July Monarchy

| Kingdom of France | ||||||||||

| Royaume de France | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

.svg.png) Royal Coat of arms

| ||||||||||

| Anthem La Parisienne "The Parisian" | ||||||||||

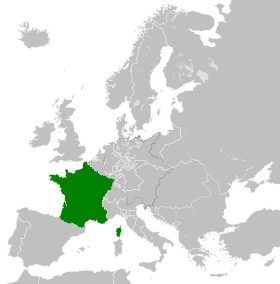

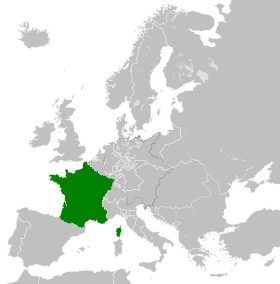

The French Kingdom in 1839 | ||||||||||

| Capital | Paris | |||||||||

| Languages | French | |||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism Calvinism Lutheranism Judaism | |||||||||

| Government | Constitutional monarchy | |||||||||

| King of the French | ||||||||||

| • | 1830–1848 | Louis Philippe I | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||

| • | 1830 | Victor de Broglie (first) | ||||||||

| • | 1848 | Louis-Mathieu Molé (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||||||

| • | Upper house | Chamber of Peers | ||||||||

| • | Lower house | Chamber of Deputies | ||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | July Revolution | 26 July 1830 | ||||||||

| • | Constitution adopted | 7 August 1830 | ||||||||

| • | French Revolution | 23 February 1848 | ||||||||

| Currency | French franc | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

The July Monarchy (French: Monarchie de Juillet) was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under Louis Philippe I, starting with the July Revolution of 1830 and ending with the Revolution of 1848. It began with the overthrow of the conservative government of Charles X and the House of Bourbon. Louis Philippe, a member of the more liberal Orléans branch of the House of Bourbon, proclaimed himself Roi des Français ("King of the French") rather than "King of France", emphasizing the popular origins of his reign. The king promised to follow the "juste milieu", or the middle-of-the-road, avoiding the extremes of the conservative supporters of Charles X and radicals on the left. The July Monarchy was dominated by wealthy bourgeoisie and numerous former Napoleonic officials. It followed conservative policies, especially under the influence (1840–48) of François Guizot. The king promoted friendship with Great Britain and sponsored colonial expansion, notably the conquest of Algeria. By 1848, a year in which many European states had a revolution, the king's popularity had collapsed and he was overthrown.

Overview

Louis Phillipe was pushed to the throne by an alliance between the people of Paris; the republicans, who had set up barricades in the capital; and the liberal bourgeoisie. However, at the end of his reign the so-called "Citizen King" was overthrown by similar barricades during the February Revolution of 1848, which led to the proclamation of the Second Republic.[1] After Louis-Philippe's ousting and subsequent exile to Britain, the liberal Orleanist faction (opposed by the counter-revolutionary Legitimists) continued to support a return of the House of Orléans to the throne, but the July Monarchy proved to be the last Bourbon-Orleans monarchy of France (although monarchy would return once more, under Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew, who reigned as Napoleon III from 1852–1870). The Legitimists withdrew from the political stage to their castles, leaving the stage opened for the struggle between the Orleanists and the Republicans.

The July Monarchy (1830–1848) is generally seen as a period during which the haute bourgeoisie was dominant, and marked the shift from the counter-revolutionary Legitimists to the Orleanists, who were willing to make some compromises with the changes brought by the 1789 Revolution. Louis-Philippe was crowned "King of the French", instead of "King of France": this marked his acceptance of popular sovereignty.

Louis-Philippe, who had flirted with liberalism in his youth, rejected much of the pomp and circumstance of the Bourbons and surrounded himself with merchants and bankers. The July Monarchy, however, remained a time of turmoil. A large group of Legitimists on the right demanded the restoration of the Bourbons to the throne. On the left, Republicanism and, later Socialism, remained a powerful force. Late in his reign Louis-Philippe became increasingly rigid and dogmatic and his President of the Council, François Guizot, had become deeply unpopular, but Louis-Philippe refused to remove him. The situation gradually escalated until the Revolutions of 1848 saw the fall of the monarchy and the creation of the Second Republic.

However, during the first few years of his reign, Louis-Philippe appeared to move his government toward legitimate, broad-based reform. The government found its source of legitimacy within the Charter of 1830, written by reform-minded members of Chamber of Deputies and committed to a platform of religious equality, the empowerment of the citizenry through the reestablishment of the National Guard, electoral reform, reform of the peerage system, and the lessening of royal authority. And indeed, Louis-Phillipe and his ministers adhered to policies that seemed to promote the central tenets of the constitution. However, the majority of these policies were veiled attempts to shore up the power and influence of the government and the bourgeoisie, rather than legitimate attempts to promote equality and empowerment for a broad constituency of the French population. Thus, though the July Monarchy seemed to move toward reform, this movement was largely illusory.

During the years of the July Monarchy, enfranchisement roughly doubled, from 94,000 under Charles X to more than 200,000 by 1848. However, this still represented only roughly one percent of population, and as the requirements for voting were tax-based, only the wealthiest gained this privilege. By implication, the extended franchise tended to favor the wealthy merchant bourgeoisie more than any other group. Beyond simply increasing their presence within the Chamber of Deputies, this electoral enlargement provided the bourgeoisie the means by which to challenge the nobility on legislative matters. Thus, while appearing to honor his pledge to increase suffrage, Louis-Philippe acted primarily to empower his supporters and increase his hold over the French Parliament. The inclusion of only the wealthiest also tended to undermine any possibility of the growth of a radical faction in Parliament, effectively serving socially conservative ends.

The reformed Charter of 1830 limited the power of the King—stripping him of his ability to propose and decree legislation, as well as limiting his executive authority. However, the King of the French still believed in a version of monarchy that held the king to be much more than a figurehead for an elected Parliament, and as such, he was deeply involved in legislative affairs. One of the first acts of Louis-Philippe in constructing his cabinet was to appoint the rather conservative Casimir Perier as the premier of that body. Perier, a banker, was instrumental in shutting down many of the Republican secret societies and labor unions that had formed during the early years of the regime. In addition, he oversaw the dismemberment of the National Guard after it proved too supportive of radical ideologies. He performed all of these actions, of course, with royal approval. He was once quoted as saying that the source of French misery was the belief that there had been a revolution. "No Monsieur," he said to another minister, "there has not been a revolution: there is simply a change at the head of state."

Further expressions of this conservative trend came under the supervision of Perier and the then Minister of the Interior, François Guizot. The regime acknowledged early on that radicalism and republicanism threatened it, undermining its laissez-faire policies. Thus, the Monarchy declared the very term republican illegal in 1834. Guizot shut down republican clubs and disbanded republican publications. Republicans within the cabinet, like the banker Dupont, were all but excluded by Perier and his conservative clique. Distrusting the sole National Guard, Louis-Philippe increased the size of the army and reformed it in order to ensure its loyalty to the government.

Though two factions always persisted in the cabinet, split between liberal conservatives like Guizot (le parti de la Résistance, the Party of Resistance) and liberal reformers like the aforementioned journalist Adolphe Thiers (le parti du Mouvement, the Party of Movement), the latter never gained prominence. After Perier came Count Molé, another conservative. After Molé came Thiers, a reformer later sacked by Louis-Philippe after attempting to pursue an aggressive foreign policy. After Thiers came the conservative Guizot. In particular, the Guizot administration was marked by increasingly authoritarian crackdowns on republicanism and dissent, and an increasingly pro-business policy. This policy included protective tariffs that defended the status quo and enriched French businessmen. Guizot's government granted railway and mining contracts to the bourgeois supporters of the government, and even contributed some of the start-up costs. As workers under these policies had no legal right to assemble, unionize, or petition the government for increased pay or decreased hours, the July Monarchy under Perier, Molé, and Guizot generally proved detrimental to the lower classes. In fact, Guizot's advice to those who were disenfranchised by the tax-based electoral requirements was simply "enrichissez-vous" (enrich yourselves).

