Northrop P-61 Black Widow

| P-61 Black Widow | |

|---|---|

| |

| A P-61A of 419th Night Fighter Squadron | |

| Role | Night fighter |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Northrop |

| First flight | 26 May 1942 |

| Introduction | 1944 |

| Retired | 1954 |

| Primary users | United States Army Air Forces United States Air Force |

| Number built | 706 |

| Unit cost |

US$190,000[1] |

| Variants | Northrop F-15 Reporter |

The Northrop P-61 Black Widow, named for the American spider, was the first operational U.S. warplane designed as a night fighter, and the first aircraft designed to use radar.[2][3] The P-61 had a crew of three: pilot, gunner, and radar operator. It was armed with four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano M2 forward-firing cannons mounted in the lower fuselage, and four .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns mounted in a remote-controlled dorsal gun turret.

It was an all-metal, twin-engine, twin-boom design developed during World War II.[4] The first test flight was made on May 26, 1942, with the first production aircraft rolling off the assembly line in October 1943. The last aircraft was retired from government service in 1954.

Although not produced in the large numbers of its contemporaries, the Black Widow was effectively operated as a night-fighter by United States Army Air Forces squadrons in the European Theater, Pacific Theater, China Burma India Theater, and Mediterranean Theater during World War II. It replaced earlier British-designed night-fighter aircraft that had been updated to incorporate radar when it became available. After the war, the P-61—redesignated the F-61—served in the United States Air Force as a long-range, all-weather, day/night interceptor for Air Defense Command until 1948, and Fifth Air Force until 1950.

On the night of 14 August 1945, a P-61B of the 548th Night Fight Squadron named Lady in the Dark was unofficially credited with the last Allied air victory before VJ Day.[5] The P-61 was also modified to create the F-15 Reporter photo-reconnaissance aircraft for the United States Army Air Forces and subsequently used by the United States Air Force.[6]

Development

Origins

In August 1940, 16 months before the United States entered the war, the U.S. Air Officer in London, Lieutenant General Delos C. Emmons, was briefed on British research in radar (RAdio Detection And Ranging), which had been underway since 1936 and had played an important role in the nation's defense against the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain. General Emmons was informed of the new Airborne Intercept radar (AI for short), a self-contained unit that could be installed in an aircraft and allow it to operate independently of ground stations. In September 1940, the Tizard Mission traded British research on many aspects including radar for American production.

Simultaneously, the British Purchasing Commission evaluating US aircraft declared their urgent need for a high-altitude, high-speed aircraft to intercept the Luftwaffe bombers attacking London at night. The aircraft would need to patrol continuously over the city throughout the night, requiring at least an eight-hour loiter capability. The aircraft would carry one of the early (and heavy) AI radar units, and mount its specified armament in "multiple-gun turrets". The British conveyed the requirements for a new fighter to all the aircraft designers and manufacturers they were working with. Jack Northrop was among them, and he realized that the speed, altitude, fuel load and multiple-turret requirements demanded a large aircraft with multiple engines.

General Emmons returned to the U.S. with details of the British night-fighter requirements, and in his report said that the design departments of the Americans' aviation industry's firms possibly could produce such an aircraft. The Emmons Board developed basic requirements and specifications, handing them over towards the end of 1940 to Air Technical Service Command (ATSC) at Wright Field, Ohio. After considering the two biggest challenges—the high weight of the AI radar and the very long (by fighter standards) loiter time of eight hours minimum—the board, including Jack Northrop, realized the aircraft would need the considerable power and resulting size of twin engines, and recommended such parameters. The United States had two twin-row radials of at least 46 liters displacement in development since the late 1930s; the Double Wasp and the Duplex Cyclone. These engines had been airborne for their initial flight tests by the 1940/41 timeframe, and were each capable, with more development, of exceeding 2,000 hp (1,491 kW).

Vladimir H. Pavlecka, Northrop Chief of Research, was present on unrelated business at Wright Field. On 21 October 1940, Colonel Laurence Craigie of the ATSC phoned Pavlecka, explaining the U.S. Army Air Corps' specifications, but told him to "not take any notes, 'Just try and keep this in your memory!'"[7] What Pavlecka did not learn was radar's part in the aircraft; Craigie described the then super-secret radar as a "device which would locate enemy aircraft in the dark" and which had the capability to "see and distinguish other airplanes." The mission, Craigie explained, was "the interception and destruction of hostile aircraft in flight during periods of darkness or under conditions of poor visibility."

Pavlecka met with Jack Northrop the next day, and gave him the USAAC specification. Northrop compared his notes with those of Pavlecka, saw the similarity between the USAAC's requirements and those issued by the RAF, and pulled out the work he had been doing on the British aircraft's requirements. He was already a month along, and a week later, Northrop pounced on the USAAC proposal.

On 5 November, Northrop and Pavlecka met at Wright Field with Air Material Command officers and presented them with Northrop's preliminary design. Douglas' XA-26A night fighter proposal was the only competition, but Northrop's design was selected and the Black Widow was conceived.

Early stages

Following the USAAC acceptance, Northrop began comprehensive design work on the aircraft to become the first to design a dedicated night fighter. The result was the largest and one of the most deadly pursuit-class aircraft flown by the U.S. during the war.

Jack Northrop's first proposal was a long fuselage gondola between two engine nacelles and tail booms. Engines were Pratt & Whitney R-2800-10 Double Wasp 18-cylinder radials, producing 2,000 hp (1,491 kW) each. The fuselage housed the three-man crew, the radar, and two four-gun turrets. The .50 in (12.7 mm) AN/M2 M2 Browning machine guns were fitted with 36 in (91 cm) long, lightweight "aircraft" barrels with perforated sleeves, without the heavy, breech-end cooling collar of the "M2HB" Browning .50-cal ordnance. The turrets were located in the nose and rear of the fuselage. It stood on tricycle landing gear and featured full-span retractable flaps, or "Zap flaps" (named after aircraft engineer Edward Zaparka) in the wings.

The aircraft was huge, as Northrop had anticipated. While far heavier and larger multi-engine bombers existed, its 45.5 ft (14 m) length, 66 ft (20 m) wingspan and projected 22,600 lb (10,251 kg) full-load weight were unheard of for a fighter, making the P-61 hard for many to accept as a feasible fighter aircraft.

Changes to the plan

Some alternative design features were investigated before finalization. Among them were conversion to a single vertical stabilizer/rudder and the shifting of the nose and tail gun turrets to the top and bottom of the fuselage along with the incorporation of a second gunner.

Late in November 1940, Jack Northrop returned to the crew of three and twin tail/rudder assembly. To meet USAAC's request for more firepower, designers abandoned the ventral turret and mounted four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano M2 cannons in the wings. As the design evolved, the cannons were subsequently repositioned in the belly of the aircraft. The P-61 therefore became one of the few U.S.-designed fighter aircraft to have a quartet of 20 mm (.79 in) cannon — along with the NA-91 version of the Mustang and the U.S. Navy's uprated F4U-4C Corsair as factory-standard in World War II.

Northrop Specification 8A was formally submitted to Army Air Material Command at Wright Field, on 5 December 1940. Following a few small changes, Northrop's NS-8A fulfilled all USAAC requirements, and the Air Corps issued Northrop a Letter of Authority For Purchase on 17 December. A contract for two prototypes and two scale models to be used for wind tunnel testing (costs not to exceed $1,367,000), was awarded on 10 January 1941. Northrop Specification 8A became, by designation of the War Department, the XP-61.

XP-61 development

In March 1941, the Army/Navy Standardization Committee decided to standardize use of updraft carburetors across all U.S. military branches. The XP-61, designed with downdraft carburetors, faced an estimated minimum two-month redesign of the engine nacelle to bring the design into compliance. The committee later reversed the updraft carburetor standardization decision (the XP-61 program's predicament likely having little influence), preventing a potential setback in the XP-61's development.

The Air Corps Mockup Board met at Northrop on 2 April 1941, to inspect the XP-61 mock-up. They recommended several changes following this review. Most prominently, the four 20 mm (.79 in) M2 cannons were relocated from the outer wings to the belly of the aircraft, clustered tightly with the forward-facing ventral "step" in the fuselage to accommodate them placed just behind the rear edge of the nose gear well. The closely spaced, centered installation, with two cannons stacked vertically, slightly outboard of the aircraft's centerline on each side, and the top cannon in each pair only a few inches farther outboard, eliminated the inherent drawbacks of the convergence of wing-mounted guns. Without convergence, aiming was considerably easier and faster, and the tightly grouped cannons created a thick stream of 20 mm (.79 in) projectiles. The removal of the guns and ammunition from the wings also cleaned up the wings' airfoil and increased internal fuel capacity from 540 gal (2,044 l) to 646 gal (2,445 l).

