Palace of Inquisition

| Palace of Inquisition | |

|---|---|

| Palacio de la Inquisición | |

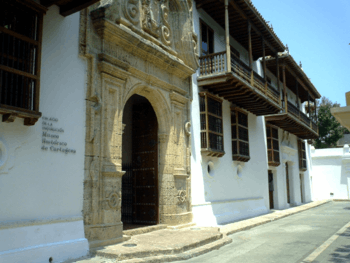

The Palace of Inquisition (photographed March 2006) | |

| Alternative names | Inquisition Palace |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Spanish Colonial, Baroque |

| Location | Cartagena, Colombia |

| Town or city | Cartagena |

| Country | Colombia |

| Coordinates | 10°25′22.47″N 75°33′4.88″W / 10.4229083°N 75.5513556°WCoordinates: 10°25′22.47″N 75°33′4.88″W / 10.4229083°N 75.5513556°W |

| Construction started | 1610 |

| Completed | c. 1770 |

| Owner | Colombian government |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 2 |

The Palace of Inquisition, also known as the Inquisition Palace, (Spanish: Palacio de la Inquisición) is an eighteenth-century the seat of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Cartagena, now in modern Colombia. Finished around 1770, it currently serves as a museum showcasing historical artifacts. The museum once displayed torture equipment used on victims during the inquisition however these items have been removed from display in 2015 prior to visits to Colombia by Pope Francis. It has been described as "one of the finer buildings" in Cartagena.[1] Cited as one of Cartagena's "best examples of late colonial, civil architecture", it faces the Parque de Bolívar.[2]

History

The establishment of the Palace was decreed by Philip III.[3] Since Cartagena was a center of commerce, a transit point between the Caribbean and Spanish settlements in western South America, the city became the third in the Spanish empire to have a tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Some merchants were Portuguese and suspected of being crypto-Jews (Jews passing as Christian). During the period 1580-1640, the crown of Portugal and that of Spain were ruled by the same monarch, and the period saw many Portuguese merchants active in Spain's overseas colonies. Established in 1610,[1] the current building was completed much later.[lower-alpha 1] The Palace was used by Inquisition to try Jews[6] and other non-Catholics[7] and about 800 individuals believed guilty of crimes such as black magic were publicly executed there.[1]

Architecture

The Palace is built in Spanish Colonial style,[4] with elements from the Baroque era.[1] A crucifix occupies one of the walls facing a torture equipment.[6] The white brick structure[8] has gateways made of stone.[1] The rooms of the Palace are mostly made up of masonry.[9] The framework of the Palace is built out of wood;[10] double-storey[5] limestones were also used in the making of the Palace.[11] The museum displays coins, maps, weapons, furniture, church bells, and depictions of notable generals, in addition to the torture equipment used previously.[12] The Palace was partially restored to preserve Colombia's cultural heritage.[10]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kohn, Michael (2006). Colombia. Ediz. Inglese (4 ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 129. ISBN 9781741042849.

- ↑ Viva Travel Guides Colombia. Viva Publishing Network. 2008. p. 227. ISBN 9780979126444.

- ↑ Kelemen, Kal (1967). Baroque and Rococo in Latin America. 1 (2 ed.). Dover Publications.

- 1 2 Cruise Travel. 9. Lakeside. July 1987. p. 25.

- 1 2 Melton, J. Gordon (2010). Religions of the World, Second Edition: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices (2 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 746. ISBN 9781598842043.

- 1 2 Arbell, Mordehay (2002). The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean: The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas. Gefen. p. 309. ISBN 9789652292797.

- ↑ Cruise Travel. August 1982. p. 44.

- ↑ Ebony. April 1968. p. 131.

- ↑ Coghlan, Nicholas (2004). Saddest Country: On Assignment in Colombia. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 41. ISBN 9780773527874.

- 1 2 "Museo Histórico de Cartagena de Indias - Palacio de la Inquisición" (in Spanish). Cartagena de Indias. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Historia" (in Spanish). Musueo Historico de Cartagena. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- ↑ The Rotarian. 128. March 1976. p. 31.