Background

Following the ouster of Napoléon Bonaparte in 1814, the Allies restored the Bourbon Dynasty to the French throne. The ensuing period, the Bourbon Restoration, was characterized by conservative reaction and the re-establishment of the Roman Catholic Church as a power in French politics. The relatively liberal Comte de Provence, brother of the deposed-and-executed Louis XVI, ruled as Louis XVIII from 1814–1824 and was succeeded by his more conservative younger brother, the former Comte d'Artois, ruling as Charles X from 1824.

Despite the return of the House of Bourbon to power, France was much changed from the era of the ancien régime. The egalitarianism and liberalism of the revolutionaries remained an important force and the autocracy and hierarchy of the earlier era could not be fully restored. Economic changes, which had been underway long before the revolution, had progressed further during the years of turmoil and were firmly entrenched by 1815. These changes had seen power shift from the noble landowners to the urban merchants. The administrative reforms of Napoleon, such as the Napoleonic Code and efficient bureaucracy, also remained in place. These changes produced a unified central government that was fiscally sound and had much control over all areas of French life, a sharp difference from the complicated mix of feudal and absolutist traditions and institutions of pre-Revolutionary Bourbons.

Louis XVIII, for the most part, accepted that much had changed. However, he was pushed on his right by the Ultra-royalists, led by the comte de Villèle, who condemned the doctrinaires' attempt to reconcile the Revolution with the monarchy through a constitutional monarchy. Instead, the Chambre introuvable, elected in 1815, first banished all Conventionnels who had voted for Louis XVI's death and then passed similar reactionary laws. Louis XVIII was forced to dissolve this Chamber, dominated by the Ultras, in 1816, fearing a popular uprising. The liberals thus governed until the 1820 assassination of the duc de Berry, nephew of the king and known supporter of the Ultras, which brought Villèle's Ultras back to power (vote of the Anti-Sacrilege Act in 1825, and of the loi sur le milliard des émigrés, Act on the émigrés' billions). His brother Charles X, however, took a far more conservative approach. He attempted to compensate the aristocrats for what they had lost in the revolution, curbed the freedom of the press, and reasserted the power of the Church. In 1830 the discontent caused by these changes and Charles' authoritarian nomination of the Ultra prince de Polignac as minister culminated in an uprising in the streets of Paris, known as the 1830 July Revolution. Charles was forced to flee and Louis-Philippe d'Orléans, a member of the Orléans branch of the family, and son of Philippe Égalité who had voted the death of his cousin Louis XVI, ascended the throne. Louis-Philippe ruled, not as "King of France" but as "King of the French" (an evocative difference for contemporaries).

Initial period (August 1830 – November 1830)

The symbolic establishment of the new regime

On 7 August 1830, the 1814 Charter was revised. The preamble reviving the Ancien Régime was suppressed, and the King of France became the "King of the French", (also known as the "Citizen King") establishing the principle of national sovereignty over the principle of the divine right. The new Charter was a compromise between the Doctrinaires opposition to Charles X and the Republicans. Laws enforcing Catholicism and censorship were repealed and the revolutionary tricolor flag re-established.

Louis-Philippe pledged his oath to the 1830 Charter on 9 August setting up the beginnings of the July Monarchy. Two days later, the first cabinet was formed, gathering the Constitutionalist opposition to Charles X, including Casimir Perier, the banker Jacques Laffitte, Count Molé, the duke of Broglie, François Guizot, etc. The new government's first aim was to restore public order, while at the same time appearing to acclaim the revolutionary forces which had just triumphed. Assisted by the people of Paris in overthrowing the Legitimists, the Orleanist bourgeoisie had to establish its new order.

Louis-Philippe decided on 13 August 1830 to adopt the arms of the House of Orléans as state symbols. Reviewing a parade of the Parisian National Guard on 29 August which acclaimed the adoption, he exclaimed to its leader, Lafayette: "This is worth more to me than coronation at Reims!".[2] The new regime then decided on 11 October that all people injured during the revolution (500 orphans, 500 widows and 3,850 people injured) would be given financial compensation and presented a draft law indemnifying them in the amount of 7 million francs, also creating a commemorative medal for the July Revolutionaries.

Ministers lost their honorifics of Monseigneur and Excellence and became simply Monsieur le ministre. The new king's older son, Ferdinand-Philippe, was given the title of duke of Orléans and Prince Royal, while his daughters and his sister, Adélaïde d'Orléans, were named princesses of Orléans – and not of France, since there was no longer any "King of France" nor "House of France."

Unpopular laws passed during the Restoration were repealed, including the 1816 amnesty law which had banished the regicides – with the exception of article 4, concerning the Bonaparte family. The Church of Sainte-Geneviève was once again returned to its functions as a secular building, named the Panthéon. Various budget restrictions were imposed on the Catholic Church, while the 1825 Anti-Sacrilege Act which envisioned death penalties for sacrilege was repealed.

A permanent disorder

Civil unrest continued for three months, supported by the left-wing press. Louis-Philippe's government was not able to put an end to it, mostly because the National Guard was headed by one of the Republican leaders, the marquis de La Fayette, who advocated a "popular throne surrounded by Republican institutions." The Republicans then gathered themselves in popular clubs, in the tradition established by the 1789 Revolution. Some of those were fronts for secret societies (for example, the Blanquist Société des Amis du Peuple), which sought political and social reforms, or the execution of Charles X's ministers (Jules de Polignac, Jean de Chantelauze, the Count de Peyronnet and the Martial de Guernon-Ranville). Strikes and demonstrations were permanent.[3]

In order to stabilise the economy and finally secure public order, in the autumn of 1830 the government had the Assembly vote a credit of 5 million francs to subsidize public works, mostly roads. Then, to prevent bankruptcies and the increase of unemployment, especially in Paris, the government issued a guarantee for firms encountering difficulties, granting them 60 million francs. These subsidies mainly went into the pockets of big entrepreneurs aligned with the new regime, such as the printer Firmin Didot.

The death of the Prince of Condé on 27 August 1830, who was found hanged, caused the first scandal of the July Monarchy. Without proof, the Legitimists quickly accused Louis-Philippe and the Queen Marie-Amélie of having assassinated the ultra-royalist Prince, with the alleged motive of allowing their son, the duc d'Aumale, to get his hands on his fortune. It is however commonly accepted that the Prince died as a result of sex games with his mistress, the baroness de Feuchères.

Purge of the Legitimists

Meanwhile, the government expelled from the administration all Legitimist supporters who refused to pledge allegiance to the new regime, leading to the return to political affairs of most of the personnel of the First Empire, who had themselves been expelled during the Second Restoration. This renewal of political and administrative staff was humorously illustrated by a vaudeville of Jean-François Bayard.[4] The Minister of the Interior, Guizot, re-appointed the entire prefectoral administration and the mayors of large cities. The Minister of Justice, Dupont de l'Eure, assisted by his secretary general, Mérilhou, dismissed most of the public prosecutors. In the Army, the General de Bourmont, a follower of Charles X who was commanding the invasion of Algeria, was replaced by Bertrand Clauzel. Generals, ambassadors, plenipotentiary ministers and half of the Conseil d'État were replaced. In the Chamber of Deputies, a quarter of the seats (119) were submitted to a new election in October, leading to the defeat of the Legitimists.

In sociological terms, however, this renewal of political figures did not mark any great change of elites; land-owners, civil servants and liberal professions continued to dominate the state of affairs, leading the historian David H. Pinkney to deny any claim of a "new regime of a grande bourgeoisie".[5] Historian Guy Antonetti also underscores the similar sociological membership of the new elites, the main difference residing in the "substitution, inside the same social group, of the followers of a mentality which favoured the spirit of 1789 for those who were opposed to it: socially similar, ideologically different. 1830 was only a change of team on the same side, and not a change of sides.[6]

The "Resistance" and the "Movement"

Although some voices began to push for the closure of the Republican clubs, which fomented revolutionary agitation, the Minister of Justice, Dupont de l'Eure, and the Parisian public prosecutor, Bernard, both Republicans, refused to prosecute revolutionary associations (although the French law prohibited meetings of more than 20 persons).

However, on 25 September 1830, the Minister of Interior Guizot responded to a deputy's question on the subject by stigmatizing the "revolutionary state", which he conflated with chaos, to which he opposed the "Glorious Revolution".[7] Two political currents thereafter made their appearance, and would structure political life under the July Monarchy: the Movement Party and the Resistance Party. The first was reformist and in favor of support to the nationalists who were trying, all over of Europe, to shake the grip of the various Empires in order to create nation-states. Its mouthpiece was Le National. The second was conservative and supported peace with European monarchs, and had as mouthpiece Le Journal des débats.

