Organogels

An organogel is a class of gel composed of a liquid organic phase within a three-dimensional, cross-linked network. Organogel networks can form in two ways. The first is classic gel network formation via polymerization. This mechanism converts a precursor solution of monomers with various reactive sites into polymeric chains that grow into a single covalently-linked network. At a critical concentration (the gel point), the polymeric network becomes large enough so that on the macroscopic scale, the solution starts to exhibit gel-like physical properties: an extensive continuous solid network, no steady-state flow, and solid-like rheological properties.[1] However, organogels that are “low molecular weight gelators” can also be designed to form gels via self-assembly. Secondary forces, such as van der Waals or hydrogen bonding, cause monomers to cluster into a non-covalently bonded network that retains organic solvent, and as the network grows, it exhibits gel-like physical properties.[2] Both gelation mechanisms lead to gels characterized as organogels.

Gelation mechanism greatly influences the typical organogel properties. Since precursors with multiple functional groups polymerize into networks of covalent C-C bonds (on average 85 kcal/mol), networks formed by self-assembly, which relies on secondary forces (generally less than 10 kcal/mol), are less stable.[3],[4] Theorists also have difficulties predicting characteristic gelation parameters, such as gel point and gelation time, with a single and simple equation. Gel point, the transition point from a polymer solution to gel, is a function of the extent of reaction or the fraction of functional groups reacted. Gelation time is the time interval between the onset of reaction– by heating, addition of catalyst into a liquid system, etc.– and gel point. Kinetic and statistical mathematical theories have had moderate success in predicting gelation parameters; a simple, accurate, and widely applicable theory has not yet been developed.

This article will first discuss the details of organogels formation and the variables of the characteristic gelation parameters as they relate to organogels. Then, various methods used to characterize organogels will be explained. Finally, we will review the use of organogels in various industries.

Organogel formulation

The formulation of an accurate theory of gel formation that correctly predicts gelation parameters (such as time, rate, and structure) of a broad range of materials is highly sought after for both commercial and intellectual reasons. As noted earlier, researchers often judge gel theories based upon their ability to accurately predict gel points. The kinetic and statistical methods model gel formation with different mathematical approaches. As of 2014 most researchers used statistical methods, as the equations derived thereby are less cumbersome and contain variables to which specific physical meanings can be attached, thus aiding in the analysis of gel formation theory.[5] Below, we present the classical Flory-Stockmayer (FS) statistical theory for gel formation. This theory, despite its simplicity, has found widespread use. This is due in large part to small increases in accuracy due provided by the use of more complicated methods, and to its being a general model which can be applied to many gelation systems. Other gel formation theories cased on different chemical approximations have also been derived. However, the FS model has better simplicity, wide applicability, and accuracy, and remains the most used.

The kinetic approach

The kinetic (or coagulation) approach preserves the integrity of any and all structures created during network formation. Thus, an infinite set of differential rate equations (one for each possible structure, of which there essentially infinite) must be created in order to treat gel systems kinetically. Consequently, exact solutions for kinetic theories can be obtained for only the most basic systems.[6]

However, numerical answers to kinetic systems can be given via Monte Carlo methods. In general, kinetic treatments of gelation result in large, unwieldy, and dense sets of equations that give answers not discernibly better than those given by the statistical approach. A major drawback of the kinetic approach is that it treats the gel as essentially one giant, rigid molecule, and cannot actively simulate characteristic structures of gels such as elastic and dangling chains.[6] Kinetic models have mostly fallen out of use given how clumsy the equations become in everyday use. Interested readers however, are directed to the following papers for further reading on a specific kinetic model.[7],[8],[9]

The statistical approach

The statistical approach views the phase change from liquid to gel as a uniform process throughout the fluid. That is, polymerization reactions are occurring all throughout the solution, with each reaction having an equal chance of occurring. Statistical theories try to determine the fraction of the total possible bonds that need to be made before an infinite polymer network can appear. The classic statistical theory first developed by Flory rested on two critical assumptions.[10],[11]

- No intramolecular reactions occur. That is, no cyclic molecules form during polymerization lead-ing up to gelation.

- Every reactive unit has the same reactivity regardless of other factors. For example, a reactive group A on a 20-mer (a polymer with 20 monomer units) has the same reactivity as another group A on a 2000-mer.

