolph Steiner Press, ISBN 0-85440-245-4