The trial of Charles X's ministers, arrested in August 1830 while they were fleeing, became the major political issue. The left demanded their heads, but this was opposed by Louis-Philippe, who feared a spiral of violence and the renewal of revolutionary Terror. Thus, on 27 September 1830 the Chamber of Deputies passed a resolution charging the former ministers, but at the same time, in an address to king Louis-Philippe on 8 October, invited him to present a draft law repealing the death penalty, at least for political crimes. This in turn provoked popular discontent on 17 and 18 October, with the masses marching on the Fort of Vincennes where the ministers were detained.

Following these riots, Interior Minister Guizot requested the resignation of the prefect of the Seine, Odilon Barrot, who had criticized the parliamentarians' address to the king. Supported by Victor de Broglie, Guizot considered that an important civil servant could not criticize an act of the Chamber of Deputies, particularly when it had been approved by the King and his government. Dupont de l'Eure took Barrot's side, threatening to resign if the King disavowed him. The banker Laffitte, one of the main figures of the Parti du mouvement, thereupon put himself forward to coordinate the ministers with the title of "President of the Council." This immediately led Broglie and Guizot, of the Parti de l'Ordre, to resign, followed by Casimir Perier, André Dupin, the Count Molé and Joseph-Dominique Louis. Confronted to the Parti de l'Ordre's defeat, Louis-Philippe decided to put Laffitte to trial, hoping that the exercise of power would discredit him. He thus called him to form a new government on 2 November 1830.

The Laffitte government (2 November 1830 – 13 March 1831)

Although Louis-Philippe strongly disagreed with the banker Laffitte and secretly pledged to the duke of Broglie that he would not support him at all, the new President of the Council was tricked into trusting his king.

The trial of Charles X's former ministers took place from 15 to 21 December 1830 before the Chamber of Peers, surrounded by rioters demanding their death. They were finally sentenced to life detention, accompanied by civil death for Polignac. La Fayette's National Guard maintained public order in Paris, affirming itself as the bourgeois watchdog of the new regime, while the new Interior Minister, Camille de Montalivet, kept the ministers safe by detaining them in the fort of Vincennes.

But by demonstrating the National Guard's importance, La Fayette had made his position delicate, and he was quickly forced to resign. This led to the Minister of Justice Dupont de l'Eure's resignation. In order to avoid exclusive dependence on the National Guard, the "Citizen King" charged Marshal Soult, the new Minister of War, with reorganizing the Army. In February 1831, Soult presented his project, aiming to increase the military's effectiveness. Among other reforms, the project included the 9 March 1831 law creating the Foreign Legion.

In the meantime, the government enacted various reforms demanded by the Parti du Mouvement, which had been set out in the Charter (art. 69). The 21 March 1831 law on municipal councils reestablished the principle of election and enlarged the electorate (founded on census suffrage) which was thus increased tenfold in comparison with the legislative elections (approximately 2 to 3 million electors from a total population of 32,6 million). The 22 March 1831 law re-organized the National Guard; the 19 April 1831 law, voted after two months of debate in Parliament and promulgated after Laffitte's downfall, decreased the electoral income level from 300 to 200 Francs and the level for eligibility from 1,000 to 500 Francs. The number of voters thereby increased from less than 100,000 to 166,000: one Frenchman in 170 possessed the right to vote, and the number of constituencies rose from 430 to 459.

The February 1831 riots

Despite these reforms, which targeted the bourgeoisie rather than the people, Paris was once again rocked by riots on 14 and 15 February 1831, leading to Laffitte's downfall. The immediate cause of the riots was a funeral service organized by the Legitimists at Saint-Germains l'Auxerrois Church in memory of the ultra-royalist duke of Berry, assassinated in 1820. The commemoration turned into a political demonstration in favour of the count of Chambord, Legitimist pretender to the throne. Seeing in this celebration an intolerable provocation, the Republican rioters ransacked the church two days in a row, before turning on other churches. The revolutionary movement spread to other cities.

Confronted with renewed unrest, the government abstained from any strong repression. The prefect of the Seine Odilon Barrot, the prefect of police Jean-Jacques Baude, and the new commandant of the National Guard, General Georges Mouton, remained passive, triggering Guizot's indignation, as well as the Republican Armand Carrel's criticisms against the alleged demagogy of the government.[8] Far from suppressing the crowds, the government had the Archbishop of Paris Mgr. de Quélen arrested, as well as charging the friar of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois and other priests, along with some other monarchists, with having provoked the masses.

In a gesture of appeasement, Laffitte, supported by the Prince Royal Ferdinand-Philippe, duke of Orléans, proposed to the king that he remove the fleur-de-lys, symbol of the Ancien Régime, from the state seal. With obvious displeasure, Louis-Philippe finally signed the 16 February 1831 ordinance substituting for the arms of the House of Orléans a shield with an open book, on which could be read "Charte de 1830". The fleur-de-lys, was also removed from public buildings, etc. This new defeat of the king sealed Laffitte's fate.

On 19 February 1831, Guizot verbally attacked Laffitte in the Chamber of Deputies, daring him to dissolve the Chamber and present himself before the electors. Laffitte accepted, but the king, who was the only one entitled to dissolve the Chamber, preferred to wait a few days more. In the meanwhile, the prefect of the Seine Odilon Barrot was replaced by Taillepied de Bondy at Montalivet's request, and the prefect of police Jean-Jacques Baude by Vivien de Goubert. To make matters worse, in this insurrectionary climate, the economic situation was fairly bad.

Louis-Philippe finally tricked Laffitte into resigning by having his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Horace Sébastiani, pass him a note written by the French ambassador to Vienna, Marshal Maison, and which had arrived in Paris on 4 March 1831, which announced an imminent Austrian intervention in Italy. Learning of this note in Le Moniteur of 8 March, Laffitte requested an immediate explanations from Sébastiani, who replied that he had followed royal orders. After a meeting with the king, Laffitte submitted to the Council of Ministers a belligerent program, and was subsequently disavowed, forcing him to resign. Most of his ministers had already negotiated their positions in the forthcoming government.

The Casimir Perier government (13 March 1831 – 16 May 1832)

Having succeeded in outdoing the Parti du Mouvement, the "Citizen King" called to power the Parti de la Résistance. However, Louis-Philippe was not really much more comfortable with one side than with the other, being closer to the center. Furthermore, he felt no sympathy for its leader, the banker Casimir Perier, who replaced Laffitte on 13 March 1831 as head of the government. His aim was more to re-establish order in the country, letting the Parti de la Résistance assume responsibility for unpopular measures.

Perier, however, managed to impose his conditions on the king, including the pre-eminence of the President of the Council over other ministers, and his right to call cabinet councils outside of the actual presence of the king. Furthermore, Casimir Perier secured agreement that the liberal Prince Royal, Ferdinand-Philippe d'Orléans, would cease to participate to the Council of Ministers. Despite this, Perier valued the king's prestige, calling on him, on 21 September 1831, to move from his family residence, the Palais-Royal, to the royal palace, the Tuileries.

The banker Perier established the new government's principles on 18 March 1831: ministerial solidarity and the authority of the government over the administration: "the principle of the July Revolution... is not insurrection... it is resistance to the aggression the power"[9] and, internationally, "a pacific attitude and the respect of the non-intervention principle." The vast majority of the Chamber applauded the new government and granted him a comfortable majority. Perier harnessed the support of the cabinet through oaths of solidarity and strict discipline for dissenters. He excluded reformers from official discourse, and abandoned the regime's unofficial policy of mediating in labor disputes in favor of a strict laissez-faire policy that favored employers.

Civil unrest (Canut Revolt) and repression

On 14 March 1831, on the initiative of a patriotic society created by the mayor of Metz, Jean-Baptiste Bouchotte, the opposition's press launched a campaign to gather funds to create a national association aimed at struggling against any Bourbon Restoration and the risks of foreign invasion. All the major figures of the Republican Left (La Fayette, Dupont de l'Eure, Jean Maximilien Lamarque, Odilon Barrot, etc.) supported it. Local committees were created all over France, leading the new president of the Council, Casimir Perier, to issue a circular prohibiting civil servants from membership of this association, which he accused of challenging the state itself by implicitly accusing it of not fulfilling its proper duties.

