Function (mathematics)

| Function | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x ↦ f (x) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| By domain and codomain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Classes/properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constant · Identity · Linear · Polynomial · Rational · Algebraic · Analytic · Smooth · Continuous · Measurable · Injective · Surjective · Bijective | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Constructions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Restriction · Composition · λ · Inverse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Generalizations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Partial · Multivalued · Implicit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

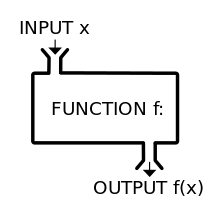

In mathematics, a function[1] is a relation between a set of inputs and a set of permissible outputs with the property that each input is related to exactly one output. An example is the function that relates each real number x to its square x2. The output of a function f corresponding to an input x is denoted by f(x) (read "f of x"). In this example, if the input is −3, then the output is 9, and we may write f(−3) = 9. Likewise, if the input is 3, then the output is also 9, and we may write f(3) = 9. (The same output may be produced by more than one input, but each input gives only one output.) The input variable(s) are sometimes referred to as the argument(s) of the function.

Functions of various kinds are "the central objects of investigation"[2] in most fields of modern mathematics. There are many ways to describe or represent a function. Some functions may be defined by a formula or algorithm that tells how to compute the output for a given input. Others are given by a picture, called the graph of the function. In science, functions are sometimes defined by a table that gives the outputs for selected inputs. A function could be described implicitly, for example as the inverse to another function or as a solution of a differential equation.

In modern mathematics,[3] a function is defined by its set of inputs, called the domain; a set containing the set of outputs, and possibly additional elements, as members, called its codomain (or target); and the set of all input-output pairs, called its graph. Sometimes the codomain is called the function's "range", but more commonly the word "range" is used to mean, instead, specifically the set of outputs (this is also called the image of the function). For example, we could define a function using the rule f(x) = x2 by saying that the domain and codomain are the real numbers, and that the graph consists of all pairs of real numbers (x, x2). The image of this function is the set of non-negative real numbers. Collections of functions with the same domain and the same codomain are called function spaces, the properties of which are studied in such mathematical disciplines as real analysis, complex analysis, and functional analysis.

In analogy with arithmetic, it is possible to define addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of functions, in those cases where the output is a number. Another important operation defined on functions is function composition, where the output from one function becomes the input to another function.

Introduction and examples

For an example of a function, let X be the set consisting of four shapes: a red triangle, a yellow rectangle, a green hexagon, and a red square; and let Y be the set consisting of five colors: red, blue, green, pink, and yellow. Linking each shape to its color is a function from X to Y: each shape is linked to a color (i.e., an element in Y), and each shape is "linked", or "mapped", to exactly one color. There is no shape that lacks a color and no shape that has more than one color. This function will be referred to as the "color-of-the-shape function".

The input to a function is called the argument and the output is called the value. The set of all permitted inputs to a given function is called the domain of the function, while the set of permissible outputs is called the codomain. Thus, the domain of the "color-of-the-shape function" is the set of the four shapes, and the codomain consists of the five colors. The concept of a function does not require that every possible output is the value of some argument, e.g. the color blue is not the color of any of the four shapes in X.

A second example of a function is the following: the domain is chosen to be the set of natural numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, ...), and the codomain is the set of integers (..., −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, ...). The function associates to any natural number n the number 4−n. For example, to 1 it associates 3 and to 10 it associates −6.

A third example of a function has the set of polygons as domain and the set of natural numbers as codomain. The function associates a polygon with its number of vertices. For example, a triangle is associated with the number 3, a square with the number 4, and so on.

The term range is sometimes used either for the codomain or for the set of all the actual values a function has.

Definition

In order to avoid the use of the informally defined concepts of "rules" and "associates", the above intuitive explanation of functions is completed with a formal definition. This definition relies on the notion of the Cartesian product. The Cartesian product of two sets X and Y is the set of all ordered pairs, written (x, y), where x is an element of X and y is an element of Y. The x and the y are called the components of the ordered pair. The Cartesian product of X and Y is denoted by X × Y.

A function f from X to Y is a subset of the Cartesian product X × Y subject to the following condition: every element of X is the first component of one and only one ordered pair in the subset.[4] In other words, for every x in X there is exactly one element y such that the ordered pair (x, y) is contained in the subset defining the function f. This formal definition is a precise rendition of the idea that to each x is associated an element y of Y, namely the uniquely specified element y with the property just mentioned.

