Spetsnaz

Spetsnaz (Russian: спецназ; IPA: [spʲɪt͜s'nas]), abbreviation for Войска специального назначения, tr. Voyska spetsialnogo naznacheniya pronounced [vɐjsˈka spʲɪt͡sɨˈalʲnəvə nəznɐˈt͜ɕenʲɪjə] (English: Special Purpose Forces or Special Purpose Military Units), is an umbrella term for special forces in Russian and is used in numerous post-Soviet states.

Historically, the term referred to special military units controlled by the military intelligence service GRU (Spetsnaz GRU). It also describes special purpose units, or task forces of other ministries (such as the Ministry of Internal Affairs ODON and Ministry of Emergency Situations' special rescue unit)[1] in post-Soviet countries.

As Spetsnaz is a Russian term, it is typically associated with the special forces units of Russia; but other post-Soviet states often refer to their special forces by the term as well since they inherited their special purpose units from the now-defunct Soviet security agencies. The 5th Spetsnaz Brigade of Belarus or the Alpha Group of the Security Service of Ukraine are both such examples of non-Russian Spetsnaz forces.[2]

Etymology

.jpg)

The Russian abbreviations spetsnaz and osnaz are syllabic abbreviations typical of Soviet era Russian, for spetsialnogo naznacheniya and osobogo naznacheniya, both of which may be interpreted as "special purpose". As syllabic abbreviations, they are not acronyms and are not normally capitalized.

They are general terms that were used for a variety of Soviet special operations (spetsoperatsiya) units. In addition, many Cheka and Internal Troops units (such as OMSDON) also included osobogo naznacheniya in their full names. Regular forces assigned to special tasks were sometimes also referred to by terms such as spetsnaz and osnaz.

Spetsnaz later referred specifically to special (spetsialnogo) purpose (naznacheniya) or special operations (spetsoperatsiya) forces, and the word's widespread use is a relatively recent, post-perestroika development in Russian language. The Soviet public used to know very little about their country's special forces until many state secrets were disclosed under the glasnost ("openness") policy of Mikhail Gorbachev during the late 1980s. Since then, stories about spetsnaz and their purportedly incredible prowess, from the serious to the highly questionable, have captivated the imagination of patriotic Russians, particularly in the midst of the post-Soviet era decay in military and security forces during the era of perestroika championed by Mikhail Gorbachev and continued under Boris Yeltsin. A number of books about the Soviet military intelligence special forces, such as 1987's Spetsnaz: The Story Behind the Soviet SAS by defected GRU agent Viktor Suvorov,[3] helped introduce the term to the Western public.

In post-Soviet Russia "Spetsnaz" became a colloquial term as special operations (spetsoperatsiya), from police raids to military operations in internal conflicts, grew more common. Coverage of these operations, and the celebrity status of special operations forces in state-controlled media, encouraged the public to identify many of these forces by name: SOBR, Alpha, Vityaz. The term Spetsnaz has also continued to be used in several other post-Soviet states such as Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan for their own special operations forces. In Russia, foreign special operations forces are also known as "Spetsnaz" (for example, United States special operations forces would be called "amerikanskiy spetsnaz").

Known operations

The Crabb Affair

Lionel Crabb was a British Royal Navy frogman and MI6 diver who vanished during a reconnaissance mission around a Soviet cruiser berthed at Portsmouth Dockyard in 1956. On 16 November 2007, the BBC and the Daily Mirror reported that Eduard Koltsov, a Soviet frogman, claimed to have caught Crabb placing a mine on the Ordzhonikidze hull near the ammunition depot and cut his throat. In an interview for a Russian documentary film, Koltsov showed the dagger he allegedly used as well as an Order of the Red Star medal that he claimed to have been awarded for the deed.[4][5] Koltsov, 74 at the time of the interview, stated that he wanted to clear his conscience and make known exactly what happened to Crabb.[6]

Soviet war in Afghanistan

Soviet Spetsnaz forces took part in the Soviet–Afghan War of 1979-1989 in Afghanistan, usually fighting fast insertion/extraction type warfare with helicopters. Their most famous operation, Operation Storm-333 (27 December 1979), saw Soviet Special Forces storming the Tajbeg Palace in Afghanistan and killing Afghan President Hafizullah Amin and his 200 personal guards.[7] The Soviets then installed Babrak Karmal as Amin's successor.

The operation involved approximately 660 Soviet operators dressed in Afghan uniforms, including ca. 50 KGB and GRU officers from the Alpha Group and Zenith Group. The Soviet forces occupied major governmental, military and media buildings in Kabul, including their primary target – the Tajbeg Presidential Palace.

Spetsnaz units conducted numerous air-assault missions throughout the war, including ambushes and raids. The Spetsnaz often conducted missions to ambush and destroy enemy supply-convoys.[8] The Mujahideen had great respect for the Spetsnaz, seeing them as a much more difficult opponent than the typical Soviet conscript soldier. They said that the Spetsnaz-led air assault missions had changed the complexion of the war. They also credited the Spetsnaz with closing down all the supply routes along the Afghan-Pakistani border in 1986. In April 1986 the rebels lost one of their biggest bases, at Zhawar in Paktia Province, to a Soviet Spetsnaz air-assault. The Spetsnaz achieved victory by knocking out several rebel positions above the base, a mile-long series of fortified caves in a remote canyon. The Spetsnaz also succeeded in inserting air-assault forces into regions in Konar Valley near Barikot which were previously considered inaccessible to Soviet forces.[9]

Alleged conflict with Pakistani commandos

It is believed that during the war in Afghanistan, Soviet special forces came in direct conflict with Pakistan's Special Services Group. This unit was deployed disguised as Afghans, and provided support to the Mujahideen fighting the Soviets. A battle reported as having been fought between the Pakistanis and Soviet troops took place in Kunar Province in March 1986. Soviet sources claimed that the battle was actually fought between the GRU's 15th Spetsnaz Brigade, and the Usama Bin Zaid regiment of Afghan Mujahideen under Commander Assadullah, belonging to Abdul Rasul Sayyaf's faction.[10] Fighting is also alleged to have taken place during Operation Magistral where nearly 200 Mujahideen were killed in a failed attempt to wrest the strategic Hill 3234 near the Pakistani border from a 39-man Soviet Airborne company.

