Bat-eared fox

| Bat-eared fox[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Caniformia |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Otocyon Müller, 1835 |

| Species: | O. megalotis |

| Binomial name | |

| Otocyon megalotis (Desmarest, 1822) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

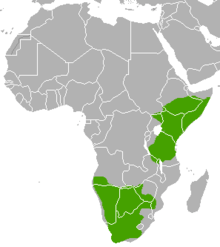

| Bat-eared fox range | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) is a species of fox found on the African savanna, named for its large ears,[4] which are used for thermoregulation.[3] Fossil records show this canid first appeared during the middle Pleistocene, about 800,000 years ago.[4] It is considered a basal canid species, resembling ancestral forms of the family.[5]

The bat-eared fox (also referred to as big-eared fox, black-eared fox, cape fox, and Delalande’s fox) has tawny fur with black ears, legs, and parts of the pointed face. It averages 55 cm in length (head and body), with ears 13 cm long. It is the only species in the genus Otocyon.[1] The name Otocyon is derived from the Greek words otus for ear and cyon for dog, while the specific name megalotis comes from the Greek words mega for large and otus for ear.[3]

Range and Distribution

Two allopatric populations (subspecies) occur in Africa. O. m. virgatus occurs from Ethiopia and southern Sudan to Tanzania. The other population, O. m. megalotis, occurs in the southern part of Africa. It ranges from southern Zambia and Angola to South Africa, and extends as far east as Mozambique and Zimbabwe, spreading into the Cape Peninsula and toward Cape Agulhas. Home ranges vary in size from 0.3 to 3.5 km2.[3]

Habitat

The bat-eared fox commonly occurs in short grasslands, as well as the more arid regions of the savanna. It prefers bare ground and areas where grass is kept short by grazing ungulates.[3] It tends to hunt in these short grass and low shrub habitats. However, it does venture into areas with tall grasses and thick shrubs to hide when threatened.[6]

In addition to raising their young in dens, bat-eared foxes use self-dug dens for shelter from extreme temperatures and winds. They also lie under acacia trees in South Africa to seek shade during the day.[3]

Diet

The bat-eared fox is predominantly an insectivore that uses its large ears to locate its prey. About 80–90% of their diet is harvester termites (Hodotermes mossambicus). When this particular species of termite is not available, they feed on other species of termites and have also been observed consuming other arthropods such as ants, beetles, crickets, grasshoppers, millipedes, moths, scorpions, spiders, and rarely birds, small mammals, reptiles, and fungi (the desert truffle Kalaharituber pfeilii[7]). The insects they eat fulfill the majority of their water intake needs. The bat-eared fox refuses to feed on snouted harvester termites, likely because it is not adapted to tolerate termites’ chemical defense.[3]

Dentition

The teeth of the bat-eared fox are much smaller and reduced in shearing surface formation than teeth of other canid species. This is an adaptation to its insectivorous diet.[8] Due to its unusual teeth, the bat-eared fox was once considered as a distinct subfamily of canids (Otocyoninae). However, according to more recent examinations, it is more closely related to the true foxes of the genus Vulpes. Other research places the genus as an outgroup which is not very closely related to foxes. The bat-eared fox is an old species that was widely distributed in the Pleistocene era. The teeth are not the bat-eared fox's only morphological adaptation for its diet. The lower jaw has a step-like protrusion called the subangular process, which anchors the large muscle to allow for rapid chewing. The digastric muscle is also modified to open and close the jaw five times per second.[3]

Foraging

Individuals usually hunt in groups, mostly in pairs and groups of three. Individuals forage as singles after family groups break in June or July and during the months after cub birth. Prey is located primarily by auditory means, rather than by smell or sight. Foraging patterns vary between seasons and coincide with termite availability. In the midsummer, individuals begin foraging at sunset, continuing throughout the night, and fading into the early morning; foraging is almost exclusively diurnal during the winter. Foraging usually occurs in patches, which match the clumped prey resources, such as termite colonies, that also occur in patches. Groups are able to forage on clumps of prey in patches because they do not fight each other for food due to their degree of sociality and lack of territoriality.[6]

Behavior

In the more northern areas of its range (around Serengeti), they are nocturnal 85% of the time. However, around South Africa, they are nocturnal only in the summer and diurnal during the winter.[9]

