Orthograde posture

Orthograde is a term derived from (Greek ὀρθός, orthos ("right", "true", "straight") + Latin gradi (to walk)] that describes a manner of walking which is upright, with the independent motion of limbs.

Both New and Old World monkeys are primarily arboreal, and they have a tendency to walk with their limbs swinging in parallel to one another. This differs from the manner of walking demonstrated by the apes.

Chimpanzees, gorillas, and humans, when walking, walk upright, and their limbs swing in opposition to one another for balance (unlike monkeys, apes lack a tail to use for balance). Disadvantages related to upright walking do exist for primates, since their primary mode of locomotion is quadrupedalism. This upright locomotion is called "orthograde posture". Orthograde posture in humans was made possible through millions of years of evolution. In order to walk upright with maximum efficiency, the skull, spine, pelvis, lower limbs, and feet all underwent evolutionary changes.

Evolutionary Significance

The first definitive evidence of habitual orthograde posture in human evolutionary lineage begins with Ardipithecus ramidus kadabba, dating between 5.2 to 5.8 million years ago. The skeletal remains of this hominid exhibit a mosaic of morphological characteristics that would have been both adapted to an arboreal environment and walking upright terrestrially.[1] The earliest evidence of a hominid exhibiting skeletal morphology capable of achieving orthograde posture dates to 9.5 million years ago, with the discovery of a Miocene ape, Dryopithecus in Can Llobateres, Spain.[2]

Morphological Characteristics

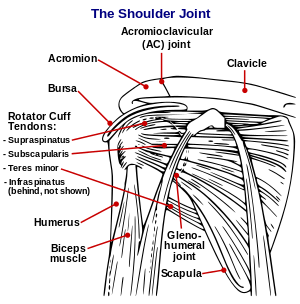

In order for animals to have the ability to walk upright, there are certain anatomical requirements. For mammals that exhibit orthograde posture, the scapula is more dorsally placed than in animals with a pronograde posture.[3] The scapular index, the measure of width to length of the scapula, is decreased in animals exhibiting orthograde posture. This means that the scapula is broader than it is long. The rib cage is more flattened and the acromion process on the scapula is much larger. This is because there is more of a need for the deltoid muscle in orthograde posture, due to the availability of resource manipulation by the freeing up of hands.

See also

Further reading

- Crompton, RH; Vereecke, EE; Thorpe, SK (2008). "Locomotion and posture from the common hominoid ancestor to fully modern hominins, with special reference to the last common panin/hominin ancestor". Journal of Anatomy. 212 (4): 501–43. PMC 2409101

. PMID 18380868. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00870.x.

. PMID 18380868. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00870.x. - What Does It Mean to Be Human? Walking Upright. Accessed September 21, 2015. http://humanorigins.si.edu/human-characteristics/walking

- Kottak, Conrad Phillip. Windows On Humanity: A Concise Introduction to Anthropology. McGraw-Hill. New York, NY. 2005. pg. 80. ISBN 978-0073258935.

- orthograde in Dorland's Medical Dictionary

References

- ↑ Niemitz, Carsten (March 2010). "The evolution of the upright posture and gait—a review and a new synthesis". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (3): 241–63. Bibcode:2010NW.....97..241N. PMC 2819487

. PMID 20127307. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0637-3.

. PMID 20127307. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0637-3. - ↑ Moyà-Solà, Salvador; Köhler, Meike (1996). "A Dryopithecus skeleton and the origins of great-ape locomot". Nature. 379 (6561): 156–159. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..156M. PMID 8538764. doi:10.1038/379156a0.

- ↑ Bain, Gregory I; Itoi, Eiji; Di Giacomo, Giovanni; Sugaya, Hiroyuki (2015). Normal and Pathological Anatomy of the Shoulder. Springer. pp. 403–413. ISBN 3662457199.