The Beirut hostage crisis

In October 1985, specialist operators from the KGB's Group "A" (Alpha) were dispatched to Beirut, Lebanon. The Kremlin had been informed of the kidnapping of four Soviet diplomats by the militant group, the Islamic Liberation Organization (a radical offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood). It was believed that this was retaliation for the Soviet support of Syrian involvement in the Lebanese Civil War.[11] However, by the time Alpha arrived, one of the hostages had already been killed. It is alleged that through a network of supporting KGB operatives, members of the task force identified each of the perpetrators involved in the crisis; once these had been identified, the team began to take relatives of these militants as hostages. Following the standard Soviet policy of not negotiating with terrorists, some of the hostages taken by Alpha were dismembered, and their body parts sent to the militants. The warning was clear: more would follow unless the remaining hostages were released immediately. The show of force worked, and for 20 years, no Soviet or Russian officials was taken captive, until the 2006 abduction and murder of four Russian embassy staff in Iraq.

However, the veracity of this story has been brought into question. Another version says that the release of the Soviet hostages was the result of extensive diplomatic negotiations with the spiritual leader of Hezbollah, Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Hussein Fadlallah, who appealed to King Hussein of Jordan and the leaders of Libya and Iran to use their influence on the kidnappers.[12]

After the breakup of Soviet Union

After the collapse of the USSR, Spetsnaz forces of the Soviet Union's newly formed republics took part in many local conflicts such as the Civil war in Tajikistan, Chechen Wars, Russo-Georgian War and the Crimea Crisis. Spetsnaz forces also have been called upon to resolve several high-profile hostage situations such as the Moscow theater hostage crisis and the Beslan school hostage crisis.[13]

Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis

The crisis took place from 14 June to 19 June 1995, when a group of 80 to 200 Chechen separatists led by Shamil Basayev attacked the southern Russian city of Budyonnovsk, where they stormed the main police station and the city hall. After several hours of fighting and Russian reinforcements imminent, the Chechens retreated to the residential district and regrouped in the city hospital, where they took between 1,500 and 1,800 hostages, most of them civilians (including about 150 children and a number of women with newborn infants).[14]

After three days of siege, the Russian authorities ordered the security forces to retake the hospital compound. The forces deployed were elite personnel from the Federal Security Service's Alpha Group, alongside MVD militsiya and Internal Troops. The strike force attacked the hospital compound at dawn on the fourth day, meeting fierce resistance. After several hours of fighting in which many hostages were killed by crossfire, a local ceasefire was agreed, and 227 hostages were released; 61 others were freed by the Russian forces.

A second Russian attack on the hospital a few hours later also failed and so did a third, resulting in even more casualties. The Russian authorities accused the Chechens of using the hostages as human shields.

According to official figures, 129 civilians were killed and 415 were injured in the entire event (of whom 18 later died of their wounds).[15] This includes at least 105 hostage fatalities.[14] However, according to an independent estimate 166 hostages were killed and 541 injured in the special forces attack on the hospital.[16][17] At least 11 Russian police officers and 14 soldiers were killed.[14] Basayev's force suffered 11 men killed and one missing; most of their bodies were returned to Chechnya in a special freezer truck. In the years following the hostage-taking, more than 30 of the surviving attackers have been killed, including Aslambek Abdulkhadzhiev in 2002 and Shamil Basayev in 2006, and more than 20 were sentenced, by the Stavropol territorial court, to various terms of imprisonment.

Second Chechen war

Russian special forces were instrumental in Russia's and the Kremlin backed government's success in the Second Chechen War. Under joint command of Unified Group of Troops (OGV), GRU, FSB, MVD Spetsnaz operators conducted a myriad of counter-insurgency and counter-terrorism missions, including targeted killings of separatist leadership, in the meantime inflicting heavy casualties among Islamist separatists. Some of the most infamous of these successful missions were internationally condemned terrorists and separatist leaders, like Aslan Maskhadov, Abdul Halim Sadulayev, Dokka Umarov, Turpal-Ali Atgeriyev, Akhmed Avtorkhanov, Ibn al-Khattab, Abu al-Walid, Abu Hafs al-Urduni, Muhannad, Ali Taziev, Supyan Abdullayev, Shamil Basayev, Ruslan Gelayev, Salman Raduyev, Sulim Yamadayev, Rappani Khalilov, Yassir al-Sudani. During these many operators received honors for their courage and prowess in combat, including with the title Hero of the Russian Federation. At least 106 FSB and GRU operators died during the conflict.[18]

Moscow theater hostage crisis

The crisis was the seizure of the crowded Dubrovka Theater on 23 October 2002 by 40 to 50 armed Chechens who claimed allegiance to the Islamist militant separatist movement in Chechnya.[19] They took 850 hostages and demanded the withdrawal of Russian forces from Chechnya and an end to the Second Chechen War. The siege was officially led by Movsar Barayev.

