On the Origin of Species

The title page of the 1859 edition of On the Origin of Species[1] | |

| Author | Charles Darwin |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland |

| Language | English |

| Subject |

Natural selection Evolutionary biology |

| Genre | Science, biology |

| Published | 24 November 1859[2] (John Murray) |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 502 |

| OCLC | 352242 |

| Preceded by | On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection |

| Followed by | Fertilisation of Orchids |

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

|

History of evolutionary theory |

|

Fields and applications

|

|

On the Origin of Species (or more completely, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life),[3] published on 24 November 1859, is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin which is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology. Darwin's book introduced the scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of generations through a process of natural selection. It presented a body of evidence that the diversity of life arose by common descent through a branching pattern of evolution. Darwin included evidence that he had gathered on the Beagle expedition in the 1830s and his subsequent findings from research, correspondence, and experimentation.[4]

Various evolutionary ideas had already been proposed to explain new findings in biology. There was growing support for such ideas among dissident anatomists and the general public, but during the first half of the 19th century the English scientific establishment was closely tied to the Church of England, while science was part of natural theology. Ideas about the transmutation of species were controversial as they conflicted with the beliefs that species were unchanging parts of a designed hierarchy and that humans were unique, unrelated to other animals. The political and theological implications were intensely debated, but transmutation was not accepted by the scientific mainstream.

The book was written for non-specialist readers and attracted widespread interest upon its publication. As Darwin was an eminent scientist, his findings were taken seriously and the evidence he presented generated scientific, philosophical, and religious discussion. The debate over the book contributed to the campaign by T. H. Huxley and his fellow members of the X Club to secularise science by promoting scientific naturalism. Within two decades there was widespread scientific agreement that evolution, with a branching pattern of common descent, had occurred, but scientists were slow to give natural selection the significance that Darwin thought appropriate. During "the eclipse of Darwinism" from the 1880s to the 1930s, various other mechanisms of evolution were given more credit. With the development of the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s, Darwin's concept of evolutionary adaptation through natural selection became central to modern evolutionary theory, and it has now become the unifying concept of the life sciences.

Summary of Darwin's theory

Darwin's theory of evolution is based on key facts and the inferences drawn from them, which biologist Ernst Mayr summarised as follows:[5]

- Every species is fertile enough that if all offspring survived to reproduce, the population would grow (fact).

- Despite periodic fluctuations, populations remain roughly the same size (fact).

- Resources such as food are limited and are relatively stable over time (fact).

- A struggle for survival ensues (inference).

- Individuals in a population vary significantly from one another (fact).

- Much of this variation is heritable (fact).

- Individuals less suited to the environment are less likely to survive and less likely to reproduce; individuals more suited to the environment are more likely to survive and more likely to reproduce and leave their heritable traits to future generations, which produces the process of natural selection (fact).

- This slowly effected process results in populations changing to adapt to their environments, and ultimately, these variations accumulate over time to form new species (inference).

Background

Developments before Darwin's theory

In later editions of the book, Darwin traced evolutionary ideas as far back as Aristotle;[6] the text he cites is a summary by Aristotle of the ideas of the earlier Greek philosopher Empedocles.[7] Early Christian Church Fathers and Medieval European scholars interpreted the Genesis creation narrative allegorically rather than as a literal historical account;[8] organisms were described by their mythological and heraldic significance as well as by their physical form. Nature was widely believed to be unstable and capricious, with monstrous births from union between species, and spontaneous generation of life.[9]

The Protestant Reformation inspired a literal interpretation of the Bible, with concepts of creation that conflicted with the findings of an emerging science seeking explanations congruent with the mechanical philosophy of René Descartes and the empiricism of the Baconian method. After the turmoil of the English Civil War, the Royal Society wanted to show that science did not threaten religious and political stability. John Ray developed an influential natural theology of rational order; in his taxonomy, species were static and fixed, their adaptation and complexity designed by God, and varieties showed minor differences caused by local conditions. In God's benevolent design, carnivores caused mercifully swift death, but the suffering caused by parasitism was a puzzling problem. The biological classification introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1735 also viewed species as fixed according to the divine plan. In 1766, Georges Buffon suggested that some similar species, such as horses and asses, or lions, tigers, and leopards, might be varieties descended from a common ancestor. The Ussher chronology of the 1650s had calculated creation at 4004 BC, but by the 1780s geologists assumed a much older world. Wernerians thought strata were deposits from shrinking seas, but James Hutton proposed a self-maintaining infinite cycle, anticipating uniformitarianism.[10]

Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus Darwin outlined a hypothesis of transmutation of species in the 1790s, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck published a more developed theory in 1809. Both envisaged that spontaneous generation produced simple forms of life that progressively developed greater complexity, adapting to the environment by inheriting changes in adults caused by use or disuse. This process was later called Lamarckism. Lamarck thought there was an inherent progressive tendency driving organisms continuously towards greater complexity, in parallel but separate lineages with no extinction.[11] Geoffroy contended that embryonic development recapitulated transformations of organisms in past eras when the environment acted on embryos, and that animal structures were determined by a constant plan as demonstrated by homologies. Georges Cuvier strongly disputed such ideas, holding that unrelated, fixed species showed similarities that reflected a design for functional needs.[12] His palæontological work in the 1790s had established the reality of extinction, which he explained by local catastrophes, followed by repopulation of the affected areas by other species.[13]

In Britain, William Paley's Natural Theology saw adaptation as evidence of beneficial "design" by the Creator acting through natural laws. All naturalists in the two English universities (Oxford and Cambridge) were Church of England clergymen, and science became a search for these laws.[14] Geologists adapted catastrophism to show repeated worldwide annihilation and creation of new fixed species adapted to a changed environment, initially identifying the most recent catastrophe as the biblical flood.[15] Some anatomists such as Robert Grant were influenced by Lamarck and Geoffroy, but most naturalists regarded their ideas of transmutation as a threat to divinely appointed social order.[16]

Inception of Darwin's theory

Darwin went to Edinburgh University in 1825 to study medicine. In his second year he neglected his medical studies for natural history and spent four months assisting Robert Grant's research into marine invertebrates. Grant revealed his enthusiasm for the transmutation of species, but Darwin rejected it.[17] Starting in 1827, at Cambridge University, Darwin learnt science as natural theology from botanist John Stevens Henslow, and read Paley, John Herschel and Alexander von Humboldt. Filled with zeal for science, he studied catastrophist geology with Adam Sedgwick.[18][19]

In December 1831, he joined the Beagle expedition as a gentleman naturalist and geologist. He read Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology and from the first stop ashore, at St. Jago, found Lyell's uniformitarianism a key to the geological history of landscapes. Darwin discovered fossils resembling huge armadillos, and noted the geographical distribution of modern species in hope of finding their "centre of creation".[20] The three Fuegian missionaries the expedition returned to Tierra del Fuego were friendly and civilised, yet to Darwin their relatives on the island seemed "miserable, degraded savages",[21] and he no longer saw an unbridgeable gap between humans and animals.[22] As the Beagle neared England in 1836, he noted that species might not be fixed.[23][24]