Using the above assumptions, let us examine a homopolymerization reaction starting from a single monomer with z-functional groups with a fraction p of all possible bonds already having been formed. The polymer we create follows the form of a Cayley tree or Bethe lattice – known from the field of statistical mechanics. The number of branches from each node is determined by the amount of functional groups, z, on our monomer. As we follow the tree’s branches we want there to always be at least one path that leads onwards, as this is the condition of an infinite network polymer. At each node, there are z-1 possible paths, since one functional group was used to create the node. The probability that at least one of the possible paths has been created is (z-1)p. Since we want an infinite network, we require on average that (z-1)p ≥ 1 to ensure an infinitely long path. Therefore, the FS model predicts the critical point (pc) to be:

Physically, pc is the fraction of all possible bonds that can be made. So a pc of ½ means that the first point in time that an infinite network will be able to exist will be when ½ of all possible bonds have been made by the monomers.

This equation is derived for the simple case of a self-reacting monomer with a single type of reacting group A. The Flory model was further refined by Stockmayer to include multifunctional monomers.[12] However, the same two assumptions were kept. Thus, the classical statistical gel theory has come to be known as the Flory-Stockmayer (FS). The FS model gives the following equations for a bifunctional polymer system, and can be generalized to branch units of any amount of functionality following the steps laid out by Stockmayer.[12]

Where pA and pB are the fraction of all possible A and B bonds respectively and r (which must be less than 1) is the ratio of reactive sites of A and B on each monomer. If the starting concentrations of A and B reactive sites are the same, then pApB can be condensed to pgel2 and values for the fraction of all bonds at which an infinite network will form can be found.

fA and fB are defined as above, where NAi are the number of moles of Ai containing fAi functional groups for each type of A functional molecule.

Factors affecting gelation

Typically, gels are synthesized via sol-gel processing, a wet-chemical technique involving a colloidal solution (sol) that acts as the precursor for an integrated network (gel). There are two possible mechanisms whereby organogels form depending on the physical intermolecular inter-actions, namely the fluid-filled fiber and the solid fiber mechanism.[13] The main difference is in the starting materials, i.e. surfactant in apolar solvent versus solid organogelator in apolar solvent. Surfactant or surfactant mixture forms reverse micelles when mixed with an apolar solvent. The fluid-fiber matrix forms when a polar solvent (e.g. water) is added to the reverse micelles to encourage the formation of tubular reverse micelle structures.[13] As more polar solvent is added, the reverse micelles elongate and entangle to form organogel. Gel formation via solid-fiber matrix, on the other hand, forms when the mixture of organogelators in apolar solvent is heated to give apolar solution of organogelator and then cooled down below the solubility limit of the organogelators.[14] The organogelators precipitate out as fibers, forming a 3-dimensional network which then immobilizes the apolar solvent to produce organogels.[13] Table 1 lists the type of organogelators and the properties of the organogels synthesized.

- Table 1. Types of Organogelators and the Characteristics of their Organogels

| Types of Organogelators | Properties of Organogelators | Properties of Organogel Synthesized |

|---|---|---|

| 4-tertbutyl-1-aryl cyclohecanols derivatives[15] | Solid at room temperature; low solubility in apolar solvent | Transparent or turbid depending on the type of apolar solvent |

| Polymeric (e.g. poly(ethylene glycol), polycarbonate, polyesters, and poly(alkylene))[16] | Low sol-gel processing temperature | Good gel strength |

| Gemini gelators (e.g. N-lauroyl-L-lysine ethyl ester) | High ability of immobilizing apolar solvents | - |

| Boc-Ala(1)-Aib(2)-ß-Ala(3)-OMe (synthetic tripeptide)[17] | Capable of self-assembling | Thermoreversible; transparent |

| Low molecular weight gelators (e.g. fatty acids and n-alkanes) | High ability of immobilizing apolar solvents at small concentration (< 2%)[18] | Good mechanical properties |

Gelation times vary depending on the organogelators and medium. One can promote or delay gelation by influencing the molecular self-assembly of organogelators in a system. Molecular self-assembly is a process by which molecules adopt a defined arrangement without guidance or management from an external source. The organogelators may undergo physical or chemical interactions so as to form self-assembled fibrous structures in which they become entangled with each other, resulting in the formation of a three-dimensional network structure.[13] It is believed that the self-assembly is governed by non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic forces, van der Waals forces, π-π interactions etc. Although molecular self-assembly is not fully understood so far, researchers have demonstrated by adjusting certain aspects of the system, one is able to promote or inhibit self-assembly in organogelator molecules.