Due to the disposition of the theater, special forces would have had to fight through 100 feet of corridor and attack up a well defended staircase, before they could reach the hall in where the hostages were held. The terrorist also had numerous explosives, with the most powerful in the center of the auditorium, that if detonated, could have brought down the ceiling and caused casualties in excess of 80 percent.[20] After a two-and-a-half-day siege and the execution of two female hostages, Spetsnaz operators from the Federal Security Service (FSB) Alpha and Vympel a.k.a. Vega Groups, supported by the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) SOBR unit, pumped an undisclosed chemical agent into the building's ventilation system and raided it.[19]

During the raid, all 40 of the attackers were killed, with no casualties among Spetsnaz, but about 130 hostages, including nine foreigners, died due to adverse reactions to the gas. Russian security agencies refused to disclose the gas used in the attack leading to doctors in local hospitals being unable to respond adequately to the influx of casualties.[21] All but two of the hostages who died during the siege were killed by the toxic substance pumped into the theater to subdue the militants.[22][23] The use of the gas was widely condemned as heavy-handed, but the American and British governments deemed Russia's actions justifiable.[24]

Physicians in Moscow condemned the refusal to disclose the identity of the gas that prevented them from saving more lives. Some reports said the drug naloxone was used to save some hostages.[25]

Beslan school siege

Also referred to as the Beslan massacre[26][27][28] started on 1 September 2004, lasted three days and involved the capture of over 1,100 people as hostages (including 777 children),[29] ending with the death of 334 people. The event led to security and political repercussions in Russia; in the aftermath of the crisis, there has been an increase in Ingush-Ossetian ethnic hostility, while contributing to a series of federal government reforms consolidating power in the Kremlin and strengthening of the powers of the President of Russia.[30]

The crisis began when a group of armed radical Islamist combatants, mostly Ingush and Chechen, occupied School Number One (SNO) in the town of Beslan, North Ossetia (an autonomous republic in the North Caucasus region of the Russian Federation) on 1 September 2004. The hostage-takers were the Riyadus-Salikhin Battalion, sent by the Chechen terrorist warlord Shamil Basayev, who demanded recognition of the independence of Chechnya at the United Nations and the withdrawal of Russian forces from Chechnya.

On the third day of the standoff, counter terrorism units stormed the building using heavy weapons after several explosions rocked the building and children started escaping. It was in this chaos most of the officers were killed, trying to protect escaping children from gun fire.[31][32] At least 334 hostages were killed as a result of the crisis, including 186 children.[33][34] Official reports on how many members of Russia's special forces died in the fighting varied from 11, 12, 16 (7 Alpha and 9 Vega) to more than 20[35] killed. There are only 10 names on the special forces monument in Beslan.[36] The fatalities included all three commanders of the assault group: Colonel Oleg Ilyin, Lieutenant Colonel Dmitry Razumovsky of Vega, and Major Alexander Perov of Alpha.[37] At least 30 commandos suffered serious wounds.[38]

The attack also marked the end to the mass terrorism in the North Caucasus separatist conflict until 2010, when two Dagestani female suicide bombers attacked two railway stations in Russia. After Beslan, there was a period of several years without suicide attacks in and around Chechnya.

Lessons learned

By the mid 2000s, the special forces gained a firm upper hand over separatists and terrorist attacks in Russia dwindled, falling from 257 in 2005 to 48 in 2007. Military analyst Vitaly Shlykov praised the effectiveness of Russia's security agencies, saying that the experience learned in Chechnya and Dagestan had been key to the success. In 2008, the American Carnegie Endowment's Foreign Policy magazine named Russia as "the worst place to be a terrorist", particularly highlighting Russia's willingness to prioritize national security over civil rights.[40] By 2010, Russian special forces, led by the FSB, had managed to eliminate the top leadership of the Chechen insurgency, except for Dokka Umarov.[41]

From 2009, the level of terrorism in Russia increased again. Particularly worrisome was the increase in suicide attacks. While between February 2005 and August 2008, no civilians were killed in such attacks, in 2008 at least 17 were killed and in 2009 the number rose to 45.[42] In March 2010, Islamist militants organised the 2010 Moscow Metro bombings, which killed 40 people. One of the two blasts took place at Lubyanka station, near the FSB headquarters. Militant leader Doku Umarov—dubbed "Russia's Osama Bin Laden"—took responsibility for the attacks. In July 2010, President Dmitry Medvedev expanded the FSB's powers in its fight against terrorism.

In 2011, Federal Security Service exposed 199 foreign spies, including 41 professional spies and 158 agents employed by foreign intelligence services.[43] The number has risen in recent years: in 2006 the FSB reportedly caught about 27 foreign intelligence officers and 89 foreign agents.[39] Comparing the number of exposed spies historically, the then-FSB Director Nikolay Kovalyov said in 1996: "There has never been such a number of spies arrested by us since the time when German agents were sent in during the years of World War II." The 2011 figure is similar to what was reported in 1995–1996, when around 400 foreign intelligence agents were uncovered during the two-year period.[44]

Anti terrorist operations prior to 2014 Sochi Olympics

Olympic organizers received several threats prior to the Games. In a July 2013 video release, Chechen Islamist commander Dokka Umarov called for attacks on the Games, stating that the Games were being staged "on the bones of many, many Muslims killed ...and buried on our lands extending to the Black Sea."[45] Threats were received from the group Vilayat Dagestan, which had claimed responsibility for the Volgograd bombings under the demands of Umarov, and a number of National Olympic Committees had also received threats via e-mail, threatening that terrorists would kidnap or "blow up" athletes during the Games.