Other changes included the provision for external fuel carriage in drop tanks, flame arrestors/dampers on engine exhausts, and redistribution of some radio equipment. While all beneficial from a performance standpoint—especially the relocation of the cannons—the modifications required over a month of redesign work, and the XP-61 was already behind schedule.

In mid-1941, the dorsal turret mount finally proved too difficult to install in the aircraft, and was changed from the General Electric ring mount to a pedestal mount like that used for the upper turrets in Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresss, Consolidated B-24 Liberators, North American B-25 Mitchells, Douglas A-20s, and other American bombers. Following this modification, the turret itself became unavailable, as operational aircraft, in this case the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, were ahead of experimental aircraft in line for the high-demand component. For flight testing, engineers used a dummy turret.

During February 1942, subcontracting manufacturer Curtiss notified Northrop that the C5424-A10 four-bladed, automatic, full-feathering propeller Northrop had planned for use in the XP-61 would not be ready for the prototype rollout or the beginning of flight tests. Hamilton Standard propellers were used in lieu of the Curtiss props until the originally planned component became available.

The XP-61's weight rose during construction of the prototype, to 22,392 lb (10,157 kg) empty and 29,673 lb (13,459 kg) at takeoff. Engines were R-2800-25S Double Wasp radials; turning 12 ft 2 in diameter Curtiss C5425-A10 four-blade propellers, both rotating counterclockwise when viewed from the front. Radios included two command radios, SCR-522As, and three other radio sets, the SCR-695A, AN/APG-1, and AN/APG-2. Central fire control for the gun turret was similar to that used on the B-29, the General Electric GE2CFR12A3.

P-61C

The P-61C was a high-performance variant designed to rectify some of the combat deficiencies encountered with the A and B variants. Work on the P-61C proceeded quite slowly at Northrop because of the higher priority of the Northrop XB-35 flying wing strategic bomber project. In fact, much of the work on the P-61C was farmed out to Goodyear, which had been a subcontractor for production of Black Widow components. It was not until early 1945 that the first production P-61C-1-NO rolled off the production lines. As promised, the performance was substantially improved in spite of a 2,000 lb (907 kg) increase in empty weight. Maximum speed was 430 mph (690 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,000 m), service ceiling was 41,000 ft (12,500 m), and an altitude of 30,000 ft (9,000 m) could be attained in 14.6 minutes.

The P-61C was equipped with perforated fighter airbrakes located both below and above the wing surfaces. These were to provide a means of preventing the pilot from overshooting his target during an intercept. For added fuel capacity, the P-61C was equipped with four underwing pylons (two inboard of the nacelles, two outboard) which could carry four 310 gal (1,173 l) drop tanks. The first P-61C aircraft was accepted by the USAAF in July 1945. However, the war in the Pacific ended before any P-61Cs could see combat. The 41st and last P-61C-1-NO was accepted on 28 January 1946. At least 13 more were completed by Northrop, but were scrapped before they could be delivered to the USAAF.

Service life of the P-61C was quite brief, since its performance was being outclassed by newer jet aircraft. Most were used for test and research purposes. By the end of March 1949 most P-61Cs had been scrapped. Two entered the civilian market and two others went to museums.

F-15/RF-61C

In mid-1945, the surviving XP-61E was modified into an unarmed photographic reconnaissance aircraft. All the guns were removed, and a new nose was fitted, capable of holding an assortment of aerial cameras. The aircraft, redesignated XF-15, flew for the first time on 3 July 1945. A P-61C was also modified to XF-15 standards. Apart from the turbosupercharged R-2800-C engines, it was identical to the XF-15 and flew for the first time on 17 October 1945. The nose for the F-15A was subcontracted to the Hughes Tool Company of Culver City, California. The F-15A was basically the P-61C with the new bubble-canopy fuselage and the camera-carrying nose, but without the fighter brakes on the wing.

F2T-1N

The United States Marine Corps had planned to acquire 75 Black Widows, but these were canceled in 1944 in favor of the Grumman F7F Tigercat. In September 1945, however, the Marines received a dozen former Air Force P-61Bs to serve as radar trainers until the Tigercats would be available in squadron strength.[8] Designated F2T-1N[9] these aircraft were assigned to shore-based Marine units and served briefly, the last two F2T-1s being withdrawn on 30 August 1947.

Design

The P-61 featured a crew of three: pilot, gunner, and radar operator. It was armed with four 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano M2 forward-firing cannons mounted in the lower fuselage, and four .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns lined up horizontally with the two middle guns slightly offset upwards in a remotely aimed dorsally mounted turret, a similar arrangement to that used with the B-29 Superfortress using four-gun upper forward remote turrets. The turret was driven by the General Electric GE2CFR12A3 gyroscopic fire control computer, and could be directed by either the gunner or radar operator, who both had aiming control and gyroscopic collimator sight assembly posts attached to their swiveling seats.

The two Pratt & Whitney R-2800-25S Double Wasp engines were each mounted approximately one-sixth out on the wing's span. Two-stage, two-speed mechanical superchargers were fitted. In an effort to save space and weight, no turbo-superchargers were fitted, despite the expected 50 mph (80 km/h) top speed and 10,000 ft (3,048 m) operational ceiling increases.

Main landing gear bays were located at the bottom of each nacelle, directly behind the engine. The two main gear legs were each offset significantly outboard in their nacelles, and retracted towards the tail; oleo scissors faced forwards. Each main wheel was inboard of its gear leg and oleo. Main gear doors were two pieces, split evenly, longitudinally, hinged at inner door's inboard edge and the outer door's outboard edge.

Each engine cowling and nacelle drew back into tail booms that terminated upwards in large vertical stabilizers and their component rudders, each of a shape similar to a rounded right triangle. The leading edge of each vertical stabilizer was faired smoothly from the surface of the tail boom upwards, swept back to 37°. The horizontal stabilizer extended between the inner surfaces of the two vertical stabilizers, and was approximately ¾ the chord of the wing root, including the elevator. The elevator spanned approximately ⅓ of the horizontal stabilizer's width, and in overhead plan view, angled inwards in the horizontal from both corners of leading edge towards the trailing edge approximately 15°, forming the elevator into a wide, short trapezoid. The horizontal stabilizer and elevator assembly possessed a slight airfoil cross-section.

The engines and nacelles were outboard of the wing root and a short "shoulder" section of the wing that possessed a 4° dihedral, and were followed by the remainder of the wing which had a dihedral of 2°. The leading edge of the wing was straight and perpendicular to the aircraft's centerline. The trailing edge was straight and parallel to the leading edge in the shoulder, and tapered forward 15° outboard of the nacelle. Leading edge updraft carburetor intakes were present on the wing shoulder and the root of the outer wing, with a few inches of separation from the engine nacelle itself. They were very similar in appearance to those on the F4U Corsair—thin horizontal rectangles with the ends rounded out to nearly a half-circle, with multiple vertical vanes inside to direct the airstream properly.

The P-61 did not have normal-sized ailerons. Instead, it had small ailerons which allowed wider span flaps and a very low landing speed.[10] These ailerons, known as guide ailerons, gave some roll control and provided acceptable feel for the pilot in rolling manoeuvres. Control of the aircraft about the roll axis was augmented with circular-arc spoilerons which provided about half the roll control at low speeds and most of it at high speeds.[11] The spoilers were located outboard of the nacelle in front of the flaps.

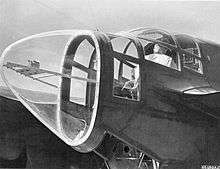

The main fuselage, or gondola, was centered on the aircraft's centerline. It was, from the tip of the nose to the end of the Plexiglas tail-cone, approximately five-sixths the length of one wing (root to tip). The nose housed an evolved form of the SCR-268 Signal Corps Radar, the Western Electric Company's SCR-720A. Immediately behind the radar was the multi-framed "greenhouse" canopy, featuring two distinct levels, one for the pilot and a second for the gunner above and behind him, the latter elevated by approximately 6 in (15 cm). Combined with the nearly flat upper surface of the aircraft's nose, the two-tiered canopy gave the aircraft's nose a distinct appearance of three wide, shallow steps. The forward canopy in the XP-61 featured contiguous, smooth-curved, blown-Plexiglas canopy sections facing forward, in front of the pilot and the gunner. The tops and sides were framed.

Beneath the forward crew compartment was the nose gear wheel well, through which the pilot and gunner entered and exited the aircraft. The forward gear leg retracted to the rear, up against a contoured cover that when closed for flight formed part of the cockpit floor; the gear would not have space to retract with it open. The oleo scissor faced forwards. The nosewheel was centered, with the strut forking to the aircraft's left. The nosewheel was approximately ¾ the diameter of the main wheels. Nose gear doors were two pieces, split evenly longitudinally, and hinged at each outboard edge.