- Factors affecting gelation include but are not limited to:

Organogelators can be divided into two groups based on whether or not they form hydrogen bonds.[13] Hydrogen bond forming organogelators include, amino acids/amides/urea moieties and carbohydrates whereas non-hydrogen bond forming organogelators (e.g. π-π stacking) include anthracene-, anthraquinone- and steroid-based molecules.[21] Solubility and/or solvent-molecule interactions play an important role in promoting organogelator self-assembly.[22] Hirst et al.[22] showed that the solubility of the gelators in media can be modified by tuning the peripheral protecting groups of the gelators, which in turn controls the gel point and the concentrations at which crosslinking takes place (See Table 2 for data). Gelators that have higher solubility in medium show less preference for crosslinking. These gelators (Figure 1) are less effective and require higher total concentrations to initiate the process. In addition, solvent-molecule interactions also modulate the level of self-assembly. This was shown by Hirst et al. in the NMR binding model as well as in SAXS/SANS results.[22] Garner et al.[15] explored the importance of organogelator structures using 4-tertbutyl-1-aryl cy-clohexanol derivatives showing that a phenyl group in an axial configuration induces gelation, unlike derivatives with the phenyl group in equatorial configuration.[15] Polymeric organogelators can induce gelation even at very low concentrations (less than 20 g/L) and the self-assembly capability could be customized by modifying the chemical structure of the polymer backbone.[23]

- Table 2. The solubility as a result of Z and Boc in different positions of the molecule.

Adapted from Hirst et al.[22] ΔHdiss, kJ mol−1 ΔSdiss, J mol−1 K−1 Solubility at 30 °C, mM 4-Boc 44.7 (1.5) 119 (5) 31 (5)b 2-εZ 101.3 (1.7) 286 (6) 3 (0.5)b 2-αZ 102.6 (4.3) 259 (12) 0.3 (0.1)b 4-Z 106.4 (3.5) 252 (10) 0.007 (0.017)c - aFigures in parentheses indicate associated error. Solvent was Toluene.

bCalculated directly from 1H-NMR measurements at 30°C.

cCalculated from extrapolation of van't Hoff plot.

By manipulating the solvent-molecule interactions, one can promote molecular self-assembly of the organogelator and therefore gelation. Although this is the traditionally used approach, it has limitations. There are still no reliable models that describe the gelation for all kinds of organogelators in all media. An alternate approach is to promote self-assembly by triggering changes in intermolecular interactions, i.e. cis-trans isomerization, hydrogen bonding, donor-acceptor π-π stacking interaction, electrostatic interactions etc. Matsumoto et al.[24] and Hirst et al.[25] have reported gelation using light-induced isomerization and by incorporating additives into the system to influence molecular packing, respectively.

Matsumoto et al.[24] used UV light to trigger trans–cis photoisomerization of fumaric amide units causing self-assembly or disassembly to a gel or the corresponding sol, respectively (See Figure 2). Hirst et al., on the other hand, introduced a two-component system, where inserting a second component into the system changed the gelator’s behavior.[25] This had effectively controlled the molecular self-assembly process.

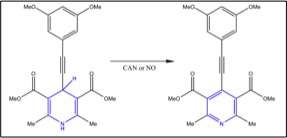

Chen et al.[19] designed a system that would undergo self-assembly by triggering changes in intermolecular interactions. They used an oxidation-induced planarization to trigger gelator self-assembly and gelation through donor-acceptor π-stacking interaction.[19] The interesting part is that both strong oxidants such as cerium(IV) ammonium nitrate and weak oxidants like nitric oxide, NO can induce gelation. Figure 3 shows the oxidation of dihydropyridine catalyzed/induced by NO. NO has been used as an analyte or biomarker for disease detection, and the discovery of NO’s role in analyte-triggered gelation system no doubt has opened new doors to the world of chemical sensing.

Characterization

Gels are characterized from two different perspectives. First, the physical structure of the gel is determined. This is followed by a characterization of the gel’s mechanical properties. The former generally affects the mechanical properties of gels.

Physical Characterization

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

This is a reliable technique for measuring the strength of the intermolecular interactions in gels. Gel network strength is proportional to the magnitude of enthalpy change (ΔH). A higher ΔH means a more tightly bonded network while a smaller enthalpy value means a network made of weaker bonds.[26]

Microscopy

There are numerous microscopy methods for defining gel structures which include SEM and TEM. Use of microscopic techniques can directly determine the physical parameters of the gel matrix. These include measurements of pore diameter, wall thickness and shape of the gel network.[27] Use of SEM can distinguish between gels that have a fibrous network as opposed to those that have a three-dimensional cross linked structure. It must be noted that microscopy techniques may not yield quantitatively accurate results. If a high vacuum is used during imaging, the liquid solvent can be removed from the gel matrix-inducing strain to the gel which leads to physical deformation. Use of an environmental SEM, which operates at higher pressures, can yield higher quality imaging.

