Gargantua and Pantagruel

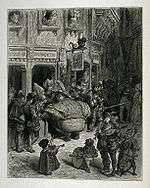

Illustration by Gustave Doré, 1873 | |

|

Pantagruel (c. 1532) Gargantua (1534) The Third Book of Pantagruel (1546) The Fourth Book of Pantagruel (1552) The Fifth Book of Pantagruel (c. 1564)' | |

| Author | François Rabelais ("Alcofribas Nasier") |

|---|---|

| Original title | La vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel |

| Translator | Thomas Urquhart, Peter Anthony Motteux |

| Illustrator | Gustave Doré (1854 edition) |

| Country | France |

| Language | Classical French |

| Genre | Satire |

| Published | c. 1532 – c. 1564 |

| Published in English | 1693–1694 |

| No. of books | 5 |

The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel (French: La vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel) is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais, which tells of the adventures of two giants, Gargantua (/ɡɑːrˈɡæntʃuːə/; French: [ɡaʁ.ɡɑ̃.ty.a]) and his son Pantagruel (/pænˈtæɡruːˌɛl, -əl, ˌpæntəˈɡruːəl/; French: [pɑ̃.ta.ɡʁy.ɛl]). The text is written in an amusing, extravagant, and satirical vein, and features much crudity, scatological humor, and violence (lists of explicit or vulgar insults fill several chapters).

The censors of the Collège de la Sorbonne stigmatized it as obscene,[1] and in a social climate of increasing religious oppression in a lead up to the French Wars of Religion, it was treated with suspicion, and contemporaries avoided mentioning it.[2] According to Rabelais, the philosophy of his giant Pantagruel, "Pantagruelism", is rooted in "a certain gaiety of mind pickled in the scorn of fortuitous things" (French: une certaine gaîté d'esprit confite dans le mépris des choses fortuites).

Rabelais had studied Ancient Greek and he applied it in inventing hundreds of new words in the text, some of which became part of the French language.[3] Wordplay and risqué humor abound in his writing.

Initial publication

Although different editions divide the work into a varying number of tomes, the original book is a single novel consisting of five volumes.

| Vol. | Short title | Full title | English title | Published |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pantagruel | Les horribles et épouvantables faits et prouesses du très renommé Pantagruel Roi des Dipsodes, fils du Grand Géant Gargantua | The Horrible and Terrifying Deeds and Words of the Very Renowned Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes, Son of the Great Giant Gargantua | c. 1532 |

| 2 | Gargantua | La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel | The Very Horrific Life of Great Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel | 1534 |

| 3 | The Third Book of Pantagruel | Le tiers livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel | The Third Book of the Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Good Pantagruel | 1546 |

| 4 | The Fourth Book of Pantagruel | Le quart livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel | The Fourth Book of the Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Good Pantagruel | 1552 |

| 5 | The Fifth Book of Pantagruel | Le cinquiesme et dernier livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel | The Fifth and Last Book of the Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Good Pantagruel | c. 1564 |

Plot summary

Pantagruel

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The full modern English title for the work commonly known as Pantagruel is The Horrible and Terrifying Deeds and Words of the Very Renowned Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes, Son of the Great Giant Gargantua and in French, Les horribles et épouvantables faits et prouesses du très renommé Pantagruel Roi des Dipsodes, fils du Grand Géant Gargantua. The original title of the work was Pantagruel roy des dipsodes restitué à son naturel avec ses faictz et prouesses espoventables.[4] Although most modern editions of Rabelais's work place Pantagruel as the second volume of a series, it was actually published first, around 1532 under the pen name "Alcofribas Nasier",[4] an anagram of François Rabelais.

Pantagruel was a sequel to an anonymous book entitled The Great Chronicles of the Great and Enormous Giant Gargantua (in French, Les Grandes Chroniques du Grand et Enorme Géant Gargantua). This early Gargantua text enjoyed great popularity, despite its rather poor construction. Rabelais's giants are not described as being of any fixed height, as in the first two books of Gulliver's Travels, but vary in size from chapter to chapter. For example, in one chapter Pantagruel is able to fit into a courtroom to argue a case, but in another the narrator resides inside Pantagruel's mouth for 6 months and discovers an entire nation living around his teeth.

At the beginning of this book, Gargantua's wife dies giving birth to Pantagruel, who grows to be as giant and scholarly as his father. Rabelais gives a catalog of his reading, mostly humorously-titled books, and judgements in nonsensical legal cases. "The lion's share of Pantagruel's seventh chapter consists of a concluding catalog attributed to the Abbey of Saint-Victor," states Bodemer in his essay, "Rabelais and the Abbey of Saint-Victor Revisited".[5]

He befriends hard-partying jokester Panurge. Together with a group of friends, they intoxicate an army of invading giants, burn their camp, and drown survivors in urine. Epistemon, decapitated in the fray, recovers when Panurge sews his head back to his body. He reports that souls in hell are poorly paid and work bad jobs, but that's the extent of their torments. Another battle is missed by the narrator, who is exploring the civilization in Pantagruel's mouth at the time.