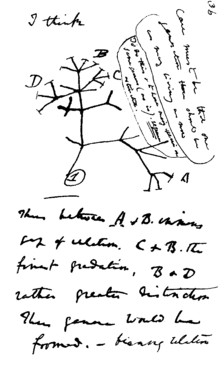

Richard Owen showed that fossils of extinct species Darwin found in South America were allied to living species on the same continent. In March 1837, ornithologist John Gould announced that Darwin's rhea was a separate species from the previously described rhea (though their territories overlapped), that mockingbirds collected on the Galápagos Islands represented three separate species each unique to a particular island, and that several distinct birds from those islands were all classified as finches.[25] Darwin began speculating, in a series of notebooks, on the possibility that "one species does change into another" to explain these findings, and around July sketched a genealogical branching of a single evolutionary tree, discarding Lamarck's independent lineages progressing to higher forms.[26][27][28] Unconventionally, Darwin asked questions of fancy pigeon and animal breeders as well as established scientists. At the zoo he had his first sight of an ape, and was profoundly impressed by how human the orangutan seemed.[29]

In late September 1838, he started reading Thomas Malthus's An Essay on the Principle of Population with its statistical argument that human populations, if unrestrained, breed beyond their means and struggle to survive. Darwin related this to the struggle for existence among wildlife and botanist de Candolle's "warring of the species" in plants; he immediately envisioned "a force like a hundred thousand wedges" pushing well-adapted variations into "gaps in the economy of nature", so that the survivors would pass on their form and abilities, and unfavourable variations would be destroyed.[30][31][32] By December 1838, he had noted a similarity between the act of breeders selecting traits and a Malthusian Nature selecting among variants thrown up by "chance" so that "every part of newly acquired structure is fully practical and perfected".[33]

Darwin now had the framework of his theory of natural selection "by which to work",[34] but he was fully occupied with his career as a geologist and held off writing a sketch of his theory until his book on The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs was completed in May 1842.[35][36]

Further development

Darwin continued to research and extensively revise his theory while focusing on his main work of publishing the scientific results of the Beagle voyage.[35] He tentatively wrote of his ideas to Lyell in January 1842;[37] then in June he roughed out a 35-page "Pencil Sketch" of his theory.[38] Darwin began correspondence about his theorising with the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker in January 1844, and by July had rounded out his "sketch" into a 230-page "Essay", to be expanded with his research results and published if he died prematurely.[39]

In November 1844, the anonymously published popular science book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, written by Scottish journalist Robert Chambers, widened public interest in the concept of transmutation of species. Vestiges used evidence from the fossil record and embryology to support the claim that living things had progressed from the simple to the more complex over time. But it proposed a linear progression rather than the branching common descent theory behind Darwin's work in progress, and it ignored adaptation. Darwin read it soon after publication, and scorned its amateurish geology and zoology,[40] but he carefully reviewed his own arguments after leading scientists, including Adam Sedgwick, attacked its morality and scientific errors.[41] Vestiges had significant influence on public opinion, and the intense debate helped to pave the way for the acceptance of the more scientifically sophisticated Origin by moving evolutionary speculation into the mainstream. While few naturalists were willing to consider transmutation, Herbert Spencer became an active proponent of Lamarckism and progressive development in the 1850s.[42]

Hooker was persuaded to take away a copy of the "Essay" in January 1847, and eventually sent a page of notes giving Darwin much needed feedback. Reminded of his lack of expertise in taxonomy, Darwin began an eight-year study of barnacles, becoming the leading expert on their classification. Using his theory, he discovered homologies showing that slightly changed body parts served different functions to meet new conditions, and he found an intermediate stage in the evolution of distinct sexes.[43][44]

Darwin's barnacle studies convinced him that variation arose constantly and not just in response to changed circumstances. In 1854, he completed the last part of his Beagle-related writing and began working full-time on evolution. His thinking changed from the view that species formed in isolated populations only, as on islands, to an emphasis on speciation without isolation; that is, he saw increasing specialisation within large stable populations as continuously exploiting new ecological niches. He conducted empirical research focusing on difficulties with his theory. He studied the developmental and anatomical differences between different breeds of many domestic animals, became actively involved in fancy pigeon breeding, and experimented (with the help of his son Francis) on ways that plant seeds and animals might disperse across oceans to colonise distant islands. By 1856, his theory was much more sophisticated, with a mass of supporting evidence.[43][45]

Publication

Time taken to publish

Darwin had his basic theory of natural selection "by which to work" by December 1838, yet almost twenty years later, in June 1858, Darwin was still not ready to publish his theory. It was long thought that Darwin avoided or delayed making his ideas public for personal reasons. Reasons suggested have included fear of religious persecution or social disgrace if his views were revealed, and concern about upsetting his clergymen naturalist friends or his pious wife Emma. Charles Darwin's illness caused repeated delays. His paper on Glen Roy had proved embarrassingly wrong, and he may have wanted to be sure he was correct. David Quammen has suggested all these factors may have contributed, and notes Darwin's large output of books and busy family life during that time.[46]

A more recent study by science historian John van Wyhe has determined that the idea that Darwin delayed publication only dates back to the 1940s, and Darwin's contemporaries thought the time he took was reasonable. Darwin always finished one book before starting another. While he was researching, he told many people about his interest in transmutation without causing outrage. He firmly intended to publish, but it was not until September 1854 that he could work on it full-time. His estimation that writing his "big book" would take five years proved optimistic.[47]

Events leading to publication: "big book" manuscript

An 1855 paper on the "introduction" of species, written by Alfred Russel Wallace, claimed that patterns in the geographical distribution of living and fossil species could be explained if every new species always came into existence near an already existing, closely related species.[48] Charles Lyell recognised the implications of Wallace's paper and its possible connection to Darwin's work, although Darwin did not, and in a letter written on 1–2 May 1856 Lyell urged Darwin to publish his theory to establish priority. Darwin was torn between the desire to set out a full and convincing account and the pressure to quickly produce a short paper. He met Lyell, and in correspondence with Joseph Dalton Hooker affirmed that he did not want to expose his ideas to review by an editor as would have been required to publish in an academic journal. He began a "sketch" account on 14 May 1856, and by July had decided to produce a full technical treatise on species as his "big book" on Natural Selection. His theory including the principle of divergence was complete by 5 September 1857 when he sent Asa Gray a brief but detailed abstract of his ideas.[49][50]

Joint publication of papers by Wallace and Darwin

Darwin was hard at work on the manuscript for his "big book" on Natural Selection, when on 18 June 1858 he received a parcel from Wallace, who stayed on the Maluku Islands (Ternate and Gilolo). It enclosed twenty pages describing an evolutionary mechanism, a response to Darwin's recent encouragement, with a request to send it on to Lyell if Darwin thought it worthwhile. The mechanism was similar to Darwin's own theory.[49] Darwin wrote to Lyell that "your words have come true with a vengeance, ... forestalled" and he would "of course, at once write and offer to send [it] to any journal" that Wallace chose, adding that "all my originality, whatever it may amount to, will be smashed".[51] Lyell and Hooker agreed that a joint publication putting together Wallace's pages with extracts from Darwin's 1844 Essay and his 1857 letter to Gray should be presented at the Linnean Society, and on 1 July 1858, the papers entitled On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection, by Wallace and Darwin respectively, were read out but drew little reaction. While Darwin considered Wallace's idea to be identical to his concept of natural selection, historians have pointed out differences. Darwin described natural selection as being analogous to the artificial selection practised by animal breeders, and emphasised competition between individuals; Wallace drew no comparison to selective breeding, and focused on ecological pressures that kept different varieties adapted to local conditions.[52][53][54] Some historians have suggested that Wallace was actually discussing group selection rather than selection acting on individual variation.[55]