Considering the "color-of-the-shape" function above, the set X is the domain consisting of the four shapes, while Y is the codomain consisting of five colors. There are twenty possible ordered pairs (four shapes times five colors), one of which is

- ("yellow rectangle", "red").

The "color-of-the-shape" function described above consists of the set of those ordered pairs,

- (shape, color)

where the color is the actual color of the given shape. Thus, the pair ("red triangle", "red") is in the function, but the pair ("yellow rectangle", "red") is not.

Notation

A function f is commonly declared by stating its domain X and codomain Y using the expression

or

In this context, the elements of X are called arguments of f. For each argument x, the corresponding unique y in the codomain is called the function value at x or the image of x under f. It is written as f(x). One says that f associates y with x or maps x to y. This is abbreviated by

A general function, to be defined for a particular context, is usually denoted by a single letter, most often the lower-case letters f, g, h. Special functions that have universally (or widely) recognized names and definitions most often have 2- to 4-letter symbols. These functions include, for instance, the trigonometric functions sine, cosine, and tangent with symbols sin, cos, tan (occasionally tg), the natural logarithm function, denoted by ln or loge, and the signum function, denoted by sgn. The value of the function f at a point x is denoted f(x), while the value of a function like sine at x can be notated as sin(x) or sin x, with the parentheses omitted if no ambiguity arises. Note that by convention, general functions are displayed using an italicized letter (like a variable), while special functions are set in roman type.

Although tending to pedantry when carefully observed on every occasion, one should distinguish between a function ("the machine") and its value at a particular point ("the output"): the symbol f represents the function, while f(x) is its value at x. Thus, it is sloppy and an abuse of notation to say: "Let f(x) be the function x2 + 1." A careful, precise statement should instead be "Let f : R → R be the function that maps x to the value x2 + 1," or "Let f: R → R be the function (defined by) " (see below for the usage of ). In practice, sloppy statements are made (either intentionally or unintentionally) in order to avoid cumbersome circumlocutions like these.

The distinction between a function and its value becomes important, for instance, when one wishes to talk about the duality between a function and its argument. In these situations, it is desirable to show the symmetry between function and argument and place the function and the argument on an equal footing. One way to do so is to use bracket notation: we write for the expression f(x).[5] As examples, we can combine the bracket notation with the dot notation (discussed below) in the expression to represent the mapping (an example of a functional) for a given, fixed , without having to introduce the letter f, which is merely a placeholder ("dummy"). Although this notation might allow for cleaner expression of abstract mappings, applying it toward functions containing rational or polynomial expressions is awkward and unwieldy. Thus, this notation is seldom used in general mathematical or scientific settings. (For a related notation used in quantum mechanics, see bra-ket notation.)

Practically speaking, the notation ("maps to", an arrow with a bar at its tail) is flexible and convenient. It can be used to briefly mention and define a function without assigning it a name. In other cases, to define a function in full, a mapping defined with a "maps to" arrow could be stacked, in parallel, immediately below the declaration of the function name, domain, and the codomain. For example,

The first part can be read as:

- "f is a function from ℕ (the set of natural numbers) to ℤ (the set of integers)" or

- "f is a ℤ-valued function of an ℕ-valued variable".

The second part is read:

- "x maps to 4 − x."

In other words, this function has the natural numbers as domain, the integers as codomain. Strictly speaking, a function is properly defined only when the domain and codomain are specified. Moreover, the function

(with different domain) is a different function, even though the formulas defining f and g agree. Similarly, a function with a different codomain is also a different function. Nevertheless, many authors do not specify the domain and codomain, especially if these are clear from context. So in this example many just write f(x) = 4 − x. Sometimes, the maximal possible domain within a larger set implied by context is implicitly understood: a formula such as may mean that the domain of f is the set of real numbers x where the square root is defined (in this case x ≤ 2 or x ≥ 3). However, in a different context, this expression might refer to a complex-valued function .

Finally, dot notation is occasionally used to specify a function by replacement of the variable of interest in an expression with a dot. For example, may stand for , and may stand for the integral function .