Gargantua

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

After the success of Pantagruel, Rabelais revisited and revised his source material. He produced an improved narrative of the life and acts of Pantagruel's father in The Very Horrific Life of Great Gargantua, Father of Pantagruel (in French, La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, père de Pantagruel), commonly known as Gargantua. This volume begins with the miraculous birth of Gargantua after an 11-month pregnancy.

The labor is so difficult, his mother threatens to castrate his father, Lord Grandgousier. The giant Gargantua emerges at his mother's left ear, calling for ale, while 17,913 cows were required for the provision of his daily milk. His first garment featured a codpiece whose "exiture, outjecting or outstanding ... was of the length of a yard",[6] its contents providing so much delight that his three nurses squabble over claims to it.[7] After some indifferent education at home, he is sent to Paris where the crowds so annoy him that he drowns thousands of them in a flood of urine (the survivors laugh so much, the city is renamed "Par Ris").

He steals the bells of St. Anthony, but gives them back after a sophist makes ludicrously self-centered appeals for their return. While he studies diligently in Paris, the neighboring Lord Picrochole's bakers are insulted and attacked by Grandgousier's shepards. A massive retaliatory strike against Grandgousier's lands is finally halted at Seville by the merciless Friar John. Grandgousier sues for peace, but Picrochole arrogantly rebuffs him. Gargantua and Friar John rally the troops and (after Gargantua nearly swallows 6 pilgrims who accidentally fell in his salad) they win a great battle, drive Picrochole back to his city, then overthrow it.

As a reward, Friar John is given funds to establish the "anti-church" Abbey of Thélème, which has become one of the most notable parables in Western philosophy. It can be considered a point-by-point critique of the educational practices of the age, or a call for free schooling, or a defense of all sorts of notions on human nature.

The Third Book

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Rabelais then returned to the story of Pantagruel himself in the last three books. In The Third Book of Pantagruel (in French, Le tiers-livre de Pantagruel; the original title is Le tiers livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel[4]), the narrative style changes to a parody of the philosophical dialogue, where the earthy Panurge gets the last word. He sermonizes against moral restraint and in favor of indebtedness, yet accepts Pantagruel's offer to repay all of his creditors.

Now financially solvent for the first time, Panurge stops wearing his long codpiece and seeks advice about whom to marry. Various auguries (opening Virgil to a random page, inducing prophetic dream through half-hearted fasting) and councillors – the Sibyl of Panzoust, the mute Goatnose, the old poet Raminagrobis, Friar John, a group of learned doctors and lawyers, and a fool – all agree that if he marries, his wife will cheat on him, beat him, and rob him. But he egregiously reinterprets their prophecies in a more favorable light.

In a brief interlude, Pantagruel defends Judge Brindlegoose, who has pronounced sentence by rolling dice for 40 years, on the grounds that he is an old idiot and therefore favored by Fortune. As a last attempt to settle the question of marriage, Pantagruel and Panurge take a sea voyage to consult the Oracle of Bacbuc ("Divine Bottle"). Their ship is well-provisioned with the phallic herb Pantagruelion, for which Rabelais gives a ribald natural history.

The Fourth Book

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The sea voyage continues for the whole of The Fourth Book of Pantagruel (in French, Le quart-livre de Pantagruel; the original title is Le quart livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel[4]). The whole book can be seen as a comical retelling of the Odyssey, or of the story of Jason and the Argonauts. In The Fourth Book, perhaps his most satirical, Rabelais criticizes what he perceived as the arrogance and wealth of the Roman Catholic Church, the political figures of the time, and popular superstitions, and he addresses several religious, political, linguistic, and philosophical issues.

The group sails to East Asia and buys many exotic animals. Panurge quarrels with the sheep merchant Dingdong, and takes his revenge by drowning him and his flock. They pass by the islands of the Bailiffs, whose peasants charge to be beaten. During a terrible storm at sea, Panurge is paralyzed with fear but feigns insufferable bravura afterwards. After slaying a sea-monster and being informed of the death of the giant Lent, they arrive at Wild Island, where the half-sausage inhabitants (called Chitterlings) mistake Pantagruel for their enemy Lent and attack.