Abstract of Species book

Soon after the meeting, Darwin decided to write "an abstract of my whole work" in the form of one or more papers to be published by the Linnean Society, but was concerned about "how it can be made scientific for a Journal, without giving facts, which would be impossible." He asked Hooker how many pages would be available, but "If the Referees were to reject it as not strictly scientific I would, perhaps publish it as pamphet."[56][57] He began his "abstract of Species book" on 20 July 1858, while on holiday at Sandown,[58] and wrote parts of it from memory, while sending the manuscripts to his friends for checking.[59]

By early October, he began to "expect my abstract will run into a small volume, which will have to be published separately."[60] Over the same period, he continued to collect information and write large fully detailed sections of the manuscript for his "big book" on Species, Natural Selection.[56]

Murray as publisher; choice of title

By mid March 1859 Darwin's abstract had reached the stage where he was thinking of early publication; Lyell suggested the publisher John Murray, and met with him to find if he would be willing to publish. On 28 March Darwin wrote to Lyell asking about progress, and offering assurances "that my Book is not more un-orthodox, than the subject makes inevitable. That I do not discuss origin of man.— That I do not bring in any discussions about Genesis &c, & only give facts, & such conclusions from them, as seem to me fair." He enclosed a draft title sheet proposing An abstract of an Essay on the Origin of Species and Varieties Through natural selection, with the year shown as "1859".[61][62]

Murray's response was favourable, and a very pleased Darwin told Lyell on 30 March that he would "send shortly a large bundle of M.S. but unfortunately I cannot for a week, as the three first chapters are in three copyists’ hands". He bowed to Murray's objection to "abstract" in the title, though he felt it excused the lack of references, but wanted to keep "natural selection" which was "constantly used in all works on Breeding", and hoped "to retain it with Explanation, somewhat as thus",— Through Natural Selection or the preservation of favoured races.[62][63] On 31 March Darwin wrote to Murray in confirmation, and listed headings of the 12 chapters in progress: he had drafted all except "XII. Recapitulation & Conclusion".[64] Murray responded immediately with an agreement to publish the book on the same terms as he published Lyell, without even seeing the manuscript: he offered Darwin 2⁄3 of the profits.[65] Darwin promptly accepted with pleasure, insisting that Murray would be free to withdraw the offer if, having read the chapter manuscripts, he felt the book would not sell well.[66] (eventually Murray paid £180 to Darwin for the 1st edition and by Darwin's death in 1882 the book was in its 6th edition, earning Darwin nearly £3000.[67])

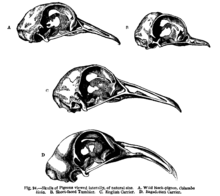

On 5 April, Darwin sent Murray the first three chapters, and a proposal for the book's title.[68] An early draft title page suggests On the Mutability of Species.[69] Murray cautiously asked Whitwell Elwin to review the chapters.[56] At Lyell's suggestion, Elwin recommended that, rather than "put forth the theory without the evidence", the book should focus on observations upon pigeons, briefly stating how these illustrated Darwin's general principles and preparing the way for the larger work expected shortly: "Every body is interested in pigeons."[70] Darwin responded that this was impractical: he had only the last chapter still to write.[71] In September the main title still included "An essay on the origin of species and varieties", but Darwin now proposed dropping "varieties".[72] With Murray's persuasion, the title was eventually agreed as the snappier On the Origin of Species, with the title page adding by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.[3]

Here and elsewhere in the book, Darwin used the biological term "races" interchangeably with "varieties",[73] meaning varieties within a species,[74] in a broad sense covering competing individuals or groups, whether of the same "race" or of different "races".[75] Thus, he discussed "the several races, for instance, of the cabbage" and "the hereditary varieties or races of our domestic animals and plants".[76] There are very few references to human races.[77] Darwin was not ready yet to tackle the topical disputes over slavery and European racial superiority, and the word "races" may have been intended to signify relevance to the moral debates of the time. In Difficulties for the theory he indicated that the principle of sexual selection could also apply to "the races of man", and his concluding remarks hinted that his theory would be relevant to human origins.[78][79]

Darwin's text accepted the doctrine of Peter Simon Pallas that domestic breeds had been hybridised from two or more wild species.[80] In October, Lyell asked if this could help to explain human racial differences.[81] Darwin replied that it was too close to the polygenism of Louis Agassiz: "The Races of Man offer great difficulty: I do not think doctrine of Pallas, or that of Agassiz that there are several species of man, helps us in the least".[82][83]

Publication and subsequent editions

On the Origin of Species was first published on Thursday 24 November 1859, priced at fifteen shillings with a first printing of 1250 copies.[84] The book had been offered to booksellers at Murray's autumn sale on Tuesday 22 November, and all available copies had been taken up immediately. In total, 1,250 copies were printed but after deducting presentation and review copies, and five for Stationers' Hall copyright, around 1,170 copies were available for sale.[2] Significantly, 500 were taken by Mudie's Library, ensuring that the book promptly reached a large number of subscribers to the library.[85] The second edition of 3,000 copies was quickly brought out on 7 January 1860,[86] and incorporated numerous corrections as well as a response to religious objections by the addition of a new epigraph on page ii, a quotation from Charles Kingsley, and the phrase "by the Creator" added to the closing sentence.[87] During Darwin's lifetime the book went through six editions, with cumulative changes and revisions to deal with counter-arguments raised. The third edition came out in 1861, with a number of sentences rewritten or added and an introductory appendix, An Historical Sketch of the Recent Progress of Opinion on the Origin of Species,[88] while the fourth in 1866 had further revisions. The fifth edition, published on 10 February 1869, incorporated more changes and for the first time included the phrase "survival of the fittest", which had been coined by the philosopher Herbert Spencer in his Principles of Biology (1864).[89]

In January 1871, George Jackson Mivart's On the Genesis of Species listed detailed arguments against natural selection, and claimed it included false metaphysics.[90] Darwin made extensive revisions to the sixth edition of the Origin (this was the first edition in which he used the word "evolution" which had commonly been associated with embryological development, though all editions concluded with the word "evolved"[91][92]), and added a new chapter VII, Miscellaneous objections, to address Mivart's arguments.[2][93]

The sixth edition was published by Murray on 19 February 1872 as The Origin of Species, with "On" dropped from the title. Darwin had told Murray of working men in Lancashire clubbing together to buy the 5th edition at fifteen shillings and wanted it made more widely available; the price was halved to 7s 6d by printing in a smaller font. It includes a glossary compiled by W.S. Dallas. Book sales increased from 60 to 250 per month.[3][93]

Publication outside Great Britain

.jpg)

In the United States, botanist Asa Gray, an American colleague of Darwin, negotiated with a Boston publisher for publication of an authorised American version, but learnt that two New York publishing firms were already planning to exploit the absence of international copyright to print Origin.[94] Darwin was delighted by the popularity of the book, and asked Gray to keep any profits.[95] Gray managed to negotiate a 5% royalty with Appleton's of New York,[96] who got their edition out in mid January 1860, and the other two withdrew. In a May letter, Darwin mentioned a print run of 2,500 copies, but it is not clear if this referred to the first printing only as there were four that year.[2][97]