In response to the insurgent threats, Russian special forces began cracking down on suspected terrorist organizations, making several arrests and claiming to have curbed several plots,[46] and killed numerous Islamist leaders including Eldar Magatov, a suspect in attacks on Russian targets and alleged leader of an insurgent group in the Babyurt district of Dagestan.[47] Dokka Umarov himself was poisoned on August 6, 2013 and died on September 7, 2013.[48]

The operations were a success and the Olympics went down without any major terrorist incident.

2014 intervention in Ukraine

Spetsnaz unit of the VDV RF took part in the 2014 Crimean crisis. Several hundred members of the 45th Detached Guards Spetsnaz Regiment and the 22nd Spetsnaz brigade were sent in, disguised as civilians.[49][50][51][52]

Insurgency in the Caucasus

Although crime has been markedly reduced and stability increased throughout Russia compared to the previous year, about 350 militants in the North Caucasus have been killed in anti-terror operations in the first four months of 2014, according to an announcement by Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev in the State Duma.[53]

On September 23, 2014, Russian news agencies marked the 15th anniversary of the formation of the Unified Group of Troops (OGV, or ОГВ) in the North Caucasus. The OGV is the inter-service headquarters established at Khankala, Chechnya to command all Russian (MOD, MVD, FSB) operations from the start of the second Chechen war in 1999.

Since its inception, the OGV combined operations has conducted 40,000 special missions, destroyed 5,000 bases and caches, confiscated 30,000 weapons, and disarmed 80,000 explosive devices and in the process has killed over 10,000 insurgents in the time frame of 15 years. The Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) noted that the decoration Hero of the Russian Federation has been awarded to 93 MVD servicemen in the OGV (including 66 posthumously). Overall, more than 23,000 MVD troops have received honors for their conduct during operations.[54]

Russian spetsnaz forces participated in the 2014 Grozny clashes.[55]

Syrian Civil War

Unidentified spetsnaz units are allegedly involved in search and destroy operations, target acquisition for Russian ground attack aircraft and special reconnaissance.[56]

Timeline

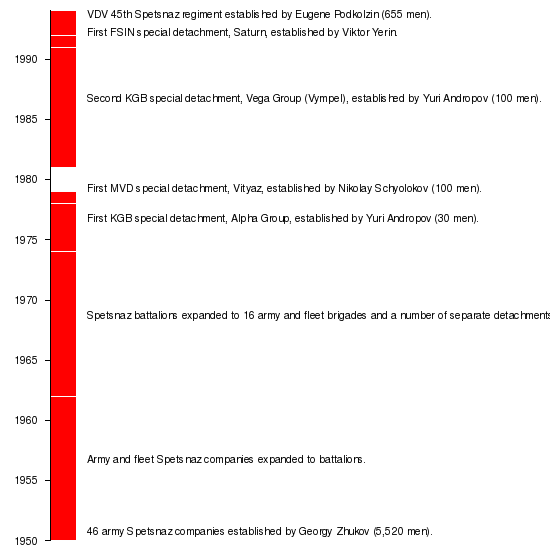

The concept of using special tactics and strategies was originally proposed by Russian military theorist Mikhail Svechnykov (executed during the Great Purge in 1938), who envisaged the development of unconventional warfare capabilities to overcome disadvantages faced by conventional forces in the field. Its implementation was begun by the "grandfather of the spetsnaz", Ilya Starinov.

During World War II, the Red Army reconnaissance and sabotage detachments were formed under the supervision of the Second Department of the General Staff of the Soviet Armed Forces. These forces were subordinate to front commanders.[57] The infamous NKVD internal security and espionage agency also had their own special purpose (osnaz) detachments, including many saboteur teams who were airdropped into enemy-occupied territories to work with (and often take over and lead) the Soviet Partisans.

In 1950, Georgy Zhukov advocated the creation of 46 military spetsnaz companies, each consisting of 120 servicemen. This was the first use of "spetsnaz" to denote a separate military branch since World War II. These companies were later expanded to battalions and then to brigades. However, some separate companies (orSpN) and detachments (ooSpN) existed with brigades until the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

The special purpose forces of the Armed Forces of the RF included fourteen land brigades, two naval brigades and a number of separate detachments and companies, operating under the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) and collectively known as Spetsnaz GRU. These units and formations existed in the highest possible secrecy, and were disguised as Soviet paratroopers (Army spetsnaz) or naval infantrymen (Naval spetsnaz) by their uniforms and insignia.

Twenty-four years after the birth of Spetsnaz, the first counter-terrorist unit was established by the Chairman of the KGB gen. Yuri Andropov. From the late 1970s through the 1980s, a number of special-purpose units were created in the KGB and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD).

During the 1990s, special detachments were established within the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) and the Airborne Troops (VDV). Some civil agencies with non-police functions have created special units also known as Spetsnaz, such as the Leader special centre in the Ministry of Emergency Situations (MChS).

2013 saw the creation of the Special Operations Forces of the Russian Federation encompassing all special military units in the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation.

