Pāli Canon

| Part of a series on |

| Theravāda Buddhism |

|---|

|

The Pāli Canon (Pali: Tipitaka, Sanskrit: IAST: Tripiṭaka) is the standard collection of scriptures in the Theravadan Buddhist tradition, as preserved in the Pāli language.[1] It is the first known and most complete extant early Buddhist canon.[2][3]

It was composed in North India and was preserved orally until it was committed to writing during the Fourth Buddhist Council in Sri Lanka in 29 BCE, approximately 454 years after the death of Gautama Buddha.[lower-alpha 1] It was composed by members of Sangha of each ancient major Buddhist sub-tradition. It is written in Pali, Sanskrit, and regional Asian languages.[5] It survives in various versions. The surviving Sri Lankan version is the most complete.[6]

The Pāli Canon falls into three general categories, called pitaka (from Pali piṭaka, meaning "basket", referring to the receptacles in which the palm-leaf manuscripts were kept).[7] Because of this, the canon is traditionally known as the Tipiṭaka (Sanskrit: IAST: Tripiṭaka; "three baskets"). The three pitakas are as follows:

- Vinaya Pitaka ("Discipline Basket"), dealing with rules or discipline of the sangha;[7][6]

- Sutta Pitaka (Sutra/Sayings Basket), discourses and sermons of Buddha, some religious poetry and is the largest basket;[7]

- Abhidhamma Pitaka, treatises that elaborate Buddhist doctrines, particularly about mind, also called the "systematic philosophy" basket, likely composed starting about and after 300 BCE.[7][8]

The Vinaya Pitaka and the Sutta Pitaka are remarkably similar to the works of other early Buddhist schools. The Abhidhamma Pitaka, however, is a strictly Theravada collection and has little in common with the Abhidhamma works recognized by other Buddhist schools.[9]

The Canon in the tradition

The Canon is traditionally described by the Theravada as the Word of the Buddha (buddhavacana), though this is obviously not intended in a literal sense, since it includes teachings by disciples.[10]

The traditional Theravādin (Mahavihārin) interpretation of the Pali Canon is given in a series of commentaries covering nearly the whole Canon, compiled by Buddhaghosa (fl. 4th–5th century CE) and later monks, mainly on the basis of earlier materials now lost. Subcommentaries have been written afterward, commenting further on the Canon and its commentaries. The traditional Theravādin interpretation is summarized in Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga.[11]

An official view is given by a spokesman for the Buddha Sasana Council of Burma:[12] the Canon contains everything needed to show the path to nirvāna; the commentaries and subcommentaries sometimes include much speculative matter, but are faithful to its teachings and often give very illuminating illustrations. In Sri Lanka and Thailand, "official" Buddhism has in large part adopted the interpretations of Western scholars.[13]

Although the Canon has existed in written form for two millennia, its earlier oral nature has not been forgotten in actual Buddhist practice within the tradition: memorization and recitation remain common. Among frequently recited texts are the Paritta. Even lay people usually know at least a few short texts by heart and recite them regularly; this is considered a form of meditation, at least if one understands the meaning. Monks are of course expected to know quite a bit more (see Dhammapada below for an example). A Burmese monk named Vicittasara even learned the entire Canon by heart for the Sixth Council (again according to the usual Theravada numbering).[14][15]

The relation of the scriptures to Buddhism as it actually exists among ordinary monks and lay people is, as with other major religious traditions, problematic: the evidence suggests that only parts of the Canon ever enjoyed wide currency, and that non-canonical works were sometimes very much more widely used; the details varied from place to place.[16] Rupert Gethin suggests that the whole of Buddhist history may be regarded as a working out of the implications of the early scriptures.[17]

Origins

According to a late part of the Pali Canon, the Buddha taught the three pitakas.[18] It is traditionally believed by Theravadins that most of the Pali Canon originated from the Buddha and his immediate disciples. According to the scriptures, a council was held shortly after the Buddha's passing to collect and preserve his teachings. The Theravada tradition states that it was recited orally from the 5th century BCE to the first century BCE, when it was written down.[19] The memorization was enforced by regular communal recitations. The tradition holds that only a few later additions were made. The Theravādin pitakas were first written down in Sri Lanka in the Alu Viharaya Temple no earlier than 29-17 B.C.E.[20]