The book was widely translated in Darwin's lifetime, but problems arose with translating concepts and metaphors, and some translations were biased by the translator's own agenda.[98] Darwin distributed presentation copies in France and Germany, hoping that suitable applicants would come forward, as translators were expected to make their own arrangements with a local publisher. He welcomed the distinguished elderly naturalist and geologist Heinrich Georg Bronn, but the German translation published in 1860 imposed Bronn's own ideas, adding controversial themes that Darwin had deliberately omitted. Bronn translated "favoured races" as "perfected races", and added essays on issues including the origin of life, as well as a final chapter on religious implications partly inspired by Bronn's adherence to Naturphilosophie.[99] In 1862, Bronn produced a second edition based on the third English edition and Darwin's suggested additions, but then died of a heart attack.[100] Darwin corresponded closely with Julius Victor Carus, who published an improved translation in 1867.[101] Darwin's attempts to find a translator in France fell through, and the translation by Clémence Royer published in 1862 added an introduction praising Darwin's ideas as an alternative to religious revelation and promoting ideas anticipating social Darwinism and eugenics, as well as numerous explanatory notes giving her own answers to doubts that Darwin expressed. Darwin corresponded with Royer about a second edition published in 1866 and a third in 1870, but he had difficulty getting her to remove her notes and was troubled by these editions.[100][102] He remained unsatisfied until a translation by Edmond Barbier was published in 1876.[2] A Dutch translation by Tiberius Cornelis Winkler was published in 1860.[103] By 1864, additional translations had appeared in Italian and Russian.[98] In Darwin's lifetime, Origin was published in Swedish in 1871,[104] Danish in 1872, Polish in 1873, Hungarian in 1873–1874, Spanish in 1877 and Serbian in 1878. By 1977, it had appeared in an additional 18 languages.[105]

Content

Title pages and introduction

Page ii contains quotations by William Whewell and Francis Bacon on the theology of natural laws,[106] harmonising science and religion in accordance with Isaac Newton's belief in a rational God who established a law-abiding cosmos.[107] In the second edition, Darwin added an epigraph from Joseph Butler affirming that God could work through scientific laws as much as through miracles, in a nod to the religious concerns of his oldest friends.[87] The Introduction establishes Darwin's credentials as a naturalist and author,[108] then refers to John Herschel's letter suggesting that the origin of species "would be found to be a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process":[109]

WHEN on board HMS Beagle, as naturalist, I was much struck with certain facts in the distribution of the inhabitants of South America, and in the geological relations of the present to the past inhabitants of that continent. These facts seemed to me to throw some light on the origin of species—that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers.[110]

Darwin refers specifically to the distribution of the species rheas, and to that of the Galápagos tortoises and mockingbirds. He mentions his years of work on his theory, and the arrival of Wallace at the same conclusion, which led him to "publish this Abstract" of his incomplete work. He outlines his ideas, and sets out the essence of his theory:

As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.[111]

Starting with the third edition, Darwin prefaced the introduction with a sketch of the historical development of evolutionary ideas.[112] In that sketch he acknowledged that Patrick Matthew had, unknown to Wallace or himself, anticipated the concept of natural selection in an appendix to a book published in 1831;[113] in the fourth edition he mentioned that William Charles Wells had done so as early as 1813.[114]

Variation under domestication and under nature

Chapter I covers animal husbandry and plant breeding, going back to ancient Egypt. Darwin discusses contemporary opinions on the origins of different breeds under cultivation to argue that many have been produced from common ancestors by selective breeding.[115] As an illustration of artificial selection, he describes fancy pigeon breeding,[116] noting that "[t]he diversity of the breeds is something astonishing", yet all were descended from one species of rock pigeon.[117] Darwin saw two distinct kinds of variation: (1) rare abrupt changes he called "sports" or "monstrosities" (example: Ancon sheep with short legs), and (2) ubiquitous small differences (example: slightly shorter or longer bill of pigeons).[118] Both types of hereditary changes can be used by breeders. However, for Darwin the small changes were most important in evolution.

In Chapter II, Darwin specifies that the distinction between species and varieties is arbitrary, with experts disagreeing and changing their decisions when new forms were found. He concludes that "a well-marked variety may be justly called an incipient species" and that "species are only strongly marked and permanent varieties".[119] He argues for the ubiquity of variation in nature.[120] Historians have noted that naturalists had long been aware that the individuals of a species differed from one another, but had generally considered such variations to be limited and unimportant deviations from the archetype of each species, that archetype being a fixed ideal in the mind of God. Darwin and Wallace made variation among individuals of the same species central to understanding the natural world.[116]

Struggle for existence, natural selection, and divergence

In Chapter III, Darwin asks how varieties "which I have called incipient species" become distinct species, and in answer introduces the key concept he calls "natural selection";[121] in the fifth edition he adds, "But the expression often used by Mr. Herbert Spencer, of the Survival of the Fittest, is more accurate, and is sometimes equally convenient."[122]

Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring ... I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection, in order to mark its relation to man's power of selection.[121]

He notes that both A. P. de Candolle and Charles Lyell had stated that all organisms are exposed to severe competition. Darwin emphasizes that he used the phrase "struggle for existence" in "a large and metaphorical sense, including dependence of one being on another"; he gives examples ranging from plants struggling against drought to plants competing for birds to eat their fruit and disseminate their seeds. He describes the struggle resulting from population growth: "It is the doctrine of Malthus applied with manifold force to the whole animal and vegetable kingdoms." He discusses checks to such increase including complex ecological interdependencies, and notes that competition is most severe between closely related forms "which fill nearly the same place in the economy of nature".[123]

Chapter IV details natural selection under the "infinitely complex and close-fitting ... mutual relations of all organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life".[124] Darwin takes as an example a country where a change in conditions led to extinction of some species, immigration of others and, where suitable variations occurred, descendants of some species became adapted to new conditions. He remarks that the artificial selection practised by animal breeders frequently produced sharp divergence in character between breeds, and suggests that natural selection might do the same, saying:

But how, it may be asked, can any analogous principle apply in nature? I believe it can and does apply most efficiently, from the simple circumstance that the more diversified the descendants from any one species become in structure, constitution, and habits, by so much will they be better enabled to seize on many and widely diversified places in the polity of nature, and so be enabled to increase in numbers.[125]

Historians have remarked that here Darwin anticipated the modern concept of an ecological niche.[126] He did not suggest that every favourable variation must be selected, nor that the favoured animals were better or higher, but merely more adapted to their surroundings.