The center of the gondola housed the main wing spar, fuel storage, fuel piping and control mechanisms, control surface cable sections, propeller and engine controls, and radio/IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) equipment, but was predominantly occupied by the top turret mounting ring, rotation and elevation mechanisms, ammunition storage for the turret's machine guns, the GE2CFR12A3 gyroscopic fire control computer, and linkages to the gunner and radar operator's turret control columns, forward and aft, respectively.

The radar operator's station was at the aft end of the gondola. The radar operator controlled the SRC-720 radar set and viewed its display scopes from the isolated rear compartment, which he entered by way of a small hatch with a built-in ladder on the underside of the aircraft. In addition to the radar systems themselves, the radar operator had intercom and radio controls, as well as the controls and sight for the remote turret. The compartment's canopy followed the curvature of the gondola's rear section, with only a single rounded step to the forward canopy's double step. The rear of the gondola was enclosed by a blown Plexiglas cap that tapered quickly in overhead plan view to a barely rounded point; the shape was somewhat taller in side profile than it was in overhead plan view, giving the end of the "cone" a rounded "blade" appearance when viewed in perspective.

The cross-section of the gondola, front to back, was generally rectangular, vertically oriented. The tip of the nose was very rounded to accommodate the main AI radar's dish antenna, merging quickly to a rectangular cross-section that tapered slightly towards the bottom. This cross-section lost its taper but became clearly rounded at the bottom moving back through the forward crew compartment and nose gear well. Height increased at both steps in the forward canopy, with the second step being flush with the top of the aircraft (not counting the dorsal gun turret). At the rear of the forward crew compartment, the cross-section's bottom bulged downwards considerably and continued to do so until just past the midpoint between the rear of the forward crew compartment and the front of the rear crew compartment, where the lower curvature began to recede. Beginning at the front of the rear crew compartment, the top of the cross-section began to taper increasingly inwards above the aircraft's center of gravity when progressing towards the rear of the gondola. The cross-section rounded out considerably by the downward step in the rear canopy, and rapidly became a straight-sided oval, shrinking and terminating in the tip of the blown-Plexiglas "cone" described above.

The cross-section of the nacelles was essentially circular throughout, growing then diminishing in size when moving from the engine cowlings past the wing and gear bay, towards the tail booms and the vertical stabilizers. A bulge on the top of the wing maintained the circular cross-section as the nacelles intersected the wing. The cross-section became slightly egg-shaped around the main gear bays, larger at the bottom but still round. An oblong bulge on the bottom of the main gear doors, oriented longitudinally, accommodated the main wheels when the gear was retracted.

Wingtips, wing-to-nacelle joints, tips and edge of stabilizers and control surfaces (excluding the horizontal stabilizer and elevator) were all smoothly rounded, blended or filleted. The overall design was exceptionally clean and fluid as the aircraft possessed very few sharp corners or edges.

SCR-720 radar

The production model of the SCR-720A mounted a scanning radio transmitter in the aircraft nose; in Airborne Intercept mode, it had a range of nearly five miles (8 km). The unit could also function as an airborne beacon / homing device, navigational aid, or in concert with interrogator-responder IFF units. The XP-61's radar operator located targets on his scope and steered the unit to track them, vectoring and steering the pilot to the radar target via oral instruction and correction. Once within range, the pilot used a smaller scope integrated into the main instrument panel to track and close on the target.[12]

Remote turret

The XP-61's spine-mounted dorsal remote turret could be aimed and fired by the gunner or radar operator, who both had aiming control and gyroscopic collimator sighting posts attached to their swiveling seats, or could be locked forward to be fired by the pilot in addition to the 20 mm (.79 in) cannons. The radar operator could rotate the turret to engage targets behind the aircraft. Capable of a full 360° rotation and 90° elevation, the turret could be used to engage any target in the hemisphere above and to the sides of the XP-61. A brief assessment of the turret by the British Aeroplane & Armament Experimental Establishment in 1944 found problems with the aiming and "jerky movement" of the guns.[13]

Operational history

Training units

The first unit to receive production aircraft was the 348th Night Fighter Squadron at Orlando Army Air Base, Florida, which was responsible for training night fighter crews.[14]

P-61 crews trained in a variety of ways. Several existing night fighter squadrons operating in the Mediterranean and Pacific theatres were to transition directly into the P-61 from Bristol Beaufighters and Douglas P-70s, though most P-61 crews were to be made up of new recruits operating in newly commissioned squadrons. After receiving flight, gunnery or radar training in bases around the U.S., the crews were finally assembled and received their P-61 operational training in Florida for transfer to the European Theatre, or California for operations in the Pacific Theatre.

European Theater

The P-61 had an inauspicious start to its combat in the European theatre. Some believed the P-61 was too slow to effectively engage German fighters and medium bombers, a view which the RAF shared, based on the performance of a single P-61 they had received in early May.

The 422d Night Fighter Squadron was the first to complete their training in Florida and, in February 1944, the squadron was shipped to England aboard the RMS Mauretania. The 425th NFS soon followed aboard the RMS Queen Elizabeth.

The situation deteriorated in May 1944 when the squadrons learned that several USAAF generals - including General Hoyt Vandenberg - believed the P-61 was too slow to effectively engage in combat with German fighters and medium bombers. General Spaatz requested the de Havilland Mosquito night fighters to equip two U.S. night fighter squadrons based in the UK. The request was denied due to insufficient supplies of Mosquitoes which were in demand for a number of roles.[15]

At the end of May, the USAAF insisted on a competition between the Mosquito and the P-61 for operation in the European Theater. RAF crews flew the Mosquito Mk XVII while crews from the 422nd NFS flew the P-61. In the end the USAAF determined that the P-61 had a slightly better rate of climb and could turn more tightly than the Mosquito. Colonel Winston Kratz, director of night fighter training in the USAAF, had organized a similar competition earlier. He said of the results:

- I'm absolutely sure to this day that the British were lying like troopers. I honestly believe the P-61 was not as fast as the Mosquito, which the British needed because by that time it was the one airplane that could get into Berlin and back without getting shot down. I doubt very seriously that the others knew better. But come what may, the '61 was a good night fighter. In the combat game you've got to be pretty realistic about these things. The P-61 was not a superior night fighter. It was not a poor night fighter. It was a good night fighter. It did not have enough speed.[5]

However, on July 5, 1944 General Spaatz ordered a competition be held between the P-61 - using an example from the 422nd which had its Double Wasp radials carefully "tuned up" for the competition - against a Mosquito NF.XVII, and Lt.Col. Kratz made a $500 bet in favor of the Mosquito being a faster and more maneuverable night fighting platform. The "tweaked" P-61 proved Lt.Col. Kratz wrong, as according to the 422nd's squadron historian it "... proved faster at all altitudes, outturned the Mossie at every altitude and by a big margin and far surpassed the Mossie in rate of climb".[16]

In England, the 422d NFS finally received their first P-61s in late June, and began flying operational missions over England in mid-July. These aircraft arrived without the dorsal turrets so the squadron's gunners were reassigned to another NFS that was to continue flying the P-70. The first P-61 engagement in the European Theater occurred on July 15 when a P-61 piloted by Lt. Herman Ernst was directed to intercept a V-1 "Buzz Bomb." Diving from above and behind to match the V-1's 350 mph (560 km/h) speed, the P-61's plastic rear cone imploded under the pressure and the attack was aborted. The tail cones failed on several early P-61A models before this problem was corrected. On 16 July, Lt. Ernst was again directed to attack a V-1 and, this time, was successful, giving the 422nd NFS and the European Theater its first P-61 kill.

In early August 1944, the 422d NFS transferred to Maupertus, France, and began to encounter German aircraft for the first time. On the night of 14–15 August 1944, "Impatient Widow", tail number 42-5591 had its starboard engine shot out along with oil lines and hydraulics while attempting to intercept a Heinkel He 177A-5 of 5.Staffel/Kampfgeschwader 40, code F8+AN, Werknummer 550 077, flown by Hptm. Stolle. The downing was witnessed by two other Heinkels, occurring North of Barfleur, Normandy. A Bf 110 was shot down, and shortly afterwards, the squadron's commanding officer Lieutenant Colonel O. B. Johnson, his P-61 already damaged by anti aircraft land fire, shot down a Fw 190. The 425th NFS scored its first kill shortly afterwards.

In October 1944, a P-61 of the 422nd NFS, now operating out of an abandoned Luftwaffe airfield in Florennes, Belgium, encountered a Messerschmitt Me 163 attempting to land. The P-61 tried to intercept it but the rocket-powered aircraft was gliding too fast. A week later, another P-61 spotted a Messerschmitt Me 262, but was also unable to intercept the jet. On yet another occasion, a 422nd P-61 spotted a Messerschmitt Me 410 Hornisse flying at tree top level but, as they dove on it, the "Hornet" sped away and the P-61 was unable to catch it. Contrary to popular stories, no P-61 ever engaged in combat with a German jet or any of the late war advanced Luftwaffe aircraft.