Much of the material in the Canon is not specifically Theravādin, but is instead the collection of teachings that this school preserved from the early, non-sectarian body of teachings. According to Peter Harvey, it contains material which is at odds with later Theravādin orthodoxy. He states that "the Theravādins, then, may have added texts to the Canon for some time, but they do not appear to have tampered with what they already had from an earlier period."[21] A variety of factors suggest that the early Sri Lankan Buddhists regarded canonical literature as such and transmitted it conservatively.[22]

Authorship

Authorship according to Theravadins

Prayudh Payutto argues that the Pali Canon represents the teachings of the Buddha essentially unchanged apart from minor modifications. He argues that it also incorporates teachings that precede the Buddha, and that the later teachings were memorized by the Buddha's followers while he was still alive. His thesis is based on study of the processes of the first great council, and the methods for memorization used by the monks, which started during the Buddha's lifetime. It's also based on the capability of a few monks, to this day, to memorize the entire canon.[23]

Bhikkhu Sujato and Bhikkhu Brahmali argue that it is likely that much of the Pali Canon dates back to the time period of the Buddha. They base this on many lines of evidence including the technology described in the canon (apart from the obviously later texts), which matches the technology of his day which was in rapid development, that it doesn't include back written prophecies of the great Buddhist ruler King Ashoka (which Mahayana texts often do) suggesting that it predates his time, that in its descriptions of the political geography it presents India at the time of Buddha, which changed soon after his death, that it has no mention of places in South India, which would have been well known to Indians not long after Buddha's death and various other lines of evidence dating the material back to his time.[24]

Authorship according to academic scholars

The views of scholars concerning the authorship of the Pali Canon can be grouped into three categories:

- Attribution to the Buddha himself and his early followers

- Attribution to the period of pre-sectarian Buddhism

- Agnosticism

Scholars have both supported and opposed the various existing views.

Views concerning authorship of the Buddha himself

Several scholars of early Buddhism argue that the nucleus of the Buddhist teachings in the Pali Canon may derive from Gautama Buddha himself, but that part of it also was developed after the Buddha by his early followers. Richard Gombrich says that the main preachings of the Buddha (as in the Vinaya and Sutta Pitaka) are coherent and cogent, and must be the work of a single person: the Buddha himself, not a committee of followers after his death.[lower-alpha 2][26]

Other scholars are more cautious, and attribute part of the Pali canon to the Buddha's early followers. Peter Harvey[27] also states that "much" of the Pali Canon must derive from the Buddha's teaching, but also states that "parts of the Pali Canon clearly originated after the time of the Buddha."[lower-alpha 3] A.K. Warder has stated that there is no evidence to suggest that the shared teaching of the early schools was formulated by anyone else than the Buddha and his immediate followers.[lower-alpha 4] J.W. de Jong has said it would be "hypocritical" to assert that we can say nothing about the teachings of earliest Buddhism, arguing that "the basic ideas of Buddhism found in the canonical writings could very well have been proclaimed by him [the Buddha], transmitted and developed by his disciples and, finally, codified in fixed formulas."[29] Alex Wynne has said that some texts in the Pali Canon may go back to the very beginning of Buddhism, which perhaps include the substance of the Buddha's teaching, and in some cases, maybe even his words.[lower-alpha 5]. He suggests that the canon was composed early on soon after Buddha's paranirvana, but after a period of free improvisation, and then the core teachings were preserved nearly verbatim by memory.[30] Hajime Nakamura writes that while nothing can be definitively attributed to Gautama as a historical figure, some sayings or phrases must derive from him.[31]

Views concerning authorship in the period of pre-sectarian Buddhism

| History of literature by era |

|---|

| Bronze Age |

| Classical |

| Early Medieval |

| Medieval |

| Early Modern |

| Modern by century |

|

|

Most scholars do agree that there was a rough body of sacred literature that a relatively early community maintained and transmitted.[32][lower-alpha 6]

Much of the Pali Canon is found also in the scriptures of other early schools of Buddhism, parts of whose versions are preserved, mainly in Chinese. Many scholars have argued that this shared material can be attributed to the period of Pre-sectarian Buddhism. This is the period before the early schools separated in about the fourth or third century BCE.