Specifying a function

A function can be defined by any mathematical condition relating each argument (input value) to the corresponding output value. If the domain is finite, a function f may be defined by simply tabulating all the arguments x and their corresponding function values f(x). More commonly, a function is defined by a formula, or (more generally) an algorithm — a recipe that tells how to compute the value of f(x) given any x in the domain.

There are many other ways of defining functions. Examples include piecewise definitions, induction or recursion, algebraic or analytic closure, limits, analytic continuation, infinite series, and as solutions to integral and differential equations. The lambda calculus provides a powerful and flexible syntax for defining and combining functions of several variables. In advanced mathematics, some functions exist because of an axiom, such as the Axiom of Choice.

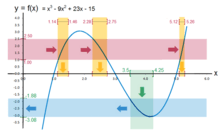

Graph

The graph of a function is its set of ordered pairs F. This is an abstraction of the idea of a graph as a picture showing the function plotted on a pair of coordinate axes; for example, (3, 9), the point above 3 on the horizontal axis and to the right of 9 on the vertical axis, lies on the graph of y = x2.

Formulas and algorithms

Different formulas or algorithms may describe the same function. For instance f(x) = (x + 1) (x − 1) is exactly the same function as f(x) = x2 − 1.[6] Furthermore, a function need not be described by a formula, expression, or algorithm, nor need it deal with numbers at all: the domain and codomain of a function may be arbitrary sets. One example of a function that acts on non-numeric inputs takes English words as inputs and returns the first letter of the input word as output.

As an example, the factorial function is defined on the nonnegative integers and produces a nonnegative integer. It is defined by the following inductive algorithm: 0! is defined to be 1, and n! is defined to be n(n − 1)! for all positive integers n. The factorial function is denoted with the exclamation mark (serving as the symbol of the function) after the variable (postfix notation).

Computability

Functions that send integers to integers, or finite strings to finite strings, can sometimes be defined by an algorithm, which gives a precise description of a set of steps for computing the output of the function from its input. Functions definable by an algorithm are called computable functions. For example, the Euclidean algorithm gives a precise process to compute the greatest common divisor of two positive integers. Many of the functions studied in the context of number theory are computable.

Fundamental results of computability theory show that there are functions that can be precisely defined but are not computable. Moreover, in the sense of cardinality, almost all functions from the integers to integers are not computable. The number of computable functions from integers to integers is countable, because the number of possible algorithms is. The number of all functions from integers to integers is higher: the same as the cardinality of the real numbers. Thus most functions from integers to integers are not computable. Specific examples of uncomputable functions are known, including the busy beaver function and functions related to the halting problem and other undecidable problems.

Basic properties

There are a number of general basic properties and notions. In this section, f is a function with domain X and codomain Y.

Image and preimage

If A is any subset of the domain X, then f(A) is the subset of the codomain Y consisting of all images of elements of A. We say the f(A) is the image of A under f. The image of f is given by f(X). On the other hand, the inverse image (or preimage, complete inverse image) of a subset B of the codomain Y under a function f is the subset of the domain X defined by

So, for example, the preimage of {4, 9} under the squaring function is the set {−3,−2,2,3}. The term range usually refers to the image,[7] but sometimes it refers to the codomain.

By definition of a function, the image of an element x of the domain is always a single element y of the codomain. However, the preimage of a singleton set (a set with exactly one element) may in general contain any number of elements. For example, if f(x) = 7 (the constant function taking value 7), then the preimage of {5} is the empty set but the preimage of {7} is the entire domain. It is customary to write f−1(b) instead of f−1({b}), i.e.

This set is sometimes called the fiber of b under f. (This notation is the same as that for the inverse function. However, the inverse function of a function is defined if and only if the function is one-to-one and onto. See below of the definition of these terms.)

Use of f(A) to denote the image of a subset A ⊆ X is consistent so long as no subset of the domain is also an element of the domain. In some fields (e.g., in set theory, where ordinals are also sets of ordinals) it is convenient or even necessary to distinguish the two concepts; the customary notation is f[A] for the set { f(x): x ∈ A }. Likewise, some authors use square brackets to avoid confusion between the inverse image and the inverse function. Thus they would write f−1[B] and f−1[b] for the preimage of a set and a singleton.

