Wakhan Corridor

| Wakhan Corridor | |||||||||

Wakhan Corridor | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 瓦罕走廊 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 瓦罕走廊 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Wakhan Corridor | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 阿富汗走廊 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 阿富汗走廊 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Afghan Corridor | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 瓦罕帕米尔 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 瓦罕帕米爾 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Wakhan Pamir | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dari name | |||||||||

| Dari | دهلېز واخان | ||||||||

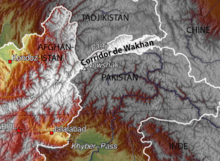

The Wakhan Corridor (alternatively Vakhan Corridor, or Wakhan) is the narrow strip of territory in northeastern Afghanistan that extends to China and separates Tajikistan from Pakistan and Kashmir. The corridor, wedged between the Pamir Mountains to the north and the Karakoram range to the south, is about 350 km (220 mi) long and 13–65 kilometres (8–40 mi) wide.[1] From this high mountain valley the Panj and Pamir Rivers emerge and form the Amu Darya. A trade route through the valley has been used by travelers going to and from East, South and Central Asia since antiquity. The term Wakhan Corridor can also refer to this constituent valley and the historical trade route through it. The closure of the Afghan-Chinese border crossing at the Wakhjir Pass on the east end of the Wakhan Corridor, has left the valley bereft of trade.

As of 2010, the Wakhan Corridor had 12,000 inhabitants.[2] The northern part of the Wakhan is also referred to as the Pamir.[3]

Geography

The Wakhan Corridor forms the panhandle of Afghanistan's Badakhshan Province. At its western entrance near the Afghan town of Ishkashim, the corridor is 18 km (11 mi) wide.[1] The western third of the corridor varies from 13–30 km (8–19 mi) in width and widens to 65 km (40 mi) in the central Wakhan.[1] At its eastern end, the corridor forks into two prongs that wrap around a salient of Chinese territory, forming the two countries' 92 km (57 mi) boundary.[1] The Wakhjir Pass, on the southeastern prong is about 300 km (190 mi) from Ishkashim.[1] The easternmost point of the northeastern prong is about 350 km (220 mi) from Ishkashim.[1] On the Chinese side of the border is Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

The northern border is formed by the Pamir River and Lake Zorkul in the west and the high peaks of the Pamir Mountains in the east. To the north is Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous region.

In the south, the corridor is bounded by the high mountains of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram. The Broghol and Irshad Passes along the southern flank offer access, respectively, to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Gilgit Baltistan on Pakistan's side of the border. The Dilisang Pass is disused.[5]

The corridor is higher in the east (the Wakhjir Pass is 4,923 m (16,152 ft) in elevation) and descends to about 3,037 m (9,964 ft) at Ishkashim.[6] The Wakhjir River emerges from an ice cave on the Afghan side of the Wakhjir Pass and flows west, joining the Bozai Darya near the village of Bozai Gumbaz and forms the Wakhan River. The Wakhan River then joins the Pamir River near Kala-i-Panj to form the Panj River, which then flows out of the Wakhan Corridor at Ishkashim.

The Chinese consider the valley east of Wakhjir Pass on the Chinese side connecting Taghdumbash Pamir to be part of Wakhan Corridor. The high mountain valley is about 100 km (60 mi) long.[7][8] This valley, through which the Tashkurgan River flows, is generally about 3–5 km (2–3 mi) wide and less than 1 km (0.6 mi) at its narrowest point.[7] This entire valley on the Chinese side is closed to visitors; however, local residents and herders from the area are permitted access.[9]

History

Although the terrain is extremely rugged, the Corridor was historically used as a trading route between Badakhshan and Yarkand.[10] It appears that Marco Polo came this way.[11] The Portuguese Jesuit priest Bento de Goes crossed from the Wakhan to China between 1602 and 1606. In May 1906, Sir Aurel Stein explored the Wakhan and reported that at that time, 100 pony loads of goods crossed annually to China.[12] There were further crossings in 1874 by Captain T.E. Gordon of the British Army,[13] in 1891 by Francis Younghusband,[14] and in 1894 by Lord Curzon.[15]

Early travellers used one of three routes:

- A northern route led up the valley of the Pamir River to Zorkul Lake, then east through the mountains to the valley of the Murghab River, then across the Sarikol Range to China.

- A southern route led up the valley of the Wakhan River to the Wakhjir Pass to China. This pass is closed for at least five months a year and is only open irregularly for the remainder.[16]

- A central route branched off the southern route through the Little Pamir to the Murghab River valley.