The most commonly encountered and destroyed Luftwaffe aircraft types were Junkers Ju 188s, Junkers Ju 52s, Bf 110s, Fw 190s, Dornier Do 217s and Heinkel He 111s, while P-61 losses were limited to numerous landing accidents, bad weather, friendly and anti aircraft land fire. One researcher suggests 42-39515 may have been shot down by an Fw 190 of NSG 9.[17]

The absence of turrets and gunners in most European Theater P-61s presented several unique challenges. The 422nd NFS kept its radar operator in the rear compartment, meaning the pilot had no visual contact with the operator. As a result, several pilots continued flying their critically damaged P-61s under the mistaken belief that their radar operator was injured and unconscious, when in fact he had already bailed out. The 425th night fighter squadron moved the radar operator to the gunner's position behind the pilot. This provided an extra set of eyes up front and moved the aircraft's center of gravity about 15 in (38 cm) forward, changing the flight characteristics from slightly nose up to slightly nose down which improved the P-61's overall performance.

By December 1944, P-61s of the 422nd and 425th NFS were helping to repel the German offensive known as the Battle of the Bulge, with two flying cover over the town of Bastogne. Pilots of the 422nd and 425th NFS switched their tactics from night fighting to daylight ground attack, strafing German supply lines and railroads. The P-61's four 20 mm (.79 in) cannons proved effective in destroying German locomotives and trucks.

The 422nd NFS produced three ace pilots and two radar operators,[18] while the 425th NFS officially claimed none. Lt. Cletus "Tommy" Ormsby of the 425th NFS was officially credited with three victories. Ormsby was killed by friendly fire moments after attacking two Junkers Ju 87s on the night of 24 March 1945. His radar operator escaped with serious injuries, and was saved only by the quick actions of German surgeons. He later reported that they had successfully engaged and shot down both Ju 87s before being shot down themselves. This claim was corroborated by other 425th aircrew who were operating in the area at the time.[19]

Mediterranean Theater

In the Mediterranean Theater, most night fighter squadrons exchanged their aging Bristol Beaufighters for P-61s too late to achieve any kills in the "Black Widow."

CBI Theater

P-61s of the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater were responsible for patrolling a larger area than any night-fighter squadrons of the war. The P-61 arrived too late in the CBI Theater to have any significant impact, as most Japanese aircraft had already been transferred out of the CBI Theater by that time in order to participate in the defense of the Japanese Homeland.

Pacific Theater

The 6th NFS based on Guadalcanal received their first P-61s in early June 1944. The aircraft were quickly assembled and underwent flight testing as the pilots changed from the squadron's aging P-70s. The first operational P-61 mission occurred on 25 June, and the type scored its first kill on 30 June 1944 when a Japanese Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bomber was shot down.

In the summer of 1944, P-61s in the Pacific Theater saw sporadic action against Japanese aircraft. Most missions ended with no enemy aircraft sighted but when the enemy was detected they were often in groups, with the attack resulting in several kills for that pilot and radar operator, who would jointly receive credit for the kill.

In the Pacific Theater in 1945, P-61 squadrons struggled to find targets. One squadron succeeded in destroying a large number of Kawasaki Ki-48 "Lily" Japanese Army Air Force twin-engined bombers, another shot down several Mitsubishi G4M "Bettys," while another pilot destroyed two Japanese Navy Nakajima J1N1 "Irving" twin-engined fighters in one engagement but most missions were uneventful. Several Pacific Theater squadrons finished the war with no confirmed kills. The 550th could only claim a crippled B-29 Superfortress, shot down after the crew had bailed out having left the aircraft on autopilot.

On 30 January 1945, a lone P-61 performed a mission as part of the successful raid carried out by U.S. Army Rangers to free over 500 Allied POWs held by the Japanese at the Cabanatuan prison camp (Camp Pangatian) in the Philippines. As the Rangers crept up on the camp, a P-61 swooped low and performed aerobatics for several minutes. The distraction of the guards allowed the Rangers to position themselves, undetected within striking range of the camp.

Poet and novelist James Dickey flew 38 Pacific Theatre missions as a P-61 radar operator with the 418th Night Fighter Squadron, an experience that influenced his work, and for which he was awarded five Bronze Stars.[20] The 418th NFS produced the only US Army Air Force night fighter aces in the Pacific, a pilot-radar operator team.

Historian Warren Thompson wrote that "it is widely believed" that the last enemy aircraft destroyed in combat before the Japanese surrender was downed by a P-61B-2 named "Lady in the Dark" (s/n 42-39408) of the 548th NFS.[21] The aircraft piloted by Lt. Robert W. Clyde and R/O Lt. Bruce K. LeFord on 14/15 August 1945 claimed a Nakajima Ki-44 "Tojo." The destruction of the "Tojo" came without a shot being fired; after the pilot of the "Tojo" sighted the attacking P-61, he descended to wave-top level and began a series of evasive maneuvers. These ended with his aircraft striking the water and exploding. Lts. Clyde and LeFord were never officially credited with this possible final kill of the war.[22]

Credit for kills

Since pilots and radar operators did not always fly as a team, the kills of the pilot and radar operator were often different. On some occasions, a pilot or radar operator with only one or two kills would fly with a radar operator or pilot who was already an "ace."[19]

Summary

Though the P-61 proved itself capable against most German aircraft it encountered, it was outclassed by the new aircraft arriving in the last months of World War II. It also lacked external fuel tanks until the last months of the war,[21] an addition that would have extended its range and saved many doomed crews looking for a landing site in darkness and bad weather. External bomb loads would also have made the type more suitable for the ground attack role it soon took on in Europe. These problems were all addressed eventually, but too late to have the impact they might have had earlier in the war. The P-61 proved capable against all Japanese aircraft it encountered, but saw too few of them to make a significant difference in the Pacific war effort.[5]

Postwar military service

The useful life of the Black Widow was extended for a few years into the immediate postwar period due to the USAAF's problems in developing a useful jet-powered night/all-weather fighter.

In Europe, the United States Air Forces in Europe was organized on 7 August 1945. Its night fighter force was organized with the 415th NFS at AAF Station Nordholz on 2 October; the 417th NFS at AAF Kassel-Rothwesten on 20 August, and the 416th NFS at AAF Station Hörsching, Austria. The 414th, 422d and 425th became non-operational and their personnel were returned to the United States. The 414th's P-61s were transferred to the 416th which was equipped with British de Havilland Mosquitos. High-hour aircraft were scrapped and P-61s in excess of operational needs were mothballed at the Erding Air Depot, Germany. All of these units were inactivated by the end of 1946, personnel and most aircraft being assigned to the 52d Fighter Group. Excess and mothballed Black Widows at Erding were sent to reclamation at Oberpfaffenhofen Air Depot near Munich.

In the Pacific, the 426th, 427th 548th and 550th NFS were inactivated by the end of 1945. As part of the Occupation force in Japan, the 418th and 547th NFS were transferred from Okinawa and Ie Shima to Atsugi Airfield, Japan, and the 421st NFS was reassigned from Ie Shima to Itazuke Airfield, Japan. The 6th, 418th and 421st were all inactivated, their personnel and aircraft being consolidated under the 347th Fighter Group in February 1947. They became the 339th, 4th and 68th Fighter Squadrons respectively. The 419th in the Philippines and the 449th on Guam were both inactivated. Many P-61s in the Pacific that were deemed "war weary" met their fate at reclamation facilities established on Luzon.[23]

P-61s returned to the United States which were considered still operational were organized and allocated to the three new Major Commands established by the 21 March 1946 USAAF reorganization. All of these CONUS-based commands were allocated squadrons which were non-operational that had to be manned and equipped.[23]

To Strategic Air Command the 57th and 58th Reconnaissance Squadrons (Weather) were assigned P-61s. The 57th and 58th NFS had been initially part of Third Air Force, Continental Air Forces and were equipped with early-model P-61Bs that had been used for training pilots in California before being reassigned to Rapid City Army Air Base, South Dakota. Under Third Air Force they were engaged in Weather Reconnaissance training immediately after the war, but the rapid demobilization of the AAF led to the 57th being inactivated by the end of the year, and 58th followed suit in May 1946.[23]

Tactical Air Command was assigned the 415th NFS, and Air Defense Command was assigned the 414th and 425th NFS. The 414th was almost immediately transferred to TAC. Both the 414th and 415th were equipped and manned at Shaw Field, South Carolina and by early 1947 were operationally ready. The 414th was deployed to Caribbean Air Command for defense of the Panama Canal, and the 415th was deployed to Alaskan Air Command for long-range air defense against Soviet aircraft stationed across the Bering Sea in Siberia. Both of these squadrons were soon transferred to the overseas commands by TAC, and were redesignated as Fighter Squadrons.[23]