Injective and surjective functions

A function is called injective (or one-to-one; 1-1) if f(a) ≠ f(b) for any two elements a, b, a ≠ b of the domain. It is called surjective (or onto) if the range is identical to the codomain; that is, f(X) = Y. In other words, every element y in the codomain is mapped to by f from some x in the domain. Finally f is called bijective (or the function is a one-to-one correspondence) if it is both injective and surjective. A function that is injective, surjective, or bijective is referred to as an injection, a surjection, or a bijection, respectively. The existence of injections, surjections, or bijections between sets is the key concept defining the relative cardinalities (sizes) of the sets.

"One-to-one" and "onto" are terms that were more common in the older English language literature; "injective", "surjective", and "bijective" were originally coined as French words in the second quarter of the 20th century by the Bourbaki group and imported into English. As a word of caution, "a one-to-one function" is one that is injective, while a "one-to-one correspondence" refers to a bijective function. Also, the statement "f maps A onto B" differs from "f maps A into B" in that the former implies that f is an onto function (i.e., surjective), while the latter makes no assertion about the nature of the mapping. In more complicated statements the one letter difference can easily be missed. Due to the confusing nature of this older terminology, these terms have declined in popularity relative to the Bourbakian terms.

The above "color-of-the-shape" function is not injective, since two distinct shapes (the red triangle and the red rectangle) are assigned the same value. Moreover, it is not surjective, since the image of the function contains only three, but not all five colors in the codomain.

Function composition

The function composition of two functions takes the output of one function as the input of a second one. More specifically, the composition of f with a function g: Y → Z is the function defined by

That is, the value of x is obtained by first applying f to x to obtain y = f(x) and then applying g to y to obtain z = g(y). In the notation , the function on the right, f, acts first and the function on the left, g acts second, reversing English reading order. The notation can be memorized by reading the notation as "g of f" or "g after f". The composition is only defined when the codomain of f is the domain of g. Assuming that, the composition in the opposite order need not be defined. Even if it is, i.e., if the codomain of f is the codomain of g, it is not in general true that

That is, the order of the composition is important. For example, suppose f(x) = x2 and g(x) = x+1. Then g(f(x)) = x2+1, while f(g(x)) = (x+1)2, which is x2+2x+1, a different function.

A composite function g(f(x)) can be visualized as the combination of two "machines". The first takes input x and outputs f(x). The second takes as input the value f(x) and outputs g(f(x)).

A composite function g(f(x)) can be visualized as the combination of two "machines". The first takes input x and outputs f(x). The second takes as input the value f(x) and outputs g(f(x)). A concrete example of a function composition

A concrete example of a function composition Another composition. For example, we have here (g ∘ f )(c) = #.

Another composition. For example, we have here (g ∘ f )(c) = #.

Identity function

The unique function over a set X that maps each element to itself is called the identity function for X, and typically denoted by idX. Each set has its own identity function, so the subscript cannot be omitted unless the set can be inferred from context. Under composition, an identity function is "neutral": if f is any function from X to Y, then

Empty function

For any set A, there is exactly one function from the empty set to A, namely the empty function:

The graph of an empty function is a subset of the Cartesian product ∅ × A. Since the product is empty the only such subset is the empty set ∅. The empty subset is a valid graph since for every x in the domain ∅ there is a unique y in the codomain A such that (x, y) ∈ ∅ × A. This statement is an example of a vacuous truth since "there is no x in the domain."

The existence of an empty function from ∅ to ∅ is required to make the category of sets a category, because in a category, each object needs to have an "identity morphism", and only the empty function is the identity on the object ∅. The existence of a unique empty function from ∅ into each set A means that the empty set is an initial object in the category of sets. In terms of cardinal arithmetic, it means that k0 = 1 for every cardinal number k—particularly profound when k = 0 to illustrate the strong statement of indices pertaining to 0.

Restrictions and extensions

Informally, a restriction of a function f is the result of trimming its domain. More precisely, if S is any subset of X, the restriction of f to S is the function f|S from S to Y such that f|S(s) = f(s) for all s in S. If g is a restriction of f, then it is said that f is an extension of g.

The overriding of f: X → Y by g: W → Y (also called overriding union) is an extension of g denoted as (f ⊕ g): (X ∪ W) → Y. Its graph is the set-theoretical union of the graphs of g and f|X \ W. Thus, it relates any element of the domain of g to its image under g, and any other element of the domain of f to its image under f. Overriding is an associative operation; it has the empty function as an identity element. If f|X ∩ W and g|X ∩ W are pointwise equal (e.g., the domains of f and g are disjoint), then the union of f and g is defined and is equal to their overriding union. This definition agrees with the definition of union for binary relations.