In the beginning of April 1831, the government took some unpopular measures, forcing several important personalities to resign: Odilon Barrot was dismissed from the Council of State, General Lamarque's military command suppressed, Bouchotte and the Marquis de Laborde forced to resign. When on 15 April 1831 the Cour d'assises acquitted several young Republicans (Godefroy Cavaignac, Joseph Guinard and Audry de Puyraveau's son), mostly officers of the National Guard who had been arrested during the December 1830 troubles following the trial of Charles X's ministers, new riots acclaimed the news on 15–16 April. But Perier, implementing the 10 April 1831 law outlawing public meetings, used the military as well as the National Guard to dissolve the crowds. In May, the government used fire hoses as crowd control techniques for the first time.

Another riot, started on the rue Saint-Denis on 14 June 1831, degenerated into an open battle against the National Guard, assisted by the Dragoons and the infantry. The riots continued on 15 and 16 June.

The major unrest, however, took place in Lyon with the Canuts Revolt, started on 21 November 1831, and during which parts of the National Guard took the demonstrators' side. In two days, the Canuts took control of the city and expelled General Roguet and the mayor Victor Prunelle. On 25 November Casimir Perier announced to the Chamber of Deputies that Marshal Soult, assisted by the Prince Royal, would immediately march on Lyon with 20,000 men. They entered the city on 3 December re-establishing order without any bloodshed.

Civil unrest, however, continued, and not only in Paris. On 11 March 1832, sedition exploded in Grenoble during the carnival. The prefect had canceled the festivities after a grotesque mask of Louis-Philippe had been displayed, leading to popular demonstrations. The prefect then tried to have the National Guard disperse the crowd, but the latter refused to go, forcing him to call on the army. The 35th regiment of infantry (infanterie de ligne) obeyed the orders, but this in turn led the population to demand their expulsion from the city. This was done on 15 March and the 35th regiment was replaced by the 6th regiment, from Lyon. When Casimir Perier learnt the news, he dissolved the National Guard of Grenoble and immediately recalled the 35th regiment to the city.

Beside this continuing unrest, in every province, Dauphiné, Picardy, in Carcassonne, Alsace, etc., various Republican conspiracies threatened the government (conspiracy of the Tours de Notre-Dame in January 1832, of the rue des Prouvaires in February 1832, etc.) Even the trials of suspects were seized on by the Republicans as an opportunity to address the people: at the trial of the Blanquist Société des Amis du peuple in January 1832, Raspail harshly criticized the king while Auguste Blanqui gave free vein to his socialist ideas. All of the accused denounced the government's tyranny, the incredibly high cost of Louis-Philippe's civil list, police persecutions, etc. The omnipresence of the French police, organized during the French First Empire by Fouché, was depicted by the Legitimist writer Balzac in Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes. The strength of the opposition led the Prince Royal to shift his view somewhat further to the right.

Legislative elections of 1831

In the second half of May 1831, Louis-Philippe, accompanied by Marshal Soult, started an official visit to Normandy and Picardy, where he was well received. From 6 June to 1 July 1831, he traveled in the east, where there was stronger Republican and Bonapartist activity, along with his two elder sons, the Prince Royal and the duke of Nemours, as well as with the comte d'Argout. The king stopped in Meaux, Château-Thierry, Châlons-sur-Marne (renamed Châlons-en-Champagne in 1998), Valmy, Verdun and Metz. There, in the name of the municipal council, the mayor made a very political speech in which he expressed the wish to have peerages abolished, adding that France should intervene in Poland to assist the November Uprising against Russia. Louis-Philippe flatly rejected all of these aspirations, stating that the municipal councils and the National Guard had no standing in such matters. The king continued his visit to Nancy, Lunéville, Strasbourg, Colmar, Mulhouse, Besançon and Troyes, and his visits were, on the whole, occasions to re-affirm his authority.

Louis-Philippe decided in the château de Saint-Cloud, on 31 May 1831, to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies, fixing legislative elections for 5 July 1831. However, he signed another ordinance on 23 June in Colmar in order to have the elections put back to 23 July 1831, so as to avoid the risk of Republican agitation during the commemorations of the July Revolution. The general election of 1831 took place without incident, according to the new electoral law of 19 April 1831. However, the results disappointed the king and the president of the Council, Perier: more than half of the outgoing deputies were re-elected, and their political positions were unknown. The Legitimists obtained 104 seats, the Orleanist Liberals 282 and the Republicans 73.

On 23 July 1831, the king set out Casimir Perier's program in the speech from the Throne: strict application of the Charter at home and strict defense of the interests of France and its independence abroad.

The deputies in the chamber then voted for their President, electing Baron Girod de l'Ain, the government's candidate, on the second round. He gained 181 votes to the banker Laffitte's 176. But Dupont de l'Eure gained the first vice presidency with 182 voices out of a total of 344, defeating the government's candidate, André Dupin, who had only 153 votes. Casimir Perier, who considered that his parliamentary majority was not strong enough, decided to resign.

Louis-Philippe thereafter turned towards Odilon Barrot, who refused to assume governmental responsibilities, pointing out that he had only a hundred deputies in the Chamber. However, during the 2 and 2 August 1831 elections of questeurs and secretaries, the Chamber elected mostly government candidates such as André Dupin and Benjamin Delessert, who obtained a strong majority against a far-left candidate, Eusèbe de Salverte. Finally, William I of the Netherlands's decision to invade Belgium – the Belgian Revolution had taken place the preceding year – on 2 August 1831, constrained Casimir Perier to remain in power in order to respond to the Belgians' request for help.

During the parliamentary debates concerning France's imminent intervention in Belgium, several deputies, led by baron Bignon, unsuccessfully requested similar intervention to support Polish independence. However, at the domestic level, Casimir Perier decided to back down before the dominant opposition, and satisfied an old demand of the Left by abolishing hereditary peerages. Finally, the 2 March 1832 law on Louis-Philippe's civil list fixed it at 12 million francs a year, and one million for the Prince Royal, the duke of Orléans. The 28 April 1832 law, named after the Justice Minister Félix Barthe, reformed the 1810 Penal Code and the Code d'instruction criminelle.

The 1832 cholera epidemic

The cholera pandemic that originated in India in 1815 reached Paris around 20 March 1832 and killed more than 13,000 people in April. The pandemic would last until September 1832, killing in total 100,000 in France, with 20,000 in Paris alone.[10] The disease, the origins of which were unknown at the time, provoked a popular panic. The people of Paris suspected poisoners, while scavengers and beggars revolted against the authoritarian measures of public health.

According to the 20th-century historian and philosopher Michel Foucault, the cholera outbreak was first fought by what he called "social medicine", which focused on flux, circulation of air, location of cemeteries, etc. All of these concerns, born of the miasma theory of disease, were thus concerned with urbanist concerns of the management of populations.

Cholera also struck the royal princess Madame Adélaïde, as well as d'Argout and Guizot. Casimir Perier, who on 1 April 1832 visited the patients at the Hôtel-Dieu with the Prince Royal, contracted the disease. He resigned his ministerial activities before dying of cholera on 16 May 1832.

The consolidation of the regime (1832–1835)

King Louis-Philippe was not unhappy to see Casimir Perier withdraw from the political scene, as he complained that Perier took all the credit for the government's policy successes, while he himself had to assume all the criticism for its failures.[11] The "Citizen King" was therefore not in any hurry to find a new President of the Council, all the more since the Parliament was in recess and that the troubled situation demanded swift and energetic measures.

Indeed, the regime was being attacked on all sides. The Legitimist duchess of Berry attempted an uprising in spring 1832 in Provence and Vendée, a stronghold of the ultra-royalists, while the Republicans headed an insurrection in Paris on 5 June 1832, on the occasion of the funeral of one of their leaders, General Lamarque, also struck dead by the cholera. General Mouton crushed the rebellion, killing 800. The scene was later depicted by Victor Hugo in Les Misérables.

This double victory, over both the Carlists Legitimists and the Republicans, was a success for the regime.[12] Furthermore, the death of the duke of Reichstadt (Napoléon II) on 22 July 1832, in Vienna, marked another defeat for the Bonapartist opposition.