Darwin proposes sexual selection, driven by competition between males for mates, to explain sexually dimorphic features such as lion manes, deer antlers, peacock tails, bird songs, and the bright plumage of some male birds.[127] He analysed sexual selection more fully in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). Natural selection was expected to work very slowly in forming new species, but given the effectiveness of artificial selection, he could "see no limit to the amount of change, to the beauty and infinite complexity of the coadaptations between all organic beings, one with another and with their physical conditions of life, which may be effected in the long course of time by nature's power of selection". Using a tree diagram and calculations, he indicates the "divergence of character" from original species into new species and genera. He describes branches falling off as extinction occurred, while new branches formed in "the great Tree of life ... with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications".[128]

Variation and heredity

In Darwin's time there was no agreed-upon model of heredity;[129] in Chapter I Darwin admitted, "The laws governing inheritance are quite unknown."[130] He accepted a version of the inheritance of acquired characteristics (which after Darwin's death came to be called Lamarckism), and Chapter V discusses what he called the effects of use and disuse; he wrote that he thought "there can be little doubt that use in our domestic animals strengthens and enlarges certain parts, and disuse diminishes them; and that such modifications are inherited", and that this also applied in nature.[131] Darwin stated that some changes that were commonly attributed to use and disuse, such as the loss of functional wings in some island dwelling insects, might be produced by natural selection. In later editions of Origin, Darwin expanded the role attributed to the inheritance of acquired characteristics. Darwin also admitted ignorance of the source of inheritable variations, but speculated they might be produced by environmental factors.[132][133] However, one thing was clear: whatever the exact nature and causes of new variations, Darwin knew from observation and experiment that breeders were able to select such variations and produce huge differences in many generations of selection.[118] The observation that selection works in domestic animals is not destroyed by lack of understanding of the underlying hereditary mechanism.

Breeding of animals and plants showed related varieties varying in similar ways, or tending to revert to an ancestral form, and similar patterns of variation in distinct species were explained by Darwin as demonstrating common descent. He recounted how Lord Morton's mare apparently demonstrated telegony, offspring inheriting characteristics of a previous mate of the female parent, and accepted this process as increasing the variation available for natural selection.[134][135]

More detail was given in Darwin's 1868 book on The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, which tried to explain heredity through his hypothesis of pangenesis. Although Darwin had privately questioned blending inheritance, he struggled with the theoretical difficulty that novel individual variations would tend to blend into a population. However, inherited variation could be seen,[136] and Darwin's concept of selection working on a population with a range of small variations was workable.[137] It was not until the modern evolutionary synthesis in the 1930s and 1940s that a model of heredity became completely integrated with a model of variation.[138] This modern evolutionary synthesis had been dubbed Neo Darwinian Evolution because it encompasses Charles Darwin's theories of evolution with Gregor Mendel's theories of genetic inheritance.[139]

Difficulties for the theory

Chapter VI begins by saying the next three chapters will address possible objections to the theory, the first being that often no intermediate forms between closely related species are found, though the theory implies such forms must have existed. As Darwin noted, "Firstly, why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion, instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?"[140] Darwin attributed this to the competition between different forms, combined with the small number of individuals of intermediate forms, often leading to extinction of such forms.[141] This difficulty can be referred to as the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in habitat space.

Another difficulty, related to the first one, is the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in time. Darwin commented that by the theory of natural selection "innumerable transitional forms must have existed," and wondered "why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?" [142] (for further discussion of these difficulties, see Speciation#Darwin's dilemma: Why do species exist? and Bernstein et al.[143] and Michod[144])

The chapter then deals with whether natural selection could produce complex specialised structures, and the behaviours to use them, when it would be difficult to imagine how intermediate forms could be functional. Darwin said:

Secondly, is it possible that an animal having, for instance, the structure and habits of a bat, could have been formed by the modification of some animal with wholly different habits? Can we believe that natural selection could produce, on the one hand, organs of trifling importance, such as the tail of a giraffe, which serves as a fly-flapper, and, on the other hand, organs of such wonderful structure, as the eye, of which we hardly as yet fully understand the inimitable perfection?[145]

His answer was that in many cases animals exist with intermediate structures that are functional. He presented flying squirrels, and flying lemurs as examples of how bats might have evolved from non-flying ancestors.[146] He discussed various simple eyes found in invertebrates, starting with nothing more than an optic nerve coated with pigment, as examples of how the vertebrate eye could have evolved. Darwin concludes: "If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case."[147]

In a section on "organs of little apparent importance", Darwin discusses the difficulty of explaining various seemingly trivial traits with no evident adaptive function, and outlines some possibilities such as correlation with useful features. He accepts that we "are profoundly ignorant of the causes producing slight and unimportant variations" which distinguish domesticated breeds of animals,[148] and human races. He suggests that sexual selection might explain these variations:[149][150]

I might have adduced for this same purpose the differences between the races of man, which are so strongly marked; I may add that some little light can apparently be thrown on the origin of these differences, chiefly through sexual selection of a particular kind, but without here entering on copious details my reasoning would appear frivolous.[79]

Chapter VII (of the first edition) addresses the evolution of instincts. His examples included two he had investigated experimentally: slave-making ants and the construction of hexagonal cells by honey bees. Darwin noted that some species of slave-making ants were more dependent on slaves than others, and he observed that many ant species will collect and store the pupae of other species as food. He thought it reasonable that species with an extreme dependency on slave workers had evolved in incremental steps. He suggested that bees that make hexagonal cells evolved in steps from bees that made round cells, under pressure from natural selection to economise wax. Darwin concluded:

Finally, it may not be a logical deduction, but to my imagination it is far more satisfactory to look at such instincts as the young cuckoo ejecting its foster-brothers, —ants making slaves, —the larvæ of ichneumonidæ feeding within the live bodies of caterpillars, —not as specially endowed or created instincts, but as small consequences of one general law, leading to the advancement of all organic beings, namely, multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die.[151]

Chapter VIII addresses the idea that species had special characteristics that prevented hybrids from being fertile in order to preserve separately created species. Darwin said that, far from being constant, the difficulty in producing hybrids of related species, and the viability and fertility of the hybrids, varied greatly, especially among plants. Sometimes what were widely considered to be separate species produced fertile hybrid offspring freely, and in other cases what were considered to be mere varieties of the same species could only be crossed with difficulty. Darwin concluded: "Finally, then, the facts briefly given in this chapter do not seem to me opposed to, but even rather to support the view, that there is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties."[152]

In the sixth edition Darwin inserted a new chapter VII (renumbering the subsequent chapters) to respond to criticisms of earlier editions, including the objection that many features of organisms were not adaptive and could not have been produced by natural selection. He said some such features could have been by-products of adaptive changes to other features, and that often features seemed non-adaptive because their function was unknown, as shown by his book on Fertilisation of Orchids that explained how their elaborate structures facilitated pollination by insects. Much of the chapter responds to George Jackson Mivart's criticisms, including his claim that features such as baleen filters in whales, flatfish with both eyes on one side and the camouflage of stick insects could not have evolved through natural selection because intermediate stages would not have been adaptive. Darwin proposed scenarios for the incremental evolution of each feature.[153]

Geologic record

Chapter IX deals with the fact that the geologic record appears to show forms of life suddenly arising, without the innumerable transitional fossils expected from gradual changes. Darwin borrowed Charles Lyell's argument in Principles of Geology that the record is extremely imperfect as fossilisation is a very rare occurrence, spread over vast periods of time; since few areas had been geologically explored, there could only be fragmentary knowledge of geological formations, and fossil collections were very poor. Evolved local varieties which migrated into a wider area would seem to be the sudden appearance of a new species. Darwin did not expect to be able to reconstruct evolutionary history, but continuing discoveries gave him well founded hope that new finds would occasionally reveal transitional forms.[154][155] To show that there had been enough time for natural selection to work slowly, he cited the example of The Weald as discussed in Principles of Geology together with other observations from Hugh Miller, James Smith of Jordanhill and Andrew Ramsay. Combining this with an estimate of recent rates of sedimentation and erosion, Darwin calculated that erosion of The Weald had taken around 300 million years.[156] The initial appearance of entire groups of well developed organisms in the oldest fossil-bearing layers, now known as the Cambrian explosion, posed a problem. Darwin had no doubt that earlier seas had swarmed with living creatures, but stated that he had no satisfactory explanation for the lack of fossils.[157] Fossil evidence of pre-Cambrian life has since been found, extending the history of life back for billions of years.[158]