Inverse function

An inverse function for f, denoted by f−1, is a function in the opposite direction, from Y to X, satisfying

That is, the two possible compositions of f and f−1 need to be the respective identity maps of X and Y.

As a simple example, if f converts a temperature in degrees Celsius C to degrees Fahrenheit F, the function converting degrees Fahrenheit to degrees Celsius would be a suitable f−1.

Such an inverse function exists if and only if f is bijective. In this case, f is called invertible. The notation (or, in some texts, just ) and f−1 are akin to multiplication and reciprocal notation. With this analogy, identity functions are like the multiplicative identity, 1, and inverse functions are like reciprocals (hence the notation).

Types of functions

Real-valued functions

A real-valued function f is one whose codomain is the set of real numbers or a subset thereof. If, in addition, the domain is also a subset of the reals, f is a real valued function of a real variable. The study of such functions is called real analysis.

Real-valued functions enjoy so-called pointwise operations. That is, given two functions

- f, g: X → Y

where Y is a subset of the reals (and X is an arbitrary set), their (pointwise) sum f+g and product f ⋅ g are functions with the same domain and codomain. They are defined by the formulas:

In a similar vein, complex analysis studies functions whose domain and codomain are both the set of complex numbers. In most situations, the domain and codomain are understood from context, and only the relationship between the input and output is given, but if , then in real variables the domain is limited to non-negative numbers.

The following table contains a few particularly important types of real-valued functions:

| Linear function | Quadratic function |

|---|---|

A linear function |  A quadratic function. |

| f(x) = ax + b. | f(x) = ax2 + bx + c. |

| Discontinuous function | Trigonometric functions |

The signum function is not continuous, since it "jumps" at 0. |

The sine and cosine functions. |

| Roughly speaking, a continuous function is one whose graph can be drawn without lifting the pen. | f(x) = sin(x) (red), f(x) = cos(x) (blue) |

Multivariate functions

A multivariate function is one which takes several inputs.

Further types of functions

There are many other special classes of functions that are important to particular branches of mathematics, or particular applications. Here is a partial list:

Function spaces

The set of all functions from a set X to a set Y is denoted by X → Y, by [X → Y], or by YX. The latter notation is motivated by the fact that, when X and Y are finite and of size |X| and |Y|, then the number of functions X → Y is |YX| = |Y||X|. This is an example of the convention from enumerative combinatorics that provides notations for sets based on their cardinalities. If X is infinite and there is more than one element in Y then there are uncountably many functions from X to Y, though only countably many of them can be expressed with a formula or algorithm.

Currying

An alternative approach to handling functions with multiple arguments is to transform them into a chain of functions that each takes a single argument. For instance, one can interpret Add(3,5) to mean "first produce a function that adds 3 to its argument, and then apply the 'Add 3' function to 5". This transformation is called currying: Add 3 is curry(Add) applied to 3. There is a bijection between the function spaces CA×B and (CB)A.

When working with curried functions it is customary to use prefix notation with function application considered left-associative, since juxtaposition of multiple arguments—as in (f x y)—naturally maps to evaluation of a curried function. Conversely, the → and ⟼ symbols are considered to be right-associative, so that curried functions may be defined by a notation such as f: ℤ → ℤ → ℤ = x ⟼ y ⟼ x·y.

Variants and generalizations

Alternative definition of a function

The above definition of "a function from X to Y" is generally agreed on, however there are two different ways a "function" is normally defined where the domain X and codomain Y are not explicitly or implicitly specified. Usually this is not a problem as the domain and codomain normally will be known. With one definition saying the function defined by f(x) = x2 on the reals does not completely specify a function as the codomain is not specified, and in the other it is a valid definition.

In the other definition a function is defined as a set of ordered pairs where each first element only occurs once. The domain is the set of all the first elements of a pair and there is no explicit codomain separate from the image.[8][9] Concepts like surjective have to be refined for such functions, more specifically by saying that a (given) function is surjective on a (given) set if its image equals that set. For example, we might say a function f is surjective on the set of real numbers.