Views concerning agnosticism

Some scholars see the Pali Canon as expanding and changing from an unknown nucleus.[33] Arguments given for an agnostic attitude include that the evidence for the Buddha's teachings dates from (long) after his death.

Some scholars of later Indian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism say that little or nothing goes back to the Buddha. Ronald Davidson[34] has little confidence that much, if any, of surviving Buddhist scripture is actually the word of the historical Buddha.[32] Geoffrey Samuel[35] says the Pali Canon largely derives from the work of Buddhaghosa and his colleagues in the 5th century AD.[36] Gregory Schopen argues[37] that it is not until the 5th to 6th centuries CE that we can know anything definite about the contents of the Canon. This position was criticized by A. Wynne.[4]

The earliest books of the Pali Canon

Different positions have been taken on what are the earliest books of the Canon. The majority of Western scholars consider the earliest identifiable stratum to be mainly prose works,[38] the Vinaya (excluding the Parivāra)[39] and the first four nikāyas of the Sutta Pitaka,[40][41] and perhaps also some short verse works[42] such as the Suttanipata.[39] However, some scholars, particularly in Japan, maintain that the Suttanipāta is the earliest of all Buddhist scriptures, followed by the Itivuttaka and Udāna.[43] However, some of the developments in teachings may only reflect changes in teaching that the Buddha himself adopted, during the 45 years that the Buddha was teaching.[lower-alpha 7]

Most of the above scholars would probably agree that their early books include some later additions.[44] On the other hand, some scholars have claimed[45][46][47][48] that central aspects of late works are or may be much earlier.

One of the edicts of Ashoka, the 'Calcutta-Bairat edict', lists several works from the canon which he considers advantageous. According to Alexander Wynne:

The general consensus seems to be that what Asoka calls Munigatha correspond to the Munisutta (Sn 207-21), Moneyasute is probably the second half of the Nalakasutta (Sn 699-723), and Upatisapasine may correspond to the Sariputtasutta (Sn 955-975). The identification of most of the other titles is less certain, but Schmithausen, following Oldenberg before him, identifies what Asoka calls the Laghulovada with part of a prose text in the Majjhima Nikaya, the Ambalatthika-Rahulovada Sutta (M no.61).[49]

This seems to be evidence which indicates that some of these texts were already fixed by the time of the reign of Ashoka (304–232 BCE), which means that some of the texts carried by the Buddhist missionaries at this time might also have been fixed.[49]

According to the Sri Lankan Mahavamsa, the Pali Canon was written down in the reign of King Vattagāmini (Vaṭṭagāmiṇi) (1st century BCE) in Sri Lanka, at the Fourth Buddhist council. Most scholars hold that little if anything was added to the Canon after this,[50][51][52] though Schopen questions this.

Texts

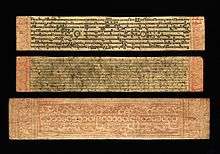

Manuscripts

The climate of Theravāda countries is not conducive to the survival of manuscripts. Apart from brief quotations in inscriptions and a two-page fragment from the eighth or ninth century found in Nepal, the oldest manuscripts known are from late in the fifteenth century,[53] and there is not very much from before the eighteenth.[54]

Printed editions and digitized editions

The first complete printed edition of the Canon was published in Burma in 1900, in 38 volumes.[55] The following editions of the Pali text of the Canon are readily available in the West:

- Pali Text Society edition, 1877–1927 (a few volumes subsequently replaced by new editions), 57 volumes including indexes.[54]

- The Pali scriptures and some Pali commentaries were digitized as an MS-DOS/extended ASCII compatible database through cooperation between the Dhammakaya Foundation and the Pali Text Society in 1996 as PALITEXT version 1.0: CD-ROM Database of the Entire Buddhist Pali Canon ISBN 978-974-8235-87-5.[56]

- Thai edition, 1925–28, 45 volumes; more accurate than the PTS edition, but with fewer variant readings;[57]

- Sixth Council edition, Rangoon, 1954–56, 40 volumes; more accurate than the Thai edition, but with fewer variant readings;[60]

- electronic transcript by Vipāssana Research Institute available online[61] in searchable database free of charge, or on CD-ROM (p&p only) from the institute.[62]