Scattering

Two scattering techniques for indirectly measuring gel parameters are small angle X-ray scattering (SARS/SAXS) and small angle neutron scattering (SANS). SARS works exactly like X-ray scattering (XRD) except small angles (0.1-10.0 °) are used. The challenge with small angles is in separating the scattering pattern from the main beam. In SANS, the procedure is the same as SARS except that a neutron beam is used instead of an x-ray beam. One advantage of using a neutron beam as opposed to an x-ray beam is an increased signal to noise ratio. It also provides the ability for isotope labeling because the neutrons interact with the nuclei instead of the electrons. By analyzing the scattering pattern direct information about the size of the material can be obtained. Both SARS and SANS provide useful data on the atomic scale at 50-250 and 10-1000 Å respectively. These distances are perfectly suited for studying the physical parameters of gels.

Mechanical properties characterization

There are numerous methods to characterize the material properties of a gel. These are briefly summarized below.

Ball indentation

Hardness or stiffness of the gel is measured by placing a metal ball on top of the material and the hardness of the material depends on the amount of indentation caused by the ball.[28]

Atomic force microscopy

This technique utilizes a similar approach when compared to ball indentation only on a significantly small scale. The tip is lowered into the sample and a laser reflecting off the cantilever allows for precise measurements to be obtained.[28]

Uniaxial tensile testing

In this technique, the tensile strength of the gel is measured in one direction. The two important measurements to make include the force applied per unit area and the amount of elongation under a known applied force. This test provides information for how a gel will respond when an external force is applied.[28]

Viscoelasticity

Due to varying degrees of cross-linkage in a gel network, different gels display different visocoelastic properties. A material containing viscoelastic properties undergoes both viscous and elastic changes when a deformation occurs. Viscosity can be thought of as a time dependent process of a material deforming to a more relaxed state while elasticity is an instantaneous process. The viscoelastic properties of gels mean that they undergo time dependent structural changes in response to a physical deformation. Two techniques for measuring viscoelasticity are broadband viscoelastic spectroscopy (BVS) and resonant ultrasound spectroscopy (RUS). In both techniques, a damping mechanism is resolved with both differing frequency and time in order to determine the viscoelastic properties of the material.[28]

Applications

Organogels are useful in applications such as:

- drug delivery mediums for topical and oral pharmaceuticals[29]

- organic application mediums for cosmetics

- cleaning materials for art conservation[30]

- as delivery mediums and/or nutrients in nutraceuticals (vitamins and supplements),

- particles in personal care products (shampoo, conditioner, soap, toothpaste, etc.)[31]

- an crystalline fat alternative in food processing.[32]

An undesirable example of organogel formation is wax crystallization in petroleum.[33]

References

- ↑ Raghavan, S.R.; Douglas, J.F. Soft Matter. 2012, 8, 8539.

- ↑ Hirst, A.R.; Coates, I.A.; Boucheteau, T.R.; Miravet, J.F.; Escuder, B.; Castelletto, V.; Hamley, I.W.; Smith, D.K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9113-9121.

- ↑ Ege, S. N. Organic Chemistry Structure and Reactivity, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Mason, Ohio, 2009.

- ↑ Sinnokrot, M.O.; Sherrill, C.D. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006, 110, 10656.

- ↑ Pizzi, A.; Mittal, K. L. Handbook of Adhesive Technology, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, 200; Chap. 8.

- 1 2 Dusek, K.; Kuchanov, S. I.; Panyukov, S. V. In Polymer Networks ’91; Dusek, K and Kuchanov, S. I., eds.; VSP: Utrecht, 1992; Chap. 1, 4.

- ↑ Smoluchowski, M.V. Z. Phys. Chem. 1916, 92, 129-168.

- ↑ Souge, J. L. Analytic solutions to Smoluchowski’s coagulation equation: a combinatorial inter-pretation. J. Phys. A.: Math. Gen. 1985, 18, 3063.

- ↑ Mikos, A.; Takoudis, C.; Peppas, N. Kinetic modeling of copolymerization/crosslinking reac-tions. Macromolecules. 1986, 19, 2174-2182.

- ↑ Tobita, H.; Hamielec, A. A kinetic model for network formation in free radical polymerization. Makromol. Chem. Makromol. Symp. 1988, 20/21, 501-543.

- ↑ Plate, N. A.; Noah, O. V. A theoretical consideration of the kinetics and statistics of reactions of functional groups of macromolecules. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1979, 31, 133-73.