The corridor is in part a political creation from The Great Game between the United Kingdom and Russian Empire. In the north, an agreement between the empires in 1873 effectively split the historic region of Wakhan by making the Panj and Pamir Rivers the border between Afghanistan and the Russian Empire.[1]. In the south, the Durand Line agreement of 1893 marked the boundary between British India and Afghanistan. This left a narrow strip of land ruled by Afghanistan as a buffer between the two empires, which became known as the Wakhan Corridor in the 20th century.[17]

The corridor has been closed to regular traffic for over a century[6] and there is no modern road. There is a rough road from Ishkashim to Sarhad-e Broghil[18] built in the 1960s,[19] but only rough paths beyond. These paths run some 100 km (60 mi) from the road end to the Chinese border at Wakhjir Pass, and further to the far end of the Little Pamir.

Jacob Townsend has speculated on the possibility of drug smuggling from Afghanistan to China via the Wakhan Corridor and Wakhjir Pass, but concluded that due to the difficulties of travel and border crossings, it would be minor compared to that conducted via Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province or through Pakistan, both having much more accessible routes into China.[20]

The government of Afghanistan has asked the People's Republic of China on several occasions to open the border in the Wakhan Corridor for economic reasons or as an alternative supply route for fighting the Taliban insurgency. The Chinese have resisted, largely due to unrest in its far western province of Xinjiang, which borders the corridor.[21][22] In December 2009, it was reported that the United States had asked China to open the corridor.[23]

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 International Boundary Study of the Afghanistan–USSR Boundary (1983) by the US Bureau of Intelligence and Research Pg. 7

- ↑ Wong, Edward (27 October 2010). "In Icy Tip of Afghanistan, War Seems Remote". The New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2010.

- ↑ Aga Khan Development Network (2010): Wakhan and the Afghan Pamir p.3

- ↑ "Lake Victoria, Great Pamir, May 2nd, 1874"

- ↑ The pass was crossed by a couple in 1950 and by a couple in 2004. See J.Mock and K. O'Neil: Expedition Report

- 1 2 FACTBOX-Key facts about the Wakhan Corridor. Reuters. June 12, 2009

- 1 2 "新疆边境行:记者抵达瓦罕走廊中方最西端(图)_新闻中心_新浪网" [Xinjiang Border Tour: Reporter arrived at the Chinese westernmost point of Wakhan Corridor]. news.sina.com.cn (in Chinese). Global Times. 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ↑ (Chinese) 小资料:瓦罕走廊 2009-05-05

- ↑ 环球时报 (2009-05-07). "《环球时报》记者组在瓦罕走廊感受中国边防". china.huanqiu.com (in Chinese). Global Times. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

由于瓦罕走廊没有开放旅游,普通游客走到这里便无法继续前行。...据他介绍,该派出所海拔3900米,辖区内户籍75户,约300人,到七八月夏季牧场开放时,山下牧民会到高海拔地区放牧,走廊人口将达到1800人左右。

- ↑ Stein, Mark Aurel (1907). Ancient Khotan. p. 32.

- ↑ The Travels of Marco Polo Book 1 Chapter 32

- ↑ Shahrani, M. Nazif (1979 and 2002) p.37

- ↑ Keay, J. (1983). When Men and Mountains Meet. pp. 256–7. ISBN 0-7126-0196-1.

- ↑ Younghusband, F. (1896, republished 2000) "The Heart of a Continent" ISBN 978-1-4212-6551-3

- ↑ "Geographical Journal" (July to September 1896)

- ↑ Townsend, J. (June 2005) China and Afghan Opiates: Assessing the Risk Chapter 4

- ↑ Jacobs, Frank (5 December 2011). "A Few Salient Points". The New York Times.

- ↑ J. Mock and K. O'Neil (2004): Expedition Report

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme (2003) Wakhan Mission Report

- ↑ "China and Afghan Opiates: Assessing the Risk" (Chapter 4). June 2005

- ↑ Afghanistan tells China to open Wakhan corridor route. The Hindu. June 11, 2009 Archived January 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ China mulls Afghan border request. BBC News Online. June 12, 2009

- ↑ South Asia Analysis Group: Paper No. 3579, 31 December 2009 Archived June 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

Sources

- Shahrani, M. Nazif (2002). The Kirghiz and Wakhi of Afghanistan: Adaptation to Closed Frontiers and War (2nd ed.). University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98262-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wakhan Corridor. |

- CIA Relief Map

- Wakhan Development Partnership, a project working to improve the lives of the people of Wakhan since 2003

- We Took the Highroad in Afghanistan National Geographic November 1950 - Story of the first modern crossing of the Wakhan Corridor by Westerners.

- A Short Walk in the Wakhan Corridor, article by Mark Jenkins in the November 2005 issue of Outside magazine

- Wakhan & the Afghan Pamir - In the footsteps of Marco Polo - Brochure of the region by Aga Khan Foundation

Coordinates: 37°N 73°E / 37°N 73°E