- Another transcript of this edition, produced under the patronage of the Supreme Patriarch of Thailand, World Tipitaka Edition, 2005, 40 volumes, published by the Dhamma Society Fund,[63] claims to include the full extent of changes made at the Sixth Council, and therefore reflect the results of the council more accurately than some existing Sixth Council editions. Available for viewing online (registration required) at Tipiṭaka Quotation WebService.[64]

- Sinhalese (Buddha Jayanti) edition, 1957–?1993, 58 volumes including parallel Sinhalese translations, searchable, free of charge (not yet fully proofread.) Available at Journal of Buddhist Ethics.[65]

- Sinhalese (Buddha Jayanti). Image files in Sinhala script. The only accurate version of the Sri Lankan text available, in individual page images. Cannot be searched though.[66]

- Transcript in BudhgayaNews Pali Canon.[67] In this version it is easy to search for individual words across all 16,000+ pages at once and view the contexts in which they appear.

No one edition has all the best readings, and scholars must compare different editions.[68]

- The Complete Collection of Chinese Pattra Scripture[69]

Translations

Pali Canon in English Translation, 1895-, in progress, 43 volumes so far, Pali Text Society, Bristol; for details of these and other translations of individual books see the separate articles. In 1994, the then President of the Pali Text Society stated that most of these translations were unsatisfactory.[70] Another former President said in 2003 that most of the translations were done very badly.[25] The style of many translations from the Canon has been criticized[71] as "Buddhist Hybrid English", a term invented by Paul Griffiths for translations from Sanskrit. He describes it as "deplorable", "comprehensible only to the initiate, written by and for Buddhologists".[72]

Selections: see List of Pali Canon anthologies.

A translation by Bhikkhu Nanamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi of the Majjhima Nikaya was published by Wisdom Publications in 1995.

Translations by Bhikkhu Bodhi of the Samyutta Nikaya and the Anguttara Nikaya were published by Wisdom Publications in 2003 and 2012, respectively.

Contents of the Canon

| Pāli Canon |

|---|

| Vinaya Pitaka |

| Sutta Pitaka |

| Abhidhamma Pitaka |

As noted above, the Canon consists of three pitakas.

- Vinaya Pitaka (vinayapiṭaka)

- Sutta Pitaka or Suttanta Pitaka

- Abhidhamma Pitaka

Details are given below. For more complete information, see standard references on Pali literature.[73][74]

Vinaya Pitaka

The first category, the Vinaya Pitaka, is mostly concerned with the rules of the sangha, both monks and nuns. The rules are preceded by stories telling how the Buddha came to lay them down, and followed by explanations and analysis. According to the stories, the rules were devised on an ad hoc basis as the Buddha encountered various behavioral problems or disputes among his followers. This pitaka can be divided into three parts:

- Suttavibhanga (-vibhaṅga) Commentary on the Patimokkha, a basic code of rules for monks and nuns that is not as such included in the Canon. The monks' rules are dealt with first, followed by those of the nuns' rules not already covered.

- Khandhaka Other rules grouped by topic in 22 chapters.

- Parivara (parivāra) Analysis of the rules from various points of view.

Sutta Pitaka

The second category is the Sutta Pitaka (literally "basket of threads", or of "the well spoken"; Sanskrit: Sutra Pitaka, following the former meaning) which consists primarily of accounts of the Buddha's teachings. The Sutta Pitaka has five subdivisions, or nikayas:

- Digha Nikaya (dīghanikāya) 34 long discourses.[75] Joy Manné argues[76] that this book was particularly intended to make converts, with its high proportion of debates and devotional material.

- Majjhima Nikaya 152 medium-length discourses.[75] Manné argues[76] that this book was particularly intended to give a solid grounding in the teaching to converts, with a high proportion of sermons and consultations.

- Samyutta Nikaya (saṃyutta-) Thousands of short discourses in fifty-odd groups by subject, person etc. Bhikkhu Bodhi, in his translation, says this nikaya has the most detailed explanations of doctrine.

- Anguttara Nikaya (aṅguttara-) Thousands of short discourses arranged numerically from ones to elevens. It contains more elementary teaching for ordinary people than the preceding three.