Soviet and Russian nomenclature

- Soviet (Russian) Ministry of Defence special forces:

- Spetsnaz GRU units (under GRU, later the Russian Ground Forces)

- Naval Spetsnaz units (Russian Navy)

- 45th Guards Spetsnaz Brigade (Russian Airborne Troops)

- State security (KGB-FSB) special forces:

- Special Operations Center (TsSN): A, B, Special Purpose Service

- Regional FSB special forces

- Zaslon (belonging to Foreign Intelligence Service)

- Defunct KGB units such as Cascade, Omega, Zenith

- Special Purpose Regiment (Kremlin Regiment)

- Border Troops special units

- Former Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) special forces, which from 2016 report as part of the National Guard of Russia, including the National Guard Forces Command:

- Internal Troops' Division of Operational Purpose (OMSDON-ODON) and OBRON

- Rus and Vityaz (merged into the 604th Special Purpose Center)

- Other Internal Troops special units

- Militsiya/Politsiya special forces (OMON, SOBR-OMSN, Berkut)

- "Kadyrov's spetsnaz"

- Ministry of Justice special forces:

- Independent regional detachments such as Saturn

Soviet and Russian military special forces

The elite units of the Soviet Armed Forces and Armed Forces of the Russian Federation are controlled, for the most part, by the military-intelligence GRU (Spetsnaz GRU) under the General Staff. They were heavily involved in secret operations and training pro-Soviet forces during the Cold War and in the wars in Afghanistan during the 1980s and Chechnya during the 1990s and 2000s. In 2010, as a result of the 2008 Russian military reform, GRU special forces came under the control of the Russian Ground Forces, being "directly subordinated to commanders of combined strategic commands."[58] However, in 2013, these Spetsnaz forces were placed back under the GRU, under the wings of the newly formed Special Operations Forces of the Russian Federation. The Russian Airborne Troops (VDV, a separate branch of the Soviet and Russian Armed Forces) includes the 45th Guards Spetsnaz Brigade.

Most Russian military special forces units are known by their type of formation (company, battalion or brigade) and a number, like other Soviet or Russian military units. Two exceptions were the ethnic Chechen Special Battalions Vostok and Zapad (East and West) that existed during the 2000s. Below is a 2012 list of special purpose units in the Russian Armed Forces:[59][60]

- Special Operations Forces of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, subordinate directly to the MoD/General Staff[61][62]

- Combined Arms

- Voennay Razvedka (Military intelligence) personnel/units within larger formations in ground troops, airborne troops and marines. Intelligence battalion in the divisions, reconnaissance company in the brigade, a reconnaissance platoon in the regiment.

- 2nd Special Purpose Brigade in Promezhitsa, Pskov Oblast

- 3rd Special Purpose Brigade in Tolyatti

- 10th Special Purpose Brigade in Mol'kino, Krasnoyarsk Territory

- 14th Special Purpose Brigade in Ussuriysk

- 16th Special Purpose Brigade in Tambov

- 22nd Special Purpose Guards Brigade in Stepnoi, Rostov Oblast

- 24th Special Purpose Brigade in Irkutsk

- Naval Special Operations Units

- 442nd Detached Naval Reconnaissance Spetsnaz Point (omrpSpN – Pacific Fleet)

- 420th Detached Naval Reconnaissance Spetsnaz Point (omrpSpN – Northern Fleet)

- 431st Detached Naval Reconnaissance Spetsnaz Point (omrpSpN – Black Sea Fleet)

- 561st Detached Naval Reconnaissance Spetsnaz Point (omrpSpN – Baltic Fleet)

KGB of the USSR and FSB of the Russian Federation special forces

The Center of Special Operations of the FSB (CSN FSB, центр специального назначения ФСБ) is officially tasked with combating terrorism and protecting the constitutional order of the Russian Federation. The CSN FSB consists of estimated 4,000 operators[68] in three operative divisions:

- Directorate "A" (Spetsgruppa Alpha)

- Directorate "B" (Spetsgruppa Vega)

- Directorate "C" (Spetsgruppa Smerch)

- Regional FSB units

CSN FSB headquarters is a large complex of buildings and training areas, with dozens of hectares of land and scores of training facilities. The average training period for a CSN officer is about five years.[69]

Spetsgruppa 'A' (Alpha Group) is a counter-terrorist unit created in 1974. It is a professional unit, consisting of about 700 operators and support personnel in five operational detachments. Most are stationed in Moscow, with the remainder in three other cities: Krasnodar, Yekaterinburg and Khabarovsk. All Alpha operators undergo airborne, mountain and counter-sabotage dive training. Alpha has operated in other countries, most notably Operation Storm-333 (when Alpha and Zenith detachments supported the 154th Independent Spetsnaz Detachment—known as the "Muslim Battalion"—of the GRU on a mission to overthrow and kill Afghan president Hafizullah Amin).[70]

Spetsgruppa "B" (Vympel, also known as "Vega" in period 1993-1995) was formed in 1981, merging two elite Cold War-era KGB special units—Cascade (Kaskad) and Zenith (Zenit)—which were similar to the CIA's Special Activities Division (responsible for clandestine / covert operations involving sabotage and assassination in other countries) and re-designated for counter-terrorist and counter-sabotage operations. It is tasked with the protection of strategic installations, such as factories and transportation centers. With its Alpha counterparts, it is heavily used in the North Caucasus. Vympel has four operative units in Moscow, with branch offices in nearly every city containing a nuclear power plant.