Finally, Louis-Philippe married his elder daughter, Louise d'Orléans, to the new king of the Belgians, Leopold I, on the anniversary of the establishment of the July Monarchy (9 August). Since the archbishop of Paris Quélen, a Legitimist, refused to celebrate this mixed marriage between a Catholic and a Lutheran, the wedding took place in the château de Compiègne. This royal alliance strengthened Louis-Philippe's position abroad.

First Soult government

Louis-Philippe called a trusted man, Marshal Soult, to the Presidency of the Council in October 1832. Soult was supported by a triumvirate composed of the main politicians of that time: Adolphe Thiers, the duke de Broglie and François Guizot. The conservative Journal des débats spoke of a "coalition of all talents",[13] while the King of the French would eventually speak, with obvious disappointment, of a "Casimir Perier in three persons." In a circular addressed to the high civil servants and military officers, the new President of the Council, Soult, stated that he would explicitly follow the policies of Perier ("order at home", "peace abroad") and denounced both the Legitimist right-wing opposition and the Republican left-wing opposition.

The new Minister of Interior, Adolphe Thiers, had his first success on 7 November 1832 with the arrest in Nantes of the rebellious duchess of Berry, who was detained in the citadel of Blaye. The duchess was then expelled to Italy on 8 June 1833.

The opening of the parliamentary session on 19 November 1832, was a success for the regime. The governmental candidate, André Dupin, was easily elected on the first round as President of the Chamber, with 234 votes against 136 for the candidate of the opposition, Jacques Laffitte.

In Belgium, Marshal Gérard assisted the young Belgian monarchy with 70,000 men, taking back the citadel of Antwerp, which capitulated on 23 December 1832.

Strengthened by these recent successes, Louis-Philippe initiated two visits to the provinces, first into the north to meet with the victorious Marshal Gérard and his men, and then into Normandy, where Legitimist troubles continued, from August to September 1833. In order to conciliate public opinion, the members of the new government took some popular measures, such as a program of public works, leading to the completion of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, and the re-establishment, on 21 June 1833, of Napoleon I's statue on the Colonne Vendôme. The Minister of Public Instruction and Cults, François Guizot, had the famous law on primary education passed in June 1833, leading to the creation of an elementary school in each commune.

Finally, a ministerial change was enacted after the duke de Broglie's resignation on 1 April 1834. Broglie had found himself in a minority in the Chamber concerning the ratification of a treaty signed with the United States in 1831. This was a source of satisfaction for the king, as it removed from the triumvirate the individual he disliked the most.

April 1834 insurrections

The ministerial change coincided with the return of violent unrest in various cities of France. At the end of February 1834, a new law that subjected the activities of town criers to public authorization led to several days of confrontations with the police. Furthermore, the 10 April 1834 law, primarily aimed against the Republican Society of the Rights of Man (Société des Droits de l'Homme), envisioned a crack-down on non-authorized associations. On 9 April 1834, when the Chamber of Peers was to vote on the law, the Second Canut Revolt exploded in Lyon. The Minister of the Interior, Adolphe Thiers, decided to abandon the city to the insurgents, taking it back on 13 April with casualties of 100 to 200 dead on both sides.

The Republicans attempted to spread the insurrection to other cities, but failed in Marseille, Vienne, Poitiers and Châlons-sur-Marne. The threat was more serious in Grenoble and especially in Saint-Étienne on 11 April but finally public order was restored. The greater danger to the regime was, as often, in Paris. Expecting trouble, Thiers had concentrated 40,000 men there, who were visited by the king on 10 April. Furthermore, Thiers had made "preventive arrests" against the 150 main leaders of the Society of the Rights of Man (Société des Droits de l'Homme), and outlawed its mouthpiece, La Tribune des départements. Despite these measures, barricades were set up in the evening of 13 April 1834, leading to harsh repression, including a massacre of all the inhabitants (men, women, children and old people) of a house from where a shot had been fired. This incident was immortalized in a lithograph by Honoré Daumier.

To express their support for the monarchy, both Chambers gathered in the Palace of the Tuileries on 14 April. In a gesture of appeasement, Louis-Philippe cancelled his feast-day celebration on 1 May, and publicly announced that the sums that were to have been used for these festivities would be dedicated to the orphans, widows and injured. In the same time, he ordered Marshal Soult to publicise these events widely across France (the provinces being more conservative than Paris), to convince them of the "necessary increase in the Army.".[14]

More than 2,000 arrests were made following the riots, in particular in Paris and Lyon. The cases were referred to the Chamber of Peers, which, in accordance with art. 28 of the Charter of 1830, dealt with cases of conspiracy against state security (attentat contre la sûreté de l'État). The Republican movement was decapitated, so much that even the funerals of La Fayette on 20 May 1834, were quiet. As early as 13 May the Chamber of Deputies voted a credit of 14 million in order to increase the army to 360,000 men. Two days later, they also adopted a very repressive law on detention and use of military weapons.

Legislative elections of 1834

Louis-Philippe decided to seize the opportunity of dissolving the Chamber and organizing new elections, which were held on 21 June 1834. However, the results were not as favorable to him as expected: although the Republicans were almost eliminated, the Opposition retained around 150 seats (approximately 30 Legitimists, the rest being followers of Odilon Barrot, who was an Orleanist supporter of the regime, but headed the Parti du mouvement). Furthermore, in the ranks of the majority itself, composed of about 300 deputies, a new faction, the Tiers-Parti, led by André Dupin, could on some occasions defect from the majority and give its votes to the Left. On 31 July the new Chamber re-elected Dupin as President of the Chamber with 247 votes against 33 for Jacques Laffitte and 24 for Pierre-Paul Royer-Collard. Furthermore, a large majority (256 against 39) voted an ambiguous address to the king which, although polite, did not abstain from criticizing him. The latter immediately decided, on 16 August 1834, to prorogue Parliament until the end of the year.

Short-lived governments (July 1834 – February 1835)

Thiers and Guizot, who dominated the triumvirate, decided to get rid of Marshal Soult, who was appreciated by the king for his compliant attitude. Seizing the opportunity of an incident concerning the French possessions in Algeria, they pushed Soult to resign on 18 July 1834. He was replaced by Marshal Gérard, with the other ministers remaining in place. Gérard, however, was forced to resign in turn, on 29 October 1834, over the question of an amnesty for the 2,000 prisoners detained in April. Louis-Philippe, the Doctrinaires (including Guizot and Thiers) and the core of the government opposed the amnesty, but the Tiers Parti managed to convince Gérard to announce it, underscoring the logistical difficulties in organizing such a large trial before the Chamber of Peers.

Gérard's resignation opened up a four-month ministerial crisis, until Louis-Philippe finally assembled a government entirely from the Tiers Parti. However, after André Dupin's refusal to assume its presidency, the king made the mistake of calling, on 10 November 1834, a figure from the First Empire, the duc de Bassano, to head his government. The latter, crippled with debts, became the object of public ridicule after his creditors decided to seize his ministerial salary. Alarmed, all the ministers decided to resign, three days later, without even advising Bassano, whose government became known as the "Three Days Ministry." On 18 November 1834, Louis-Philippe called Marshal Mortier, duke of Trévise, to the Presidency, and the latter formed exactly the same government as Bassano. This crisis made the Tiers Parti ridiculous while the Doctrinaires triumphed.

On 1 December 1834, Mortier's government decided to submit a motion of confidence to the Parliament, obtaining a clear majority (184 votes to 117). Despite this, Mortier had to resign two months later, on 20 February 1835, officially for health reasons. The opposition had denounced a government without a leader, accusing Mortier of being Louis-Philippe's puppet. The same phrase that Thiers had spoken in opposition to Charles X, "the king reigns but does not rule" (le roi règne mais ne gouverne pas), was now addressed to the "Citizen King".

Evolution towards parliamentarianism (1835–1840)

The polemics which led to Marshal Mortier's resignation, fuelled by monarchists such as Baron Massias and the Count of Roederer, all turned around the question of parliamentary prerogative. On the one hand, Louis-Philippe wanted to be able to follow his own policy, in particular in "reserved domains" such as military affairs or diplomacy. As the head of state, he also wanted to be able to lead the government, if need be by bypassing the President of the Council. On the other hand, a number of the deputies stated that the ministers needed a leader commanding a parliamentary majority, and thus wanted to continue the evolution towards parliamentarism which had only been sketched out in the Charter of 1830. The Charter did not include any mechanism for the political accountability of ministers towards the Chamber (confidence motions or for censorship motions). Furthermore, the function of the President of the Council itself was not even set out in the Charter.