- Khuddaka Nikaya A miscellaneous collection of works in prose or verse.

Abhidhamma Pitaka

The third category, the Abhidhamma Pitaka (literally "beyond the dhamma", "higher dhamma" or "special dhamma", Sanskrit: Abhidharma Pitaka), is a collection of texts which give a scholastic explanation of Buddhist doctrines particularly about mind, and sometimes referred to as the "systematic philosophy" basket.[7][8] There are seven books in the Abhidhamma Pitaka:

- Dhammasangani (-saṅgaṇi or -saṅgaṇī) Enumeration, definition and classification of dhammas

- Vibhanga (vibhaṅga) Analysis of 18 topics by various methods, including those of the Dhammasangani

- Dhatukatha (dhātukathā) Deals with interrelations between ideas from the previous two books

- Puggalapannatti (-paññatti) Explanations of types of person, arranged numerically in lists from ones to tens

- Kathavatthu (kathā-) Over 200 debates on points of doctrine

- Yamaka Applies to 10 topics a procedure involving converse questions (e.g. Is X Y? Is Y X?)

- Patthana (paṭṭhāna) Analysis of 24 types of condition[77]

The traditional position is that abhidhamma refers to the absolute teaching, while the suttas are adapted to the hearer. Most scholars describe the abhidhamma as an attempt to systematize the teachings of the suttas:[77][78] Cousins says that where the suttas think in terms of sequences or processes the abhidhamma thinks in terms of specific events or occasions.[79]

Use of Brahmanical devices

The Pali Canon uses many Brahmanical terminology and concepts. For example, in Samyutta Nikaya 111, Majjhima Nikaya 92 and Vinaya i 246 of the Pali Canon, the Buddha praises the Agnihotra as the foremost sacrifice and the Gayatri mantra as the foremost meter:

aggihuttamukhā yaññā sāvittī chandaso mukham.Sacrifices have the agnihotra as foremost; of meter the foremost is the Sāvitrī.[80]

Comparison with other Buddhist canons

The other two main Buddhist canons in use in the present day are the Chinese Buddhist Canon and the Tibetan Kangyur.

The standard modern edition of the Chinese Buddhist Canon is the Taishō Revised Tripiṭaka, with a hundred major divisions, totaling over 80,000 pages. This includes Vinayas for the Dharmaguptaka, Sarvāstivāda, Mahīśāsaka, and Mahāsaṃghika schools. It also includes the four major Āgamas, which are analogous to the Nikayas of the Pali Canon. Namely, they are the Saṃyukta Āgama, Madhyama Āgama, Dīrgha Āgama, and Ekottara Āgama. Also included are the Dhammapada, the Udāna, the Itivuttaka, and Milindapanha. There are also additional texts, including early histories, that are preserved from the early Buddhist schools but not found in Pali. The canon contains voluminous works of Abhidharma, especially from the Sarvāstivāda school. The Indian works preserved in the Chinese Canon were translated from Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit, Classical Sanskrit, or from regional Prakrits. The Chinese generally referred to these simply as "Sanskrit" (Ch. 梵語, Fànyǔ). The first woodblock printing of the whole Chinese Buddhist Canon was done by imperial order in China in CE 868.[81]

The Tibetan Kangyur comprises about a hundred volumes and includes versions of the Vinaya Pitaka, the Dhammapada (under the title Udanavarga) and parts of some other books. Due to the later compilation, it contains comparatively fewer early Buddhist texts than the Pali and Chinese canons.

The Chinese and Tibetan canons are not translations of the Pali and differ from it to varying extents, but contain some recognizably similar early works. However, the Abhidharma books are fundamentally different works from the Pali Abhidhamma Pitaka. The Chinese and Tibetan canons also consist of Mahāyāna sūtras and Vajrayāna tantras, which have few parallels in the Pali Canon.[lower-alpha 8]

See also

- Atthakatha, Pali commentaries on the Pali Canon

- Buddhist texts

- Chinese Buddhist canon

- Tibetan Buddhist canon

- Sanskrit Buddhist literature

- Karl Eugen Neumann

- Pali Literature

- Palm-leaf manuscript

- Paracanonical texts (Theravada Buddhism)