Chapter X examines whether patterns in the fossil record are better explained by common descent and branching evolution through natural selection, than by the individual creation of fixed species. Darwin expected species to change slowly, but not at the same rate – some organisms such as Lingula were unchanged since the earliest fossils. The pace of natural selection would depend on variability and change in the environment.[159] This distanced his theory from Lamarckian laws of inevitable progress.[154] It has been argued that this anticipated the punctuated equilibrium hypothesis,[155][160] but other scholars have preferred to emphasise Darwin's commitment to gradualism.[161] He cited Richard Owen's findings that the earliest members of a class were a few simple and generalised species with characteristics intermediate between modern forms, and were followed by increasingly diverse and specialised forms, matching the branching of common descent from an ancestor.[154] Patterns of extinction matched his theory, with related groups of species having a continued existence until extinction, then not reappearing. Recently extinct species were more similar to living species than those from earlier eras, and as he had seen in South America, and William Clift had shown in Australia, fossils from recent geological periods resembled species still living in the same area.[159]

Geographic distribution

Chapter XI deals with evidence from biogeography, starting with the observation that differences in flora and fauna from separate regions cannot be explained by environmental differences alone; South America, Africa, and Australia all have regions with similar climates at similar latitudes, but those regions have very different plants and animals. The species found in one area of a continent are more closely allied with species found in other regions of that same continent than to species found on other continents. Darwin noted that barriers to migration played an important role in the differences between the species of different regions. The coastal sea life of the Atlantic and Pacific sides of Central America had almost no species in common even though the Isthmus of Panama was only a few miles wide. His explanation was a combination of migration and descent with modification. He went on to say: "On this principle of inheritance with modification, we can understand how it is that sections of genera, whole genera, and even families are confined to the same areas, as is so commonly and notoriously the case."[162] Darwin explained how a volcanic island formed a few hundred miles from a continent might be colonised by a few species from that continent. These species would become modified over time, but would still be related to species found on the continent, and Darwin observed that this was a common pattern. Darwin discussed ways that species could be dispersed across oceans to colonise islands, many of which he had investigated experimentally.[163]

Chapter XII continues the discussion of biogeography. After a brief discussion of freshwater species, it returns to oceanic islands and their peculiarities; for example on some islands roles played by mammals on continents were played by other animals such as flightless birds or reptiles. The summary of both chapters says:

... I think all the grand leading facts of geographical distribution are explicable on the theory of migration (generally of the more dominant forms of life), together with subsequent modification and the multiplication of new forms. We can thus understand the high importance of barriers, whether of land or water, which separate our several zoological and botanical provinces. We can thus understand the localisation of sub-genera, genera, and families; and how it is that under different latitudes, for instance in South America, the inhabitants of the plains and mountains, of the forests, marshes, and deserts, are in so mysterious a manner linked together by affinity, and are likewise linked to the extinct beings which formerly inhabited the same continent ... On these same principles, we can understand, as I have endeavoured to show, why oceanic islands should have few inhabitants, but of these a great number should be endemic or peculiar; ...[164]

Classification, morphology, embryology, rudimentary organs

Chapter XIII starts by observing that classification depends on species being grouped together in a Taxonomy, a multilevel system of groups and sub groups based on varying degrees of resemblance. After discussing classification issues, Darwin concludes:

All the foregoing rules and aids and difficulties in classification are explained, if I do not greatly deceive myself, on the view that the natural system is founded on descent with modification; that the characters which naturalists consider as showing true affinity between any two or more species, are those which have been inherited from a common parent, and, in so far, all true classification is genealogical; that community of descent is the hidden bond which naturalists have been unconsciously seeking, ...[165]

Darwin discusses morphology, including the importance of homologous structures. He says, "What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern, and should include the same bones, in the same relative positions?" This made no sense under doctrines of independent creation of species, as even Richard Owen had admitted, but the "explanation is manifest on the theory of the natural selection of successive slight modifications" showing common descent.[166] He notes that animals of the same class often have extremely similar embryos. Darwin discusses rudimentary organs, such as the wings of flightless birds and the rudiments of pelvis and leg bones found in some snakes. He remarks that some rudimentary organs, such as teeth in baleen whales, are found only in embryonic stages.[167] These factors also supported his theory of descent with modification.[30]

Concluding remarks

The final chapter "Recapitulation and Conclusion" reviews points from earlier chapters, and Darwin concludes by hoping that his theory might produce revolutionary changes in many fields of natural history.[168] He suggests that psychology will be put on a new foundation and implies the relevance of his theory to the first appearance of humanity with the sentence that "Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history."[30][169] Darwin ends with a passage that became well known and much quoted:

It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us ... Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.[170]

As discussed under religious attitudes, Darwin added the phrase "by the Creator" from the 1860 second edition onwards, so that the ultimate sentence began "There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one".[171]

Structure and style

Nature and structure of Darwin's argument

Darwin's aims were twofold: to show that species had not been separately created, and to show that natural selection had been the chief agent of change.[172] He knew that his readers were already familiar with the concept of transmutation of species from Vestiges, and his introduction ridicules that work as failing to provide a viable mechanism.[173] Therefore, the first four chapters lay out his case that selection in nature, caused by the struggle for existence, is analogous to the selection of variations under domestication, and that the accumulation of adaptive variations provides a scientifically testable mechanism for evolutionary speciation.[174][175]

Later chapters provide evidence that evolution has occurred, supporting the idea of branching, adaptive evolution without directly proving that selection is the mechanism. Darwin presents supporting facts drawn from many disciplines, showing that his theory could explain a myriad of observations from many fields of natural history that were inexplicable under the alternate concept that species had been individually created.[175][176][177] The structure of Darwin's argument showed the influence of John Herschel, whose philosophy of science maintained that a mechanism could be called a vera causa (true cause) if three things could be demonstrated: its existence in nature, its ability to produce the effects of interest, and its ability to explain a wide range of observations.[178]

Literary style

The Examiner review of 3 December 1859 commented, "Much of Mr. Darwin's volume is what ordinary readers would call 'tough reading;' that is, writing which to comprehend requires concentrated attention and some preparation for the task. All, however, is by no means of this description, and many parts of the book abound in information, easy to comprehend and both instructive and entertaining."[173][179]

While the book was readable enough to sell, its dryness ensured that it was seen as aimed at specialist scientists and could not be dismissed as mere journalism or imaginative fiction. Unlike the still-popular Vestiges, it avoided the narrative style of the historical novel and cosmological speculation, though the closing sentence clearly hinted at cosmic progression. Darwin had long been immersed in the literary forms and practices of specialist science, and made effective use of his skills in structuring arguments.[173] David Quammen has described the book as written in everyday language for a wide audience, but noted that Darwin's literary style was uneven: in some places he used convoluted sentences that are difficult to read, while in other places his writing was beautiful. Quammen advised that later editions were weakened by Darwin making concessions and adding details to address his critics, and recommended the first edition.[180] James T. Costa said that because the book was an abstract produced in haste in response to Wallace's essay, it was more approachable than the big book on natural selection Darwin had been working on, which would have been encumbered by scholarly footnotes and much more technical detail. He added that some parts of Origin are dense, but other parts are almost lyrical, and the case studies and observations are presented in a narrative style unusual in serious scientific books, which broadened its audience.[181]

