Indochinese tiger

| Indochinese tiger | |

|---|---|

_832-714-(118).jpg) | |

| At the Tierpark Berlin | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. tigris |

| Subspecies: | P. t. corbetti |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris corbetti Mazák, 1968 | |

| |

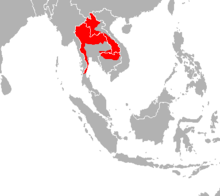

| Distribution of the Indochinese tiger | |

The Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) (Thai: เสือ โคร่ง อิน โด จีน, S̄eụ̄x khor̀ng xin do cīn) (Vietnamese: Hổ Đông Dương) was recognized as a tiger subspecies occurring in Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Viet Nam, Cambodia, and southwestern China. It has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2008, as the population seriously declined and approaches the threshold for Critically Endangered. As per 2011, the population was thought to comprise 342 individuals.[1] The largest population unit survives in Thailand estimated at 189 to 252 individuals.[2] There are 85 individuals in Myanmar, and only 20 Indochinese tigers remain in Viet Nam.[1] It is considered extinct in Cambodia.[3]

The tiger population in Peninsular Malaysia is known as the Malayan tiger.[4] In 2017, tiger populations of mainland Asia were subsumed to P. t. tigris.[5]

Taxonomy

The Indochinese tiger was proposed as a distinct subspecies in 1968 based on skin coloration, marking pattern and skull dimensions. It was named P. t. corbetti in honor of Jim Corbett.[6] Until 2017, it was widely recognised as a subspecies, and is now subsumed to P. t. tigris.[5]

Characteristics

The Indochinese tiger's skull is smaller than of the Bengal tiger; the ground coloration is darker with more rather short and narrow single stripes.[6][7] In body size, it is smaller than Bengal and Siberian tigers. Males range in size from 2.55 to 2.85 m (8.4 to 9.4 ft) and in weight from 150 to 195 kg (331 to 430 lb). Females range in size from 2.3 to 2.55 m (7.5 to 8.4 ft) and in weight from 100 to 130 kg (220 to 290 lb).[8]

Distribution and habitat

The Indochinese tiger' range includes Myanmar, Thailand and Laos.[1] In Myanmar, presence of tigers was confirmed in the Hukawng Valley, Tamanthi Wildlife Reserve, and in two small areas in the Tanintharyi Region. The Tenasserim Hills is an important area, but forests are harvested there.[9] More than half of the total population survives in the Western Forest Complex in Thailand, especially in the area of the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. This habitat consists of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests.[10]

It has not been recorded in Viet Nam since 1997. Available data suggest that there are no more breeding tigers left in Cambodia, Viet Nam and China.[11] In China, it occurred historically in the Yunnan province and Mêdog County in the country's southwestern part, where tigers probably do not survive any more today.[12] One was killed and eaten by five villagers in 2009.[13]

Results of a phylogeographic study using 134 samples from tigers across the global range suggest that the historical northwestern distribution limit of the Indochinese tiger is the region in the Chittagong Hills and Brahmaputra River basin, bordering the historical range of the Bengal tiger.[14][15] Tigers were recorded in Pakke Tiger Reserve and Namdapha National Park in Arunachal Pradesh.[16]

Indochinese tigers live in forests, grasslands, mountains and hills. They prefer mostly forested habitats such as tropical rainforests, evergreen forests, deciduous forests, tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests. Forests provide camouflage, and hunting grounds that fit their lifestyle and dietary needs.[17]

| Country | Minimum | Maximum | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | Extinct | 30 | Fair |

| Lao PDR | 9 | 23 | Fair |

| Myanmar | 85 | 85 | Fair |

| Thailand | 200 | 200 | Fair |

| Vietnam | 10 | 19 | Poor |

| Total | 314 | 357 |

The above figures were collected during a meeting of the International Tiger Forum ("Tiger Summit"), held in St. Petersburg, Russia, on 21–24 November 2010. Participants included representatives of 13 tiger range countries.[18]

Ecology and behavior

The Indochinese tiger is a solitary animal. Due to its elusive behavior it is difficult to be observed and studied in the wild, so there is little knowledge about their behaviour.[17]

Indochinese tigers prey mainly on medium- and large-sized wild ungulates. Sambar deer, wild pigs, serow, and large bovids such as banteng and juvenile gaur comprise the majority of Indochinese tiger’s diet. However, in most of Southeast Asia large animal populations have been seriously depleted because of illegal hunting, resulting in the so-called “empty forest syndrome” – i.e. a forest that looks intact, but where most wildlife has been eliminated.[19][20] Some prey species, such as the kouprey and Schomburgk's Deer, are extinct, and Eld's Deer, hog deer, and wild water buffalo are present only in a few relict populations. In such habitats, tigers are forced to subsist on smaller prey, such as muntjac deer, porcupines, macaques and hog badgers. Small prey by itself is barely sufficient to meet the energy requirements of a large carnivore such as the tiger, and is insufficient for tiger reproduction. This factor, in combination with direct tiger poaching for traditional Chinese medicine, is the main contributor in the collapse of the Indochinese tiger throughout its range.[21]