- Theravada Buddhism

- Tripitaka

- Tripitaka Koreana

Notes

- ↑ If the language of the Pāli canon is north Indian in origin, and without substantial Sinhalese additions, it is likely that the canon was composed somewhere in north India before its introduction to Sri Lanka.[4]

- ↑ "I am saying that there was a person called the Buddha, that the preachings probably go back to him individually... that we can learn more about what he meant, and that he was saying some very precise things."[25]

- ↑ "While parts of the Pali Canon clearly originated after the time of the Buddha, much must derive from his teaching."[2]

- ↑ "there is no evidence to suggest that it was formulated by anyone else than the Buddha and his immediate followers." [28]

- ↑ "If some of the material is so old, it might be possible to establish what texts go back to the very beginning of Buddhism, texts which perhaps include the substance of the Buddha's teaching, and in some cases, maybe even his words", [4]

- ↑ Ronald Davidson states, "most scholars agree that there was a rough body of sacred literature (disputed) that a relatively early community (disputed) maintained and transmitted."[32]

- ↑ "as the Buddha taught for 45 years, some signs of development in teachings may only reflect changes during this period."[2]

- ↑ Most notably, a version of the Atanatiya Sutta (from the Digha Nikaya) is included in the tantra (Mikkyo, rgyud) divisions of the Taisho and of the Cone, Derge, Lhasa, Lithang, Narthang and Peking (Qianlong) editions of the Kangyur.[82]

References

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Harvey 1990, p. 3.

- ↑ Maguire 2001, p. 69–.

- 1 2 3 Wynne 2003.

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 4, Quote: Pali literature is quite extensive, but very little of it is what we would call secular. So far as we know, it has all been composed by the members of the Sangha..

- 1 2 Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 924. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gombrich 2006, p. 4.

- 1 2 Damien Keown (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 2008.

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 153-4.

- ↑ Morgan 1956, p. 71.

- ↑ McDaniel 2006, p. 302.

- ↑ Mendelson 1975, p. 266.

- ↑ Brown 2006.

- ↑ Manné 1990, p. 103f.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 43.

- ↑ Book of the Discipline, volume VI, page 123

- ↑ Norman 2005, p. 75-76.

- ↑ Schopen, Gregory; Lopez Jr., Donald S. (1997). Bones, Stones, And Buddhist Monks: Collected Papers On The Archaeology, Epigraphy, And Texts Of Monastic Buddhism In India. University of Hawaii Press. p. 27. ISBN 0824817486.

- ↑ Harvey 1995, p. 9.

- ↑ Wynne 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ Payutto, P. A. "The Pali Canon What a Buddhist Must Know" (PDF).

- ↑ Bhikkhu Sujato and Bhikkhu Brahmali. "The Authenticity of the Early Buddhist Texts" (PDF). Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies.

- 1 2 Gombrich (b).

- ↑ Gombrich 2006, p. 20f.

- ↑ Peter Harvey

- ↑ Warder 1999, p. inside flap.

- ↑ De Jong 1993, p. 25.

- ↑ Wynne, Alex. "The Oral Transmission of Early Buddhist Literature - Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (Volume 27. No. 1 2004)".

- ↑ Nakamura 1999, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Davidson 2003, p. 147.

- ↑ Buswell 2004, p. 10.

- ↑ Ronald Davidson, academic profile Archived November 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ about Geoffrey Samuel

- ↑ Samuel 2012, p. 48.

- ↑ Schopen 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Warder 1963, p. viii.

- 1 2 Cousins 1984, p. 56.

- ↑ Bechert 1984, p. 78.

- ↑ Gethin 1992, p. 42f.

- ↑ Gethin 1992.

- ↑ Nakamura 1999, p. 27.

- ↑ Ñāṇamoli 1982, p. xxix.

- ↑ Cousins & 1982/3.

- ↑ Harvey, page 83

- ↑ Gethin 1992, p. 48.

- ↑ The Guide, Pali Text Society, page xxvii

- 1 2 Wynne 2004.

- ↑ Ñāṇamoli 1982, p. xxxixf.

- ↑ Gethin 1992, p. 8.

- ↑ Harvey, page 3

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 "Pali Text Society Home Page". Palitext.com. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Grönbold 1984, p. 12 (as noted there and elsewhere, the 1893 Siamese edition was incomplete).