Air Defense Command organized its Black Widow units with the 425th NFS being reassigned to McChord Field, Washington and the new 318th Fighter Squadron at Mitchel Field, New York in May 1947. A month later, the 52d Fighter Group (with the 2d and 5th Fighter Squadrons) were returned from Germany. With the 52d operational, the 325th Fighter Group at McChord was reassigned to Hamilton Field, near San Francisco with the 317th and 318th squadrons. All of these squadrons were equipped with P-61Bs drawn from storage depots in the southwest. With the change in the USAF's aircraft designation system in June 1948, all P-61s became F-61s and all F-15As became RF-61Cs. Buzz Letters "FH" were assigned.[24]

Ejection seat experiments

A Black Widow participated in early American ejection seat experiments performed shortly after the war. The Germans had pioneered the development of ejection seats early in the war, the first-ever emergency use of an ejection seat having been made on 14 January 1942 by Helmut Schenk, a Luftwaffe test pilot, when he escaped from a disabled Heinkel He 280 V1. American interest in ejection seats during the war was largely a side-issue of the developmental work done on pusher aircraft such as the Vultee XP-54, the goal being to give the pilot at least some slim chance of clearing the tail assembly and the propeller of the aircraft in the case of an emergency escape, but little progress had been made since World War II era pusher aircraft development had never really gotten past the drawing board or the initial prototype stage. However, the development of high-speed jet-powered aircraft made the development of practical ejection seats mandatory.

Initially, an ejection seat was "borrowed" from a captured German Heinkel He 162 and was installed in a Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star in August 1945. However, it was decided that the single-seat P-80 would not be suitable for these tests, and it was decided to switch to a three-seat Black Widow. A P-61B-5-NO (serial number 42-39489) was modified for the tests, the ejection seat being fitted in the forward gunner's compartment. The aircraft was redesignated XP-61B for these tests (there having been no XP-61B prototype for the initial P-61B series). A dummy was used in the initial ejection tests, but on 17 April 1946, a volunteer, Sgt. Lawrence Lambert was successfully ejected from the P-61B at a speed of 302 mph (486 km/h) at 7,800 ft (2,380 m).[25] With the concept having been proven feasible, newer jet-powered aircraft were brought into the program, and the XP-61B was reconverted to standard P-61B configuration.

Thunderstorm project

The P-61 was heavily involved in the Thunderstorm Project (1946–1949) that was a landmark program dedicated to gathering data on thunderstorm activity. The project was a cooperative undertaking on the part of four U.S. government agencies: the U.S. Weather Bureau and the NACA (National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, later to become NASA), assisted by the U.S. Army Air Forces (the U.S. Air Force, after 1947) and Navy. Scientists from several universities also participated in the initiation, design, and conduct of the project. The project's goal was to learn more about thunderstorms and to use this knowledge to better protect civil and military airplanes that operated in their vicinity. The P-61's radar and particular flight characteristics enabled it to find and penetrate the most turbulent regions of a storm, and return crew and instruments intact for detailed study.

The Florida phase of the project in 1946 continued into a second phase carried out in Ohio during the summer of 1947. Results derived from this pioneering field study formed the basis of the scientific understanding of thunderstorms, and much of what was learned has been changed little by subsequent observations and theories. Data was collected for the first time from systematic radar and aircraft penetration of thunderstorms, forming the basis of many published studies that are still frequently referenced by mesoscale and thunderstorm researchers.

Naval tests

P-61B-1NO, AAF Serial Number 42-39458, was operated by the U.S. Navy at the Patuxent River test facility in Maryland in a number of tests. An additional P-61A-10NO, AAF Serial Number 42-39395, was subjected by the Navy to a series of test catapult launches in an attempt to qualify the aircraft for shipboard launches, but the Black Widow was never flown from an aircraft carrier. These aircraft did not receive the naval designation F2T-1, but continued on as P-61s.

Shortly after the war, the Navy also borrowed two P-61Cs (AAF Ser. No. 43-8336 and AAF Ser. No. 43-8347) from the USAAF and used them for air-launches of the experimental Martin PTV-N-2U Gorgon IV ramjet-powered missile, the first launch taking place on 14 November 1947. While carrying a Gorgon under each wing, the P-61C would go into a slight dive during launch to reach the speed necessary for the ramjet to start. These two naval Black Widows were returned to the USAF in 1948, and transferred to storage shortly afterwards.

During the war, the Army Air Corps/Army Air Forces tried to fly P-61s off of an aircraft carrier along the California coast in an attempt to mimic the success of the Doolittle Raid's B-25 Mitchells. However, after those tests proved unsuccessful and with the ongoing Manhattan Project fulfilling its potential, this project was discontinued.

Retirement

In 1945, the USAAF programmed a jet night interceptor to replace the P-61. To meet the jet-powered night fighter requirement, Curtiss-Wright proposed an aircraft of a similar configuration, but adapted specifically for the interception role. The company designation of Model 29A was assigned to the project. The Army ordered two prototypes under the designation Curtiss-Wright XF-87 Blackhawk and the name "Blackhawk" was assigned. However, the USAAF also thought highly of the Northrop proposal, which was given the designation N-24 by the company. Two prototypes were ordered under the designation XP-89 in December 1946.

Development delays in both the XF-89 and XF-87 projects meant that the P-61 Black Widows still in service in 1947 were rapidly reaching the end of their operational lifetimes. They had been built for wartime duty, and at most, had been expected to be in service only for a year or two until being replaced by jets. No plans for long-term use had been made, and a parts shortage meant that those aircraft still in service by late 1947 were being supported by cannibalization of stored aircraft at Davis-Monthan AFB and other storage depots. In early 1948, the USAF ordered that a flyoff take place between the Northrop XF-89, the Curtiss XF-87, and the Navy's Douglas XF3D-1 Skyknight. The evaluation team judged the XF-89 as being the superior fighter and having the best development potential, and the F-87A order was cancelled in its entirety on 10 October. The F-89s finally reached USAF service in 1951.[26]

An interim replacement was found with the F-82 Twin Mustang, whose engineless airframes were sitting in storage at North American Aviation in California and could be put into service quickly. Retirement of the P-61 began in 1948 by F-82s equipped as night fighters, and by the end of the year all of the ADC Black Widows in the United States, Alaska and in Panama were off the inventory rolls. Most of Far East Air Force's P-61s were retired in 1949; the last operational Black Widow of the 68th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter Group left Japan in May 1950, missing the Korean War by only a month.[24]

In 1948, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) obtained a P-61C from Air Research and Development Command for a series of drop tests of swept-wing aerodynamic drones at Moffett Field, California. Much engineering data was obtained from these tests. An RP-61C, AF Ser. No. 45-59300, thus became the last operational USAF P-61 to be retired at the end of the NACA testing in 1953. A second P-61C (AF Ser. No. 43-8330) which was still flyable was obtained from the Smithsonian Institution by NACA in October 1950 for these tests, and remained in use by NACA until 9 August 1954, being the last P-61 in government use. This aircraft is now on public display at the NASM's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.[23] P-61B-15NO, AF Ser. No. 42-39754, was used by NACA's Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio for tests of airfoil-type ramjets. P-61C-1NO, AF Ser. No. 43-8357, was used at Ames as a source for spare parts for other P-61 and RP-61 aircraft.

Civilian use

Surviving aircraft were offered to civilian governmental agencies, or declared surplus and offered for sale on the commercial market. Five were eventually issued civil registrations

P-61B-1NO, AAF Ser. No. 42-39419, had been bailed to Northrop during most of its military career, who then bought the aircraft from the government at the end of the war. Having the civilian registration number NX30020 assigned to it, it was used as an executive transport, as a flight-test chase plane, and for tests with advanced navigational equipment. Later it was purchased by the Jack Ammann Photogrammetric Engineers, a photo-mapping company based in Texas; then in 1963, it was sold to an aerial tanker company and used for fighting forest fires. However, it crashed while fighting a fire on 23 August 1963, killing its pilot. In 2016 restoration work on a surviving P-61 is making progress with the wings ready to be attached next. [27]

Last flight

The last flying example of the P-61 line was a rare F-15A Reporter (RF-61C) (AF Ser. No. 45-59300), the first production model Reporter to be built. The aircraft was completed on 15 May 1946, and served with the USAAF and later the U.S. Air Force until 6 February 1948, when it was reassigned to the Ames Aeronautical Laboratory at Moffett Field in California, where it was reconfigured to serve as a launch vehicle for air dropped scale models of experimental aircraft. It served in this capacity until 1953, when it was replaced by a mammoth wind tunnel used for the same testing. In April 1955, the F-15 was declared surplus along with a "spare parts" F-61C (AF Ser. No. 43-8357).