Reproduction

_841-723-(118).jpg)

Indochinese tigers mate throughout the year, but most frequently during November through early April. After a gestation period of 3.5 months, roughly 103 days, a female Indochinese tiger is capable of giving birth to seven cubs. However, on average a female will only give birth to three. Indochinese tiger cubs are born with their eyes and ears closed until they begin to open and function just a few days after birth. During the first year of life there is a 35% mortality rate, and 73% of those occurrences of infant mortality are the entire litter. Infant mortality in Indochinese tigers is often the result of fire, flood, and infanticide. As early as 18 months for some but as late as 28 months for others, Indochinese tiger cubs will break away from their mothers and begin hunting and living on their own. Females of the subspecies reach sexual maturity at 3.5 years of age while it takes males up to 5 years to reach sexual maturity.[17][22]

Their lifespan can range from 15 to 26 years of age depending on factors like living conditions and whether they are wild or in captivity. Due to their dwindling numbers, Indochinese tigers are known to inbreed, mating with available immediate family members. Inbreeding within this subspecies has led to weakened genes, lowered sperm count, infertility and in some cases defects such as cleft palates, squints, crossed-eyes, and swayback.[17][22]

Threats

_843-725-(118).jpg)

The primary threat to Indochinese tigers is mankind. Humans hunt Indochinese tigers to make use of their body parts for adornments and various Eastern traditional medicines. Indochinese tigers are also facing habitat loss. Humans are encroaching upon their natural habitats, developing, fragmenting, and destroying the land. In Taiwan, a pair of tiger eyes, which are believed to fight epilepsy and malaria, can sell for as much as $170. In Seoul, powdered tiger humerus bone, which is believed to treat ulcers, rheumatism, and typhoid, sells for $1,450 per pound. In China, the trade and use of tiger parts was banned in 1993, but that has not stopped poachers who can earn as much as $50,000 from the sale of a single tiger’s parts on the black market. With a growing affluence in countries where tiger parts are so greatly valued, demand is high.[23]

Located in the Kachin State of Myanmar, the Hukaung Valley is the world's largest tiger reserve and is home to Myanmar's remaining Indochinese tiger population. Since 2006, the Yuzana Corporation's wealthy owner Htay Myint alongside local authorities has expropriated more than 200,000 acres of land from more than 600 households in the valley. Much of the trees have been cut down and the land has been transformed into plantations. Some of the land taken by the Yazana Corporation had been deemed tiger transit corridors. These are areas of land that were supposed to be left untouched by development in order to allow the region’s Indochinese tigers to travel between protected pockets of reservation land.[24] The Burmese Civil War has been an ongoing conflict within the country of Myanmar since 1948. Because of renewed rebel uprising in 2011 from the Kachin Independence Army who occupy a portion of the Hukaung Valley, foreign poaching threats have been unable to safely enter the region. Not only are foreigners restricted from entering the region but reservation staff as well. Among indigenous people, particularly the impoverished, the Indochinese tiger is a valuable resource. Because of the danger of civil conflict, the reservation staff have had a difficult time protecting the tigers from the native population. In early January 2013, rumors of a ceasefire between the government and rebel forces began to circulate. The country’s leaders believed that a resolution could have been reached as early as October 2013. Having been unable to establish themselves as a protective force in the region, there is concern that foreign poachers will begin moving back into the soon to be peaceful region before the reservation staff.[25]

Despite being illegal, the trade of tiger parts on the black market provides many poachers with substantial income. While it is an illegal and frowned upon profession, many poachers do what they do because they are impoverished and have limited options for obtaining a substantial and steady income otherwise.

Consequences

Throughout out all ecosystems they inhabit, tigers are a top predator. When a top predator is in decline or even totally removed from an ecosystem, there are serious consequences that trickle down through the food web and disrupt the proper functioning of an ecosystem. They control population growth and decline and increase species diversity.[26]

In captivity

Of all tiger subspecies, the Indochinese tiger is the least represented in captivity and not part of a coordinated breeding program. As of 2007, 14 individuals were recognized as Indochinese tigers based on genetic analysis of 105 captive tigers in 14 countries.[27]

National Geographic Society News Watch contributor Jordan Schaul wrote:

Prior to the designation of the Malay subspecies there were approximately 60 Indochinese tigers in Asian, European and North American zoos. Today there are less than a handful. Zoos are committed to conserving the genetic integrity of the subspecies that do exist in the wild.[28]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Lynam, A. J. & Nowell, K. (2011). "Panthera tigris ssp. corbetti". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-1. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- ↑ "Tiger population grows 50 per cent in Thai wildlife sanctuaries". TODAYonline. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ↑ "Tigers declared extinct in Cambodia". The Guardian. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ Kawanishi, K.; Lynam, T. (2008). "Panthera tigris subsp. jacksoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 Kitchener, A.C., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C., Eizirik, E., Gentry, A., Werdelin, L., Wilting, A. and Yamaguchi, N. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 76.