The battle is stopped by a divine winged pig, who excretes mustard on the battlefield. They proceed to Ruach, whose people eat air, to barren Pope-Figland where a farmer and his wife outwit the devil, and to the arrogantly Catholic Papimania, where the people worship the Pope and his Decretals. After sailing through a cloud of frozen words and sounds, they come to an island that worships Gaster, the god of food. The book ends when Pantagruel fires a salute at the island of the Muses, and Panurge befouls himself for fear of the sound, and of the "celebrated cat Rodilardus".

The Fifth Book

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Fifth Book of Pantagruel (in French, Le cinquième-livre de Pantagruel; the original title is Le cinquiesme et dernier livre des faicts et dicts héroïques du bon Pantagruel[4]), was published posthumously around 1564, and chronicles the further journeyings of Pantagruel and his friends. At Ringing Island, the company find birds living in the same hierarchy as the Catholic church.

On Tool Island, the people are so fat they slit their skin to allow the fat to puff out. At the next island they are imprisoned by Furred Law-Cats, and escape only by answering a riddle. Nearby, they find an island of lawyers who nourish themselves on protracted court cases. In the Queendom of Whims, they uncomprehendingly watch a living-figure chess match with the miracle-working and prolix Queen Quintessence.

Passing by the abbey of the sexually prolific Semiquavers, and the Elephants and monstrous Hearsay of Satin Island, they come to the realms of darkness. Led by a guide from Lanternland, they go deep below the earth to the oracle of Bacbuc. After much admiring of the architecture and many religious ceremonies, they come to the sacred bottle itself. It utters the one word "trinc". After drinking liquid text from a book of interpretation, Panurge concludes wine inspires him to right action, and he forthwith vows to marry as quickly and as often as possible.

The last volume's attribution to Rabelais is debatable. The Fifth Book was not published until nine years after his death and includes much material that is clearly borrowed (such as from Lucian's True History and Francesco Colonna's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili[8]) or of lesser quality than the previous books. In the notes to his translation of Gargantua and Pantagruel, Donald M. Frame proposes that the Fifth Book may have been formed from unfinished material that a publisher later patched together. This interpretation has been largely supported by Mireille Huchon in "Rabelais Grammairien",[9] the first book to provide a rigorous grammatical analysis of the matter.

J.M.Cohen, in his Introduction to the Penguin Classics edition, states that chapters 17-48 were written by another hand using notes left by Rabelais and the general drift of what Rabelais had written of the Fifth Book.

Analysis

Bakhtin's analysis of Rabelais

|

|

Mikhail Bakhtin's book Rabelais and His World explores Gargantua and Pantagruel and is considered a classic of Renaissance studies.[10] Bakhtin declares that for centuries Rabelais' book had been misunderstood. Throughout Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin attempts two things. Firstly, to recover sections of Gargantua and Pantagruel that in the past were either ignored or suppressed. Secondly, to conduct an analysis of the Renaissance social system in order to discover the balance between language that was permitted and language which was not.[11]

Through this analysis, Bakhtin pinpoints two important subtexts in Rabelais' work: the first is carnivalesque which Bakhtin describes as a social institution, and the second is grotesque realism, which is defined as a literary mode. Thus, in Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin studies the interaction between the social and the literary, as well as the meaning of the body.[11]

Bakhtin explains that carnival in Rabelais' work and age is associated with the collectivity, for those attending a carnival do not merely constitute a crowd. Rather the people are seen as a whole, organized in a way that defies socioeconomic and political organization.[12] According to Bakhtin, "[A]ll were considered equal during carnival. Here, in the town square, a special form of free and familiar contact reigned among people who were usually divided by the barriers of caste, property, profession, and age".[13]

At carnival time, the unique sense of time and space causes the individual to feel he is a part of the collectivity, at which point he ceases to be himself. It is at this point that, through costume and mask, an individual exchanges bodies and is renewed. At the same time there arises a heightened awareness of one's sensual, material, bodily unity and community.[12]

Bakhtin says also that in Rabelais the notion of carnival is connected with that of the grotesque. The collectivity partaking in the carnival is aware of its unity in time as well as its historic immortality associated with its continual death and renewal. According to Bakhtin, the body is in need of a type of clock if it is to be aware of its timelessness. The grotesque is the term used by Bakhtin to describe the emphasis of bodily changes through eating, evacuation, and sex: it is used as a measuring device.[14]

Translations

Thomas Urquhart first translated the work into English in the mid-17th century, although his translation was incomplete, and Peter Anthony Motteux completed the translation of the fourth and fifth books. The Urquhart/Motteux version is far from literal, but Urquhart's work was described by J. M. Cohen in the preface to his 1955 translation as "more like a brilliant recasting and expansion than a translation", although Motteux's contribution was criticised as "no better than competent hackwork... [W]here Urquhart often enriches, he invariably impoverishes". The Urquhart/Motteaux translation is out of copyright, and so it has been used for many reprinted editions, including that of Britannica's Great Books of the Western World.