The F-15 was sold, along with the parts P-61, to Steward-Davis, Incorporated of Gardena, California, and given the civilian registration N5093V. Unable to sell this P-61C, Steward-Davis scrapped it in 1957. Steward-Davis made several modifications to the Reporter to make it suitable for aerial survey work, including switching to a canopy taken from a Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star, and to propellers taken from an older P-61. The aircraft was sold in September 1956 to Compañía Mexicana Aerofoto, S. A. of Mexico City and assigned the Mexican registration XB-FUJ. In Mexico, the Reporter was used for aerial survey work, the very role for which it was originally designed. It was later bought by Aero Enterprises Inc. of Willets, California and returned to the USA in January 1964 carrying the civilian registration number N9768Z. The fuselage tank and turbosupercharger intercoolers were removed and the aircraft was fitted with a 1,600 gal (6,056 l) chemical tank for fire-fighting. It was purchased by Cal-Nat of Fresno, California at the end of 1964, which operated it as a firefighting aircraft for the next 3 1⁄2 years. In March 1968, the F-15 was purchased by TBM, Inc., an aerial firefighting company located in Tulare, California (the company's name representing the TBM Avenger, their primary equipment), who performed additional modifications on the aircraft to improve its performance, including experimenting with several types of propellers before deciding on Curtiss Electric type 34 propellers taken from a late model Lockheed Constellation.[6]

On 6 September 1968, Ralph Ponte, one of three civilian pilots to hold a rating for the F-15, was flying a series of routine Phos-Chek drops on a fire raging near Hollister, California. In an effort to reduce his return time, Ponte opted to reload at a small airfield nearer the fire. The runway was shorter than the one in Fresno, and despite a reduced load, hot air from the nearby fire reduced the surrounding air pressure and rendered the aircraft overweight. Even at full power the Reporter had not rotated after clearing the 3,500 ft (1,067 m) marker, and Ponte quickly decided to abort his takeoff. Despite every effort to control the hurtling craft, the Reporter careened off the runway and through a vegetable patch, before striking an embankment which tore off the landing gear. The aircraft then slid sideways, broke up and caught fire. Ponte scrambled through the shattered canopy unhurt, while a firefighting Avenger dropped its load of Phos-Chek on the plane's two engines, possibly saving Ponte's life. The F-15, though intact, was deemed too badly damaged to rebuild, and was soon scrapped, bringing an end to the career of one of Northrop's most successful designs.[6]

Variants

| Designation | Changes from previous model |

|---|---|

| XP-61 | The first two prototypes. |

| YP-61 | Pre-production series; 13 built. |

| P-61A-1 | First production version, R-2800-10 engines producing 2,000 hp (1,491 kW); 45 built, the last seven without the turret. |

| P-61A-5 | No turret, R-2800-65 engines producing 2,250 hp (1,678 kW); 35 built. |

| P-61A-10 | Water injection to increase duration of maximum power output; 100 built. |

| P-61A-11 | One hardpoint under each wing for bombs or fuel tanks; 20 built. |

| P-61B-1 | Nose stretched 8 in (20 cm), SCR-695 tail warning radar; 62 built. |

| P-61B-2 | Reinstated underwing hardpoints as on P-61A-11; 38 built. |

| P-61B-10 | Four underwing hardpoints; 46 built. |

| P-61B-11 | Reinstated turret with two 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns; five built. |

| P-61B-15 | Turret with four 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns; 153 built as largest production run of any P-61 version. |

| P-61B-16 | Turret armament reduced to two machine guns; six built. |

| P-61B-20 | New General Electric turret with four machine guns; 84 built. |

| P-61B-25 | Turret automatically aimed and fired by the APG-1 gun-laying radar connected to an analogue computer; six built. |

| P-61C | Turbosupercharged (General Electric CH-5-A3) [28] R-2800-73 engines producing 2,800 hp (2,088 kW), top speed increased to 430 mph (374 kn, 692 km/h) at 30,000 ft (9,145 m). However, the aircraft suffered from longitudinal instability at weights above 35,000 lb (15,875 kg) and from excessive takeoff runs—up to 3 mi (5 km) at a 40,000 lb (18,143 kg) takeoff weight; 41 built, 476 more cancelled after the end of the war. |

| TP-61C | P-61Cs converted to dual-control training aircraft. |

| XP-61D | One P-61A-5 (number 42-5559) and one P-61A-10 (number 42-5587) fitted with GE CH-5-A3 turbosupercharged R-2800-14 engines; cancelled when P-61C entered production. |

| XP-61E | Two P-61B-10s (numbers 42-39549 and 42-39557) converted to daytime long-range escort fighters. Tandem crew sat under a blown canopy which replaced the turret, additional fuel tanks were installed in place of the radar operator's cockpit in the rear of the fuselage pod, and four 0.50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns took place of the radar in the nose (the 20 mm/.79 in ventral cannon were retained as well). First flight 20 November 1944, cancelled after the war ended. The first prototype was converted to an XF-15, the second lost in take-off accident 11 April 1945.[29] |

| XP-61F | Abandoned conversion of one P-61C to XP-61E standard. |

| P-61G | Sixteen P-61B converted for meteorological research. |

| F-15A Reporter | Photoreconnaissance variant with a new center pod with pilot and camera operator seated in tandem under a single bubble canopy, and six cameras taking place of radar in the nose. Powered by the same turbosupercharged R-2800-73 engines as the P-61C. The first prototype XF-15 was converted from the first XP-61E prototype, the second XF-15A was converted from a P-61C (number 43-8335). The aircraft had a takeoff weight of 32,145 lb (14,580 kg) and a top speed of 440 mph (382 kn, 708 km/h). Only 36 of the 175 ordered F-15As were built before the end of the war. After formation of the United States Air Force in 1947, F-15A was redesignated RF-61C. F-15As were responsible for most of the aerial maps of North Korea used at the start of the Korean War.[30] |

| F2T-1N | Twelve USAAF P-61B's transferred to the United States Marine Corps. |

All models and variants of the P-61 were produced at Northrop's Hawthorne, California manufacturing plant.[31]

Operators

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States Army Air Forces night fighter squadrons. |

Pacific Theater

- 418th Night Fighter Squadron (April 1943–February 1947). Deployed to Southwest Pacific, November 1943; received P-61s in September 1944 at Hollandia Airfield, NEI. Operated in Netherlands East Indies, Philippines, Okinawa. Inactivated on Okinawa. After inactivation personnel, equipment and aircraft assigned to 4th Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 421st Night Fighter Squadron (May 1943–February 1947). Deployed to Southwest Pacific, January 1944; received P-61s in June 1944 at Nadzab Airfield, PNG. Operated in Papua New Guinea, Netherlands East Indies, Philippines, Okinawa. Inactivated in Japan. After inactivation personnel, equipment and aircraft assigned to 68th Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 547th Night Fighter Squadron (March 1944–February 1946). Deployed to Southwest Pacific, September 1944; received P-61s in October 1944 at Owi Airfield, NEI. Operated in Netherlands East Indies, Philippines, Okinawa. Inactivated in Japan.

- 6th Night Fighter Squadron (Formerly 6th Pursuit Squadron) (January 1943–February 1947). Received P-61s in May 1944 at John Rogers Field, Hawaii Territory. Deployed to Mariana Islands, Central Pacific June 1944-May 1945. Inactivated in Japan. After inactivation, personnel, equipment and aircraft assigned to 339th Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 548th Night Fighter Squadron (April 1944–December 1945). Received P-61s in September 1944 at Hickam Field, Hawaii Territory. Deployed to Central Pacific, December 1944. Operated in Saipan, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. Inactivated on Okinawa.

- 549th Night Fighter Squadron (May 1944–February 1946). Received P-61s in October 1944 at Kipapa Gulch Airfield, Hawaii Territory. Deployed to Central Pacific, February 1945. Operated in Saipan, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. Inactivated on Guam.

- 419th Night Fighter Squadron (April 1943–February 1947). Deployed to South Pacific, February 1943; received P-61s in May 1944 at Buka Airfield, Bougainville, Solomon Islands. Operated in Solomon Islands, Admiralty Islands, Netherlands East Indies, New Guinea, Philippines. Inactivated in Philippines.

- 550th Night Fighter Squadron (June 1944–January 1946). Deployed to South Pacific, December 1944; received P-61s in January 1945 at Middleburg Airfield, NEI. Operated in Netherlands East Indies, Philippines. Inactivated in Philippines.

European Theater

- 422d Night Fighter Squadron (August 1943–September 1945). Deployed to ETO, March 1944; received P-61s in May 1944 at RAF Scorton, England. Operated in England, France, Belgium, Germany. Inactivated in France.