Spetsgruppa "C", or Smerch, but also known as the Service of Special Operations (ССО), is a relatively new unit formed in July 1999. Officers from Smerch are frequently involved with the capture and transfer of various bandit and criminal leaders who help aid disruption in the North Caucasus and throughout Russia. Operations include both direct action against bandit holdouts in Southern Russia as well as high-profile arrests in more densely populated cities and guarding government officials. Because of its initials, this group is casually referred to as “Smerch”. With the Center of Special Operations and its elite units, many FSB special forces units operate at the regional level. These detachments are usually known as ROSN or ROSO (Regional Department of Special Designation), such as Saint Petersburg's Grad (Hail) or Murmansk's Kasatka (Orca).

Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation

The SVR RF, formerly the First Chief Directorate of the KGB of the USSR, has its own top secret special force known as Zaslon (Заслон) (meaning Screen, Barrier or Shield) about which extremely little is known.

Within the Operations Department of Directorate S, there is the elite Special Operations Group called Zaslon. Formerly in PGU KGB SSSR called Vympel (e.g. French counterpart; Division Action). However, mere existence of such group within SVR is denied by Russian authorities. Nevertheless, there were some rumors that such group does indeed exist and is assigned to execute very special operations abroad primarily for protection of Russian embassy personnel and internal investigations. It is believed that the group is deep undercover and consists of approximately 300-500 highly experienced operatives speaking several languages and having extensive record of operations while serving in other secret units of the Russian military.[71][72][73]

Soviet MVD and Russian National Guard special forces

The special missions units of the National Guard of Russia (consolidated and replaced the forces of the MVD Internal Troops, SOBR, OMON) includes a number of Russian Internal Troops (VV, successor to the Soviet Internal Troops) paramilitary units to combat internal threats to the government, such as insurgencies and mutinies. These units usually have a unique name and official OSN number, and some are part the ODON (also known as Dzerzhinsky Division). OBrON (Independent Special Designation Brigade) VV special groups (spetsgruppa) were deployed to Chechnya.[74]

Internal Troops

The following is a list of Internal Troops OSNs (отряд специального назначения, "special purpose detachment") in 2012:[75]

- Dzerzhinsky Division (O.D.O.N.)

- 604th Special Purpose Center

- 7th OSN Rosich (Novocherkassk)

- 12th OSN Ural (Nizhny Tagil)

- 15th OSN Vyatich (Armavir)

- 17th OSN Edelveys (Mineralnye Vody)

- 19th OSN Ermak (Novosibirsk)

- 20th OSN (Saratov)

- 21st OSN Tayfun (Sosnovka)

- 23rd OSN Mechel (Chelyabinsk)

- 25th OSN Merkuriy (Smolensk)

- 26th OSN Bars (Kazan)

- 27th OSN Kuzbass (Kemerovo)

- 28th OSN Ratnik (Arkhangelsk)

- 29th OSN Bulat (Ufa)

- 33rd OSN Peresvet (Moscow)

- 34th OSN (Grozny)

Police

In addition to Internal Troops, the MVD has Politsiya (formerly Militsiya) police special forces stationed in nearly every Russian city. Most of Russia's special-police officers belong to OMON units, which are primarily used as riot police and not considered an elite force—unlike the SOBR (known as the OMSN from 2002 to 2011) rapid-response units consisting of experienced, better-trained and -equipped officers. The Chechen Republic has unique and highly autonomous special police formations, supervised by Ramzan Kadyrov and formed from the Kadyrovtsy, including the (Akhmad or Akhmat) Kadyrov Regiment ("Kadyrov's Spetsnaz").

Other MVD agencies

.jpg)

Federal Drug Control Service of Russia

- OSN "Grom"

Ministry of Justice

The Ministry of Juctice maintains several spetnaz organizations:

The following is a list of Federal Penitentiary Service OSNs:

- OSN "Fakel"[76]

- OSN "Rossy"[77]

- OSN "Akula"[78]

- OSN "Ajsberg"[79]

- OSN "Gyurza"[80]

- OSN "Korsar"[81]

- OSN "Rosomakha"[82]

- OSN "Sokol"[83]

- OSN "Saturn"[84]

- OSN "Tornado"

- OSN "Kondor"

- OSN "Yastreb"[85]

- OSN "Berkut"[86]

- OSN "Grif"[87]

- OSN "Titan"[88]

- OSN "Gepard"[89]

- OSN Saturn.

Spetsnaz units in other post-Soviet countries

Belarusian Spetsnaz

The 5th Spetsnaz Brigade is a special forces brigade of the Armed Forces of Belarus, formerly part of the Soviet Spetsnaz.[90] In addition, the State Security Committee (KGB) of Belarus that was formed from the inherited personnel and operators after the break up of the Soviet Union. KGB of Belarus has its own Spetsgruppa "A" (Alpha Group), which is the country's primary counter-terrorism unit.[91]

Kazakh Spetsnaz

As with many post Soviet states, Kazakhstan adopted the term Alpha Group to be used by its special forces. The Almaty territorial unit of Alpha was turned into the special unit Arystan (meaning "Lions" in Kazakh) of the National Security Committee (KNB) of Kazakhstan.[92] In 2006, five members of Arystan were arrested and charged with the kidnapping of the opposition politician Altynbek Sarsenbayuly, his driver, and his bodyguard; the three victims were then allegedly delivered to the people who murdered them.[93]

Kokhzal (meaning wolf pack in Kazakh language) is a special forces unit of Kazakhstan responsible for carrying out anti terror operations as well as serving as a protection detail for the President of Kazakhstan.[94]

Ukrainian Spetsnaz

Like all post-Soviet states, Ukraine inherited its Spetsnaz units from the remnants of the Soviet armed forces, GRU and KGB units. Ukraine now maintains its own Spetsnaz structure under the control of the Ministry of Interior, and under the Ministry of Defense, while the Security Service of Ukraine maintains its own Spetsnaz force, the Alpha group. The term "Alpha" is also used by many other post Soviet states such as Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan as these units are based on the Soviet Union's Alpha Group. Ukraine's Berkut special police force gained mainstream attention during the 2014 Ukrainian revolution as it was alleged to have been used by the government to quell the uprising. However, this is disputed as many officers were also wounded and killed in the action.[95]

See also

References

- ↑ Stanislav Lunev. "The Degradation of Russia's Special Forces". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "5th independent Special Forces Brigade GRU". 3 Oct 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ Suvorov, Victor (1987). Spetsnaz. The Story Behind the Soviet SAS. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. ISBN 0-241-11961-8.