William Francis Smith (1842–1919) made a new translation in 1893, trying to match Rabelais' sentence forms exactly, which renders the English obscure in places. For example, the convent prior exclaims against Friar John when the latter bursts into the chapel,

What will this drunken Fellow do here? Let one take me him to prison. Thus to disturb divine Service!

Smith's version includes copious notes.

John Michael Cohen's modern translation, first published in 1955 by Penguin, "admirably preserves the frankness and vitality of the original", according to its back cover, although it provides limited explanation of Rabelais' word-plays and allusions.

Penguin published a translation by M. A. Screech in 2006 with an explanatory section preceding each chapter and brief footnotes explaining some of the allusions and puns used.[15]

Illustrations

The most famous and reproduced illustrations for Gargantua and Pantagruel were done by French artist Gustave Doré and published in 1854.[16] Several appear in this article. Over 400 additional drawings were done by Doré for the 1873 second edition of the book. An edition published in 1904 was illustrated by W. Heath Robinson.[17] Another set of illustrations was done by French artist Joseph Hémard and published in 1922.[18]

See also

- List of fictional works in Gargantua and Pantagruel

- Abbey of Thelema

- Mammotrectus super Bibliam – criticised in Gargantua

- Mirapolis, a former French theme park with Gargantua as icon

- Perrin Dandin, a character from the Third Book

- Raven Tales

- The Golden Axe

References

- ↑ Rabelais, François (1952). "Biographical Note". Rabelais. Great Books of the Western World. 24. Robert Maynard Hutchins (editor-in-chief), Mortimer J. Adler (associate editor), Sir Thomas Urquhart (translator), Peter Motteux (translator). Chicago, USA: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ↑ Le Cadet, Nicolas (2009) Marcel De Grève, La réception de Rabelais en Europe du XVIe au XVIIIe siècle, Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes, Comptes rendus (par année de publication des ouvrages), 2009, [En ligne], mis en ligne le 20 avril 2010. Consulté le 22 novembre 2010.

- ↑ Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and his World. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1984. p. 110.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rabelais, François; Jacques Boulenger (1955). Rabelais Oeuvres Complètes. France: Gallimard. p. 1033.

- ↑ Brett Bodemer. "Rabelais and the Abbey of Saint-Victor Revisited." Information & Culture: A Journal of History 47.1 (2012): 4–17

- ↑ Gargantua and Pantagruel, Rabelais, Urquhart translation, Chapters 1.VII and VIII

- ↑ Urquhart, Chapter 1.XI

- ↑ Marcel Francon, "Francesco Colonna's 'Poliphili Hypnerotomachia' and Rabelais", The Modern Language Review, Vol. 50, No. 1 (January 1955), pp. 52–55

- ↑ "Rabelais grammairien. De l'histoire du texte aux problèmes d'authenticité", Mirelle Huchon, in Etudes Rabelaisiennes XVI, Geneva, 1981

- ↑ Clark and Holquist, p. 295

- 1 2 Clark and Holquist, pp. 297–299

- 1 2 Clark and Holquist, p. 302

- ↑ Bakhtin, p. 10

- ↑ Clark and Holquist, p. 303

- ↑ Rabelais, François (2006). Gargantua and Pantagruel. Translated by M. A. Screech. Penguin Books. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ J. Bry Ainé, Paris, 1854.

- ↑ The Works of Mr. Francis Rabelais published by Grant Richards, London, 1904. Reprinted by The Navarre Society, London, 1921

- ↑ Crès, Paris, 1922.

Further reading

- The series in the original French is entitled La Vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel. Available English translations include The Complete Works of François Rabelais by Donald M. Frame and Five Books of the Lives, Heroic Deeds and Sayings of Gargantua and Pantagruel, translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and Pierre Antoine Motteux.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and his world, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1941.

- Clark, Katerina; Holquist, Michael (1984). Mikhail Bakhtin (4 ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-674-57417-5. Retrieved 2012-01-15.

- Holquist, Michael. Dialogism: Bakhtin and His World, Second Edition. Routledge, 2002.

- Kinser, Samuel. Rabelais's Carnival: Text, Context, Metatext. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990 1990.

- Shepherd, Richard Herne. The School of Pantagruel, 1862. Charles Collett. (Essay, transcription)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pantagruel. |

- Gargantua and Pantagruel at Project Gutenberg, translated by Sir Thomas Urquhart and illustrated by Gustave Doré.

-

Gargantua and Pantagruel public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Gargantua and Pantagruel public domain audiobook at LibriVox