- 425th Night Fighter Squadron (December 1943–August 1947). Deployed to ETO, March 1944; received P-61s in June 1944 at RAF Scorton, England. Operated in England, France, Germany. Inactivated in France.

- 414th Night Fighter Squadron (January 1943–September 1947). Deployed to MTO, May 1943; received P-61s in December 1944 at Pontedera Airfield, Italy. Operated in Algeria, Sardinia, Corsica, Italy, plus detachment to Belgium. Reassigned to Shaw AAF, South Carolina, 15 August 1946 and inactivated 16 March 1947. Personnel and aircraft were reassigned to the 319th Fighter Squadron (All Weather) and flown to Rio Hato AB, Panama.

- 415th Night Fighter Squadron (February 1943–September 1947). Deployed to MTO, May 1943; received P-61s in May 1945 at Braunshardt Airfield (Y-72), Germany. Operated in Algeria, Italy, Corsica, France, Germany. Reassigned to Shaw AAF, South Carolina, 13 July 1946 and reassigned to Alaskan Air Command, 19 May 1947. Inactivated on 1 September 1947, personnel and aircraft assigned to Alaskan Air Command 449th Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 416th Night Fighter Squadron (February 1943–November 1946). Deployed to ETO, May 1943; MTO, August 1943. Received P-61s in September 1944 at Rosignano Airfield, Italy. Operated in Italy, Corsica, France, Germany. Inactivated 9 November 1946 and personnel, equipment and aircraft assigned to 2d Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 417th Night Fighter Squadron (February 1943–November 1946). Deployed to ETO, May 1943; MTO, August 1943. Received P-61s in September 1944 at Borgo Airfield, Corsica. Operated in England, Algeria, Tunisia, Corsica, France, Germany. Inactivated 9 November 1946 and personnel, equipment and aircraft assigned to 5th Fighter Squadron (All Weather).

- 427th Night Fighter Squadron (February 1944-October 1945). Deployed to MTO, August 1944; received P-61s in August 1944 at Payne Airfield, Egypt. Was designated for assignment to Poltava Airfield, Ukraine on the Eastern Front, for night defense of USAAF airfields as part of the Operation Frantic shuttle bombing missions. When the Soviets did not allow USAAF night fighters to defend the Ukraine bomber bases, the squadron flew some missions from Pomigliano Airfield, Italy, then was reassigned to Tenth Air Force in China-Burma-India Theater.

China-Burma-India Theatre

- 426th Night Fighter Squadron (January 1944–November 1945). Deployed to CBI, June 1944; received P-61s in September 1944 at Madhaiganj Airfield, India. Operated briefly from India (10th AF), but moved to China (14th AF) in October where it operated until September 1945. Inactivated in India October 1945.

- 427th Night Fighter Squadron (February 1944–October 1945). Reassigned to CBI from Twelfth Air Force in Italy in October 1944; equipped with P-61s. Flights of aircraft operated from widely dispersed airfields in India and Burma (10th AF), and China (14th AF). Squadron consolidated in India and inactivated, September 1945.

Training Units

- Formed on 1 July 1943 at Orlando Army Air Base, Florida from elements of the Army Air Force School of Applied Tactics (AAFSAT) Fighter Command School 50th Pursuit Group.

- Reassigned to IV Fighter Command, Hammer Army Airfield, California, 1 January 1944.

- Disbanded 31 March 1944, replaced by 450th Army Air Forces Base Unit under Fourth Air Force 319th Wing.

- School inactivated on 31 August 1945.[33][34]

- Training Squadrons:

- 348th Night Fighter Squadron (OTU)

- 349th Night Fighter Squadron (OTU)

- 420th Night Fighter Squadron (RTU)

- 424th Night Fighter Squadron (RTU)[35]

Postwar P-61 squadrons

Note: The P-61 (Pursuit) designation of the Black Widow was changed to F-61 (Fighter) on 11 June 1948.

- 2d Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 416th Night Fighter Squadron in November 1946 at AAF Station Schweinfurt, Germany.

- Assigned to 52d Fighter Group at Mitchel Army Airfield, New York in June 1947. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustangs at McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey in October 1949.

- 5th Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 417th Night Fighter Squadron in November 1946 at AAF Station Schweinfurt, Germany

- Assigned to 52d Fighter Group at Mitchel Army Airfield, New York in June 1947. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustang at McGuire Air Force Base, New Jersey in October 1949.

- 317th Fighter Squadron. Assigned to 325th Fighter Group at Mitchel Army Airfield, New York in May 1947 and assigned P-61s. Reassigned to Hamilton Army Airfield, California in November 1947. Reassigned to Moses Lake Air Force Base, Washington in November 1948 where it transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustangs.

- 318th Fighter Squadron. Assigned to 325th Fighter Group at Mitchel Army Airfield, New York in May 1947 and assigned P-61s. Reassigned to Hamilton Army Airfield, California in December 1947. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustangs in May 1948.

- 319th Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 414th Night Fighter Squadron. Ground echelon of unit formed at Rio Hato Army Air Base, Panama in March 1947; air echelon acquired P-61 aircraft at Shaw Field, South Carolina and flew them to Panama for air defense of the Panama Canal. Assigned to 6th Fighter Wing. Squadron was subsequently reassigned to France Air Force Base, Panama Canal Zone in January 1948. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustangs in December 1948.

- 449th Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 415th Night Fighter Squadron at Adak Army Air Field, Aleutian Islands, Alaska on 1 September 1947. Later transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustang in December 1948.

- 4th Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 418th Night Fighter Squadron in August 1948 at Naha Air Base, Okinawa. Assigned to 347th Fighter Group. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustang in September 1948.

- 68th Fighter Squadron. Formed from equipment and personnel of 421st Night Fighter Squadron in August 1948 at Bofu Air Base, Japan. Assigned to 347th Fighter Group. Transitioned to F-82 Twin Mustangs in February 1950.

- 339th Fighter Squadron. Formed from personnel and equipment of 6th Night Fighter Squadron in February 1947 at Johnson Air Base Japan. Assigned to 347th Fighter Group. F-82 Twin Mustangs assigned in February 1950. Note: The 339th was the last USAF squadron equipped with F-61s, the last aircraft being sent to reclamation at Tachikawa Air Base, Japan in May 1950.

- 8th Photographic Reconnaissance Squadron. Flew F-15A (RF-61C) Reporter (1947–1949) from Johnson Air Base, Japan. Aircraft reassigned to 82d Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron until inactivated on 1 April 1949

- 57th Reconnaissance Squadron and 58th Reconnaissance Squadron. Performed Weather Reconnaissance training at Rapid City Army Air Base, South Dakota (July 1945–January 1946).

Survivors

Four P-61s are known to survive today.

- P-61B-1NO c/n 964 AAF Ser. No. 42-39445, is under restoration to flying status by the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania.[36][37] The aircraft crashed on 10 January 1945 on Mount Cyclops, Papua New Guinea and was recovered in 1989 by the Mid-Atlantic Air Museum of Reading, Pennsylvania. The aircraft has been undergoing a slow restoration since then with the intention of eventually returning it to flying condition, with the civilian registration N550NF. When finished, it is expected to be over 70% new construction. By May 2011, 80% of the restoration had been completed, with only the installation of the wings and engines remaining. As of June 2014, the engines (although not yet in running condition) were installed, as were the engine cowlings and cooling flaps. However, MAAM has only one usable propeller, and is attempting to raise funds for a second unit.

- P-61B-15NO c/n 1234 AAF Ser. No. 42-39715 is on static display inside the Beijing Air and Space Museum (BASM) at Beihang University (BUAA) in Beijing, China.[38][39] This aircraft was manufactured by Northrop Aircraft, Hawthorne CA and accepted by the USAAF on 5 Feb 1945. It was sent to Newark, NJ for deployment 16 Feb 1945 and departed the US 26 Feb 1945. It was then assigned to the Tenth Air Force, China Burma India Theater of Operations, 427th NFS 3 March 1945. At the end of the war the Communist Chinese came to one of the forward airfields in Sichuan Province and ordered the Americans out, but instructed to leave their aircraft. It has been reported that there had been three P-61s taken and sometime later the Chinese wrecked two of them. P-61B-15NO c/n 1234 was stricken by the USAAF 31 December 1945.[40] P-61B-15NO c/n 1234 was turned over to the Chengdu Institute of Aeronautical Engineering in 1947. When the Institute moved to its present location, it did not take this aircraft with them, instead shipping it to BUAA (then called Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics) in 1954 and placed on outside display with other aircraft as part of a museum. Sometime in 2008–2009 the museum closed and the display aircraft were moved to a parking lot approximately 200 metres south. The outer wing sections of P-61B-15NO c/n 1234 were removed during this transfer. It was confirmed in September 2012 that the museum's display aircraft were no longer at the parking lot. By April 2013 the P-61 had been reassembled and repainted in the new BASM building with the other aircraft that were previously outside.