The Broglie ministry (March 1835 – February 1836)

In this context, the deputies decided to support Victor de Broglie as head of the government, mainly because he was the king's least preferred choice, as Louis-Philippe disliked both his anglophilia and his independence. After a three-week ministerial crisis, during which the "Citizen King" successively called on count Molé, André Dupin, Marshal Soult, General Sébastiani and Gérard, he was finally forced to rely on the duc de Broglie and to accept his conditions, which were close to those imposed before by Casimir Perier.

As in the first Soult government, the new cabinet rested on the triumvirate Broglie (Foreign affairs) – Guizot (Public instruction) – Thiers (Interior). Broglie's first act was to take a personal revenge on the Chamber by having it ratify (by 289 votes against 137) the 4 July 1831 treaty with the United States, something which the deputies had refused him in 1834. He also obtained a large majority on the debate the secret funds, which worked as an unofficial motion of confidence (256 voices against 129).

Trial of the April insurgents

Broglie's most important task was the trial of the April insurgents, which began on 5 May 1835 before the Chamber of Peers. The Peers finally convicted only 164 detainees on the 2,000 prisoners, of whom 43 were judged in absentia. Those defendants who were present for their trial introduced a great many procedural delays, and attempted by all means to transform the trial into a platform for Republicanism. On 12 July 1835, some of them, including the main leaders of the Parisian insurrection, escaped from the Prison of Sainte-Pélagie through an underground tunnel. The Court of Peers delivered its sentence on the insurgees of Lyon on 13 August 1835, and on the other defendants in December 1835 and January 1836. The sentences were rather mild: a few condemnations to deportation, many short prison sentences and some acquittals.

The Fieschi attentat (28 July 1835)

.jpg)

Against their hopes, the trial finally turned to the Republicans' disadvantage, by giving them a radical image which reminded the public opinion of the excesses of Jacobinism and frightened the bourgeois. The Fieschi attentat of July 1835, which took place on Paris during a review of the National Guard by Louis-Philippe for the commemorations of the July Revolution, further scared the notables.

On the boulevard du Temple, near the Place de la République, a volley gun composed of twenty-five gun barrels mounted on a wooden frame was fired on the king from the upstairs window of a house. The King was only slightly injured, while his sons, Ferdinand-Philippe, duc d'Orléans, Louis-Charles d'Orléans, duc de Nemours and François d'Orléans, prince de Joinville, escaped unharmed. However, Marshal Mortier and ten other persons were killed, while tens were injured (among which seven died in the following days).

The conspirators, the adventurer Giuseppe Fieschi and two Republicans (Pierre Morey and Théodore Pépin) members of the Society of Human Rights, were arrested in September 1835. Judged before the Court of Peers, they were sentenced to death and guillotined on 19 February 1836.

The September 1835 laws

The Fieschi attentat shocked the bourgeoisie and most of France, which was generally more conservative than the people of Paris. The Republicans were discredited in the country, and public opinion was ready for strong measures against them.

The first law reinforced the powers of the president of the Cour d'assises and of the public prosecutor against those accused of rebellion, possession of prohibited weapons or attempted insurrection. It was adopted on 13 August 1835, by 212 votes to 72.

The second law reformed the procedure before the juries of the Assizes. The existing 4 March 1831 law confined the determination of guilt or innocence to the juries, excluding the professional magistrates belonging to the Cour d'assises, and required a 2/3 majority (8 votes to 4) for a guilty verdict. The new law changed that to a simple majority (7 against 5), and was adopted on 20 August 1835 by 224 votes to 149.

The third law restricted freedom of press, and provoked passionate debates. It aimed at outlawing discussions concerning the king, the dynasty and constitutional monarchy, as it was alleged that these had prepared the ground for the Fieschi attentat. Despite a strong opposition to the draft, the law was approved on 29 August 1835 by 226 votes to 153.

The final consolidation of the regime

These three laws were simultaneously promulgated on 9 September 1835, and marked the final success of the policy of Résistance pursued against the Republicans since Casimir Perier. The July Monarchy was thereafter sure of its ground, with discussions concerning its legitimacy being completely outlawed. The Opposition could now only discuss the interpretation of the Charter and advocate an evolution towards parliamentarianism. Demands for the enlargement of the electoral base became more frequent, however, in 1840, leading to the re-appearance of Republican Opposition through the claim to universal suffrage.

The Broglie ministry, however, finally fell on a question concerning the public debt. The Minister of Finance, Georges Humann, announced on 14 January 1836 his intention to reduce the interest on government bonds in order to lighten the public debt, a very unpopular measure among the supporters of the regime, since bond interest was a fundamental component of the bourgeoisie's wealth. Therefore, the Council of Ministers immediately disavowed Humann, while the Duke de Broglie explained to the Chamber that his proposal was not supported by the government. However, his tone was judged insulting by the deputies, and one of them, the banker Alexandre Goüin, immediately proposed a draft law concerning bonds himself. On 5 February 1836, a narrow majority of deputies (194 against 192) decided to continue the examination of the draft, thus disavowing Broglie's cabinet. The government immediately resigned: for the first time, a cabinet had fallen after having been put in a minority before the Chamber of Deputies, a sure victory of parliamentarianism.

The first Thiers government (February–September 1836)

Louis-Philippe then decided to pretend to play the parliamentary card, with the secret intention of neutralizing it. He took advantage of the ministerial crisis to get rid of the Doctrinaires (Broglie and Guizot), invited some Tiers Parti politicians to give an illusion of an opening to the Left, and finally called on Adolphe Thiers on 22 February 1836, in an attempt to convince him to distances himself from the liberal Doctrinaires, and also to use up his legitimacy in government, until the time came to call on Count Molé, whom the king had decided a long time before to make his President of the Council. Louis-Philippe thus separated the center-right from the center-left, strategically attempting to dissolve the Tiers Parti, a dangerous game since this could also lead to the dissolving of the parliamentary majority itself and create endless ministerial crises. Furthermore, as the duc de Broglie himself warned him, when Thiers was eventually pushed out, he would shift decisively to the Left and transform himself in a particularly dangerous opponent.

In the Chamber, the debate on the secret funds, marked by a notable speech by Guizot and an evasive response by the Justice Minister, Sauzet, was concluded with a favorable vote for the government (251 votes to 99). On the other hand, the draft proposal on government bonds was easily postponed by the deputies on 22 March 1836, another sign that it had been only a pretext.

Thiers' motivations for accepting the position of head of the government and taking the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as well were to enable him to negotiate the Duc d'Orléans' wedding with an Austrian archduchess. Since the Fieschi attentat, Ferdinand-Philippe's wedding (he had just reached 25) had become an obsession of the king, and Thiers wanted to effect a spectacular reversion of alliances in Europe, as Choiseul had done before him. But Metternich and the archduchess Sophie of Bavaria, who dominated the court in Vienna, rejected an alliance with the House of Orléans, which they deemed too unstable.

Another attentat against Louis-Philippe, by Alibaud on 25 June 1836, justified their fears. These two setbacks upset Thiers. On 29 July 1836, the inauguration of the Arc de Triomphe, intended to be the scene of a ceremony of national concord, during which the July Monarchy would harness the glory of the Revolution and of the Empire, finally took place, quietly and unceremoniously, at seven in the morning and without the king being present.

To re-establish his popularity and in order to take his revenge on Austria, Thiers was considering a military intervention in Spain, requested by the Queen Regent Marie Christine de Bourbon who was confronted by the Carlist rebellion. But Louis-Philippe, advised by Talleyrand and Soult, strongly opposed the intervention, which led to Thiers's resignation. This new event, in which the government had fallen not because of parliament but because of a disagreement with the king on foreign policy, demonstrated that the evolution towards parliamentarianism was far from being assured.