- ↑ Allon 1997, pp. 109–29.

- ↑ Warder 1963, pp. 382.

- ↑ "BUDSIR for Thai Translation". Budsir.org. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ "BUDSIR for Thai Translation". Budsir.mahidol.ac.th. Retrieved 2012-10-15.

- ↑ Hamm 1973.

- ↑ "The Pali Tipitaka". Tipitaka.org. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ "Vipassana Research Institute". Vri.dhamma.org. 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ "Society worldtipitaka". Dhammasociety.org. 2007-08-29. Archived from the original on 2007-03-17. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Tipiṭaka Studies

- ↑ Sri Lanka Tripitaka Project

- ↑ "Sri Lankan Pāḷi Texts". Retrieved 2013-01-15.

- ↑ "Pali Canon Online Database". BodhgayaNews. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Cone 2001.

- ↑ "《中国贝叶经全集》新闻发布会暨出版座谈会_华人佛教_凤凰网". Fo.ifeng.com. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Norman 1996, pp. 80.

- ↑ Journal of the Pali Text Society, Volume XXIX, page 102

- ↑ Griffiths 1981, pp. 17-32.

- ↑ Norman 1983.

- ↑ von Hinüber 2000, pp. 24-26.

- 1 2 Harvey, 1990 & appendix.

- 1 2 Manné 1990, pp. 29-88.

- 1 2 Harvey 1990, p. 83.

- ↑ Gethin 1998, p. 44.

- ↑ Cousins 1982, p. 7.

- ↑ Shults, Brett (May 2014). "On the Buddha's Use of Some Brahmanical Motifs in Pali Texts". Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies. 6: 119.

- ↑ Bechert 1984, p. 204.

- ↑ Skilling 1997, p. 84n, 553ff, 617ff..

Sources

- "《中国贝叶经全集》新闻发布会暨出版座谈会_华人佛教_凤凰网", Fo.ifeng.com, retrieved 2012-10-14

- Allon, Mark (1997), "An Assessment of the Dhammakaya CD-ROM: Palitext Version 1.0", Buddhist Studies (Bukkyō Kenkyū), 26: 109–29

- Bechert, Heinz; Gombrich, Richard F. (1984), The world of buddhism : buddhist monks and nuns in society and culture, London: Thames and Hudson

- Brown, E K; Anderson, Anne (2006), Encyclopedia of language &linguistics, Boston: Elsevier

- BUDSIR (Buddhist scriptures information retrieval) for Thai Translation, retrieved 2012-10-14

- Buswell, Robert E (2004), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, USA: Macmillan Reference

- Cone, Margaret (2001), Dictionary of Pali, vol. I, Oxford: Pali Text Society

- Cousins, L. S. (1984), In Richard Gombrich and K. R. Norman (ed.): Dhammapala, Buddhist studies in honour of Hammalava Saddhatissa, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka: University of Sri Jayawardenapura, p. 56

- Cousins, L. S. (1982), Pali oral literature. In Denwood and Piatigorski, eds.: Buddhist Studies, ancient and modern, London: Curzon Press, pp. 1–11

- Davidson, Ronald M. (2003), Indian Esoteric Buddhism, New York: Indian Esoteric BuddhismColumbia University Press, ISBN 0231126182

- De Jong, J.W. (1993), "The Beginnings of Buddhism", The Eastern Buddhist, 26 (2): 25

- Encyclopædia Britannica: ultimate reference suite (2008), Buddhism, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press

- Gethin, Rupert (1992), The Buddha's Path to Awakening, Leiden: E. J. Brill

- Gombrich (b), Richard, Interview by Kathleen Gregory, archived from the original on January 24, 2016, retrieved 2011 Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Gombrich, Richard F (2006), Theravada Buddhism (2nd ed.), London: Routledge

- Griffiths, Paul J. (1981), "Buddhist Hybrid English: Some Notes on Philology and Hermeneutics for Buddhologists", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 4 (2): 17–32

- Grönbold, Günter (1984), Der buddhistische Kanon: eine Bibliographie, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz

- Hamm (1973), In: Cultural Department of the German Embassy in India, ed., Varanasi: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, German Scholars on India, volume I