- P-61C-1NO c/n 1376 AF Ser. No. 43-8330, is on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum in Chantilly, Virginia.[41] The aircraft was delivered to the Army on 28 July 1945. By 18 October, this P-61 was flying at Ladd Field, in Alaska conducting cold weather tests, where it remained until 30 March 1946. The airplane was later moved to Pinecastle AAF in Florida for participation in the National Thunderstorm Project. Pinecastle AAF personnel removed the guns and turret from 43-8330 in July 1946 to make room for new equipment. In September the aircraft moved to Clinton County Army Air Base in Ohio, where it remained until January 1948. The Air Force then reassigned the aircraft to the Flight Test Division at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. After being declared surplus in 1950 it was donated by the U.S. Air Force to the National Air Museum in Washington, D.C. (which became the National Air and Space Museum in 1966).

- On 3 October 1950, the P-61C was transferred to Park Ridge, Illinois where it was stored along with other important aircraft destined for eventual display at the museum. The aircraft was moved temporarily to the museum's storage facility at Chicago's O'Hare International Airport, but before the museum could arrange to ferry the aircraft to Washington, D.C. the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics asked to borrow it. In a letter to museum director Paul E. Garber dated 30 November 1950, NACA director for research I.H. Abbott described his agency's "urgent" need for the P-61 to use as a high-altitude research craft. Garber agreed to an indefinite loan of the aircraft, and the Black Widow arrived at the Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, at Naval Air Station Moffett Field in California, on 14 February 1951. When NACA returned the aircraft to the Smithsonian in 1954 it had accumulated only 530 total flight hours. From 1951 to 1954 the Black Widow was flown on roughly 50 flights as a mothership, dropping recoverable swept-wing test bodies as part of a National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics program to test swept-wing aerodynamics. NACA test pilot Donovan Heinle made the aircraft's last flight when he ferried it from Moffett Field to Andrews Air Force Base, arriving on 10 August 1954. The aircraft was stored there for seven years before Smithsonian personnel trucked it to the museum's Garber storage facility in Suitland, Maryland. In January 2006 the P-61C was moved into Building 10 so that Garber's 19 restoration specialists, three conservationists and three shop volunteers could work exclusively on the aircraft for its unveiling at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center on 8 June. The aircraft was restored to its configuration as a flight test aircraft for swept-wing aeronautics, so the armament and turret were not replaced. A group of former P-61 air crews were present at the aircraft's unveiling, including former Northrop test pilot John Myers.[42]

- P-61C-1NO c/n 1399 AAF Ser. No. 43-8353 is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, Ohio.[43] It is marked as P-61B-1NO 42-39468 and painted to represent "Moonlight Serenade" of the 550th Night Fighter Squadron. The aircraft was presented to the Boy Scouts of America following World War II and kept at Grimes Field in Urbana, Ohio. On June 20, 1958 it was returned to the museum by the Tecumseh Chapter of the Boy Scouts of America in Springfield, Ohio. The aircraft recently had a reproduction turret installed, which was fabricated by the Museum's restoration team.

Specifications (P-61B-20-NO)

Data from Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II,[44] and Northrop P-61 Black Widow.[45]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2–3 (pilot, radar operator, optional gunner)

- Length: 49 ft 7 in (15.11 m)

- Wingspan: 66 ft 0 in (20.12 m)

- Height: 14 ft 8 in (4.47 m)

- Wing area: 662.36 ft2 (61.53 m2)

- Empty weight: 23,450 lb (10,637 kg)

- Loaded weight: 29,700 lb (13,471 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 36,200 lb (16,420 kg)

- Fuel capacity:

- Internal: 640 gal (2,423 L) of AN-F-48 100/130-octane rating gasoline

- External: Up to four 165 gal (625 L) or 310 gal (1,173 L) tanks under the wings

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney R-2800-65W Double Wasp radial engines, 2,250 hp (1,680 kW) each

- Propellers: four-bladed Curtiss Electric propeller, 1 per engine

- Propeller diameter: 146 in (3.72 m)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 366 mph (318 kn, 589 km/h) at 20,000 ft (6,095 m)

- Combat range: 610 mi (520 nmi, 982 km)

- Ferry range: 1,900 mi (1,650 nmi, 3,060 km) with four external fuel tanks

- Service ceiling: 33,100 ft (10,600 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,540 ft/min (12.9 m/s)

- Wing loading: 45 lb/ft2 (219 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.15 hp/lb (250 W/kg)

- Time to altitude: 12 min to 20,000 ft (6,100 m) (1,667 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns:

- 4 × 20 mm (.79 in) Hispano AN/M2 cannon in ventral fuselage, 200 rounds per gun

- 4 × .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine guns in remotely operated, full-traverse upper turret, 560 rpg

- Bombs: for ground attack, four bombs of up to 1,600 lb (726 kg) each or six 5 in (127 mm) HVAR unguided rockets could be carried under the wings. Some aircraft could also carry one 1,000 lb (454 kg) bomb under the fuselage.

Avionics

- SCR-720 (AI Mk.X) search radar

- SCR-695 tail warning radar

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Boulton Paul P.92

- Bristol Beaufighter

- de Havilland Mosquito

- Douglas P-70 Havoc

- Focke-Wulf Ta 154

- Gloster F.9/37

- Grumman F7F Tigercat

- Heinkel He 219

- Junkers Ju 88

- Kawasaki Ki-102

- Lockheed P-38M Night Lightning

- Lockheed XP-58 Chain Lightning

- Messerschmitt Bf 110

- Mitsubishi Ki-83

- Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Knaack, M.S. Post-World War II Fighters, 1945–1973. Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History, 1988. ISBN 0-16-002147-2.

- ↑ Wilson 1998, p. 142.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 93, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp. 93–7, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- 1 2 3 Pape 1991

- 1 2 3 Johnson 1976, pp. 30–44.

- ↑ Davis and Menard 1990, p. 4.

- ↑ Thompson 1999, p. 86.

- ↑ Thompson 1999, p. 88.

- ↑ "Corky Meyer's Flight Journal", Corwin H. Meyer, Specialty Press 2006, ISBN 1-58007-093-0, p.127

- ↑ http://naca.central.cranfield.ac.uk/reports/1947/naca-report-868.pdf Fig.64 and 65

- ↑ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 97, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ↑ Mason 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Thompson 1971, pp. 44–50.

- ↑ Sharp and Bowyer 1997, p. 379.

- ↑ "The United States Army Air Forces in World War II - Developing a True Night Fighter". usaaf.net. Archived from the original on January 26, 2004. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Beale, Nick. "Ghost Bombers, the Moonlight War of NSG 9." ghostbombers.com, November 2004. Retrieved: 19 July 2010.

- ↑ "Night Fighter List", USAF Historical Study No. 85 (1978), USAF Credits for the Destruction of Enemy Aircraft, World War II, Office of Air Force History, pp. 673–680.

- 1 2 Pape and Harrison 1982

- ↑ van Ness, Gordon, ed. The One Voice of James Dickey: His Letters and Life, 1970–1997. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8262-1572-7.

- 1 2 Thompson 1999

- ↑ Thompson 1999, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pape 1992, p. 102.

- 1 2 Pape 1992, p. 103.

- ↑ Thompson 1999, p. 89.

- ↑ Baugher, Joe. "Northrop XP-89 Scorpion." USAF Fighters, 6 November 1999. Retrieved: 13 September 2010.

- ↑ http://www.jetwhine.com/2016/05/wings-next-maams-black-widow/

- ↑ GE Turbocharger Manual "Section XIX" for its CH-5 series turbochargers, pgs. 206-209

- ↑ Pape and Harrison 1976, pp. 10–24.

- ↑ Thompson 1999, pp. 84–85. Note: "Their photos of Korea were invaluable to the UN forces during the first few weeks of that war. It was not until the Marine photo version of the F7F Tigercat made its sweeps over Inchon that any additional pictures were taken."

- ↑ Dean, Francis H. America's Hundred Thousand: U.S. Production Fighters of World War II. Atglen, PA: Schiffer, 2000. ISBN 0-7643-0072-5.

- ↑ P-61 units virgin-widow.com

- ↑ Northrop P-61 Black Widow—The Complete History and Combat Record, Garry R. Pape, John M. Campbell and Donna Campbell, Motorbooks International, 1991.

- ↑ McFarland, Stephen L. (1988), Conquering the Night Army Air Forces Night Fighters at War, Air Force History and Museums Program, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

- ↑ Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1982) [1969]. Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II (reprint ed.). Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 0-405-12194-6. LCCN 70605402. OCLC 72556.

- ↑ "P-61B Black Widow/42-39445" maam.org. Retrieved: 19 July 2010.

- ↑ "FAA Registry: N550NF" FAA.gov Retrieved: 12 April 2012.