The two Molé governments (September 1836 – March 1839)

Count Molé formed a new government on 6 September 1836, including the Doctrinaires Guizot, Tanneguy Duchâtel and Adrien de Gasparin. This new cabinet did not include any one of the 'Three Glorious', something the press immediately highlighted. Molé immediately took some humane measures in order to assure his popularity: the general adoption of small prison cells to avoid "mutual teaching of crime", abolition of chain gangs exposed to the public, and a royal pardon for 52 political prisoners (Legitimists and Republicans), in particular for Charles X' former ministers. On 25 October 1836, the inauguration of the Obelisk of Luxor (a gift from the viceroy of Egypt, Mehemet Ali) on the Place de la Concorde was the scene of a public ovation for the King.

1836 Bonapartist uprising

On 30 October 1836, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte attempted an uprising in Strasbourg, which was quickly put down and the Bonapartist prince and his accomplices were arrested on the same day. The king, wanting to avoid a public trial, and without legal proceedings, ordered that Louis-Napoléon be taken to Lorient where he was put on board the frigate L'Andromède, which sailed for the United States on 21 November. The other conspirators were brought before the Cour d'assises of Strasbourg, which acquitted them on 18 January 1837.

Loi de disjonction

Thereafter, on 24 January 1837, the Minister of War, General Simon Bernard (Baron), proposed a draft law – loi de disjonction – aimed, in case of insurrection, at separating civilians, who would be judged by the Cour d'assises, and non-civilians, who would be judged by a war council. The opposition adamantly rejected the proposal, and surprisingly managed to have the whole Chamber reject it, on 7 March 1837, by a very slim majority of 211 votes to 209.

However, Louis-Philippe decided to go against public expectation, and the logic of parliamentarianism, by maintaining the Molé government in place. But the government was deprived of any solid parliamentary majority, and thus paralyzed. For a month and a half, the king tried various ministerial combinations before forming a new government which included Camille de Montalivet, who was close to him, but which excluded Guizot, who had more and more difficulty working with Molé, who was once again confirmed as head of the government.

This new government was almost a provocation for the Chamber: not only was Molé retained, but de Salvandy, who had been in charge of the loi de disjonction, and Lacave-Laplagne, in charge of a draft law concerning the Belgian Queen's dowry – both having been rejected by the deputies – were also members of the new cabinet. The press spoke of a "Cabinet of the castle" or "Cabinet of lackeys", and all expected it to be short-lived.

The wedding of the Duke of Orléans

However, in his first speech, on 18 April 1837, Molé cut short his critics with the announcement of the future wedding of Ferdinand Philippe, Duke of Orléans (styled as the prince royal) with the Duchess Helene of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Taken by surprise, the deputies voted for the increase of the dowry of both the Duke of Orléans, which had been previously rejected, and the Queen of the Belgians.

After this promising beginning, in May Molé's government managed to secure Parliament's confidence during the debate on the secret funds, despite Odilon Barrot's attacks (250 votes to 112). An 8 May 1837 ordinance granted general amnesty to all political prisoners, while crucifixes were re-established in the courts, and the Church of Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois, closed since 1831, was authorized to renew religious activities. To demonstrate that public order had been restored, the king passed reviewed the National Guard on the Place de la Concorde. On 30 May 1837, the Duke of Orléans' wedding was celebrated at the château de Fontainebleau.

A few days later, on 10 June Louis-Philippe inaugurated the château de Versailles, the restoration of which, begun in 1833, was intended to establish a Museum of the History of France, dedicated to "all the glories of France". The king had closely followed and personally financed the project entrusted to the architect Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine. In a symbol of national reconciliation, the military glories of the Revolution and of the Empire, even those of the Restoration, were to sit side by side with those of the Ancien Régime.

The legislative elections of 4 November 1837

Molé's government seemed stable, helped by the return of economic prosperity. Therefore, the king and Molé decided, against the duc d'Orléans' advice, that the moment was auspicious for the dissolving of the Chamber, which was done on 3 October 1837. In order to influence the forthcoming elections, Louis-Philippe decided on the Constantine expedition in Algeria, a military success of General Valée and the duc de Nemours, second son of Louis-Philippe, who took Constantine on 13 October.

However, the 4 November 1837 elections did not deliver Louis-Philippe's hopes. Of a total of 459 deputies, only a plurality of 220 were supporters of the regime. About 20 Legitimists had been elected, and 30 Republicans. The centre-right (Doctrinaires) had approximately 30 deputies, the centre-left about twice that many, and the dynastic opposition (Odilon Barrot) 65. The Tiers parti had only about 15 deputies, and 30 more were undecided. Such a Chamber carried the risk of the formation of a heterogeneous coalition against the government.

As early as January 1838, the government was under great pressure, in particular from Charles Gauguier, over deputies who were also civil servants. On 9 January he accused the government of electoral manipulation in order to have loyal civil servants elected. Where there had been 178 in the preceding Chamber, there were now 191. Adolphe Thiers and his allies also defied the government, concerning Spanish affairs. However, with the help of the Doctrinaires, Molé obtained a favorable vote for the address to the king on 13 January 1838, with 216 votes to 116.

Molé's cabinet appeared to be taken hostage by the Doctrinaires, at the exact moment when Guizot was distancing himself from the President of the Council. All of Thiers' efforts would be thereafter focused on pushing the Doctrinaires away from the ministerial majority. During the vote on the secret funds, both Guizot, in the Chamber of Deputies, and the duc de Broglie, in the Chamber of Peers, criticized the cabinet, although both ultimately voted with the government.

On 10 May 1838, the deputies rejected the government's plan for railway development, after having finally agreed, a week earlier, the proposals on government bonds opposed by Molé. The Peers, however, supported Molé and rejected the initiative. On 20 June 1838, Molé succeeded in having the Assembly pass the 1839 budget before the parliamentary recess.

On the opening of the parliamentary session in December 1838, André Dupin was elected by a very slim majority (183 votes for 178 for Hippolyte Passy, the center-left candidate and adamant opponent of the "Castle cabinet") as President of the Chamber. A coalition, including Guizot, Thiers, Prosper Duvergier de Hauranne and Hippolyte Passy, had formed during summer, but it did not prevent the vote of a favorable address to the King (221 votes against 208).

The legislative elections of 2 March 1839

Confronted to such a slight and uncertain majority, Molé presented his resignation to the king on 22 January 1839. Louis-Philippe first attempted to refuse it, and then, approaching Marshal Soult, who was not initially persuaded, offered him the lead. Soult finally accepted after the funeral of the king's daughter, the duchesse de Württemberg, on the condition of moving promptly to new elections. During the electoral campaign, the left-wing opposition denounced what they termed a constitutional coup, comparing the 1837 and 1839 dissolutions to the consecutive dissolutions of Charles X in 1830. Thiers compared Molé to Polignac, one of Charles X's ministers.

The 2 March 1839 elections were a disappointment for the king, who lost two loyal deputies, while the coalition mustered 240 members (against only 199 for the government). Molé presented his resignation to the king on 8 March, which Louis-Philippe was forced to accept.

Second Soult government (May 1839 – February 1840)

After Molé's fall, Louis-Philippe immediately called upon Marshal Soult, who attempted, without success, to form a government including the three leaders of the coalition who had brought down Molé: Guizot, Thiers and Odilon Barrot. Confronted with the Doctrinaires' refusal, he then tried to form a centre-left cabinet, which also foundered upon Thiers' intransigence concerning Spanish affairs. These successive setbacks forced the king to postpone to 4 April 1839 the opening of the parliamentary session. Thiers also refused to be associated with the duc de Broglie and Guizot. The king then attempted to keep him at bay by offering him an embassy, which provoked the outcries of Thiers' friends. Finally, Louis-Philippe resigned himself to composing, on 31 March 1839, a transitional and neutral government.

The parliamentary session opened on 4 April in a quasi-insurrectionary atmosphere. A large mob had gathered around the Palais-Bourbon, seat of the Assembly, singing La Marseillaise and rioting. The left-wing press accused the government of provocations. Thiers supported Odilon Barrot as President of the Chamber, but his attitude during the negotiations for the formation of a new cabinet had disappointed some of his friends. A part of the center-left thus decided to present Hippolyte Passy against Barrot. The latter won with 227 votes against 193, supported by the ministerial deputies and the Doctrinaires. This vote demonstrated that the coalition had imploded, and that a right-wing majority could be formed to oppose any left-wing initiative.