- Harvey, Peter (1995), The Selfless Mind., Surrey: Curzon Press

- Harvey, Peter (1990), Introduction to Buddhism, New York: Cambridge University Press

- Jones, Lindsay (2005), Councils, Buddhist. In: Encyclopedia of religion, Detroit: Macmillan Reference

- Maguire, Jack (2001), Essential Buddhism: A Complete Guide to Beliefs and Practices, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-04188-5

- Manné, Joy (1990), "Categories of sutta in the Pali Nikayas" (PDF), Journal of the Pali Text Society, XV: 29–88, archived from the original (PDF) on September 1, 2014

- McDaniel, Justin T. (2005), "The art of reading and teaching Dhammapadas: reform, texts, contexts in Thai Buddhist history", Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 28 (2): 299–336

- Mendelson, E. Michael (1975), Sangha and State in Burma, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press

- Morgan, Kenneth W. (1956), Path of the Buddha, New York: Ronald Press

- Nakamura, Hajime (1999), Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Ñāṇamoli, Bhikkhu;; Warder, Anthony Kennedy (1982), Introduction to Path of Discrimination, London: Pali Text Society: Distributed by Routledge and Kegan Paul

- Norman, K.R. (1983), Pali Literature, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz

- Norman, K.R. (1996), Collected Papers, volume VI, Bristol: Pali Text Society

- Norman, K. R. (2005). Buddhist Forum Volume V: Philological Approach to Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-135-75154-8.

- Pali Canon Online Database, Bodhgaya News, retrieved 2012-10-14

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2012), Introducing Tibetan Buddhism, New York: Routledge

- Schopen, Gregory (1997), Bones, Stones, and Buddhist Monks, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press

- Skilling, P.; ed. (1997). Mahasutras, volume I, Parts I & II. Oxford: Pali Text Society.

- Sri Lankan Pāḷi Texts, retrieved 2013-01-15

- "The Pali Tipitaka", Tipitaka.org, retrieved 2012-10-14

- "Vipassana Research Institute", Vri.dhamma.org, VRI Publications, retrieved 2012-10-14

- von Hinüber, Oskar (2000), A Handbook of Pāli Literature, Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-016738-2

- Warder, A. K. (1963), Introduction to Pali, London: Published for the Pali Text Society by Luzac

- Warder, Anthony Kennedy (2000), Indian Buddhism (3rd ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Wynne, Alexander (2003), How old is the Suttapiṭaka? The relative value of textual and epigraphical sources for the study of early Indian Buddhism (PDF), St John's College, archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2015

- Wynne, Alexander (2004). "The Oral Transmission of the Early Buddhist Literature". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 27 (1): 97–128.

- Wynne, Alexander (2007), The origin of Buddhist meditation, New York: Routledge

Further reading

- Hinüber, Oskar von (2000). A Handbook of Pāli Literature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016738-7.

- B. C. Law, History of Pali Literature, volume I, Trubner, London 1931

- Russell Webb (ed.), Analysis of the Pali Canon, The Wheel Publication No 217, Buddhist Publication Society, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 3rd ed. 2008.

- Ko Lay, U. (2003), Guide to Tipiṭaka, Selangor, Malaysia: Burma Piṭaka Association. Editorial Committee, Archived from the original on July 24, 2008

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pali Canon. |

- Sayadaw U Vicittasara Mingun Sayadaw: A Fabulous Memory

- Beginnings: The Pali Suttas by Samanera Bodhesako

English translations

- Access to Insight has many suttas translated into English

- Tipitaka Online of Nibbana.com. Burma (Myanmar)

- English translations by Bhikkhu Bodhi of selected suttas of the Majjhima Nikaya are made available by the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition at Wisdom Publications

- English translations by Bhikkhu Bodhi of selected suttas from the Anguttara Nikaya at Wisdom Publications

Pali Canon online

- Vipassana Research Institute (Based on 6th Council – Burmese version) (this site also offers a downloadable program which installs the entire Pali Tipitaka on your desktop for offline viewing)

- Sutta Central Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels (Multiple Languages)

- Thai Tripitaka (Thai version)

- Sinhala Tipitaka (Translated into Sinhala by a Government of Sri Lanka initiative)