If a function is defined as a set of ordered pairs with no specific codomain, then f: X → Y indicates that f is a function whose domain is X and whose image is a subset of Y. This is the case in the ISO standard.[7] Y may be referred to as the codomain but then any set including the image of f is a valid codomain of f. This is also referred to by saying that "f maps X into Y"[7] In some usages X and Y may subset the ordered pairs, e.g. the function f on the real numbers such that y=x2 when used as in f: [0,4] → [0,4] means the function defined only on the interval [0,2].[10] With the definition of a function as an ordered triple this would always be considered a partial function.

An alternative definition of the composite function g(f(x)) defines it for the set of all x in the domain of f such that f(x) is in the domain of g.[11] Thus the real square root of −x2 is a function only defined at 0 where it has the value 0.

Functions are commonly defined as a type of relation. A relation from X to Y is a set of ordered pairs (x, y) with x ∈ X and y ∈ Y. A function from X to Y can be described as a relation from X to Y that is left-total and right-unique. However, when X and Y are not specified there is a disagreement about the definition of a relation that parallels that for functions. Normally a relation is just defined as a set of ordered pairs and a correspondence is defined as a triple (X, Y, F), however the distinction between the two is often blurred or a relation is never referred to without specifying the two sets. The definition of a function as a triple defines a function as a type of correspondence, whereas the definition of a function as a set of ordered pairs defines a function as a type of relation.

Many operations in set theory, such as the power set, have the class of all sets as their domain, and therefore, although they are informally described as functions, they do not fit the set-theoretical definition outlined above, because a class is not necessarily a set. However some definitions of relations and functions define them as classes of pairs rather than sets of pairs and therefore do include the power set as a function.[12]

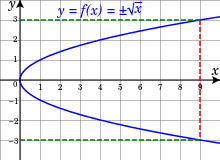

Partial and multi-valued functions

In some parts of mathematics, including recursion theory and functional analysis, it is convenient to study partial functions in which some values of the domain have no association in the graph; i.e., single-valued relations. For example, the function f such that f(x) = 1/x does not define a value for x = 0, since division by zero is not defined. Hence f is only a partial function from the real line to the real line. The term total function can be used to stress the fact that every element of the domain does appear as the first element of an ordered pair in the graph.

In other parts of mathematics, non-single-valued relations are similarly conflated with functions: these are called multivalued functions, with the corresponding term single-valued function for ordinary functions.

Functions with multiple inputs and outputs

The concept of function can be extended to an object that takes a combination of two (or more) argument values to a single result. This intuitive concept is formalized by a function whose domain is the Cartesian product of two or more sets.

For example, consider the function that associates two integers to their product: f(x, y) = x·y. This function can be defined formally as having domain ℤ×ℤ, the set of all integer pairs; codomain ℤ; and, for graph, the set of all pairs ((x, y), x·y). Note that the first component of any such pair is itself a pair (of integers), while the second component is a single integer.

The function value of the pair (x, y) is f((x, y)). However, it is customary to drop one set of parentheses and consider f(x, y) a function of two variables, x and y. Functions of two variables may be plotted on the three-dimensional Cartesian as ordered triples of the form (x, y, f(x, y)).

The concept can still further be extended by considering a function that also produces output that is expressed as several variables. For example, consider the integer divide function, with domain ℤ×ℕ and codomain ℤ×ℕ. The resultant (quotient, remainder) pair is a single value in the codomain seen as a Cartesian product.

Binary operations

The familiar binary operations of arithmetic, addition and multiplication, can be viewed as functions from ℝ×ℝ to ℝ. This view is generalized in abstract algebra, where n-ary functions are used to model the operations of arbitrary algebraic structures. For example, an abstract group is defined as a set X and a function f from X×X to X that satisfies certain properties.

Traditionally, addition and multiplication are written in the infix notation: x+y and x×y instead of +(x, y) and ×(x, y).

Functors

The idea of structure-preserving functions, or homomorphisms, led to the abstract notion of morphism, the key concept of category theory. In fact, functions f: X → Y are the morphisms in the category of sets, including the empty set: if the domain X is the empty set, then the subset of X × Y describing the function is necessarily empty, too. However, this is still a well-defined function. Such a function is called an empty function. In particular, the identity function of the empty set is defined, a requirement for sets to form a category.