Despite this, the negotiations for the formation of a new cabinet still were unsuccessful, with Thiers making his friends promise to request his authorization before accepting any governmental function. The situation seemed at an impasse, when on 12 May 1839, the Société des saisons, a secret Republican society, headed by Martin Bernard, Armand Barbès and Auguste Blanqui, organized an insurrection in the rue Saint-Denis and the rue Saint-Martin in Paris. The League of the Just, founded in 1836, participated in this uprising.[15] However, not only was it a failure, and the conspirators arrested, but this allowed Louis-Philippe to form a new government on the same day, presided over by Marshal Soult who had assured him of his loyal support.

At the end of May, the vote on the secret funds gave a large majority to the new government, which also had the budget passed without any problems. The parliamentary recess was decreed on 6 August 1838, and the new session opened on 23 December, during which the Chamber voted a rather favorable address to the government by 212 votes to 43. Soult's cabinet, however, fell on 20 February 1839, 226 deputies having voted against proposed dowry of the duc de Nemours (only 200 votes for), who was to marry Victoire de Saxe-Cobourg-Kohary. Proudhon noted in a letter the thoughtlessness of the bourgeoisie, who supported the monarchy without supporting its consequences[16]

The second Thiers cabinet (March – October 1840)

Soult's fall compelled the king to call on the main left-wing figure, Adolphe Thiers. Guizot, one of the only remaining right-wing alternatives, had just been named ambassador to London and left France. Thiers' aim was to definitively establish parliamentary government, with a "king who reigns but does not rule", and a cabinet drawn from the parliamentary majority and answerable to it. Henceforth, he clearly opposed Louis-Philippe's concept of government.

Thiers formed his government on 1 March 1840. He first pretended to offer the presidency of the Council to the duc de Broglie, and then Soult, before accepting it and taking Foreign Affairs at the same time. His cabinet was composed of fairly young politicians (47 years old on average), Thiers himself being only 42.

Relations with the king were immediately difficult. Louis-Philippe embarrassed Thiers by suggesting that he nominate his friend Horace Sébastiani as Marshal, which would expose him to the same criticisms he had previously suffered over political favoritism and the abuse of governmental power. Thiers thus decided to postpone Sébastiani's advancement.

Thiers obtained an easy majority during the debate on the secret funds in March 1840 (246 votes to 160). Although he was classified as centre-left, Thiers' second government was highly conservative, and dedicated to the protection of the interests of the bourgeoisie. Although he had the deputies pass the vote on government bond conversion, which was a left-wing proposal, he was sure that it would be rejected by the Peers, which is what happened. On 16 May 1840, Thiers harshly rejected universal suffrage and social reforms after a speech by the Radical François Arago, who had linked the ideas of electoral reform and social reform.[17] Arago was attempting to unite the left-wing by tying together universal suffrage claims and Socialist claims, which had appeared in the 1840s, concerning the "right of work" (droit au travail). He believed that electoral reform to establish universal suffrage should precede the social reform, which he considered very urgent.

On 15 June 1838, Thiers obtained the postponement of a proposal made by the conservative deputy of Versailles, Ovide de Rémilly who, equipping himself with an old demand of the Left, sought to outlaw the nomination of deputies to salaried public offices during their elective mandate. As Thiers had previously supported this proposition, he was acutely criticized by the Left.

Since the end of August 1838, social problems related to the economic crisis which started in 1839 causedstrike actions and riots in the textile, clothing and construction sectors. On 7 September 1839, the cabinet-makers of the faubourg Saint-Antoine started to put up barricades. Thiers responded by sending out the National Guard and invoking the laws prohibiting public meetings.

Thiers also renewed the Banque de France's privilege until 1867 on such advantageous terms that the Bank had a commemorative gold medal cast. Several laws also established steamship lines, operated by companies operating state-subsidised concessions. Other laws granted credits or guarantees to railway companies in difficulties.

Return of Napoleon's ashes

While Thiers favored the conservative bourgeoisie, he also made sure to satisfy the Left's thirst for glory. On 12 May 1840, the Minister of the Interior, Charles de Rémusat, announced to the deputies that the king had decided that the remains of Napoléon would be transferred to the Invalides. With the British government's agreement, the prince de Joinville sailed to Saint Helena on the frigate La Belle Poule to retrieve them.

This announcement immediately struck a chord with public opinion, which was swept along with patriotic fervor. Thiers saw in this act the successful completion of the rehabilitation of the Revolution and of the Empire, which he had attempted in his Histoire de la Révolution française and his Histoire du Consulat et de l'Empire, while Louis-Philippe, who was reluctant, aimed at capturing for himself a touch of the imperial glory, just as he had appropriated the legitimist monarchy's glory in the Château de Versailles. The prince Louis-Napoléon decided to seize the opportunity to land in Boulogne-sur-Mer on 6 August 1840, with the aim of rallying the 42nd infantry regiment (42e régiment de ligne) along with some accomplices including one of Napoléon's comrades in Saint Helena, the General de Montholon. Although Montholon was in reality a double agent used by the French government to spy, in London, on Louis-Napoléon, Montholon deceived Thiers by letting him think that the operation would take place in Metz. However, Bonaparte's operation was a complete failure, and he was detained with his men in the Fort of Ham, Picardy.

Their trial took place before the Chamber of Peers from 28 September 1840 to 6 October 1840, to general indifference. The public's attention was concentrated on the trial of Marie Lafarge, before the Cour d'assises of Tulle, the defendant being accused of having poisoned her husband. Defended by the famous Legitimist lawyer Pierre-Antoine Berryer, Bonaparte was sentenced to life detention, by 152 votes (against 160 abstentions, out of a total of 312 Peers). "We do not kill insane people, all right! but we do confine them,[18] declared the Journal des débats, in this period of intense discussions concerning parricides, mental disease and reform of the penal code.[19]

Colonization of Algeria

The conquest of Algeria, initiated in the last days of the Bourbon Restoration, was now confronted by Abd-el-Kader's raids, punishing Marshal Valée and the duc d'Orléans's expedition to the Portes de Fer in autumn 1839, which had violated the terms of the 1837 Treaty of Tafna between General Bugeaud and Abd-el-Kader. Thiers pushed in favor of colonising of the interior of the country, up to the edges of the desert. He convinced the king, who saw in Algeria an ideal theater for his son to cover the House of Orléans with glory, and persuaded him to send General Bugeaud as first governor general of Algeria. Bugeaud, who would lead harsh repression against the natives, was officially nominated on 29 December 1840, a few days after Thiers' fall.

Middle Eastern affairs, a pretext for Thiers' fall

Thiers supported Mehemet Ali, the pasha of Egypt, in his ambition to constitute a vast Arabian Empire from Egypt to Syria. He tried to intercede in order to have him sign an agreement with the Ottoman Empire, unbeknownst to the four other European powers (Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia). However, informed of these negotiations, the British Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lord Palmerston, quickly negotiated a treaty between the four powers to sort out the "Eastern Question". When revealed, the London Convention of 15 July 1840 provoked an explosion of patriotic fury: France had been ousted from a zone where it traditionally exercised its influence, while Prussia, which had no interest in it, was associated with the treaty. Although Louis-Philippe pretended to join the general protestations, he knew that he could take advantage of the situation to get rid of Thiers.

The latter pandered tp patriotic feelings by decreeing, on 29 July 1840, a partial mobilization, and by starting, on 13 September 1840, the works on the fortifications of Paris. But France remained passive when, on 2 October 1840, the British navy shelled Beirut. Mehemet Ali was then immediately dismissed as viceroy by the Sultan.

Following long negotiations between the king and Thiers, a compromise was found on 7 October 1840: France would renounce its support for Mehemet Ali's pretensions in Syria but would declare to the European powers that Egypt should remain at all costs independent. Britain thereafter recognized Mehmet Ali's hereditary rule on Egypt: France had obtained a return to the situation of 1832. Despite this, the rupture between Thiers and Louis-Philippe was now definitive. On 29 October 1840, when Charles de Rémusat presented to the Council of Ministers the draft of the speech of the throne, prepared by Hippolyte Passy, Louis-Philippe found it too aggressive. After a short discussion, Thiers and his associates collectively presented their resignations to the king, who accepted them. On the following day, Louis-Philippe sent for Marshal Soult and Guizot so they could return to Paris as soon as possible.

The Guizot government (1840–1848)