Reception

.jpg)

The book aroused international interest[183] and a widespread debate, with no sharp line between scientific issues and ideological, social and religious implications.[184] Much of the initial reaction was hostile, in a large part because very few reviewers actually understood his theory,[185] but Darwin had to be taken seriously as a prominent and respected name in science. There was much less controversy than had greeted the 1844 publication Vestiges of Creation, which had been rejected by scientists,[183] but had influenced a wide public readership into believing that nature and human society were governed by natural laws.[30] The Origin of Species as a book of wide general interest became associated with ideas of social reform. Its proponents made full use of a surge in the publication of review journals, and it was given more popular attention than almost any other scientific work, though it failed to match the continuing sales of Vestiges.[186] Darwin's book legitimised scientific discussion of evolutionary mechanisms, and the newly coined term Darwinism was used to cover the whole range of evolutionism, not just his own ideas. By the mid-1870s, evolutionism was triumphant.[184]

While Darwin had been somewhat coy about human origins, not identifying any explicit conclusion on the matter in his book, he had dropped enough hints about human's animal ancestry for the inference to be made,[187][188] and the first review claimed it made a creed of the "men from monkeys" idea from Vestiges.[189][190] Human evolution became central to the debate and was strongly argued by Huxley who featured it in his popular "working-men's lectures". Darwin did not publish his own views on this until 1871.[191][192]

The naturalism of natural selection conflicted with presumptions of purpose in nature and while this could be reconciled by theistic evolution, other mechanisms implying more progress or purpose were more acceptable. Herbert Spencer had already incorporated Lamarckism into his popular philosophy of progressive free market human society. He popularised the terms evolution and survival of the fittest, and many thought Spencer was central to evolutionary thinking.[193]

Impact on the scientific community

Scientific readers were already aware of arguments that species changed through processes that were subject to laws of nature, but the transmutational ideas of Lamarck and the vague "law of development" of Vestiges had not found scientific favour. Darwin presented natural selection as a scientifically testable mechanism while accepting that other mechanisms such as inheritance of acquired characters were possible. His strategy established that evolution through natural laws was worthy of scientific study, and by 1875, most scientists accepted that evolution occurred but few thought natural selection was significant. Darwin's scientific method was also disputed, with his proponents favouring the empiricism of John Stuart Mill's A System of Logic, while opponents held to the idealist school of William Whewell's Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, in which investigation could begin with the intuitive truth that species were fixed objects created by design.[194] Early support for Darwin's ideas came from the findings of field naturalists studying biogeography and ecology, including Joseph Dalton Hooker in 1860, and Asa Gray in 1862. Henry Walter Bates presented research in 1861 that explained insect mimicry using natural selection. Alfred Russel Wallace discussed evidence from his Malay archipelago research, including an 1864 paper with an evolutionary explanation for the Wallace line.[195]

Evolution had less obvious applications to anatomy and morphology, and at first had little impact on the research of the anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley.[197] Despite this, Huxley strongly supported Darwin on evolution; though he called for experiments to show whether natural selection could form new species, and questioned if Darwin's gradualism was sufficient without sudden leaps to cause speciation. Huxley wanted science to be secular, without religious interference, and his article in the April 1860 Westminster Review promoted scientific naturalism over natural theology,[198][199] praising Darwin for "extending the domination of Science over regions of thought into which she has, as yet, hardly penetrated" and coining the term "Darwinism" as part of his efforts to secularise and professionalise science.[200] Huxley gained influence, and initiated the X Club, which used the journal Nature to promote evolution and naturalism, shaping much of late Victorian science. Later, the German morphologist Ernst Haeckel would convince Huxley that comparative anatomy and palaeontology could be used to reconstruct evolutionary genealogies.[197][201]

The leading naturalist in Britain was the anatomist Richard Owen, an idealist who had shifted to the view in the 1850s that the history of life was the gradual unfolding of a divine plan.[202] Owen's review of the Origin in the April 1860 Edinburgh Review bitterly attacked Huxley, Hooker and Darwin, but also signalled acceptance of a kind of evolution as a teleological plan in a continuous "ordained becoming", with new species appearing by natural birth. Others that rejected natural selection, but supported "creation by birth", included the Duke of Argyll who explained beauty in plumage by design.[203][204] Since 1858, Huxley had emphasised anatomical similarities between apes and humans, contesting Owen's view that humans were a separate sub-class. Their disagreement over human origins came to the fore at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting featuring the legendary 1860 Oxford evolution debate.[205][206] In two years of acrimonious public dispute that Charles Kingsley satirised as the "Great Hippocampus Question" and parodied in The Water-Babies as the "great hippopotamus test", Huxley showed that Owen was incorrect in asserting that ape brains lacked a structure present in human brains.[207] Others, including Charles Lyell and Alfred Russel Wallace, thought that humans shared a common ancestor with apes, but higher mental faculties could not have evolved through a purely material process. Darwin published his own explanation in the Descent of Man (1871).[208]

Impact outside Great Britain

.jpg)

Evolutionary ideas, although not natural selection, were accepted by German biologists accustomed to ideas of homology in morphology from Goethe's Metamorphosis of Plants and from their long tradition of comparative anatomy. Bronn's alterations in his German translation added to the misgivings of conservatives, but enthused political radicals. Ernst Haeckel was particularly ardent, aiming to synthesise Darwin's ideas with those of Lamarck and Goethe while still reflecting the spirit of Naturphilosophie.[99][210] Their ambitious programme to reconstruct the evolutionary history of life was joined by Huxley and supported by discoveries in palaeontology. Haeckel used embryology extensively in his recapitulation theory, which embodied a progressive, almost linear model of evolution. Darwin was cautious about such histories, and had already noted that von Baer's laws of embryology supported his idea of complex branching.[209]

Asa Gray promoted and defended Origin against those American naturalists with an idealist approach, notably Louis Agassiz who viewed every species as a distinct fixed unit in the mind of the Creator, classifying as species what others considered merely varieties.[211] Edward Drinker Cope and Alpheus Hyatt reconciled this view with evolutionism in a form of neo-Lamarckism involving recapitulation theory.[210]

French-speaking naturalists in several countries showed appreciation of the much modified French translation by Clémence Royer, but Darwin's ideas had little impact in France, where any scientists supporting evolutionary ideas opted for a form of Lamarckism.[102] The intelligentsia in Russia had accepted the general phenomenon of evolution for several years before Darwin had published his theory, and scientists were quick to take it into account, although the Malthusian aspects were felt to be relatively unimportant. The political economy of struggle was criticised as a British stereotype by Karl Marx and by Leo Tolstoy, who had the character Levin in his novel Anna Karenina voice sharp criticism of the morality of Darwin's views.[98]

Challenges to natural selection

Orange labels: known ice ages.