The concept of categorification is an attempt to replace set-theoretic notions by category-theoretic ones. In particular, according to this idea, sets are replaced by categories, while functions between sets are replaced by functors.[13]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The words map or mapping, transformation, correspondence, and operator are often used synonymously. Halmos 1970, p. 30.

- ↑ Spivak 2008, p. 39.

- ↑ MacLane, Saunders; Birkhoff, Garrett (1967). Algebra (First ed.). New York: Macmillan. pp. 1–13.

- ↑ Hamilton, A. G. Numbers, sets, and axioms: the apparatus of mathematics. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-521-24509-5.

- ↑ Halmos, Paul R. (1958). Finite-Dimensional Vector Spaces (PDF). New York: Van Nostrand Company. pp. 21–25. ISBN 0-387-90093-4.

- ↑ Hartley Rogers, Jr (1987). Theory of Recursive Functions and Effective Computation. MIT Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-262-68052-1.

- 1 2 3 Quantities and Units - Part 2: Mathematical signs and symbols to be used in the natural sciences and technology, page 15. ISO 80000-2 (ISO/IEC 2009-12-01)

- ↑ Apostol, Tom (1967). Calculus vol 1. John Wiley. p. 53. ISBN 0-471-00005-1.

- ↑ Heins, Maurice (1968). Complex function theory. Academic Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Bartle 1967, p. 13.

- ↑ Bartle 1967, p. 21.

- ↑ Tarski, Alfred; Givant, Steven (1987). A formalization of set theory without variables. American Mathematical Society. p. 3. ISBN 0-8218-1041-3.

- ↑ John C. Baez; James Dolan (1998). "Categorification". arXiv:math/9802029

.

.

References

- Bartle, Robert (1967). The Elements of Real Analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Bloch, Ethan D. (2011). Proofs and Fundamentals: A First Course in Abstract Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-7126-5.

- Halmos, Paul R. (1970). Naive Set Theory. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90092-6.

- Spivak, Michael (2008). Calculus (4th ed.). Publish or Perish. ISBN 978-0-914098-91-1.

Further reading

- Anton, Howard (1980). Calculus with Analytical Geometry. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-03248-9.

- Bartle, Robert G. (1976). The Elements of Real Analysis (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-05464-1.

- Dubinsky, Ed; Harel, Guershon (1992). The Concept of Function: Aspects of Epistemology and Pedagogy. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-081-8.

- Hammack, Richard (2009). "12. Functions" (PDF). Book of Proof. Virginia Commonwealth University. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Husch, Lawrence S. (2001). Visual Calculus. University of Tennessee. Retrieved 2007-09-27.

- Katz, Robert (1964). Axiomatic Analysis. D. C. Heath and Company.

- Kleiner, Israel (1989). Evolution of the Function Concept: A Brief Survey. The College Mathematics Journal. 20. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 282–300. JSTOR 2686848. doi:10.2307/2686848.

- Lützen, Jesper (2003). "Between rigor and applications: Developments in the concept of function in mathematical analysis". In Roy Porter, ed. The Cambridge History of Science: The modern physical and mathematical sciences. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521571995. An approachable and diverting historical presentation.

- Malik, M. A. (1980). Historical and pedagogical aspects of the definition of function. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology. 11. pp. 489–492. doi:10.1080/0020739800110404.

- Reichenbach, Hans (1947) Elements of Symbolic Logic, Dover Publishing Inc., New York NY, ISBN 0-486-24004-5.

- Ruthing, D. (1984). Some definitions of the concept of function from Bernoulli, Joh. to Bourbaki, N. Mathematical Intelligencer. 6. pp. 72–77.

- Thomas, George B.; Finney, Ross L. (1995). Calculus and Analytic Geometry (9th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-53174-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Functions. |

- Khan Academy: Functions, free online micro lectures

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], "Function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang. "Function". MathWorld.

- The Wolfram Functions Site gives formulae and visualizations of many mathematical functions.

- Shodor: Function Flyer, interactive Java applet for graphing and exploring functions.

- xFunctions, a Java applet for exploring functions graphically.

- Draw Function Graphs, online drawing program for mathematical functions.

- Functions from cut-the-knot.

- Function at ProvenMath.

- Comprehensive web-based function graphing & evaluation tool.

- Abstractmath.org articles on functions