- 1 2 Bowman, C. N.; Peppas, N. A. A kinetic gelation method for the simulation of free-radical polymerizations. Chemical Engineering Science. 1992, 47, 1411-1419.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sahoo. S; Kumar, N. et al. Organogels: Properties and applications in drug delivery. Designed Monomers and Polymers. 2011, 14, 95-108.

- ↑ Koshima, H.; Matsusaka, W. Yu, H. Preparation and photoreaction of organogels based on ben-zophenone. J. Photochemistry and Photobiology A. 2003, 156, 83-90.

- 1 2 3 Garner, C.M., et al. Thermoreversible gelation of organic liquids by arylcyclohexanol deriva-tives : synthesis and characterization of the gels. Vol. 94. 1998, Cambridge, ROYAUME-UNI: Royal Society of Chemistry. 7.

- ↑ Suzuki, M., et al. Organogelation by Polymer Organogelators with a L-Lysine Deriva-tive: Formation of a Three-Dimensional Network Consisting of Supramolecular and Conventional Polymers. Chemistry - A European Journal. 2007, 13, 8193- 8200.

- ↑ Malik, S., et al. A synthetic tripeptide as organogelator: elucidation of gelation mecha-nism. J. Chem. Soc. 2002. 2, 1177 – 1186.

- ↑ Toro-Vazquez, J. et al. Thermal and Textural Properties of Organogels Developed by Candelilla Wax in Safflower Oil. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 2007, 84. 989-1000.

- 1 2 3 4 Chen, J.; McNeil, A. J. Analyte-triggered gelation: Initiating self-assembly via oxidation-induced planarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 16496-16497.

- ↑ Salehi et al. The effect of salinity and pH on gelation time of polymer gels using central compo-site design method. Presented at International Symposium of the Society of Core Analysts held in Austin, Texas, USA.

- ↑ Plourde, F. et al. First report on the efficacy of l-alanine-based in situ-forming implants for the long-term parenteral delivery of drugs. J. Controlled Release, 2005. 108, 433-441.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hirst et al. Low-Molecular-Weight Gelators: Elucidating the Principles of Gelation Based on Gelator Solubility and a Cooperative Self-Assembly Model. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9113–9121.

- ↑ Suzuki, M., and K. Hanabusa, Polymer organogelators that make supramolecular organo-gels through physical cross-linking and self-assembly. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 455 - 463.

- 1 2 3 Matsumoto, S.; Yamaguchi, S.; Ueno, S.; Komatsu, H.; Ikeda, M.; Ishizuka, K.; Iko, Y.; Tabata, K. V.; Aoki, H.; Ito, S.; Noji, H.; Hamachi, I. Photo Gel–Sol/Sol–Gel Transition and its Patterning of a Supramolecular Hydrogel as Stimuli-Responsive Biomaterials. J. Chem. Eur. 2008, 14, 3977–3986.

- 1 2 Hirst, A. R.; Smith, D. K. Two-Component Gel-Phase Materials—Highly Tunable Self-Assembling Systems. Chem.sEur. J. 2005, 11, 5496–5508.

- ↑ Watase, M.; Nakatani, Y.; Itagaki, H. J. Phys. Chem. B.. 1999, 103, 2366-2373

- ↑ Blank, Z.; Reimschuessel, A. C. Journal of Material Science. 1974, 9, 1815-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Gautreau, Z.; Griffen, J.; Peterson, T.; Thongpradit, P. Characterizing Viscoelastic Properties of Polyacrylamide Gels. Qualifying Report Project, Worcester Polytechnic Institute. 2006.

- ↑ Kumar, R; Katare, OP. Lecithin organogels as a potential phospholipid-structured system for top-ical drug delivery: A review. American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists PharmSciTech. 2005, 6, E298–E310.

- ↑ Carretti, E; Dei, L; Weiss, RG. Soft matter and art conservation. Rheoreversible gels and beyond. Soft Matter. 2005, 1, 17–22.

- ↑ Monica A. Hamer et al. 2005. Organogel particles. U.S. Patent 6,858,666, filed Mar 4, 2002, and issued Feb 22, 2005.

- ↑ Pernetti, M; van Malssen, K; Flöter, E; Bot A. Structuring of edible oil by alternatives to crystal-line fat. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science. 2007, 12, 221–231.

- ↑ Visintin, RFG; Lapasin, R; Vignati, E; D'Antona, P; Lockhart TP. Rheological behavior and structural interpretation of waxy crude oil gels. Langmuir. 2005, 21, 6240–6249.