- ↑ Nick Webster and Claire Donnelly (17 November 2007). "Cold war spy riddle ends". Daily Mirror. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ↑ "Russian 'killed UK diver' in 1956". BBC. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ↑ Williams, David (16 November 2007). "Cold War mystery solved? I killed Buster Crabb says Russian frogman". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ↑ McCauley, Martin (2008). Russia, America and the Cold War: 1949–1991 (Revised 2nd ed.). Harlow, UK: Pearson Education. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ ""Soviet Special Forces (Spetsnaz): Experience in Afghanistan" by Gusinov, Timothy - Military Review, Vol. 82, Issue 2, March/April 2002 - Online Research Library: Questia". questia.com.

- ↑ [÷http://articles.latimes.com/1986-05-24/news/mn-7472_1_soviet-union/2 "Afghan Rebels Face Tougher Foe in Elite Soviet Commando Units"] Check

|url=value (help). latimes. - ↑ Lester W. Grau & Ali Ahmed Jalali, Forbidden Cross-Border Vendetta: Spetsnaz Strike into Pakistan during the Soviet-Afghan War Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Journal of Slavic Military Studies, December 2005, p.1-2 Referenced copy was obtained via the Foreign Military Studies Office website

- ↑ "Terrorist Organization Profile: Islamic Liberation Organization". University of Maryland. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Вячеслав Лашкул. Бейрутская операция советской разведки/Vyacheslav Lashkul" [The Beirut Soviet intelligence operations] (in Russian). Chekist.ru. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ "18 famous and infamous special forces missions". CNN. 7 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 (in Russian) Буденновск Archived October 6, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ History of Chechen rebels' hostage taking Archived September 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Gazeta.Ru, 24 October 2002

- ↑ Russia: A Timeline Of Terrorism Since 1995, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 30 August 2006

- ↑ Adam Dolnik, Understanding Terrorist Innovation: Technology, Tactics and Global Trends, 2007 (p. 105)

- ↑ "The Second Chechen War". The History Guy. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Modest Silin, Hostage, Nord-Ost siege, 2002". Russia Today. 27 October 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008.

- ↑ "The Moscow Theatre Siege Documentary". YouTube. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Moscow theatre siege: Questions remain unanswered Archived January 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. BBC Retrieved on 2013-16-13

- ↑ "Gas "killed Moscow hostages", ibid.".

- ↑ "Moscow court begins siege claims" Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News, 24 December 2002

- ↑ "Moscow siege gas 'not illegal'". BBC News. 29 October 2002. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Mystery of Russian gas deepens". New Scientist. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ Beslan mothers' futile quest for relief Archived August 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News, 4 June 2005

- ↑ "United States Expresses Sympathy on Anniversary of Beslan Attack". US Department of State. 31 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Putin's legacy is a massacre, say the mothers of Beslan". The Independent. 26 February 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Beslan - Two Years On". UNICEF. 31 August 2006. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Chechnya Vow Cast a Long Shadow". The Moscow Times. 26 February 2008. Archived from the original on 13 August 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Beslan School Massacre, Dramatic Scenes (2004)". YouTube. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ Satter, David (13 November 2006). "The Truth About Beslan. What Putin's government is covering up.". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Woman injured in 2004 Russian siege dies". The Boston Globe. 8 December 2006. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ "Putin meets angry Beslan mothers". BBC News. 2 September 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- ↑ Hostage Takers in Russia Argued Before Explosion, The Washington Post, 7 September 2004

- ↑ "Monument to special forces and rescuers unveiled in Beslan". NEWS.rin.ru. 2 September 2006. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "More and more evidence implicates authorities in Beslan disaster. Beslan's tragic end: Spontaneous or planned?". jamestown.org. 18 October 2004. Archived from the original on 20 October 2004. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "After School Siege, Russia Also Mourns Secret Heroes". The New York Times. 13 September 2004. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Story to the Day of Checkist". grani.ru.

- ↑ Biberman, Yelena (6 December 2008). "No Place to Be a Terrorist". Russia Profile.

- ↑ Saradzhyan, Simon (31 March 2010). "Eliminating Terrorists, Not Terror". International Relations and Security Network.

- ↑ Saradzhyan, Simon (23 December 2010). "Russia's North Caucasus, the Terrorism Revival". International Relations and Security Network.

- ↑ "Russia Busted 200 Spies Last Year – Medvedev". RIA Novosti. 7 February 2012.