Bat-eared foxes are highly social animals. They often live in pairs or groups of up to 15 individuals, and home ranges of groups either overlap substantially or very little. Individuals forage, play, and rest together in a group, which helps in protection against predators. Social grooming occurs throughout the year, mostly between mature adults, but also between young adults and mature adults.[3]

Visual displays are very important in communication among bat-eared foxes. When they are looking intently at something, the head is held high, eyes are open, ears are erect and facing forward, and the mouth is closed. When an individual is in threat or showing submission, the ears are pulled back and lying against the head and the head is low. The tail also plays a role in communication. When an individual is asserting dominance or aggression, feeling threatened, playing, or being sexually aroused, the tail is arched in an inverted U shape. Individuals can also use piloerection, which occurs when individual hairs are standing straight, to make it appear larger when faced with extreme threat. When running, chasing, or fleeing, the tail is straight and horizontal. The bat-eared fox can recognize individuals up to 30 m away. The recognition process has three steps: First they ignore the individual, then they stare intently, and finally they either approach or attack without displays. When greeting another, the approaching individual shows symbolic submission which is received by the other individual with a high head and tail down. Few vocalizations are used for communication, but contact calls and warning calls are used, mostly during the winter. Glandular secretions and scratching, other than for digging, are absent in communication.[3]

Reproduction

The bat-eared fox is predominantly socially monogamous,[10] although it has been observed in polygynous groups. In contrast to other canids, the bat-eared fox has a reversal in parental roles, with the male taking on the majority of the parental care behavior. Females gestate for 60–70 days and give birth to litters consisting of one to six kits. Beyond lactation, which lasts 14 to 15 weeks,[3] males take over grooming, defending, huddling, chaperoning, and carrying the young between den sites. Additionally, male care and den attendance rates have been shown to have a direct correlation with cub survival rates.[11] The female forages for food, which she uses to maintain milk production, on which the pups heavily depend. Food foraged by the female is not brought back to the pups or regurgitated to feed the pups.[3]

Pups in the Kalahari region are born September–November and those in the Botswana region are born October–December. Young bat-eared foxes disperse and leave their family groups at 5–6 months old and reach sexual maturity at 8–9 months.[3]

Conservation threats

The bat-eared fox has some commercial use for humans. They are important for harvester termite population control, as the termites are considered pests. They have also been hunted for their fur by Botswana natives.[3] Additional threats to populations include disease and drought that can harm populations of prey; however, no major threats to bat-eared fox populations exist.[2]

References

| Wikispecies has information related to: Otocyon megalotis |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Otocyon megalotis. |

- 1 2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Nel, J.A.J. & Maas, B. (2008). "Otocyon megalotis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Clark, H. O. (2005). "Otocyon megalotis". Mammalian Species. 766: 1–5. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2005)766[0001:OM]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Paleobiology Database: Otocyon Basic info.

- ↑ Macdonald, David W.; Sillero-Zubir, Claudio (2004-06-24), The Biology and Conservation of Wild Canids, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780191523359, retrieved February 16, 2016

- 1 2 Kuntzsch, V.; Nel, J.A.J. (1992). "Diet of bat-eared foxes Otocyon megalotis in the Karoo". Koedoe. 35 (2): 37–48. doi:10.4102/koedoe.v35i2.403.

- ↑ Trappe JM, Claridge AW, Arora D, Smit WA (2008). "Desert truffles of the Kalahari: ecology, ethnomycology and taxonomy". Economic Botany. 62 (3): 521–529. doi:10.1007/s12231-008-9027-6.

- ↑ Kieser, J.A. (May 1995). "Gnathomandibular Morphology and Character Displacement in the Bat-eared Fox". Journal of Mammalogy. 76 (2): 542–550. JSTOR 1382362. doi:10.2307/1382362.

- ↑ Thompson, Paul. "Otocyon megalotis,bat-eared fox". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ Wright, Harry WY; et al. (2010). "Mating tactics and paternity in a socially monogamous canid, the bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis)". Journal of Mammalogy. 91 (2): 437–446. doi:10.1644/09-mamm-a-046.1.

- ↑ Wright, Harry William Yorkstone (2006). "Paternal den attendance is the best predictor of offspring survival in the socially monogamous bat-eared fox". Animal Behaviour. 71 (3): 503–510. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.03.043.