Also see: Human timeline and Nature timeline

There were serious scientific objections to the process of natural selection as the key mechanism of evolution, including Karl von Nägeli's insistence that a trivial characteristic with no adaptive advantage could not be developed by selection. Darwin conceded that these could be linked to adaptive characteristics. His estimate that the age of the Earth allowed gradual evolution was disputed by William Thomson (later awarded the title Lord Kelvin), who calculated that it had cooled in less than 100 million years. Darwin accepted blending inheritance, but Fleeming Jenkin calculated that as it mixed traits, natural selection could not accumulate useful traits. Darwin tried to meet these objections in the 5th edition. Mivart supported directed evolution, and compiled scientific and religious objections to natural selection. In response, Darwin made considerable changes to the sixth edition. The problems of the age of the Earth and heredity were only resolved in the 20th century.[90][212]

By the mid-1870s, most scientists accepted evolution, but relegated natural selection to a minor role as they believed evolution was purposeful and progressive. The range of evolutionary theories during "the eclipse of Darwinism" included forms of "saltationism" in which new species were thought to arise through "jumps" rather than gradual adaptation, forms of orthogenesis claiming that species had an inherent tendency to change in a particular direction, and forms of neo-Lamarckism in which inheritance of acquired characteristics led to progress. The minority view of August Weismann, that natural selection was the only mechanism, was called neo-Darwinism. It was thought that the rediscovery of Mendelian inheritance invalidated Darwin's views.[213][214]

Impact on economic and political debates

While some, like Spencer, used analogy from natural selection as an argument against government intervention in the economy to benefit the poor, others, including Alfred Russel Wallace, argued that action was needed to correct social and economic inequities to level the playing field before natural selection could improve humanity further. Some political commentaries, including Walter Bagehot's Physics and Politics (1872), attempted to extend the idea of natural selection to competition between nations and between human races. Such ideas were incorporated into what was already an ongoing effort by some working in anthropology to provide scientific evidence for the superiority of Caucasians over non white races and justify European imperialism. Historians write that most such political and economic commentators had only a superficial understanding of Darwin's scientific theory, and were as strongly influenced by other concepts about social progress and evolution, such as the Lamarckian ideas of Spencer and Haeckel, as they were by Darwin's work. Darwin objected to his ideas being used to justify military aggression and unethical business practices as he believed morality was part of fitness in humans, and he opposed polygenism, the idea that human races were fundamentally distinct and did not share a recent common ancestry.[215]

Religious attitudes

The book produced a wide range of religious responses at a time of changing ideas and increasing secularisation. The issues raised were complex and there was a large middle ground. Developments in geology meant that there was little opposition based on a literal reading of Genesis,[216] but defence of the argument from design and natural theology was central to debates over the book in the English-speaking world.[217][218]

Natural theology was not a unified doctrine, and while some such as Louis Agassiz were strongly opposed to the ideas in the book, others sought a reconciliation in which evolution was seen as purposeful.[216] In the Church of England, some liberal clergymen interpreted natural selection as an instrument of God's design, with the cleric Charles Kingsley seeing it as "just as noble a conception of Deity".[220][221] In the second edition of January 1860, Darwin quoted Kingsley as "a celebrated cleric", and added the phrase "by the Creator" to the closing sentence, which from then on read "life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one".[171] While some commentators have taken this as a concession to religion that Darwin later regretted,[87] Darwin's view at the time was of God creating life through the laws of nature,[222][223] and even in the first edition there are several references to "creation".[224]

Baden Powell praised "Mr Darwin's masterly volume [supporting] the grand principle of the self-evolving powers of nature".[225] In America, Asa Gray argued that evolution is the secondary effect, or modus operandi, of the first cause, design,[226] and published a pamphlet defending the book in terms of theistic evolution, Natural Selection is not inconsistent with Natural Theology.[220][227][228] Theistic evolution became a popular compromise, and St. George Jackson Mivart was among those accepting evolution but attacking Darwin's naturalistic mechanism. Eventually it was realised that supernatural intervention could not be a scientific explanation, and naturalistic mechanisms such as neo-Lamarckism were favoured over natural selection as being more compatible with purpose.[216]

Even though the book did not explicitly spell out Darwin's beliefs about human origins, it had dropped a number of hints about human's animal ancestry[188] and quickly became central to the debate, as mental and moral qualities were seen as spiritual aspects of the immaterial soul, and it was believed that animals did not have spiritual qualities. This conflict could be reconciled by supposing there was some supernatural intervention on the path leading to humans, or viewing evolution as a purposeful and progressive ascent to mankind's position at the head of nature.[216] While many conservative theologians accepted evolution, Charles Hodge argued in his 1874 critique "What is Darwinism?" that "Darwinism", defined narrowly as including rejection of design, was atheism though he accepted that Asa Gray did not reject design.[229][230] Asa Gray responded that this charge misrepresented Darwin's text.[231] By the early 20th century, four noted authors of The Fundamentals were explicitly open to the possibility that God created through evolution,[232] but fundamentalism inspired the American creation–evolution controversy that began in the 1920s. Some conservative Roman Catholic writers and influential Jesuits opposed evolution in the late 19th and early 20th century, but other Catholic writers, starting with Mivart, pointed out that early Church Fathers had not interpreted Genesis literally in this area.[233] The Vatican stated its official position in a 1950 papal encyclical, which held that evolution was not inconsistent with Catholic teaching.[234][235]

Modern influence

Various alternative evolutionary mechanisms favoured during "the eclipse of Darwinism" became untenable as more was learned about inheritance and mutation. The full significance of natural selection was at last accepted in the 1930s and 1940s as part of the modern evolutionary synthesis. During that synthesis biologists and statisticians, including R. A. Fisher, Sewall Wright and J.B.S. Haldane, merged Darwinian selection with a statistical understanding of Mendelian genetics.[214]

Modern evolutionary theory continues to develop. Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection, with its tree-like model of branching common descent, has become the unifying theory of the life sciences. The theory explains the diversity of living organisms and their adaptation to the environment. It makes sense of the geologic record, biogeography, parallels in embryonic development, biological homologies, vestigiality, cladistics, phylogenetics and other fields, with unrivalled explanatory power; it has also become essential to applied sciences such as medicine and agriculture.[236][237] Despite the scientific consensus, a religion-based political controversy has developed over how evolution is taught in schools, especially in the United States.[238]

Interest in Darwin's writings continues, and scholars have generated an extensive literature, the Darwin Industry, about his life and work. The text of Origin itself has been subject to much analysis including a variorum, detailing the changes made in every edition, first published in 1959,[239] and a concordance, an exhaustive external index published in 1981.[240] Worldwide commemorations of the 150th anniversary of the publication of On the Origin of Species and the bicentenary of Darwin's birth were scheduled for 2009.[241] They celebrated the ideas which "over the last 150 years have revolutionised our understanding of nature and our place within it".[242]

In a survey conducted by a group of academic booksellers, publishers and librarians in advance of Academic Book Week in the United Kingdom, On the Origin of Species was voted the most influential academic book ever written.[243] It was hailed as "the supreme demonstration of why academic books matter" and "a book which has changed the way we think about everything".[244]

See also

- On the Origin of Species – full text at Wikisource of the first edition, 1859

- The Origin of Species – full text at Wikisource of the 6th edition, 1872

- Charles Darwin bibliography

- History of biology

- History of evolutionary thought

- Modern evolutionary synthesis

- The Complete Works of Charles Darwin Online

- The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, published in 1871; his second major book on evolutionary theory.

- Transmutation of species

Notes

- ↑ Darwin 1859, p. iii

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freeman 1977