- 1 2 Mazák, V. (1968). Nouvelle sous-espèce de tigre provenant de l'Asie du sud-est. Mammalia 32 (1): 104.

- ↑ Mazák, V.; Groves, C. P. (2006). "A taxonomic revision of the tigers (Panthera tigris) of Southeast Asia". Mammalian Biology. 71: 268–287. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2006.02.007.

- ↑ Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152: 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004.

- ↑ Lynam, A.J., Saw Tun Khaing and Khin MaungZaw (2006). Developing a national tiger action plan for the Union of Myanmar. Environmental Management 37 (1): 30–39.

- ↑ Simcharoen, S., Pattanavibool, A., Karanth, K.U., Nichols, J.D. and Kumar, N.S. (2007). How many tigers Panthera tigris are there in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand? An estimate using photographic capture-recapture sampling. Oryx 41 (04): 447–453.

- ↑ Walston, J.; Robinson, J. G.; Bennett, E. L.; Breitenmoser, U.; da Fonseca, G. A. B.; et al. (2010). "Bringing the Tiger Back from the Brink—The Six Percent Solution". PLOS Biology. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000485.

- ↑ Kang, A., Xie, Y., Tang, J., Sanderson, E. W., Ginsburg, J. R. and Zhang, E. (2010). Historic distribution and recent loss of tigers in China. Integrative Zoology 5: 335–341.

- ↑ "The last known wild tiger in China killed and eaten by villagers". Daily Mail. 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ Luo, S.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Johnson, W. E.; van der Walt, J.; Martenson, J.; Yuhki, N.; Miquelle, D. G.; Uphyrkina, O.; Goodrich, J. M.; Quigley, H. B.; Tilson, R.; Brady, G.; Martelli, P.; Subramaniam, V.; McDougal, C.; Hean, S.; Huang, S.-Q.; Pan, W.; Karanth, U. K.; Sunquist, M.; Smith, J. L. D., O'Brien, S. J. (2004). "Phylogeography and genetic ancestry of tigers (Panthera tigris)". PLoS Biology. 2 (12): e442. PMC 534810

. PMID 15583716. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442.

. PMID 15583716. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020442. - ↑ Luo, S.J.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Applying molecular genetic tools to tiger conservation". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 351–362.

- ↑ Jhala, Y. V., Qureshi, Q., Sinha, P. R. (Eds.) (2011). Status of tigers, co-predators and prey in India, 2010. National Tiger Conservation Authority, Govt. of India, New Delhi, and Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun. TR 2011/003 pp-302

- 1 2 3 4 "The Indochinese Tiger". www.tigers.org.za. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- 1 2 GTRP (2011). Global Tiger Recovery Program 2010–2022. Global Tiger Initiative, Washington, DC.

- ↑ "Asia’s biodiversity vanishing into the marketplace".

- ↑ "Wildlife trade creating "empty forest syndrome" across the globe".

- ↑ Karanth, K. U., Stith, B. M. (1999). Prey depletion as a critical determinant of tiger population viability. Pages 100–113 in: Seidensticker, J. Christie, S., Jackson, P. (eds.) Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64835-1

- 1 2 "Indo-Chinese Tiger". Indian Tiger Welfare Society. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ "The Trade in Tiger Parts". Tigers in Crisis. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ Martov, Seamus. "World's Largest Tiger Reserve 'Bereft of Cats'". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Rook, D. "Civil war endangers Myanmar's ailing tigers". AFP. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ↑ Ripple, W. "Study: Loss of predators affects ecosystems". United Press International, Inc. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Luo, S. J., Johnson, W. E., Martenson, J., Antunes, A., Martelli, P., Uphyrkina, O., Traylor-Holzer, K., Smith, J. L. D. & O'Brien, S. J. (2008). Subspecies genetic assignments of worldwide captive tigers increase conservation value of captive populations. Current Biology 18 (8): 592–596.

- ↑ Schaul, J. (2010). "Managing Tiger Species Survival in American Zoos". National Geographic Society News Watch. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

External links

- Species portrait Panthera tigris and short portrait P. t. corbetti; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

- Description from Fort Worth Zoo

- Save The Tiger Fund : Indochinese Tiger

- WWF: Information on Tigers in the Greater Mekong region