- ↑ Counterintelligence Cases Archived August 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., by GlobalSecurity.org

- ↑ "Caucasus Emirate Leader Calls On Insurgents To Thwart Sochi Winter Olympics". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ "Inside Russia's pre-Olympics terrorist crackdown". NBC News. 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Russian police kill Islamist militant leader before Olympics". canoe.ca. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ http://www.rferl.org/content/insurgency-commanders-divulge-of-umarovs-death/25467747.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Ukraine crisis: Pretext and plotting behind Crimea's occupation". Financial Times. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Willis Raburu (17 April 2014). "Putin admits unmarked soldiers in Ukraine were Russian; optimistic about Geneva talks". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ "Photos and roses for GRU’s ‘spetsnaz’ casualties". Financial Times. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ George Woloshyn (26 December 2014). "George Woloshyn: Take the fight to the enemy". Kyiv Post. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ "МВД России ликвидировало за 4 месяца более 350 боевиков". Новости Mail.Ru. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "ОГВ на Кавказе за 15 лет уничтожила более 10 тысяч боевиков". РИА Новости. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Heavy Fighting And Firefights In Grozny Chechenya - December 4th 2014". Live Leak.

- ↑ "UK Mirror: Russian Spetsnaz Special Forces Sent In to Protect Assad". Newsmax.

- ↑ Carey Schofield, The Russian Elite: Inside Spetsnaz and the Airborne Forces, Greenhill, London, 1993, p.34-37

- ↑ Roger McDermott, Bat or Mouse? The Strange Case of Reforming Spetsnaz Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 7 Issue: 198, November 2, 2010.

- ↑ ГРУ (Главное Разведывательное Управление) ГШ ВС РФ. Russian Military Analysis (in Russian). Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Военно-Морской Флот. Russian Military Analysis (in Russian). Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "О новом спецназе замолвите слово". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ "Lenta.ru: Россия: Общество: В России создали командование сил спецопераций". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ Alexei Mikhailov (2012-12-03). "Russian militaries want to create special commando force | Russia Beyond The Headlines". Rbth.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ↑ "Lenta.ru: Оружие: Вооружение: В Кубинке создадут Центр специальных операций". Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ John Pike. "Spetsnaz Order of Battle". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ John Pike. "45th Special Purpose Regiment". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ John Pike. "Naval Spetsnaz [Spetsialnaya Razvedka]". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Sakwa, Richard. Russian Politics and Society (4th ed.). p. 98.

- ↑ "FSB Special forces: 1998–2010". Agentura.ru. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Take-Down of Kabul: An Effective Coup de Main". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "Vietnamdefence.com - Tin Quân sự 24h". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Special force deployment to Syria may signal Moscow’s doubts". BLOUIN BEAT: Politics. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Russian Zaslon Special Operations - Business Insider". Business Insider. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Patrick E. Tyler (25 January 2002). "Police in Chechnya Accuse Russia's Troops of Murder". New York Times. Russia; Chechnya (Russia). Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Министерство Внутренних Дел (МВД). Russian Military Analysis (in Russian). Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ "ОСН "Факел" УФСИН России по Московской области принял участие в Международной выставке "Интерполитех-2013"". Federal Penal Service. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ "Отдел специального назначения "Россы" ГУФСИН России по Свердловской области отпраздновал 21-ю годовщину со дня создания". The Federal Penal Service. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "В ОСН(б) "Акула" УФСИН России по Краснодарскому краю прошли испытания на право ношения крапового берета". FPS of Russia, Krasnodar Territory. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Офицеры ОСН АЙСБЕРГ - Официальный сайт Филиала "Красная Поляна" Южного межрегионального учебного центра ФСИН России". Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Отдел специального назначения "Гюрза" УФСИН России по Республике Калмыкия отметил 20-ти летие". FPS of Russia, Republic of Kalmykia. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "ОСН ГУФСИН России по Новосибирской области "Корсар" исполнилось 20 лет". Federal Penal Service. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Сотрудники ОСН "Росомаха" УФСИН Росси по Ямало-Ненецкому автономному округу признаны победителями регионального чемпионата по рукопашному бою". Federal Penal Service. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "В ОСН "Сокол" УФСИН России по Белгородской области прошёл День открытых дверей". FPS of Russia, Belgorod region. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "ОСН "Сатурн" Официальный сайт". OSN "Saturn", Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia in Moscow. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ ru:Ястреб (спецподразделение)

- ↑

- ↑ "Страница памяти. Отдел специального назначения "ГРИФ"". OSN "Grif" memorial page. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Из Чечни вернулся липецкий отряд спецназа "Титан"". Gorod48.ru. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Вестник Мордовии: Бойцы спецназа "Гепард" сразились за краповый берет (фоторепортаж)". The Mordovian Bulletin. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "5th independent Special Forces Brigade". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "The State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Mariya Y. Omelicheva, Counterterrorism Policies in Central Asia, page 119.

- ↑ Kazakh security officers suspected of kidnapping, not murdering oppositionist. Archived September 27, 2013, at the Wayback Machine., BBC Monitoring International Reports, 22 February 2006.

- ↑ "SPECIAL FORCES OF KAZAKHSTAN (2007)". Kazakh military site.

- ↑ "Special Report: Flaws found in Ukraine's probe of Maidan massacre". Reuters. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

Sources

- Viktor Suvorov, Spetsnaz: The Story Behind the Soviet SAS, Hamish Hamilton, London 1987

- David C. Isby, Weapons and Tactics of the Soviet Army, Jane's Publishing Company Limited, London, 1988

- Carey Schofield, The Russian Elite: Inside Spetsnaz and the Airborne Forces, Greenhill, London, 1993

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spetsnaz. |

- Systema Spetsnaz International Center

- (in Russian) Official website of the Russian Interior Ministry special forces

- Agentura.ru – Special operations forces

- (in Russian) Internet portal of Russian special forces